Introduction: Can You Tell What’s Real?

At the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, a video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announcing the “surrender of the Ukrainian army” was widely circulated on social platforms. The video looks real: the background, tone, and facial movements are all “official.” Hackers even planted the fake video live on Ukrainian state television.

But here’s the thing — it was the result of AI Deepfakes, and it was quickly proven to be fake. Zelensky later recorded a video response: “Ukraine will not surrender.”

It’s not just fake news; it’s “fake reality.” We’re living in a digital world where it’s hard to tell what’s real from what’s fake, and Deepfakes is spreading rapidly across social platforms, not only changing what we see, but also influencing our perception of reality. Fake news is no longer just political rumors or gossip; it is becoming smarter, more widespread, and more “truth-like” under the influence of Deepfakes.

1. How AI Produces a New Wave of Fake Content?

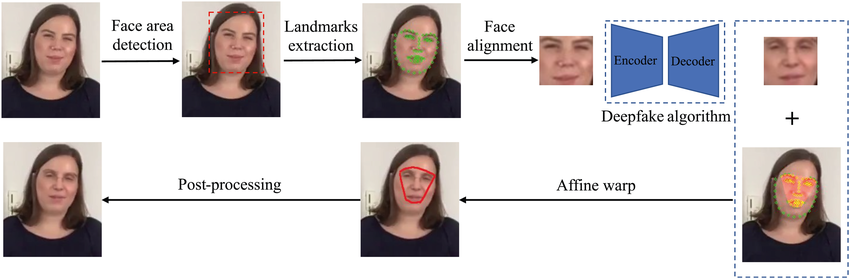

What is Deepfakes? Deepfakes, a portmanteau of deep learning and forgery, can perfectly “transplant” one person’s face, voice, and even movements into another person’s body or context (Kalpokas & Kalpokiene, 2022). In other words, Deepfakes can create fake video or audio that “looks like someone said something or did something.”

According to the Sumsub Research 2023, there has been a substantial 10x rise in the number of deepfakes identified worldwide across all sectors from 2022 to 2023, with significant regional variances: 1740% deepfake growth in North America, 780% in Europe (inc. the U.K.), 1530% in Asia Pacific, 450% in the Middle East and Africa, and 410% in Latin America (Fortune Business Insights, 2023).

This technology was once the exclusive domain of researchers and programmers, but now it has entered the public and even can be used in mobile apps with one click, and the threshold for fraud is extremely low. You may think that making a face-changing video requires high-end technology, but the reality is that at present, only an APP, such as FakeYou, Midjourney or ElevenLabs, uploads a voice or image and then generate a copy with ChatGPT, and it can generate a “fake” video in a few minutes.

Why does Deepfakes arise? First, from the point of view of the false propagator, the economic interest is driven using fake to make profits. Secondly, from the user’s point of view, the technology is decentralized, driven by the psychology of curiosity, such as Trump was convicted of AI-generated “arrested” images on the Internet (which is a kind of banter on politics). Furthermore, from the content itself, the high depth of Deepfakes technology makes it more difficult to recognize. Finally, from the regulatory level, the rapid pace of technological change, AI management norms lagging, which is also one of the reasons for Deepfakes.

2. Why Platforms Struggle to Respond?

Platform algorithms are not neutral, but rather a “platform politics” that subtly shapes social culture through content selection, design, and ranking (Massanari, 2017). The algorithm is actively deciding which data is pushed first and which is hidden (Musiani, 2013).

The platform recommendation algorithm is not based on “true or false” as the core standard, but on “user interaction”. AI-generated content is more likely to be recommended because of its emotional intensity and visual impact (Lazer et al., 2018).

There are also many “AI virtual accounts” on platforms such as TikTok and Twitter (X) – exquisite in appearance, sensational in copy, and unified in view, but in fact generated by AI. Such “digital accounts” publish content that is often mistaken for real people and are highly influential but difficult to regulate.

3. Case Study: When Deepfakes Go Mainstream

Globally, “fake news” with AI-generated content is constantly breaking the bottom line of information dissemination, not only covering politics and economics, but also penetrating cultural entertainment and visual psychology.

• White House explosion fake picture (2023): In 2023, an AI-generated “White House explosion” picture circulated on Twitter, and some mainstream accounts forwarded it, causing a short period of market panic, and the US stock market once fluctuated. The source of the image is fuzzy, and at first glance, it has a very “scene” feeling, but it was eventually proved to be a fake image.

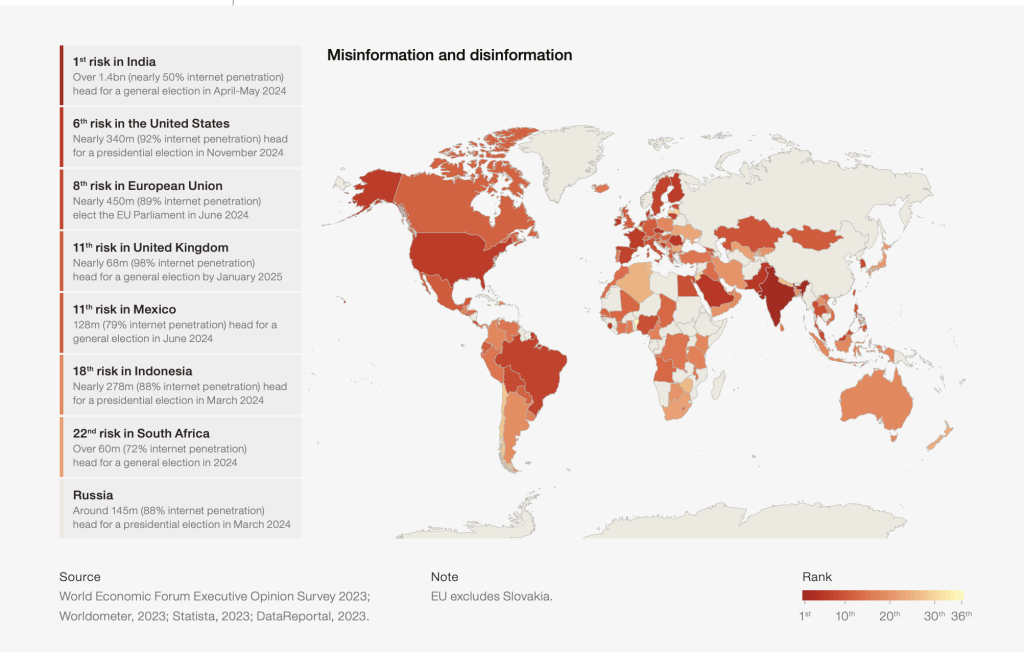

• Indian election AI video (2024): During the Indian election, a video of Prime Minister Modi “dancing” generated by netizens went viral on social platforms and was reposted by Modi’s official account. Although the video itself did not convey false information, it showed how politicians took the initiative to “leverage” AI entertainment content to enhance exposure and affinity. Some scholars have pointed out that this kind of “soft deepfake” is being used by politicians to attract young voters, blur the focus of public issues, and stabilize their influence in the information chaos (NBC News, 2024).

https://x.com/narendramodi/status/1787523212374393082

• “Spider Giraffe ” scary short video (2023): A type of AI video that specializes in creating “cognitive shocks” circulated on Instagram. In 10 seconds, everyday scenes suddenly mutate into bizarre monsters, which have been viewed billions of times. This type of “visual shock content” mainly stimulates the user’s fear circuit and controls screen time.

These cases show that the type of fake news has evolved from “identifiable rumors” to “immersive illusions.” They no longer persuade you through logic, but “conquer” you through emotions.

4. Why This Is More Dangerous Than Traditional Fake News?

Traditional fake news may be just word rumors, but the biggest feature of AI fraud is “visualization”: we are not searching for news, but “immersion”. Deepfakes images and audio and video are extremely deceptive, not only triggering emotions but also undermining the user’s rational judgment.

Users consume news not only to obtain information but also to confirm their self-identity (Kreiss, 2018). This means that we are more likely to believe content that “makes us feel reasonable.” Once you have an emotional connection with this content, the platform algorithm will “think you like” and push more similar content, forming an “echo chamber of false information” – the more you trust, the more you can’t avoid.

This “emotional cocoon” is being amplified by platform algorithms. What is even more worrying is that AI-generated content is not only misleading to individuals, but also more likely to shake the electoral system and the foundation of social trust.

According to the Global Risks Report 2024, disinformation and misleading content have emerged as one of the world’s most serious short-term threats, particularly at election time, which can shake the foundations of democracy.

5. Who Should Confront the Challenge of Deepfakes?

With the rapid development of generative AI and deepfake content, algorithms have become reality constructors – influencing what we see and believe (Just & Latzer, 2017). Therefore, we can no longer rely on the “user’s judgment” to identify the true and false. Platforms, governments and users must work together to build a new “digital trust mechanism”.

Policy: Strengthening Regulation and Clarifying Responsibilities

Governments are stepping up the deployment of laws and regulations to address AI-generated information:

• The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) promotes platform disclosure of algorithmic mechanisms to implement risk management for AI content.

• China’s “Regulations on the Management of In-depth Synthesis of Internet Information Services” require that all AI-synthesized images, videos, and audio must be marked significantly, and impose audit responsibilities on platforms.

• Australia’s online safety laws restrict social platforms from displaying dangerous content to minors, emphasizing rapid response mechanisms.

These policies are gradually clarifying the boundaries of rights and responsibilities between platforms, content providers and users.

Platforms: Upgrading Technology and Rethinking Gatekeeping

The central position of the Internet platform determines that it should take the first responsibility for Deepfakes and misinformation. The platform should carry out fact-checking and algorithm degradation mechanisms to timely intervene in conspiracy-type content.

• Meta develops an AI recognition system to add invisible watermarks to generated images.

• Sony launched biometric cameras that encrypt content from the source to prevent counterfeiting.

• Companies such as OpenAI and Google explored new monitoring tools that can identify whether images are generated by their AI models to help users distinguish between real and fake.

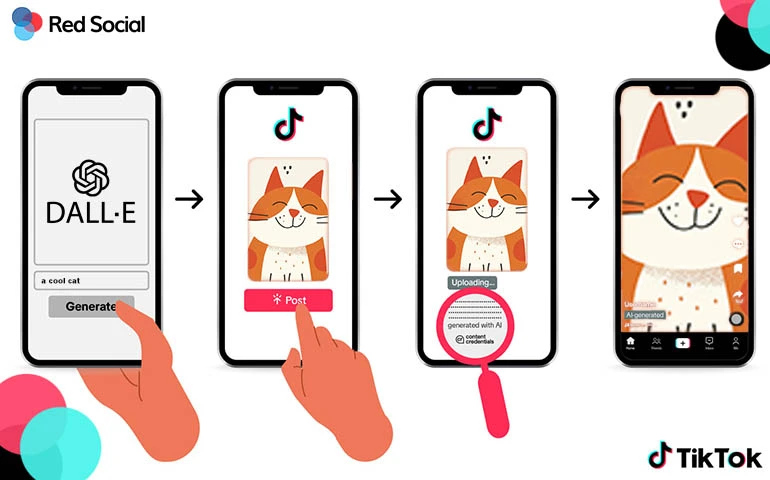

• TikTok is expanding its ability to automatically identify and label AI-generated content, covering content from external platforms.

These measures mark the formation of the “platform gatekeeper” mechanism, and mean that platforms can no longer use “neutral distribution” as an excuse to avoid responsibility.

Media: The Last Line of Defense for Truth

The authenticity and professionalism of news media is the key to breaking the cycle of false information.

• In crisis events, if mainstream media fails to speak up promptly, social platforms will quickly be overrun by “generative content”.

• Traditional media should speed up the transformation of digital intelligence, improve the verification mechanism, and establish an “anti-fake reporting cooperation mechanism”.

• In the face of Deepfakes, the media should not only clarify misinformation but also explain the mechanism to help the public build “AI immunity”.

Instead of reacting passively, journalism should become an important force in the governance of disinformation.

Users: Enhancing Digital Literacy to Detect Deepfakes

In the era of intelligent communication, the public should improve their online media literacy to protect themselves from Deepfakes.

• On the one hand, it is necessary to have information consumption literacy, preliminary identification, analysis and criticism of the content, and learn to cross-verify and verify the sources of pictures and videos on multiple platforms.

• On the other hand, it is also necessary to cultivate information production literacy, understand the public nature of forwarding and dissemination, and ensure that the information produced and shared by themselves does not become a booster of rumors.

AI chatbots are becoming an important tool for news communication, and AI has blurred the boundaries between the true and the false in the “virtual environment” and magnified the public’s reliance on information systems. As technology becomes more powerful, judgment must not deteriorate.

In the face of the impact of generative AI on public opinion ecology and social structure, the improvement of public literacy should become the lowest and most critical “defense line” in the information governance system. “The bottom line of people is the boundary of technology.”

6. Conclusion: Living with Fakes in a Platform-Driven World

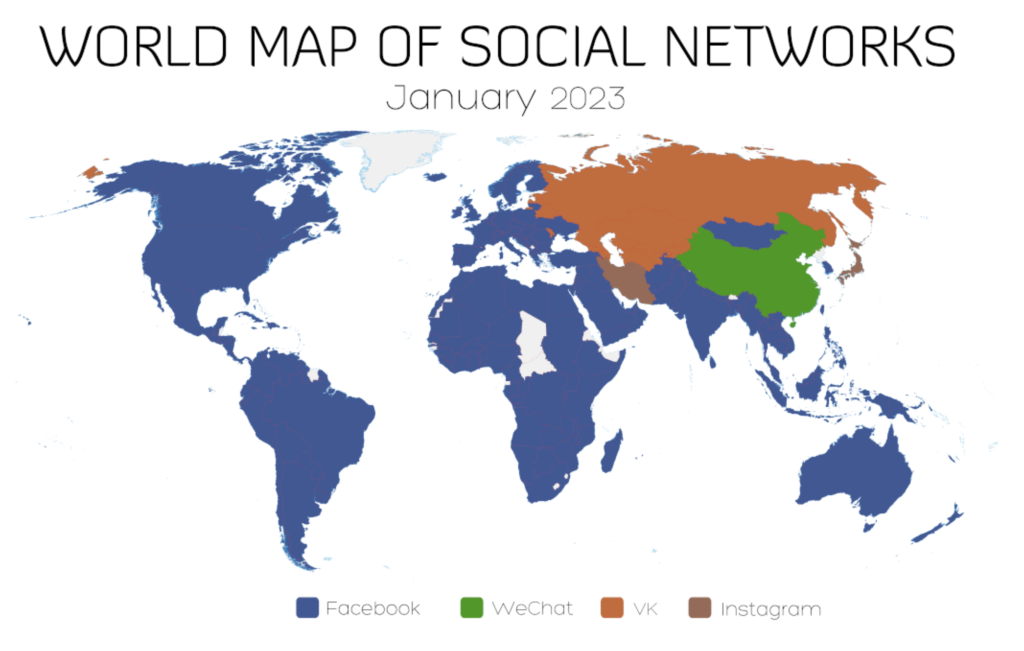

Today’s fake information continues to cross national borders, and the information ecology of different platforms has further widened the gap in “discourse power”. For example, Western mainstream social platforms push fake content about China, such as AI face-changing accounts with ambiguous political positions and manipulative public opinion videos, but it is difficult for Chinese local platforms to respond and refute rumors on these platforms. This “structural aphasia” means that many countries, like China, will become increasingly “passive” and “silent” in global information transmission.

Today’s information space is no longer an equal and open field of knowledge exchange, but a tug-of-war for global information power. In this battlefield, algorithms act as gatekeepers, traders, and even speech judges. Platform managers control the distribution of “who is heard and who is trusted.”

Derakhshan and Wardle (2017) call this “global information pollution,” in which a few platforms, with unequal algorithmic power, shape the majority’s imagination of the world. This is not technological backwardness, but the communication inequality caused by the fragmentation of social platforms. In the post-truth era, the authenticity of information is no longer determined by content, but by communication structures and social algorithms (Waisbord, 2018).

In the slums of Mumbai, women wipe their mobile phone screens with saris, saying it will “erase the lies in the video”. It may just be superstition, but their intuition was right – images can be deceiving. We can’t completely stop AI fraud, but we can build an “information immune system” at the platform, technology, and education levels. What really needs to be upgraded is our “digital judgment.”

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Derakhshan, H., & Wardle, C. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms (pp. 79–86). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Disinformation and fake news. In Regulating platforms (pp. 86–91). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fortune Business Insights. (2023). Fake Image Detection Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/fake-image-detection-market-110220

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 236–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kalpokas, I., & Kalpokiene, J. (2022). Deepfakes. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93802-4

Kreiss, D. (2018). The fragmenting of the civil sphere: Political conflict, social media, and the personalization of truth. In J. Alexander (Ed.), The crisis of journalism reconsidered (pp. 229–240). Cambridge University Press.

Massanari, A. (2017). Reddit and the toxic technocultures of gender: The trolling of Fat People Hate. In J. Daniels, K. Gregory, & A. Gray (Eds.), Digital sociologies (pp. 331–348). Bristol University Press.

Musiani, F. (2013). Algorithms and their politics. Internet Policy Review, 2(4), 1–12. https://policyreview.info/articles/news/algorithms-and-their-politics/244

NBC News. (2024, May 10). India’s election is being shaped by AI like no vote before. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/india-ai-changing-elections-world-rcna154838

Pasquale, F. (2015). The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Harvard University Press.

Waisbord, S. (2018). Truth is what happens to news: On journalism, fake news, and post-truth. In Brazilian Journalism Research, 14(3), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v14n3.2018.1044

Be the first to comment