Have you ever used ChatGPT? Maybe when you were stuck writing an essay, looking up how to make a tiramisu, or just trying to decide what to eat for dinner. This kind of AI seems incredibly smart, and it can produce a well-structured, logically sound, and confidentially worded answer in seconds. Sometimes, it even seems more reliable than we are ourselves.

Have you ever wondered how these “decisions” are actually made? We accept its answers, quote them, and even make judgments based on them, but we rarely ask, why did it say that? Could it be wrong? These questions often slip by unnoticed because it is just so easy to trust it.

ChatGPT and other generative AIs are rapidly entering our daily lives, but they are not as neutral or harmless as they appear. They are trained on massive amounts of past data, which is full of biases, mistakes, and hidden assumptions we can‘t always see. More importantly, when they do make mistakes, it is unclear who should be held accountable.

The smarter AI gets, the more we need to question it, this is not because it isn’t useful, but because staying in control matters when invisible algorithms start making choices for us. We can protect ourselves and reclaim our agency.

How Does ChatGPT Really Make Decisions? It’s Not Thinking — It’s Predicting.

ChatGPT gives the impression of being a knowledgeable and quick-thinking digital assistant. It produces fluent, natural responses that often make it seem like it truly understands what you’re asking. But in reality, it doesn’t “think” the way we assume. What it relies on are language patterns drawn from massive amounts of data—and those patterns often carry embedded biases and stereotypes (Crawford, 2021).

To put it simply, ChatGPT isn’t figuring out what you actually need; it’s just predicting the next most likely word based on what you’ve typed. For example, if you ask, “Can you recommend an easy dessert?” it pulls from the countless recipes, forum posts, and food blogs it’s been trained on and notices that “tiramisu” comes up more frequently than “brownies.” So that’s what it suggests. It doesn’t know if you own an oven or whether you’re allergic to chocolate. It’s not understanding—it’s guessing. Its accuracy comes not from insight, but from probability and algorithmic refinement.

The bigger issue is the source of that data. It comes from the internet, a space filled with useful knowledge but also with outdated beliefs, misinformation, and social biases. ChatGPT can’t tell the difference. It just pieces together whatever sounds most like an answer and delivers it in a tone that feels confident and convincing. As Safiya Noble (2018) points out, AI systems inevitably absorb and reproduce the structural inequalities embedded in the data they’re trained on, and even when they appear objective.

So, what we’re dealing with isn’t an AI that understands us, it’s a system that is simply very good at sounding like it does. And if we don’t understand how it actually works, it becomes far too easy to mistake it for an expert and trust it more than we should.

Invisible Biases and Real-World Harms

It is easy to trust ChatGPT. It sounds confident, fluent, and even smart. But that polished tone can be misleading. These systems are trained on huge amounts of internet content, which also means they absorb everything the internet carries: stereotypes, misinformation, and long-standing social biases. And these aren’t just theoretical concerns. They show up in ways that affect real people, often subtly but with real harm.

What’s even more concerning is how natural it all feels. If ChatGPT gives you a wrong or biased answer, you might not even notice. Take a student doing research, for instance. If ChatGPT provides incorrect dates or misleading historical information, and the student doesn’t verify it, that misinformation can quietly make its way into assignments or exam prep. But who’s responsible when that happens? Right now, it’s unclear. The system doesn’t explain itself, and there are no solid rules about who is accountable for what it says.

Safiya Noble discusses this in Algorithms of Oppression. One of her examples is particularly striking: while researching Black feminism, she searched “Black girls” on Google and found that the top results were mostly explicit or pornographic. This wasn’t due to her search history. The algorithm simply prioritized what was most clicked, not what was most accurate or appropriate. As Noble (2018, p. 19) puts it, algorithms often surface harmful content not by accident, but because it drives clicks and clicks mean profit.

“Racism and sexism don’t just exist online. They’re profitable.” — Safiya Noble

ChatGPT doesn’t operate in exactly the same way as Google Search, but it inherits many of the same issues. It doesn’t verify truth; it predicts what seems likely based on past patterns. So if its training data frequently links “leaders” with men and “nurturing” with women, it will reflect that language. Not because the AI intends to be biased, but because it simply follows the patterns it has learned.

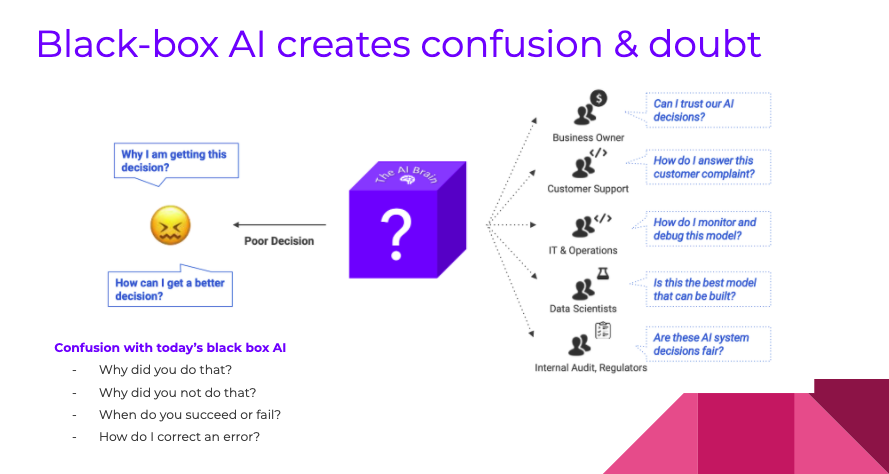

This becomes even more difficult when users aren’t given any real insight into how these answers are generated. You can’t ask ChatGPT, “Where did you get that?” and expect a clear explanation. As Kate Crawford puts it in The Atlas of AI, artificial intelligence isn’t just a technical tool which is a system of power. It reflects the values of those who design and control it, even if those values remain hidden. (Crawford, 2021)

These aren’t glitches or quirks of early-stage technology. They are systemic features. When AI repeats stereotype or reinforces harmful assumptions, it’s not just mirroring society—it’s shaping it. It quietly tells us what’s “normal,” and it does so with a calm, authoritative voice that’s easy to believe. That’s exactly why we need to stay critical, even when the answer sounds right.

Case Study: Academic Integrity Crisis in Australian Universities (2024)

In early 2024, a wave of incidents emerged across Australian universities involving students using generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT to complete their assignments. Students submitted essays, discussion posts, and even full research papers that showed clear signs of AI involvement. The situation quickly escalated when several institutions acknowledged that their existing plagiarism detection systems were unable to reliably identify AI-generated content. The media soon labelled the phenomenon an “academic integrity crisis.”

What made the situation even more complex was the confusion felt by students themselves. Many were unsure whether using ChatGPT actually constituted cheating, especially given that most university policies did not yet clearly address the use of AI. A report by ABC News in February 2024 revealed that some institutions only issued AI-use guidelines months after the crisis began, while others released contradictory or unenforceable rules.

In response, some universities scrambled to revise their academic integrity policies mid-semester. The University of Sydney, for example, introduced new rules stating that using generative AI without proper disclosure would be treated as a violation of academic integrity. However, these changes came too late, and many students had already submitted their assignments under outdated or unclear policies. The inconsistency between institutions only further eroded students’ trust in how AI-related misconduct was being handled.

At the same time, some educators began calling for a more forward-thinking approach: rather than simply banning AI tools, why not teach students how to critically understand and use them? They argued that AI literacy should be incorporated into the curriculum itself. This crisis forced universities to confront a deeper and more urgent question: In an age when machines can generate an essay in seconds, what does “original thought” really mean?

This case highlights a structural issue at the heart of AI governance: our educational and institutional systems are not equipped to keep up with the rapid expansion of generative AI. As Flew (2021) notes, algorithmic systems are often opaque, commercially protected, and difficult to interpret, even for experts. Combined with the speed of platform innovation, this creates a major challenge for policy and educational frameworks to respond effectively and in time. In this crisis, it was students who bore the consequences. However, the deeper issue lay in the absence of clear governance and the lack of transparency in the technology itself.

Tools like ChatGPT don’t explain how they arrive at an answer. They don’t cite sources or offer disclaimers about uncertainty. Yet they present information in a fluent, confident, and authoritative tone that easily builds trust. As a result, when students use these tools, and whether knowingly or due to confusion, they find themselves in a grey area where the rules are unclear, responsibility is ambiguous, and proper guidance is missing.

This crisis offers a powerful example of what happens when AI quietly integrates into our decision-making processes. The problem isn’t that AI took control. The problem is that we gave it away without realizing it. These students were not acting out of malice. They simply didn’t know where the boundaries were, because no one had clearly defined them. The persuasive tone of ChatGPT, combined with the lack of institutional direction and the opacity of AI platforms, all contributed to a loss of control. In the end, it wasn’t the AI that spun out of control, it was the system that failed to provide oversight.

Reclaiming Agency in the Age of AI

Let’s be clear: AI isn’t going away, and frankly, it shouldn’t. Tools like ChatGPT can be incredibly useful when used responsibly. They help us write faster, brainstorm better, and sometimes even learn in entirely new ways. But convenience should not come at the expense of critical thinking. If we never stop to ask how these tools work, or who benefits when we rely on them, we risk slipping into a future where we’ve quietly given up more control than we realize. What happened in universities wasn’t just a “cheating scandal.” It was a warning sign of what can happen when powerful technologies outpace the systems that are supposed to guide them.

In the long run, the universities and the education system as a whole — need to do more than simply catch students after the fact. Right now, most conversations about AI in education focus on plagiarism and punishment. However, that narrow focus misses a much bigger opportunity: helping students understand how these tools actually work. If we want young people to use AI responsibly, we need to teach them what it means to rely on machine-generated content, where its limits are, and how to question its outputs. AI literacy should be just as fundamental as digital literacy. Students aren’t the root of the problem; rather, they are trying to navigate a system that hasn’t yet caught up.

Of course, responsibility doesn’t stop with schools. The companies that develop these tools, such as OpenAI, must also be accountable for how their products are used. ChatGPT currently functions like a black box. It doesn’t cite sources, rarely indicates uncertainty, and never explains how it arrives at its answers. This kind of design encourages trust without real understanding. Imagine if platforms included confidence scores, citation trails, or even flags for potentially biased content. These features would help users stay informed rather than simply impressed. Transparency shouldn’t be optional, it should be a core part of how these tools are built. When a tool speaks like an expert but conceals how it thinks, we risk outsourcing our judgment without even noticing.

While we’re still figuring out whether using ChatGPT for assignments counts as cheating, the EU is already a few years ahead. Their new AI Act requires tools like ChatGPT to come clean when they’re making things up. Imagine if every AI-generated essay came with a disclaimer, like your Instagram filter:

“Warning: This content is 78% likely to contain made-up historical facts.”

That’s the kind of transparency the EU is pushing for. Meanwhile in Australia, we’re still debating whether AI is just a fad. The EU’s approach isn’t perfect, but at least they’re treating AI like the powerful system it is—not just another app on your phone. Without clear national guidelines, we’re left with fragmented policies, inconsistent enforcement, and widespread confusion about what’s allowed and what’s ethical. Regulation doesn’t have to stifle innovation, but it should at least define the rules of the game.

Ultimately, the solution is not to fear AI, but to understand it. These tools are here to stay, and they will only become more embedded in how we learn, work, and make decisions. That is exactly why we cannot afford to stop asking questions. Who designs these systems? Who benefits from them? And who gets left behind when we place too much trust in them?

We don’t need to reject ChatGPT or generative AI entirely. What we need is to stop treating them as neutral assistants. If we want to stay in control, we must rebuild our habits. That means asking where the answers come from, understanding the limits of prediction, and demanding transparency from those in power. The real danger is not that AI will take over, it is that we may quietly surrender control, and without even realizing it.

Reference

ABC News (Australia). (2023). ChatGPT sparks cheating concerns as universities try to deal with the new technology | ABC News. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwqSw3BPbU4

Ahmad, R. (2020). Practical Explainable AI: Unlocking the black-box and building trustworthy AI systems – AI Time Journal – Artificial Intelligence, Automation, Work and Business. AI Time Journal – Artificial Intelligence, Automation, Work and Business. https://www.aitimejournal.com/practical-explainable-ai-unlocking-the-black-box-and-building-trustworthy-ai-systems-2/24799/

Crawford, Kate (2021) The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 1-21.

Cumming, S., & Matthews, C. (2024). Is using chatgpt for an assignment cheating? It depends who you ask. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-06-20/chatgpt-generative-ai-program-used-school-university-students/103990784

European Commission. (2024). AI Act. European Commission. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 79-86.

Open Universities Australia. (2023). How you should—and shouldn’t—use ChatGPT as a student. Www.open.edu.au. https://www.open.edu.au/advice/insights/ethical-way-to-use-chatgpt-as-a-student

Peterson, M. (2023, May 24). Building a successful social media team: The Importance of human and AI collaboration. True Anthem. https://www.trueanthem.com/the-importance-of-human-and-ai-collaboration/

Noble, Safiya U. (2018) A society, searching. In Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University. pp. 15-63.

Be the first to comment