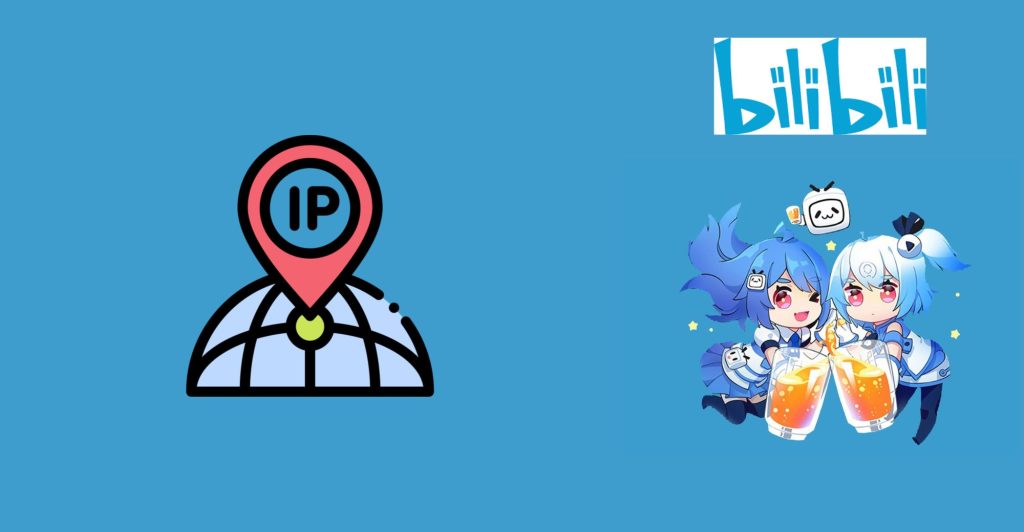

“Where are you from?” —— This question may not have been answered or asked by Chinese netizens on the internet for some time because they can see each other’s IP location clearly since 2022. User’s IP automatically shows the general location on their homepages and when they use social media platforms, including posting content, commenting, and resharing (see Figure 1). Showing IP locations belongs to the Qinglang Operation, a cyberspace governance campaign led by the Chinese government and jointly participated by multiple departments (Perkins Coie LLP, 2022). It aims to create a better internet environment in China by fighting misinformation and internet fraud.

Sounds good, right? But it’s not that simple. Showing IP addresses might seem like a step transformed from laws and regulations toward online accountability, but it opens the door to new forms of hate speech, discrimination, and online harms surrounding regions. Existing concerns about digital bullying mainly focus on gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation (Flew, 2021). However, even ageism has a proprietary vocabulary while the public pays less attention to regional discrimination. Regional discrimination refers to discrimination in a group based on their common birthplace (Peng, 2020), and this harmful phenomenon has been extended to internet users in the region because the IP Location shows is the place where they are currently staying, no matter what they were born there or not. This post will study online regional discrimination and rethink the balance between free speech absolutism and control online harm, and the future of online safety and digital governance in this context.

Figure 1. Chinese Social Media Platform REDNOTE Displays Users’ IP Addresses (This figure was created by the author.)

Growing Regional Discrimination ——The Good Idea of “Show IP Location” Gone Bad?

IP is the abbreviation of the internet protocol. IP location is important information because every internet user owns a unique IP address which ensures that their devices can send and receive messages, which is commonly known as surfing the internet. This address can further identify and reveal the user’s location by certain geolocation techniques. “Showing IP locations” brings this information easily overlooked into the public eye (Liu, Wu, Li, Song, & Hsu, 2024). This function requires that Chinese social media platforms compulsorily display the user’s provincial IP address when they express online in China, whether publishing various types of original content or forwarding others’ work. If users use Chinese platforms overseas, only the country will be displayed. This function has gradually be fully launched on mainstream Chinese social media platforms in the first half of 2022.

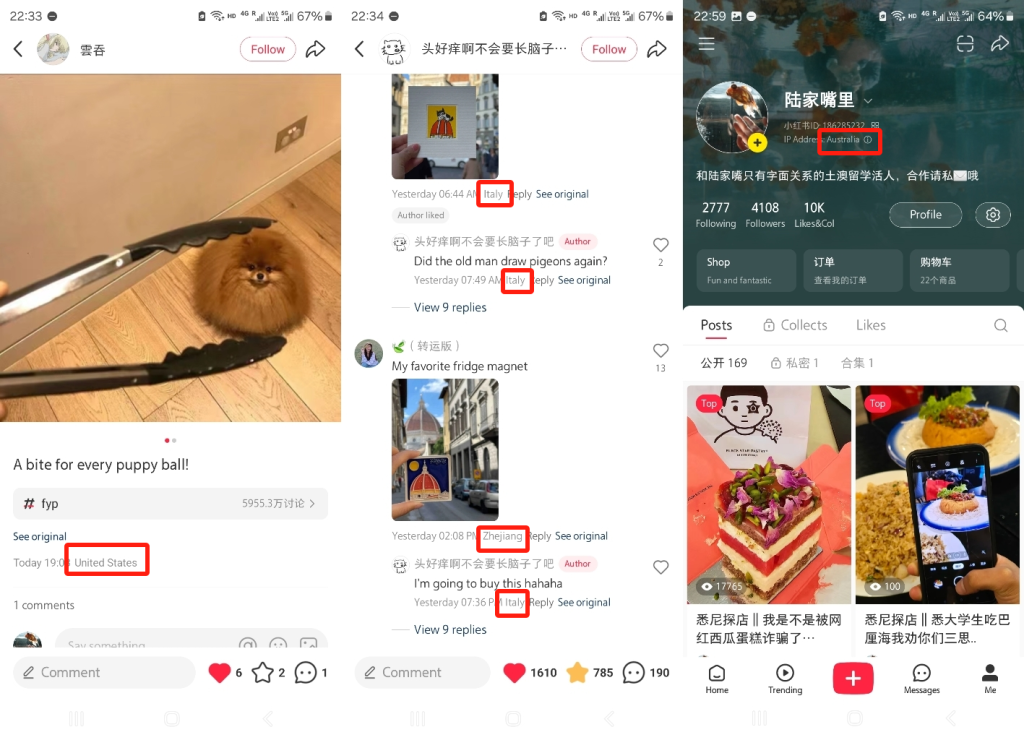

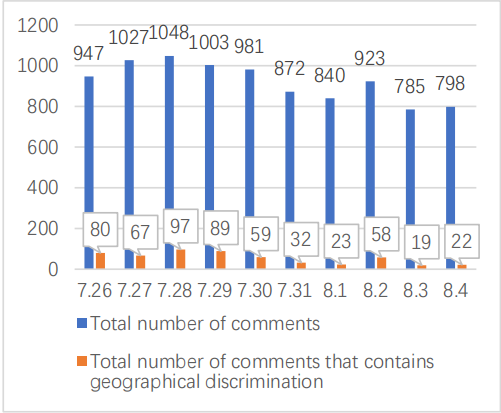

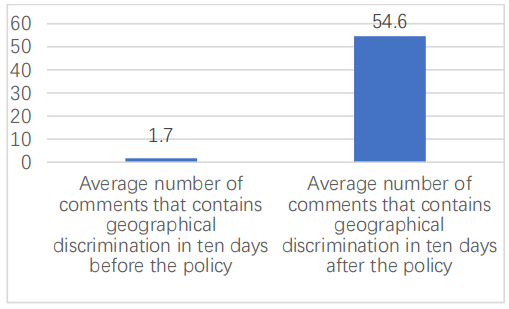

Concerns had been expressed about geographic hate speech before the release of this regulation. The researchers from Beijing Xishan School have decided to take “Bilibili”, a mainstream video platform for young Chinese, as their research subject, to study the likelihood of regional discrimination by the new policy. You may ask why Chinese netizens are convinced that Showing IP addresses will increase geographical discrimination. I would like to introduce the background here that regional discrimination is not a recent social phenomenon, but an old phenomenon with long-standing records in China. This is a complicated Chinese sociocultural outcome, and spread and change with the registered residence system, economic development, and media influence (Peng, 2020). Bilibili had announced that they would launch this function on 25 July 2022, so the researchers randomly selected a comment section under a popular video everyday in the first ten days before and after the implementation of this rule as samples to control for independent variables.

The results show a significant increase in regional discriminatory comments after the launch of “showing IP locations.” The videos for the last ten days contained an average of 36.4 times more than regional discriminatory comments before (see Figures 2, 3, 4). These comments can be divided into four main types. The first two are the most common geographically discriminatory in China and both are attributed to unbalanced regional development. One is regional stereotypes. They usually arise from some famous but negative events that mostly happened in one region and leave a deep impression on the public. This is often related to discrimination against the poor too because these events mostly occur in underdeveloped areas (Peng, 2020). Another is just the opposite. It is based on resentment of the rich. The main targets are those well-developed cities with tremendous resource advantages, which are commonly known as “big cities.” Then is international stereotypes, which are Chinese people’s attitudes towards other countries. This is because of fake news in the media and unfamiliarity with overseas life. The negative nationalist mentality is the last type but not very common. It is primarily due to important world events (Zhang, 2023).

Figure 2. Total number of comments and numbers of comments that contain geographical discrimination 10 days before the policy was enacted. (Zhang, 2023)

Figure 3. Total number of comments and number of comments that contain geographical discrimination 10 days after the policy was enacted. (Zhang, 2023)

Figure 4. The Average number of comments that contain geographical discrimination 10 days before and 10 days after the policy was enacted. (Zhang, 2023)

Regional discrimination used to occur in offline life, and internet users nearly had no chance to know other users’ locations directly even in the era of big data, so they were unable to directly send harmful speech to someone online. “Show IP address” policy compulsory discloses internet user information and places their IP locations in a relatively prominent position (Zhang, 2023). It expands online regional haters’ attention to IP and helps them find the target of harm, which is meant to reduce harms but create new ones.

Hate Speech, Digital Nationalism, and Digital Bordering

Hate speech conveys, encourages, and instigates hatred against a group of individuals according to their features. It discriminates and intimidates victims by emotional and violent language (Parekh, 2012, as cited in Flew, 2021). Hate speech has enlarged with the emergence of interactive digital platforms and has become a growing concern of issue. IP tags are not only locative information but also symbolic symbols shaped by sociocultural and economic construction, which is a global phenomenon. The locative design feeds digital discrimination and makes it more complex. People with different IP locations are all involved in this chaos because IP does not always accurately reflect the user’s regional identity because of population mobility (Peng, 2020). Significantly, hate speech doesn’t always come with abuse and direct threats. It can be a negative attitude and obscure, and sometimes even disguised as “patriotism.” For example, defaming overseas IP users by “interfering in the internal affairs of other countries” when they comment an event in another country.

In more serious cases, online regional discrimination, especially those with radical patriotism, will become extreme digital nationalism. Nationalism is an ideology based on one’s ethnicity, originating from a strong identification with one’s nationality (Heang, 2024). The global rise of the internet frees nationalism’s expression from the constraints of geography. Digital nationalism brings nationalism from the government to individuals. Online users can express their national belonging while challenging others’ national identity daily (Ahmad, 2022). Digital nationalism relies on the conflict framework of ‘us vs them’, so the display of IP location may simplify complex issues into binary oppositions of “patriotic or not”, and create regional conflicts to transfer social contradictions. For example, some users’ loyalty and authenticity of speech may be doubted if their IP shows outside the region of speech focus. In digital nationalism disputes, IP is closely connected to the social psychology of belonging and exclusivity, credibility, and stigmatization. From this, we can see that IP address is not only a network location tool, but also contains geographical information. When the platforms actively display the user’s IP location, it essentially links network behavior with geographic identity, strengthening the territorial boundaries in digital space (Deibert, 2020). However, should we let geographical location determine how we can trust or hate someone online?

The Outcome —— Protection or Prohibition? Safety or Surveillance?

The effect of IP localization mainly focuses on cleaning up China’s online environment, such as striking the internet army, suppressing false information, and deterring online criminals and keyboard men. Many scholars believe that IP locality transparency can also provide netizens with more dimensions of reference. For the users, the function protects them from malicious rumor-mongering, fake news, and clot-chasing users. However, it is worth noting that these positive results are mostly just theoretical on the level of discussion. The consequences are not as simple as hate speech causing harm to victims and regional groups.

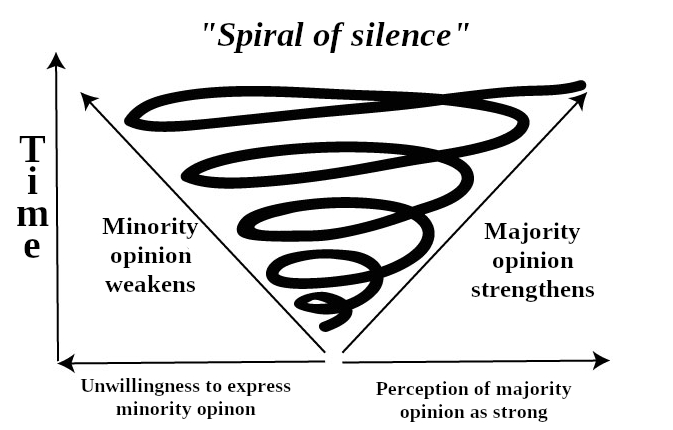

I will introduce a mass communication theory, Spiral of Silence, here (see Figure 5). This theory states that individuals’ perception of public opinion can affect their willingness to express their views. In other words, individuals cannot completely avoid being influenced by the words of others, and a sense of security is the foundation for individuals to express their opinions, including on the Internet (Spiral of silence, 2025). Showing IP addresses increases the risk of exposure to harm when netizens surf the internet. To protect themselves, people usually choose to keep silent and learn to be disaffected. When they feel risks and exercise self-restraint, the emotional tendency, diversity, and readability of online speech are changed through subtle influence (LE, KONG, & DUAN, 2024). The result is a clean but narrower digital space created.

Figure 5. The Theory of Spiral of Silence (Wikipedia, 2025)

In addition, here is a question that has the disclosure of users’ IP location obtained their consent. I will not answer this question, after all, it has become an inevitable outcome. However, many people neglect that this data is a form of personal privacy when they passionately discuss IP addresses online. The exposure of this type of information exposes the possibility of online harm extending offline, such as doxxing and tracking, just like the outcome of other real-life privacy information leaking. At this point, it can be seen that transparency is not entirely equivalent to security and it even brings security issues because personal information has shifted from being regulated by platforms to being monitored by the public.

Rethinking Digital Governance —— Who’s in Charge?

The original intention of showing IP addresses is to protect Internet users and the online environment. However, what happens when it leads to targeted harassment, hate speech, or other harm? Who’s responsible for these consequences, the platform, the government, or someone else entirely? Behind every governance policy, not only showing IP locations but also others, lies a complex web of power.

Firstly, as the “information gatekeeper”, those social media platforms have extraordinary control (Flew, 2021). However, some large enterprises, like Google and Meta, are found to use the identity of neutral intermediary and asymmetric information to interface visible content on social media and change the platform policies silently, though there are some constitutions for the internet, like the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (Kausche, & Weiss, 2024). If the state governs on the platforms’ behalf, governance may be imbalanced because of political differences. As mentioned earlier, the EU imposes restrictions on Internet companies, but these companies enjoy great autonomy and the EU is unable to monitor their behaviors. In contrast, network governance is led by the governments in some countries with centralized power, but digital technologies may serve surveillance capitalism and restrict the speech freedoms of citizens (Olszewska, 2023). Additionally, the criteria of hate speech is hard to define because of the serious dependence on regional culture. However, many social media applications are worldwide, so the difficulty of applying global community standards has increased (Sinpeng, Martin, Gelber, & Shields, 2021).

Even if there is no “Showing IP Location” policy, these imbalances lead to users from all over the world, who are under online attack, being treated differently, not because they cannot be considered harmed, but because the policies are inconsistent. It is necessary to adjust the frame of digital platforms’ governance gradually to solve this issue and make platform rules more democratic and globally fair. I think it is more important to introduce co-governance models, which means platforms working with governments, researchers, and communities, compared to debating who leads governance. Studies show that this model will act more effectively when diverse stakeholders work together because a variety of governance strategies stimulate value co-creation and cover more groups relatively (Xiao, & Ke, 2024). The diversity also includes diverse voices in online speech. Even though multiple voices can easily lead to conflicts, studies show that these people will increase mutual understanding and trust in communication, and high trust brings more positive effects (Siddiki, Kim, & Leach, 2017). The platforms can also do some practical behaviors like publishing clearer appeals processes and replying to them actively when users actually suffer from network damage.

In conclusion, IP is more than just a dot on the map and is related to other information. However, it should not decide how people are treated online. This question ultimately boils down to how internet regulation manages online hate speech. We should rethink the frame of digital governance, then we can build a not just safer, but fairer online environment for everyone.

Reference

Perkins Coie LLP. (2022). Enforcement trends from China’s cyberspace regulator in 2022. Perkins Coie.

https://perkinscoie.com/insights/update/enforcement-trends-chinas-cyberspace-regulator-2022.

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. Regulating Platforms.79-86.

Peng, A. Y. (2020). Amplification of regional discrimination on Chinese news portals: An affective critical discourse analysis. Convergence, 27(5), 1343-1359.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520977851.

Liu, Y., Wu, Y., Li, C., Song, C., & Hsu, W. (2024). Does displaying one’s IP location influence users’ privacy behavior on social media? Evidence from China’s Weibo. Telecommunications Policy, 48(5).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2024.102759.

Zhang, X. (2023). The Impact of the “Show IP Location” Policy on Geographical Discrimination Based on the Comments on Mainstream Chinese Youth Video Websites “Bilibili”. BCP Social Sciences & Humanities, 21, 163-169.

https://doi.org/10.54691/bcpssh.v21i.3462.

Heang, R. (2024). Digital Nationalism: Understanding the Power of Digital Technology in the Rise of Nationalism, National Identity, and National Narratives. Open Access Library Journal, 11, 1-26.

Ahmad, P. (2022). Digital nationalism as an emergent subfield of nationalism studies. The state of the field and key issues. National Identities, 24(4), 307–317.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2022.2050196.

Deibert, R. (2020). Part 4: Digital authoritarianism: How technology designed to empower us was seized by autocrats. Reset: Reclaiming the Internet for Civil Society.

Spiral of silence. (2025). In Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spiral_of_silence#.

LE, C., KONG, W., & DUAN, N. (2024). The Impacts of IP Localization Policy on Public Opinion Comments: A Quasi-natural Experiment Based on the Display of IP Location on Weibo Users. Documentation, Informaiton & Knowledge, 41(1), 46-57.

https://dik.whu.edu.cn/jwk3/tsqbzs/EN/10.13366/j.dik.2024.01.046.

Kausche, K., & Weiss, M. (2024). Platform power and regulatory capture in digital governance. Business and Politics.

https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2024.33.

Olszewska, K. (2023). Cyfrowy nadzór w chińskim modelu autorytarnego kapitalizmu. Studia nad Autorytaryzmem i Totalitaryzmem.

https://doi.org/10.19195/2300-7249.44.3.5.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Executive summary. In Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. 1–2.

https://hdl.handle.net/2123/25116.3.

Xiao, L., & Ke, T. (2024). Influence of platform governance and community diversity on users’ value co-creation in sharing platform? Insights from China. The International Journal of Logistics Management.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlm-10-2023-0415.

Siddiki, S., Kim, J., & Leach, W. (2017). Diversity, Trust, and Social Learning in Collaborative Governance. Public Administration Review, 77, 863-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/PUAR.12800.

Be the first to comment