In this era, smart devices have brought convenience into our homes. Picture this, when you wake up in the morning and request your smart device to do something for you.

For instance, you ask your smart speaker to play your favorite morning playlist or request your thermostat to adjust your house temperature as well as request your coffee maker to warm some coffee for your morning quench. It is evident that smart devices are bringing automated convenience to your home and it feels like you are living in the future.

The uncomfortable truth is that your smart devices are ever watching you even in times you think they are not in use. But, do you ever question yourself, at what cost?

These smart devices are supported by Internet of Things (IoT). Well, what is IoT? IoT is a network of physical devices or objects such as appliances, vehicles, and any other that are embedded with network connectivity, sensors, or software to collect and share data (ibm.com, 2023).

The explosive growth of IoT is a technological revolution that has transformed lives making it more convenient while creating a sprawling landscape of vulnerabilities to privacy and digital rights concerns. From sensors to voice assistants to smart TVs which record private conversations and track habits are always surveillance tools in many homes.

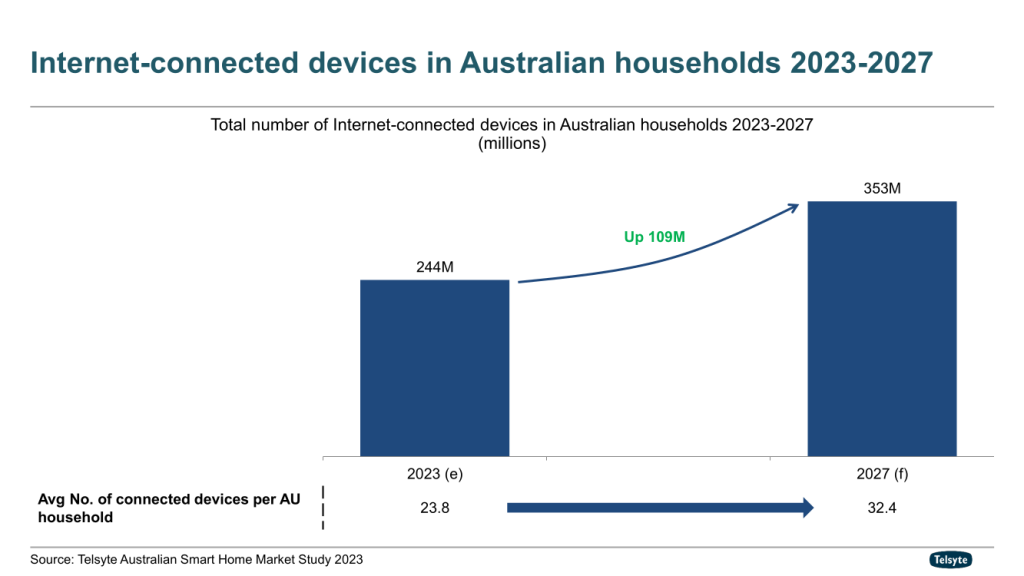

The Financial Review reports that 7.6 million Australian homes have at least one smart device installed while 3 million have at least five smart home devices by the end of 2023 (Davidson, 2024). Statistics indicate a significant increase in number of smart device users by 2027. According to Telsyte forecast, the number of smart device users in Australia is expected to grow by nearly half by 2027.

Courtesy of: Telsyte (2024)

Despite the growing market for smart devices in Australia, the privacy concerns of IoT are yet to be addressed. IoT issues and concerns go beyond consumer and privacy law as well as technical standards of information security (Harkin, 2022).

The convenience that comes with smart devices might be unknowingly trading our private conversations. Let’s pull back and understand what is happening in our smart homes.

The pervasive privacy concerns with IoT devices

The tension between functionality and surveillance is the IoT privacy concern (Chanal & Kakkasageri, 2020). These devices are designed to continuously gather vast amounts of data to improve their performance and provide personalized experiences, but this data collection often extends far beyond what users reasonably expect or knowingly consent to.

Consider smart speakers like Amazon Alexa or Google Home: while users understand these devices listen for “wake” words, many don’t realize they frequently record and store conversations that occur near them, even when not deliberately activated. These recordings can be personal conversations and when shared on these platforms are stored on corporate servers which can be accessed by other employees or even hacked.

The privacy issues are more concerning when one looks at the entire smart home environment that is currently prevalent in homes today. Smart TVs do not only record what TV programs you are watching; many models contain ACR technology which is an automated content recognition technology that records everything on the screen, including private photos, documents, or surveillance cameras (Varmarken et al., 2020).

Fitness trackers and smartwatches collect all sorts of data that may include information ranging from how the user sleeps to what could be a health ailment. Modern fridges, washing machines, or even light bulbs monitor their use and interaction with the residents in ways that would not have been possible even a decade ago.

Your smart home devices can spy

One of the most striking examples of the privacy concerns of IoT devices was the case of a murder that occurred in Hallandale Beach, Florida in 2019 (Howell, 2020). Prosecutors wanted to obtain recordings from an Amazon Echo that was present at the time of the crime, believing that the device might have recorded the crime even if the ‘Alexa’ feature was not intentionally activated (Howell, 2020). Although Amazon initially did not want to share the data with the authorities stating privacy issues involved in it, the case pointed out several unpleasant truths about the IoT devices in our homes.

First, it showed that such devices are always analyzing audio data, even when we think they are not in use (Howell, 2020). Second, it proved that police forces around the world have started to consider smart home devices as potential sources of evidence, which some legal scholars called a “de facto surveillance network” that is run by people who are not aware of it (Howell, 2020). Most disturbingly, the case demonstrated how the boundary between a helpful home assistant and an unsuspected spy can complicate our notions of privacy and consent.

This incident was not isolated. Other similar incidents have been witnessed where Fitbit data was used to refute alibi, where smart thermostat records were used to set timeline in investigations, and where Ring doorbell footage was shared with the police without the user’s consent (McClaran, 2021). These cases combined give a picture of a future where the gadgets that we have welcomed into our homes may be used against us in ways that were never foreseen.

Who is really benefiting from your smart home device?

Behind the curtain of smart home technology, there is a hidden and rather opaque data industry in which the most valuable asset is information about people (Lipford et al., 2022). Technology industries generally present data gathering as a process for enhancing products and services, but it is much more complex and sinister. Most IoT manufacturers work on a business model that is not the device itself but the real product is your data.

This is particularly worrying due to the opaqueness in this system. The majority of IoT privacy policies are filled with legal language that only serves to hide the nature of the data collected and its use (Goggin et al., 2017). A study that was conducted in 2022 showed that the average smart device communicates with various third parties including advertisers, data brokers, and cloud service providers among others (Oh et al., 2020).

This is what privacy experts refer to as a ‘data supply chain’ where details about your day to day activities, health, and even what you discuss with your close ones may go through several ownership before being utilized in ways you never signed up for (Oh et al., 2020).

These advancements have been accompanied by a lack of proper regulation by the authorities (Lipford et al., 2022). To some extent, GDPR can be implemented in different countries, but most of them do not have specific laws on IoT devices (Barati et al., 2020). For instance, in the United States, there is no federal law on privacy and consumers rely on state laws with huge gaps when it comes to connected devices.

Perhaps most worrying is the use of data collected by IoT devices for purposes other than advertising, which is the traditional use of the collected data. Insurance companies have considered the possibility of using smart home data to set premiums, employers have thought about using wellness trackers for tracking workers, and the police have signed contracts with device manufacturers for easier access to users’ data (Joh & Joo, 2022). This creates a world where the conveniences of smart technology could potentially be used to limit opportunities, increase costs, or even facilitate discrimination based on data most people don’t realize is being collected.

The regulatory gap

Despite growing concerns, legislation struggles to keep pace with IoT development. Australia’s Privacy Act amendments proposed in 2023 would strengthen consent requirements for data collection, but many IoT devices use interface designs that make meaningful consent nearly impossible (Gupta., 2023).

The European Union’s Digital Services Act, fully implemented in 2024, requires device manufacturers to clearly disclose all data practices before purchase and minimize collection (Bradford, 2023). However, some IoT devices still fail to comply with these requirements.

Your convenience at what cost?

As we stand at the crossroads of technological innovation and personal privacy, society faces critical questions about the kind of digital future we want to create. The current trajectory of IoT development suggests a world where convenience increasingly comes at the cost of privacy, where our homes are filled with devices that know more about us than we might know ourselves, and where this intimate knowledge is monetized by corporations and potentially accessible to governments.

Some technologists argue this is simply the inevitable price of progress, and that the benefits of connected devices outweigh their privacy costs. Others warn we’re sleepwalking into a surveillance society where the very concept of private life is eroded by the technologies we willingly invite into our homes (Suzor, 2019). The truth likely lies somewhere in between, but the window for establishing meaningful protections and boundaries is closing as these technologies become more entrenched in our daily lives.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether we should embrace or reject smart technology, but rather how we can shape its development to respect fundamental privacy rights while still delivering innovative services (Flew, 2021). This will need the cooperation of the consumer, the technologist, and the policy maker to develop such frameworks that will place the people above the dollar and privacy above convenience.

Can you reclaim your control?

It’s a question that becomes more pertinent as our homes become more connected, and that is whether or not the most private spaces in our lives should be the profitable spaces for data gathering?

Although, the privacy risks associated with IoT devices are real, there are measures that consumers can take to enhance their security in the growing connected environment. The first and the foremost is to acquire what digital rights activists refer to as device literacy (Sadhu et al., 2022), That is, spend the time to find out what data each of your smart devices gather and how this information is processed.

The first step is to properly go through the privacy options on all the devices that are connected to the internet (Sadhu et al., 2022). Unfortunately, the default security settings of many IoT products are quite liberal with the data collected, rather than the privacy of the users. Turn off unused functions that are connected to microphones or cameras that may be constantly active. In voice assistants, check for voice history and get in the habit of deleting it, and for sensitive conversations, turn on the mute function.

Network security is another factor of protection that is of great importance. Isolate IoT devices from other networks such as the computer and smartphone networks to reduce the number of entry points that hackers can use (Sadhu et al., 2022). Always create and employ complicated and different passwords for all the devices and enable two-factor authentication where possible. One should consider buying a network-level ad blocker or firewall that would prevent the data from being transmitted to third parties.

On a broader societal level, supporting organizations and policies that advocate for stronger IoT privacy regulations can help create systemic change (Lipford et al., 2022). The current market provides few incentives for companies to prioritize privacy over data collection, meaning meaningful change will likely require legislative action. Consumers can make their voices heard by supporting digital rights organizations, contacting elected representatives about privacy concerns, and choosing products from companies with demonstrably better privacy practices when possible.

Remember, you can make informed choices

A Sydney resident, switched to local-processing alternatives after discovering her smart speaker had recorded several private arguments. “The convenience wasn’t worth the constant feeling of being watched,” she says. “I still use smart technology, but now I know exactly what information leaves my home.”

What are your thoughts? Are you comfortable with the current trade-offs between smart home convenience and personal privacy? Have you taken steps to secure your IoT devices, or do you feel the risks are overblown? Share your experiences and perspectives in the comments – because in an era of constant data collection, having these conversations might be one of the most important ways to protect our digital futures.

Reference List

Barati, M., Rana, O., Petri, I., & Theodorakopoulos, G. (2020). GDPR compliance verification in internet of things. IEEE access, 8, 119697-119709. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/iel7/6287639/8948470/09127459.pdf

Bradford, A. (2023). Europe’s Digital Constitution. Va. J. Int’l L., 64, 1. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm?abstractid=4599308

Chanal, P. M., & Kakkasageri, M. S. (2020). Security and privacy in IoT: a survey. Wireless Personal Communications, 115(2), 1667-1693. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Poornima-Chanal/publication/343316979_Security_and_Privacy_in_IoT_A_Survey/links/630cb93761e4553b9549cf0d/Security-and-Privacy-in-IoT-A-Survey.pdf

Davidson, J. (2024). Smart Home Gadget Sales Rise Despite Privacy, Cost-of-Living Worries. Financial Review Report. Retrieved from: https://www.afr.com/technology/smart-home-gadget-sales-rise-despite-privacy-cost-of-living-worries-20240315-p5fcs1

Flew, T. (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.2

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., & Bailo, F. (2017). Digital Rights in Australia. Retrieved from: https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/17587/USYDDigitalRightsAustraliareport.pdf?sequence=7

Gupta, C. (2023). Submission to the Attorney-General–Privacy Act Review Report. http://www.cprc-sf.org/pdf/cprc-submission-privacy-act-review-report-march-2023.pdf

Harkin, D., Mann, M., & Warren, I. (2022). Consumer IoT and its under-regulation: Findings from an Australian study. Policy & Internet, 14, 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.285

Howell, L. C. (2020). Alexa Hears with Her Little Ears-But Does She Have the Privilege? Mary’s LJ, 52, 837. Retrieved from: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1117&context=thestmaryslawjournal

IBM Website (ibm.com). (2023). What is the Internet of Things? Retrieved from: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/internet-of-things

Joh, E., & Joo, T. (2022). The harms of police surveillance technology monopolies. In Denver Law Review Forum (Vol. 99, No. 1, p. 1). https://digitalcommons.du.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1213&context=dlrforum

Lipford, H. R., Tabassum, M., Bahirat, P., Yao, Y., & Knijnenburg, B. P. (2022). Privacy and the Internet of Things. Modern Socio-Technical Perspectives on Privacy, 233. Retrieved from: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/52825/978-3-030-82786-1.pdf?sequence=1#page=235

McClaran, N. (2021). The Opportunities and Challenges of Internet of Things Evidence in Regard to Criminal Investigations. Retrieved from: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=honors-theses

Oh, H., Park, S., Lee, G. M., Choi, J. K., & Noh, S. (2020). Competitive data trading model with privacy valuation for multiple stakeholders in IoT data markets. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(4), 3623-3639. Retrieved from: http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/12228/1/IEEE_IoTJ_Camera_Ready.pdf

Sadhu, P. K., Yanambaka, V. P., & Abdelgawad, A. (2022). Internet of things: Security and solutions survey. Sensors, 22(19), 7433. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/19/7433

Suzor, N. P. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.3.

Telsyte. (2024). Australia’s Smart Home Market Set to Crack $2.5, Driven by AI, Energy Savings and Security. Retrieved from: https://www.telsyte.com.au/announcements/2024/3/20/australias-smart-home-market-set-to-crack-25b-driven-by-ai-energy-savings-and-security

Varmarken, J., Le, H., Shuba, A., Markopoulou, A., & Shafiq, Z. (2020). The TV is smart and full of trackers: Measuring smart TV advertising and tracking. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies. https://petsymposium.org/popets/2020/popets-2020-0021.pdf

Be the first to comment