Have you ever noticed that when you open TikTok, Instagram or Twitter, you can find the content that precisely caters to your interests on the homepage or recommendation page? Is this situation designed by humans or the algorithm? Are we in a more open and diverse information world, or are we trapped in the filter bubbles created by algorithms? In the era of algorithmic governance, it is more important than ever to figure these questions out.

In the data-driven era, you can automatically get the information you are interested in without searching for it yourself. This is actually the power of the algorithm, which has been deeply integrated into our lives and has changed the way we access information. “Algorithms can be improved over time by learning from repeated interactions with users and data how to respond more adequately to their inputs: well-designed algorithms evolve so as to be able to predict the outputs sought by users from the vast data sets they draw upon” (Flew, 2021, p. 108). Every behaviour you do, such as pausing, liking, commenting and saving, etc. is training the algorithm to predict your boundaries of interest more accurately.

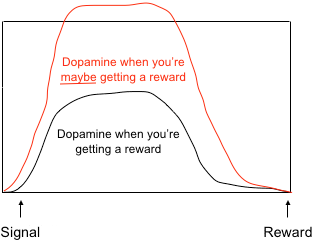

However, for social media platforms, they not only use the algorithm to cater to users, but also incorporate a psychological mechanism in the process. For example, TikTok will not let you easily get what you want. “The platform is highly addictive due to its transmission of content in video format of a short duration based on the Skinner box” (Miranda-Galbe, 2024, p. 270). The psychological strategy of the Skinner Box is intermittent positive reinforcement. After three videos of cats that perfectly match your preferences, the fourth one might be a dance video that you’re not interested in at all. The algorithm pushes content that is valuable to you at random intervals, instead of always satisfying your needs. Because you don’t know when you will see the content you like, you will keep scrolling to find the next surprise. And this is why many people will unknowingly spend hours on TikTok or Twitter. It’s addictive.

“Media industries have typically taken the form of dual markets, as commercial media firms compete in two markets: one for consumer attention, which they try to attract through content, and one for advertiser revenues, where other businesses pay for access to those consumers through their engagement with that content” (Flew, 2021, p. 89). Therefore, the core goal of social media platforms is to take advantage of the algorithm to make users more active and stay longer. Because the longer users stay, the more advertisements the platform can place and the more profit it can make.

Filter bubbles

A video of a couple arguing posted on Douyin (the Chinese version of Tiktok) has caused a public debate. However, it’s not the content itself that has created the heated discussion, it’s the comments section of the video. People were surprised to find that when they saw the comments of the video on male accounts, there were mostly comments from men speaking for men. While on female accounts, they mainly saw comments from women defending women. This makes both sides unable to understand the other’s thoughts. There are countless similar examples. So “the filter bubbles” has become a popular term on the Chinese internet today. Many content creators have started to explain this concept to the public and warn about the dangers of the algorithm. But is this the so-called filter bubbles? Or have we already been trapped by the algorithm in an information bubble where we only hear the voices we like?

According to Pariser (2011, pp. 10-11), filter bubbles are a personalised digital environment created by algorithms. It’s invisible, unchosen, and individualised. And users are unknowingly isolated from diverse perspectives and only exposed to content that reinforces their existing preferences. In other words, the algorithm feeds you what you like, and hides the things that you don’t like. But it’s not transparent. Without your knowledge, the algorithm has removed an opinion that you probably don’t agree with, but that can broaden your horizons.

This personalised recommendation model provides people with a comfort zone. Because there are thousands of new pieces of information on the internet every minute, people will feel powerless when selecting from the multitude of information. So faced with this data tsunami, we instinctively enter the comfort zone provided by algorithms, where we find familiar perspectives, content that conforms to our prejudices. While algorithms have made people more efficient at filtering information, they have also made people lazy. After reading content that interests them, people usually don’t spend time and energy exploring new information. Therefore, this push model makes people worried about whether the algorithm is narrowing our cognitive boundaries while convincing us we’re choosing freely.

How does the algorithm break the filter bubbles? TikTok refugees phenomenon

The TikTok refugees phenomenon in Xiaohongshu in 2025 provides an interesting counterexample. It shows that in some cases the algorithm can promote the spread of diverse information rather than freeze users’ perceptions. Sometimes, you may find that the algorithm will push the content that you have never followed before. It’s because the algorithm is trying to test you to see if it can broaden your range of interests. Because the broader your range of interests, the more content the algorithm can recommend, which will increase the time you spend on the platform.

As TikTok may face a ban in the USA in January 2025, a large number of American users have begun looking for alternative platforms. So many foreign users or “TikTok refugees” have started to use another Chinese social media platform called Xiaohongshu. Xiaohongshu (RedNote) is a content sharing and social commerce platform that combines elements of Instagram, Pinterest, and e-commerce (Concannon, 2024). It focuses on user-generated content, where people share product reviews, lifestyle tips, and other recommendations. The hashtag “TikTok Refugees” has become a trending topic on Xiaohongshu.

This unexpected digital migration offered a chance to break the existing filter bubbles. The content that American users find on TikTok or other traditional media is often limited by their personal interests and habits, or shaped by the values and political positions of the media. However, the content ecology of Xiaohongshu is different. For many people, this is the first time they have been exposed to an unfiltered, original description of China or the United States, instead of the version translated and interpreted by the media. The algorithm of Xiaohongshu was initially designed for Chinese users. But foreign users bring different interests and interaction patterns, where they share their lives, learn Chinese, and interact with Chinese users. After receiving these new data, the algorithm begins to adjust its recommendation strategies to adapt to the interests or necessities of new users. It begins to push more content related to culture, humanities and customs to foreign users to explore their potential interests. At the same time, this also makes more international content appear in the information stream of Chinese users, and many netizens who have never been exposed to this kind of information also receive relevant information.

For example, foreigners must pay a “cat tax” to enter Xiaohongshu. It refers to the trend where foreign users post pet pictures to connect with the Chinese community. And users from different countries start fact-checking each other, which means that they tell each other their opinions and stereotypes about each other’s country or society, and hope that the other person can tell them if their opinions are correct or correct them. When the algorithm notices that cross-cultural interactions such as paying cat taxes or fact-checking are becoming more popular, it interprets this as valuable content. As a result, it will increase the visibility of this type of content and push more similar content with cultural exchange characteristics to a wider group.

This shows that the algorithm is not a static and fixed system but an adaptive one. It will make appropriate adjustments to the recommendation strategy based on popularity of the content and global trends. The diversity of users will also affect the spread of information and break some stereotypes.

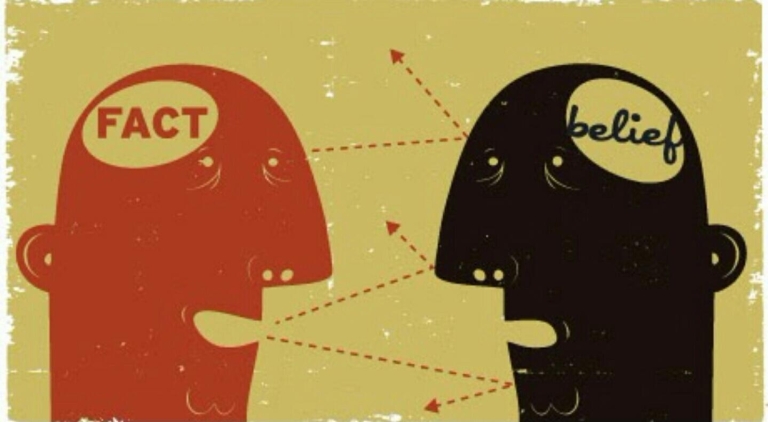

However, even if the algorithm provides diverse information, some users still choose to immerse themselves in their own cognitive framework. They are unwilling to browse information from other countries, and even resist people from other countries using the platform. They are unable to actively accept different points of view. This is the real factor leading to cognitive dilemmas. It’s not the algorithm that determines your world, but how you choose information that determines the world you see.

A dialectical view of the relationship between the algorithm and the filter bubbles

Essentially, personalised recommendations don’t directly cause the filter bubbles. The algorithm is a technical approach designed to improve the user experience. However, when we blame the algorithm for the filter bubbles, we ignore the factor of individual autonomy. Although the algorithm can reinforce biases, users also consciously avoid discomfort. People are trapped in filter bubbles more because they actively filter out information that doesn’t align with their own positions, which creates cognitive bias.

People are more like in an echo chamber, “an environment in which the opinion, political leaning, or belief of users about a topic gets reinforced due to repeated interactions with peers or sources having similar tendencies and attitudes” (Cinelli et al., 2021). It’s not that you don’t hear other sounds, it’s just that you only want to hear familiar sounds.

Human prejudices are more stubborn than the algorithm. As the TikTok Refugees phenomenon shows, when users are finally exposed to the real but possibly uncomfortable world rather than just things they like, misunderstandings, confrontation, avoidance, labelling, etc. still exist. There are not just the filter bubbles, but also the cognitive bubbles that reaffirm your thinking and manipulate you to reject different voices.

How to break out of the filter bubbles? A two-way effort between technology and people

Surveillance capitalism exploits human experience as free data, using machine intelligence to transform it into predictive products that not only monitor but also shape user behavior for profit. (Zuboff, 2019, p. 8)

Although the algorithm may not be the main culprit, algorithmic governance is still important. Digital platform companies still need to manage and regulate algorithmic behaviour. While pursuing commercial interests, they also need to assume their social responsibilities to protect users’ right to be informed and to have autonomy in accessing and choosing content.

Today, some social media platforms have begun to practice algorithmic transparency in order to increase user autonomy. For example, recently Xiaohongshu has announced that its algorithm analyses users’ personal information and behavioural data to tag users and push them personalised content. The platform also provides a “content preference adjustment” function, allowing users to actively manage and optimise their recommended content (Lingkeclub, 2025). Moreover, legal regulations and policies are also gradually advancing and guiding the way, such as the EU’s Digital Services Act, which requires platforms to allow users to turn off personalised recommendations (European Commission, 2024, p. 3).

However, breaking the filter bubbles requires the active participation of users as well. In the process of mutual domestication of humans and algorithms, “users enact algorithmic recommendations as they incorporate them into their daily lives, but these algorithms are designed to adjust to these enactments in order to colonize users” (Siles et al., 2019, p. 19). Users and the algorithm influence each other mutually. The algorithm is constantly adapting to user habits, and users are also shaping the algorithms through their behaviour. Therefore, the digital literacy of the user is crucial, because how to select and interpret the information depends on the initiative of the user.

You can try to click on the content that differs from your opinion to maintain a diversity of information. At the same time, we can also actively use the search function, instead of just passively scrolling down to get information. We need to tell the algorithm that we are willing to learn more. In fact, the process of training the algorithm is also training our own digital literacy. We need to step out of the cognitive comfort zone consciously to resist the influence of algorithmic colonisation. When we take the step to listen to the voices which are different from our own, we can break through the filter bubbles and regain our right to choose information by ourselves freely.

Conclusion

We are living in an era that is deeply influenced by the algorithm. It improves the user experience and increases the commercial profits of the platform. But at the same time, the algorithm is also quietly changing the way we see the world. The information flow that is designed for us unconsciously shapes our cognitive structure, and we may even be trapped in the filter bubbles, and this narrows our horizons.

However, the case of the TikTok refugees tells us that this risk is not inevitable. When the user base and interaction patterns of a platform change, the algorithm will also adjust and adapt accordingly. As new users join and cross-cultural interactions increase a lot, the algorithm begins to push more relevant content, which has helped groups that were previously isolated to communicate with each other. This change shows us that there is actually a chance to break the filter bubbles. But the key to solving problems isn’t just the algorithm. The algorithm filters and pushes information based on our interests. Therefore, it cannot decide what we can see by itself. But breaking the filter bubbles doesn’t mean we have to give up our personal interests. Instead, what we need to do is learn to look more, explore more. Because maybe the topic you didn’t care about before can bring new perspectives and insights. If we continue to avoid content that challenges our beliefs, we will only get deeper and deeper into the trap we have created for ourselves. The information world doesn’t lack diversity, what it lacks is our initiative to take the first step. It is our own choice that makes us stuck in the filter bubbles. We need to make the algorithm a tool, not a cage, and this is the digital literacy we really need.

References

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Concannon, L. (2024, May 8). What is Little Red Book (Xiaohongshu)? Meltwater. https://www.meltwater.com/en/blog/little-red-book-xiaohongshu

European Commission. (2024, February 23). Questions and answers on the Digital Services Act. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_2348

Flew, Terry (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, Chapter 2, pp. 41-72.

Lingkeclub. (2025, February 06). Xiaohongshu’s recommendation algorithm revealed! Is the algorithm the same as you think? Zhihu Column. https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/21600566314

Miranda Galbe, J. (2024) “Perception of journalism students regarding TikTok as an informative tool”, VISUAL REVIEW. International Visual Culture Review / Revista Internacional de Cultura Visual, 16(3), pp. 267–278. doi: 10.62161/revvisual.v16.5265.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press.

Siles, I., Espinoza-Rojas, J., Naranjo, A., & Tristán, M. F. (2019). The mutual domestication of users and algorithmic recommendations on Netflix. Communication Culture and Critique. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz025

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: Public Affairs.

Be the first to comment