Image source: Anquanke (2023)

Have you ever imagined just a genetic test you can easily do at home could lead to the leakage of your sensitive information? Did you realise that when the database of a biological company’s database is attacked, you are not the only person being affected?

Not only are there personal identity and privacy issues involved, but your loved ones may also be implicated. It may even affect the security of your entire family’s genetic information.

In the era of big data, these seemingly distant privacy breaches are no longer a stuff in science fiction.

Image source: 699pic.com

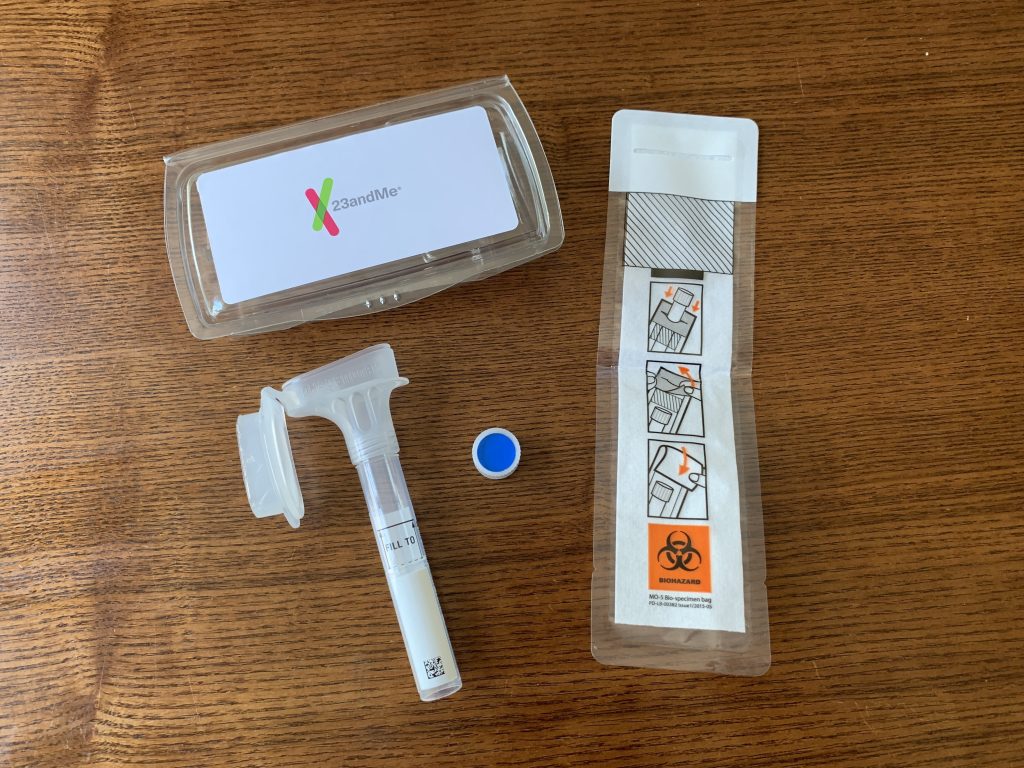

DNA testing kits have been a very popular activity over the past decade. Many people consider it a fun activity to explore genetic mysteries or predict health risks. In this case, companies like 23andMe & AncestryDNA commercialised genetic testing.

It used as a holiday gift or to locate relatives or family members (Hodge, 2024). Behind the seemingly ‘fun’ tests, however, is an ever-expanding system of storing, analysing and monetising genetic data.

Only few people realise that once uploaded, their own and their family’s genes are entered into a huge database. They data can be accessed, misused or even stolen for illgeal purposes.

In October 2023, this fear turned into a reality. The famous genetic testing company 23andMe experienced a major data breach, exposing a vast amount of users’ sensitive genetic information.

This blog will analyse this incident in depth and explore the broader challenges to personal privacy, data security, and digital rights in the age of big data.

Key concepts: privacy, security and digital rights

To understand the full impact of the 23andMe genetic data breach, it is important to be clear about some key concepts.

Privacy: The legal concept of the right to privacy was first systematically introduced by Warren and Brandeis (1890) in their landmark article The Right to Privacy, published in the Harvard Law Review. They famously described privacy as “the right to be alone “.

Information Privacy: According to the International Association of Privacy Professionals (n.d.), information privacy is “the right to have some control over how your personal information is collected and used.”

Personal data security: It is the measures taken to protect personal information from unauthorised access and disclosure. This covers attributes such as ‘identifiability’ and ‘recordability’ of personal data. (Chen, 2023)

Digital rights:

It refers to a set of basic human rights that individuals should enjoy in the digital environment, including freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy protection. With the development of technology, these rights have become increasingly important. But it also face challenges from surveillance, data control and policy decisions. (Karppinen, 2017)

Background information about 23andMe

23andMe Holding Co. is a privately held American genetics and health company headquartered in California. Customers simply provide a saliva sample by mail, which is analysed and tested in a laboratory to obtain a detailed report on ancestry analysis and genetic health risk assessment.

While the company promotes it as a way for users to take control of their personal biological information, it actually collects and stores large amounts of sensitive genetic data in the background.If accessed without authorization, these data could result in serious and irreversible effects.

Many users don’t realise that what they are handing over. It is not only their own and their family’s data, but also core vital information that can be reused, sold or even used for commercial research.

Image source: PCWorld

23andMe Data Breach

In October 2023, 23andMe confirmed that it had been targeted to a ‘credential stuffing attack’. Hackers attempted to log in to the 23andMe platform using account information leaked by users on other websites, successfully compromising approximately 14,000 accounts.

Because 23andMe’s DNA Relatives feature creates genetic matches between users, the attackers were able to indirectly access a large number of users’ information through a limited number of compromised accounts. Ultimately, more than 5.5 million people are affected.

These leaked data included users’ names, places of birth, years of birth, ethnic backgrounds, genealogical relationships, percentage of DNA matches with relatives, and health reports (e.g., disease risk, carrier status, etc.) for some users. Raw DNA data was also downloaded.

The incident exposed multiple security vulnerabilities:

· Prevalent password reuse by users, making credential padding an efficient attack method;

· Lack of multi-factor authentication (MFA) exacerbates account risk;

· DNA genealogical networks are highly interconnected, leading to the possibility of exposing data about family members even if the accounts themselves have not been compromised.

Image source: Network ATS

This company inform its users to change their passwords on 10 October 2023 and enforced two-factor authentication (MFA) on 6 November, temporarily shutting down parts of DNA Relatives.

23andMe also hired a third-party security firm to assist in the investigation. It is also working with law enforcement to find out where the leaked data came from and how far it has spread.

It also worked to remove copies of the data that have been recirculated on third-party websites and to strengthen its system security mechanisms.

23andMe filleda legal document with the California Attorney General that gives users several recommendations, including:

· Check to see if you are using the same account password on other platforms

· Viewing and adjusting private letters shared in 23andMe accounts

· Monitoring individuals for identity theft risks

Requesting a credit report freeze, fraud alert or contacting an identity theft response agency as needed.

In addition, 23andMe provides users with contact information for the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, the three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion), and state state offices for use in defending their rights or getting help.

Despite implementing various measures and offering guidance to affected users, the company remained caught in a storm of public criticism. It has became the target of class-action lawsuits.

At the same time, the company was being investigated by U.S. and European regulators for alleged violations of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Public trust in the company and similar genetic testing services has declined significantly. On social media, a large number of users of users posted screenshots of deleted accounts and demanded that the company disclose the truth about the incident.

Public interest organisations have called for users’ genetic data to be protected in the same way as medical and health information, for example genetic data should be covered by HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act).

The data breach has greatly damaged 23andMe’s reputation. It filed for bankruptcy in the U.S. in March 2025 as demand for genetic testing dried up over the last two years .

Information leaks in biotech are not an uncommon occurrence in the age of big data. In 2018, MyHeritage leaked information on over 92 million accounts.

What these incidents show is that biodata companies generally fail to build security defences that match the sensitivity of their data.

Deep Dive: Systemic Gaps and Ethical Warnings

The occurrence of such incidents is not an isolated security breach, but in a way reveals more fundamental institutional flaws in the digital governance system.

Firstly, public awareness of data risks is very weak and needs to be urgently raised. Many users do not realise that using the same password for multiple different platforms and uploading highly sensitive genetic information without careful thought could lead to very serious consequences for personal privacy.

Secondly, biotech companies have neglected their security and social responsibilities in the pursuit of commercial interests and optimisation of user experience. For example, they do not enforce multi-factor authentication, do not impose sufficient access restrictions on data access, and fail to detect and stop data breaches when they occur.

More importantly, the protection of genetic data in the existing legal system is lagging behind the development of technology. Many countries have yet to develop specific laws and policies to handle and protect such sensitive information.

The lack of regulation has led some biotech companies to operate in a grey area. Hackers and other unauthorized parties access genetic data through various illegal methods.

From a theoretical perspective:

Privacy balance theory (Laughlin & Westin, 1968) suggests that individuals continuously negotiate the balance between privacy and information sharing in order to adapt to social environments and norms. However, 23andMe’s ‘simplified login’ for users sacrifices basic security and focuses too much on convenience.

Contextual integrity theory (Nissenbaum, 2004) suggests that user authorisation should be limited to specific scenarios. The data breach clearly went beyond the original expectations and consent of the users.

Solove (2006) and Regan (2015) emphasise that real privacy harm often comes from long-term data aggregation and profiling behaviour. This breach is not just about a single point of data leakage, but a network of relationships.

The commercialisation of genetic data also raises significant moral and ethical issues. Biotechnology companies not only sell genetic testing services, but also share data with pharmaceutical companies for commercial research. Users themselves know little about it, let alone can participate in it.

This mismatch of information and rights can have serious and irreversible consequences. These barriers pose a significant challenge to ‘data justice’.

From a cultural perspective, such incidents may deepen distrust of biomedicine within certain communities.

Groups that have suffered from medical discrimination may be more reluctant to participate in related services or research as a result. Historical examples of unethical experimentation and lack of informed consent—such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study or forced sterilization programs—have left lasting trauma and intergenerational skepticism toward health systems.

Image source: National Archives via DocsTeach

When modern genetic platforms experience security failures or partner with law enforcement, these memories are reactivated and amplify hesitation among marginalized populations.

In turn, this growing mistrust can reduce participation in genetic studies and public health initiatives, ultimately affecting both the equity of healthcare access and the inclusivity of scientific research outcomes.

Public health systems depend on diverse datasets to draw accurate, generalizable conclusions. When certain communities opt out, not only are they underrepresented, but solutions developed may also fail to address their specific needs.

At the same time, another concern has emerged. Genetic data may be used inappropriately by governments or law enforcement agencies.

Given that commercial companies are already driven by profit and may overlook data protection, the involvement of state agencies in accessing or using such data for investigations could present even greater risks to privacy.

When genetic data that was voluntarily submitted for personal curiosity or medical insights is repurposed for surveillance, it challenges the boundaries of consent and undermines user autonomy.

This trend of ‘voluntary uploading by users’ gradually evolving into a ‘tool for state surveillance’ warrants a high degree of vigilance. Without strict oversight, even well-intentioned use of genetic databases by governments could lead to profiling, discrimination, or misuse, particularly against vulnerable populations.

Conclusion and Suggestions

This genetic data breach is a powerful reminder to the global community. In the digital age, we not only need to protect the data itself, but also rethink who should have control over the data and who should be responsible for its security.

Users: Develop good password setting and management habits. Pay attention to privacy agreements. And choose data platforms carefully;

Enterprises: Must practice focusing on the protection of users’ private data and implement encryption, verification and notification obligations. Assume social responsibility.

Regulators: More enforceable laws are needed, such as a ‘genetic privacy bill’ or inclusion in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) framework;

The public and education system: greater efforts should be made to promote digital rights and privacy literacy, from school education to social advocacy.

In the era of deep integration of digital and biological data, we can no longer passively wait for the next 23andMe-like data breach to happen. We must consider digital rights as part of civil rights. Only then can we truly protect the privacy and dignity written in our genes.

References

Warren, S. D., & Brandeis, L. D. (1890). The Right to Privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/1321160

International Association of Privacy Professionals. (n.d.). What is privacy? Retrieved April 12, 2025, from https://iapp.org/about/what-is-privacy/

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Chen, T. (2023). Personal Information Leakage Threats and Suggestions for Improvement in China’s Epidemic Prevention and Control. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research/Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 2352-5398, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-38476-128-9_40

Laughlin, S. K., & Westin, A. F. (1968). Privacy and Freedom. Michigan Law Review, 66(5), 1064–1074. https://doi.org/10.2307/1287193

Nissenbaum, H. (2004). Privacy as Contextual Integrity Privacy as Contextual Integrity PRIVACY AS CONTEXTUAL INTEGRITY. Washington Law Review Washington Law Review, 79, 119–157. https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol79/iss1/10/

Solove, D. J. (2006). A taxonomy of privacy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 154(3), 477–560. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol154/iss3/1/

Regan, P. M. (2015). Privacy and the common good revisited. Privacy and the Common Good. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290315805_Privacy_and_the_common_good_Revisited

Be the first to comment