Imagine this: You post a harmless comment online — maybe something like, “First class seats are really comfy.” A stranger takes offense. Hours later, your real name is trending on social media. Strangers are messaging your family. Your workplace is flooded with angry calls. Someone leaks your home address. And worst of all, you’re pregnant — and the messages in your inbox are wishing you a miscarriage.

No, this isn’t a dystopian episode of Black Mirror. This happened in China. In 2025.

And it’s not even rare.

On the Chinese internet, this practice has a name: “kaihe” (开盒), or “opening the box”. It refers to the act of doxxing someone — digging up and exposing their personal information online, usually as revenge or punishment. Sometimes it’s done by obsessive fans, sometimes by angry strangers, and increasingly, it’s done using massive, unregulated databases floating around in the shadows of Telegram and other platforms.

In 2018, the The Pew Research Center found that 91% of American adults agreed or strongly agreed that consumers have lost control of how personal information is collected and used by companies and that only 9% of those surveyed were “very confident” that social media companies would protect their data (Flew, 2021). Nowadays, privacy issues have arisen for almost all digital platform companies.

The Baidu Doxxing Scandal: How a Comment Became a Crisis

In March 2025, a pregnant woman in China commented on Korean celebrity Jang Wonyoung’s travel post on the platform Weibo, saying that “sleeping in first class is really comfortable.” What she probably didn’t expect was that this would trigger a vicious online attack by the celebrity’s extreme fans. It didn’t stop at name-calling. The woman’s personal information was illegally uncovered and shared online — including where she worked, her home address, and her husband’s phone number. She was harassed with messages wishing her a miscarriage, and her husband also received abusive texts.

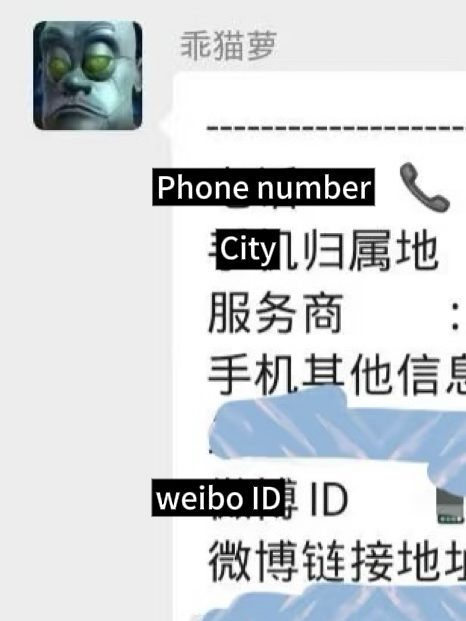

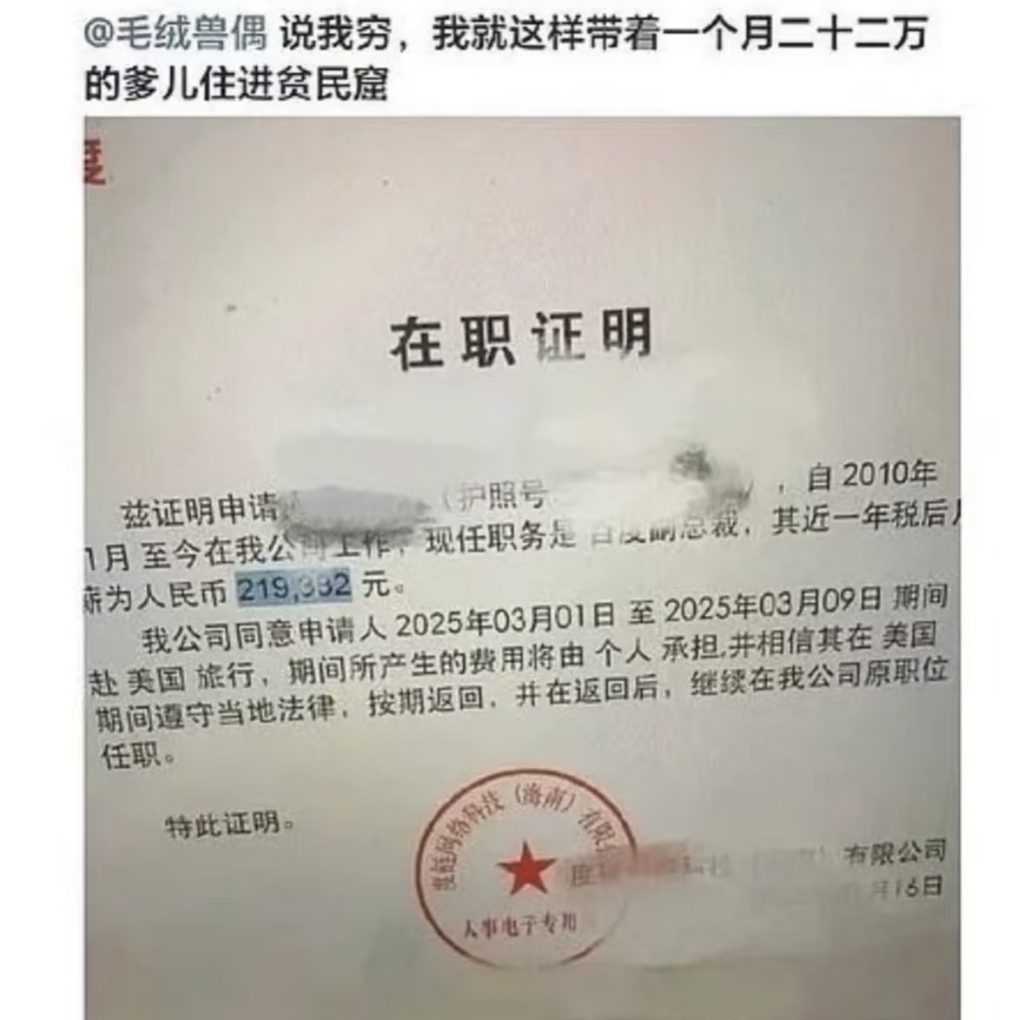

Internet users later discovered that the person behind the attack was allegedly the daughter of a senior executive at Baidu, one of China’s biggest tech companies. Screenshots showed her posting documents related to her father’s income and job title, implying that she had special access to personal data from Baidu.

The internet exploded with outrage. What made this incident so unsettling wasn’t just that someone’s personal information got leaked , which is not rare in today’s digital world. The woman had shared a casual opinion on a public platform. She didn’t expect her words to be totally private, but she did expect that her comment wouldn’t travel beyond that specific context or be used to track down her real identity.

A few days later, Baidu stepped in to respond to the growing outrage. In an official statement issued on March 19, the company firmly denied that the leaked personal data had come from its internal systems. According to their investigation, the information had been sourced from a third-party “social engineering database” hosted overseas — primarily through the messaging platform Telegram. Baidu even provided notarized documentation to support this claim and clarified that the viral screenshots suggesting the girl had received a “family database” were fabricated.

From a technical perspective, the explanation made sense. China has long struggled with the black market of leaked personal data — databases compiled through phishing scams, data breaches, and shadowy internet forums. In this case, it appeared that the Baidu executive’s daughter had simply used publicly available (albeit illegally obtained) data, rather than tapping into any special corporate access.

Data Markets and Governance Vacuums: Where Privacy Really Breaks Down

If anything, Baidu’s clarification only exposed a deeper, more troubling issue. The real threat to digital privacy isn’t just what platforms do with your data. It’s what they fail to stop others from doing with it. In this case, the individual who exposed the data had no official access. She had no legal warrant. She didn’t even need technical expertise. She simply opened Telegram. There, she reportedly found a full personal profile — names, addresses, phone numbers, and more. That should be the real focus of our concern.

The leaked data was reportedly pulled from a social engineering “info dump”. These dumps are collections of personal information gathered over many years. Sources include phishing scams, poorly secured websites, and breached public databases. The data is often bundled, sold, or shared in bulk. It includes names, ID numbers, contact details, school records, and employment histories. Once leaked, this data cannot be recovered. It exists beyond the control of any one platform or national legal system. Instead, it circulates in a shadowy international space, where accountability is rare and demand is constant.

The terrifying thing about this case is not that someone’s data was leaked. It’s that the system allows it to happen all the time, and no one seems responsible. The Baidu executive’s daughter didn’t hack anything. She didn’t need to. Telegram, like many other platforms, is home to massive black market databases, built on years of breaches, scraping, and phishing with no meaningful regulation in sight.

Privacy is not a passive right — it is a positive one (Karppinen, K., 2017). In other words, privacy doesn’t just mean “no one harms you.” It demands that society take active steps to protect it. These steps include legal safeguards, institutional accountability, and enforceable public norms.

When users are expected to protect themselves from international data brokers and shadowy platforms, it’s not empowerment. It’s abandonment. And the more platforms rely on behavioral data to function, the more this burden of protection gets pushed down onto the individual, while the structural power to exploit remains intact. That’s not a privacy framework. That’s a failure to govern.

Meanwhile, regulation lags behind. There are few binding international mechanisms for holding companies (or entire platforms like Telegram) accountable for hosting illegal databases. Even when governments respond, their actions are often limited and reactive. Enforcement usually targets only the most publicized cases. For most users, there are no alerts. No audit trails. No way to know who accessed their data, or when. You don’t realize your information has been exposed until long after it’s too late.

It is no longer about a single platform. It’s a story about governance failure in the global data economy. Digital rights are not natural extensions of human rights. They are political, unevenly distributed, and constantly contested (Karppinen, K., 2017). On today’s internet, privacy is not protected by default. It is something you have to fight for, if you even realize it’s been taken from you.

So what can be done?

Of course, users need better education on privacy: be careful what you share, don’t click suspicious links, don’t reuse passwords, always read the fine print. But this individualized model of privacy assumes that leaks are personal failures, rather than the result of systemic neglect. Our behavior is increasingly mined for “behavioral surplus” — data that platforms collect not to serve us, but to predict and profit from us. In such a system, even the most careful user is still a data point (Zuboff, S.,2019).

But more importantly, we need infrastructures that don’t make safety a personal burden. Because the question isn’t whether our data will leak. It’s whether we’ve built a world where that risk belongs to everyone, or just to the powerless. At the very least, governments need to build cross-border legal frameworks that hold platforms accountable for enabling data markets and provide real recourse when leaks happen. Platforms should make data access logs visible and accessible, and give users a clear record of where their information has traveled.

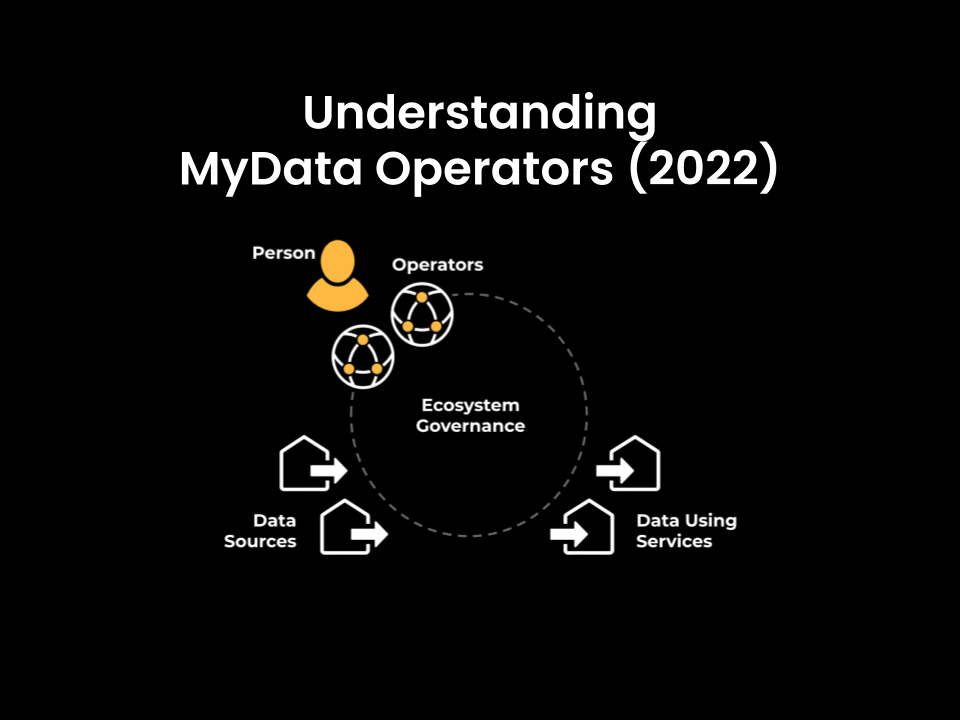

One model worth looking at comes from Finland. The MyData initiative, which began there and has since grown into a global movement, offers a radically different approach to data governance — one that puts users, not platforms, at the center of control.

Under the MyData model, individuals are not passive data subjects. They are active agents with the right to see who has accessed their information, when, for what purpose, and under what legal basis. Data is not just collected and stored in corporate silos. It is made transparent and portable, with the idea that people should be able to manage their personal data as easily as they manage their bank accounts.

This vision is already being tested in sectors like healthcare, education, and mobility. In these systems, users can review access logs, grant or revoke permissions, and understand how their data is moving across institutions in clear language. It’s not perfect. But it’s proof that a different data infrastructure is possible: one where visibility and accountability are built into the system by design, not just promised after a scandal. Compared to platforms that bury data flows in legalese and obscure interfaces, MyData offers something rare in the digital world: dignity.

The Politics of Digital Trust: Why Platform Power Still Fails the Public

Part of what made the public backlash so intense wasn’t just what happened, but how little recourse there was. When Baidu said, “It wasn’t us,” there was no way to know if that was true, or how they came to that conclusion. There was no audit, no independent oversight, no explanation beyond the company’s own word. And that’s exactly the problem.

Platforms today operate as quasi-sovereign spaces. They write their own rules (through Terms of Service), enforce them as they wish, and rarely allow users to question, appeal, or even understand those decisions. This is not governance in any meaningful democratic sense. It’s governance without representation — a system where the users have no voice, and no visibility into the process (Suzor, N., West, S. M., Quodling, A., & York, J. C., 2018).

In such a structure, trust collapses not because platforms make mistakes, but because they own the entire definition of what counts as a mistake. When a user is harmed, the question isn’t “what happened?”, but “what is the platform willing to admit happened?” And that gap, between user experience and platform narrative, is where public suspicion lives.

The real question, in the end, might not be where the data came from, but why so many people instantly believed it came from Baidu. The public wasn’t just being paranoid. Their instinct came from experience.

In the age of platforms, our expectations around privacy have quietly eroded. Privacy isn’t about secrecy but “contextual integrity”: the idea that we expect our information staying where it’s supposed to stay within the social context it was given. When you leave a comment on Weibo, you know it’s public. But you don’t expect that comment to lead to someone digging up your home address, your family members, and your workplace. That kind of cross-contextual information flow breaks a social expectation, even if it doesn’t technically break a law (Nissenbaum, H., 2004). When something we posted casually on social media ends up fueling a targeted attack, that integrity is broken. It doesn’t matter whether the leak came from a company server or a shady forum. What matters is that we’ve come to believe the boundary can, and will, be crossed.

And this is why so many people believed the data must have come from Baidu: it felt too intimate, too precise, too fast. That instinct wasn’t irrational. It came from a collective sense that platforms, with their vast data resources and opaque rules, can enable such boundary-crossings anytime. Whether or not they actually did becomes almost irrelevant, because the damage lies in what users believe is possible, not what can be proven.

And that belief didn’t appear out of nowhere. It emerged from years of opaque platform governance, where the rules are written by companies, enforced inconsistently, and rarely open to challenge. As scholars have pointed out, platforms govern through Terms of Service, not through democratic processes. Users are subjects, not citizens. When things go wrong, there is no court, no clear appeal, no external review. All we have is what the platform says happened.

So when Baidu says, “It wasn’t us,” maybe they’re telling the truth. But the public reaction says something more enduring: we no longer trust platforms to be honest brokers of our data, or to hold their power in check. That kind of trust isn’t restored through PR statements. It has to be earned, through transparency, accountability, and shared governance.

Years ago, Baidu’s CEO Robin Li famously said that “Chinese people are willing to trade privacy for convenience“. But what if no one ever actually made that choice? What if it was made for them, not by design, but by the absence of meaningful alternatives?

Because in a world where privacy can be selectively enforced, it’s not a right. It’s a privilege. And privilege, by definition, is not something everyone gets to have.

References:

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 79–86)

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In J. Trappel et al. (Eds.), The Media for Democracy Monitor 2017 (pp. 95–101). Nordicom.

MyData Global. (n.d.). MyData: A human-centric approach to personal data. Retrieved April 12, 2025, from https://mydata.org

Nissenbaum, H. (2004). Privacy as contextual integrity. Washington Law Review, 79(1), 119–158.

Reuters. (2025, March 20). China’s Baidu denies data breach after executive’s daughter leaks personal info. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/cybersecurity/chinas-baidu-denies-data-breach-after-executives-daughter-leaks-personal-info-2025-03-20/

Suzor, N., West, S. M., Quodling, A., & York, J. C. (2018). What do we mean when we talk about transparency? Toward meaningful transparency in commercial content moderation. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1526–1543.

Technode. (2025, March 20). Baidu exec’s teen daughter linked to doxing scandal using overseas data in online dispute. TechNode. https://technode.com/2025/03/20/baidu-execs-teen-daughter-linked-to-doxing-scandal-using-overseas-data-in-online-dispute/

Be the first to comment