The invention of the machine at the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s disrupted many industries and birthed capitalism as we know it today. Prior to this economic development, the production of goods heavily relied on manual labor and the hand. The invention of the water wheel and the steam engine signaled the transition of agrarian and rural societies to urbanization. Soon, artisans and skilled workers found themselves displaced out of their jobs and replaced by machines.

Technology and machine automation has changed the way people work. With the recent resurgence of artificial intelligence, how will this affect the labor market?

In the early 19th century, the textile industry was gaining fast momentum generated by power looms and the mechanization of wool and cotton production. Unemployment rose and wages were reduced, that led to the industrial protest called the “Luddite riots.” Furious workers broke into factories and destroyed textile machinery. It became a national threat that troops were deployed to defend production facilities.

As more machines were invented, automation anxiety among workers persisted through the 20th century. New and existing industries expanded, and mass production flourished with the invention of electricity. While workers expressed their displeasure over being replaced by machines, others saw this as a boon rather than a bane to society. A New York Times article from April 8, 1955 was published with the headline “Automation Puts Industry on Eve of a Fantastic Robot Era.” Reporter A.H. Raskin writes, “[Automation] promises a vast expansion in goods and services, sharp reduction in prices and increased opportunity for the enjoyment of leisure. It makes the three-day weekend a realizable goal; it offers emancipation from the drudgery of routine, repetitive tasks.”

Today, technology is accelerating faster than human comprehension. Machines can not only automate manual labor, but also perform cognitive tasks. Artificial intelligence has been fully integrated to everyday life, used as tools to simplify and improve standards of living. Established data infrastructures are shaping civil society (Kitchin, 2014). Algorithmic systems are altering human production and consumption. Recent breakthroughs like ChatGPT and Midjourney have showcased how far human intellect and creativity has come. Effects of advanced technology has spread like wildfire across civilization and will continue to impact future generations.

Technology and machine automation has changed the way people work. With the recent resurgence of artificial intelligence, how will this affect the labor market? Is AI coming for your job?

The Thinking Machine

Can machines think? This was a question raised by British computer scientist, Alan Turing on his thought-provoking essay published in 1950. Turing posited the potential of computers to think and behave intelligently, much like a human could. It also included a proposal of the Turing test, an experiment that determines a computer’s ability to formulate humanlike responses. Turing’s paper set a precedent on the literature and philosophy of artificial intelligence in the decades to come.

Artificial intelligence gradually picked up its pace in the 1950s, as several AI labs were established in different educational institutions. These laboratories were dedicated spaces for machine learning research. Soon, machines were able to play chess, solve problems, process and interpret natural language, and recognize speech. During this period, artificial intelligence was centered on building anthropomorphic machines that automated labor tasks and mimicked human cognitive abilities. It seemed like a page out of a science fiction novel, set in research labs and factories, inaccessible to the ordinary person. Now, AI can fit in our pockets.

Artificial intelligence in the 21st century

The new generation of AI rose in the 21st century, as machine learning developed and advanced. Big data, algorithms, and hardware are the main drivers of artificial intelligence (Megorskaya, 2022).

Now, AI is deeply embedded in the life of the average modern man. It may go unnoticed–almost invisible, but its absence will be felt. From the GPS that takes you to work, FaceID, voice-automated assistants like Alexa and Siri, smart home devices, to the shows recommended by Netflix, AI performs almost automatically that it functions like a general-purpose technology (Elliott, 2019).

The One Hundred Year Study of Artificial Intelligence or AI100 is a study written in collaboration of multiple experts in AI research. Hosted by Stanford University, it aims to track and forecast developments in artificial intelligence and how it affects society across all aspects. The latest report published in 2021 noted that machine learning has moved from academic research to real world applications, not just in daily life but in major sectors like health and finance. Neural network language models have been developed to support machine translation, text classification, speech recognition, writing aids, and chatbots (AI100 Report, 2021).

Renewed interest in AI and its potential for economic growth rekindled funding initiatives in research and development. Stanford HAI’s Artificial Intelligence Index 2021 reports an increase in global corporate investment of 40 percent just from 2019 to 2020 alone. By 2025, AI investments in the European Union will reach €22.4 billion (Fullerton, 2021). And at the forefront of the funding race is generative AI technology.

Resurgence of Generative AI

In November 2022, OpenAI, an American AI research laboratory, released ChatGPT. GPT stands for Generative Pretrained Transformer. This Microsoft-backed free chatbot can apparently understand and answer complex questions with human-like coherence. In only five days, over a million curious people signed up test it out. Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence powered by large language models (LLMs) that can create content like images, texts, code, audio, and even art. This type of LLM is fed large volumes of datasets (mostly public online data), trained to recognise and analyse patterns, and predict responses for prompts (Routley, 2023.)

Since ChatGPT’s viral release, multiple tech companies came out with their own chatbots. Microsoft’s Bing and Google’s Bard are among others that are trying to challenge ChatGPT. Image-generators like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion also entered the mainstream, fascinating users with rendering lifelike images based on text prompts. GPT-4, ChatGPT’s latest model, was launched in March 2023. In a span of months, it seems like tech giants are trying to outperform each other. The race to AI has never been this close.

An open letter signed by more than 1,000 tech luminaries and researchers called to pause AI developments in the next six months. It came as a warning that “human-competitive intelligence can pose profound risks to society and humanity.” The fear of the speed of the expansion of artificial intelligence has been raised by critics for years. But concerns have ramped up recently as generative AI platforms have found to be possible breeding grounds for misinformation and discrimination. Meta’s LLM Galactica, was shut down only three days following its deployment after it was discovered to generate biased and inaccurate information, an occurrence in AI that is referred to as “hallucinations.”

Even so, AI’s generative possibilities are endless and unpredictable. For the average person, it can summarise your to-do list, make meal plans, or organise a travel itinerary. But for professionals, the effects can be profound. Teachers are worried students might turn in AI-generated essays, artists are concerned about copyright violations, and office workers are troubled that AI will render them jobless. OpenAI has started collaborating with different organisations and have opened API access for developers and businesses. In fact, several companies have already begun integrating artificial intelligence in their workplaces. International law firm Allen & Overy (A&O) has released a ChatGPT-backed chatbot to assist its employees in day-to-day legal work. If this trend continues, how will this eventually affect the labor market and the welfare of the workers?

AI and the Labor Market

Since the Industrial Revolution, job automation has not ceased. And it looks like it’s not slowing down anytime soon. In 2013, a study from the University of Oxford estimated that 47 percent of jobs in the United States could be impacted by computerisation in the next decade or two (Frey, C. & Osborne, M., 2013). Seven years later, COVID-19 has completely disrupted the workplace, with accelerated efforts of automation and digitisation. The World Economic Forum reports that by 2025, 85 million jobs globally will be affected by these technological changes. While human skills will still be essential, information and data processing and administrative tasks will most likely be augmented to machines.

Early research shows that large language models (LLMs) have the potential to alter occupations in countries like the United States. Roughly 80 percent of the workforce could have 10 percent of their tasks impacted by programs like ChatGPT (Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P., & Rock, D., 2023). This forecast of disruption causes employment anxiety among workers. With the speed and scale of these developments, it looks like the destabilisation of the labor market will come sooner than imagined. There are people who fear for new technologies affecting their workplace, resulting in anxiety and financial insecurity (McClure, 2018). The replacement of human labor at a reduced cost could also affect workers (AI100 Report, 2021).

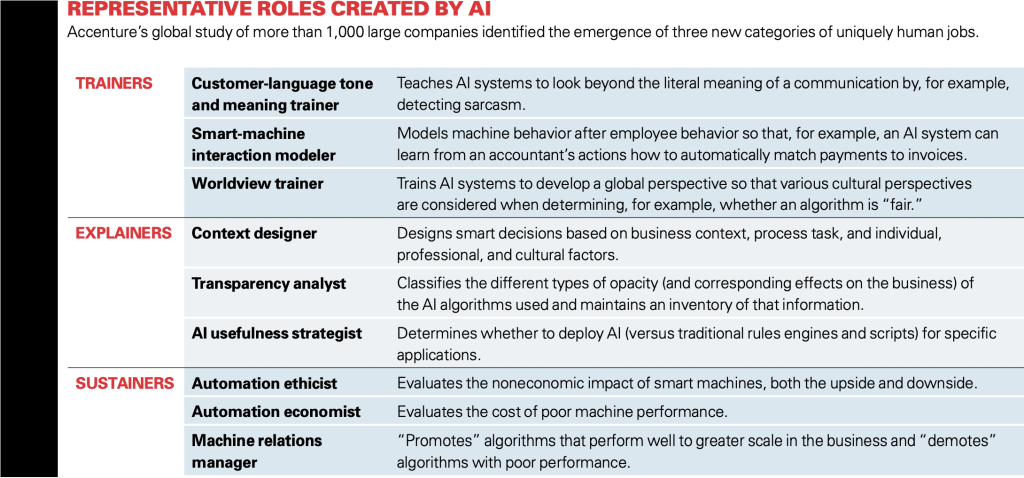

On the other hand, optimists view artificial intelligence as one of the keys that could unlock global productivity growth. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, tells ABC News that AI is “a tool for humans, an amplifier for humans.” AI could increase productivity and create new job categories and industries. And while it could replace occupations, it will eventually create new opportunities (Wilson, H. J., Daugherty, P., & Bianzino, N., 2017). Artificial intelligence will force companies to revisit business processes and internal organizations. Researchers from Accenture have identified new types of human occupations that will be essential to further advances in artificial intelligence. The study also notes that most of these jobs will likely require advanced degrees and highly specialised skillsets. This may create an employment gap between blue-collar and white-collar workers.

It is also important to consider that artificial intelligence requires huge monetary investments and massive volumes of data and processing power. Realistically, it is only accessible to large companies in developed countries. Economic productivity will be unevenly felt (Hirsch, 2019). This could lead to an even greater global digital divide.

To date, AI governance systems are not in place, with the technology having little to no regulation. Like most online platforms, private companies like OpenAI are self-regulated. However, with the looming impacts of AI across global industries, this may not be enough. Aside from ramping up internal regulation efforts, companies should collaborate with expert organizations that will closely audit, monitor, and dedicate research of the technology. In 2016, the Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence was formed by academics researching AI safety methods. This UC Berkeley-led research group aims to develop AI systems that will benefit humanity instead of corporate interests. Independent organizations like CHAI should be supported and well-funded. Further, companies should also cooperate with governments to establish public policies that will legally protect employment and guide workers as they transition, such as providing upskilling programs.

The Future of AI

There seems to be a current trend in tech companies trying to beat each other with the latest generative AI capabilities. As most of these companies are funded by private corporations, there are growing concerns that they will put profit above anything else (ChatGPT Plus charges a monthly fee of $20 per user while a Midjourney Basic Monthly Plan costs $10.)

The call to slow down AI developments come at a crucial time. Society is standing at a crossroads of change brought about by technological disruptions. If left unsupervised and unregulated, it could overwhelm several industries–from labor to politics to education. Ample time should be given to process and comprehend the technology and see how different sectors can adapt to these changes. Similarly, while governments are notorious in regulation, policymakers should also step in. Generative AI seems to be in the middle of a renaissance. Whether or not tech companies will heed the advice for a pause, the next few months will be pivotal in the future of AI.

The possibility of generative artificial intelligence as a ubiquitous tool for humans seems to be getting warmer and warmer. At this rate, it seems to be a double-edged sword. Like all new technologies, its reception is met by advocates and alarmists alike. But one thing is clear, AI should be developed responsibly. Companies should be held accountable, and transparency should be at the forefront of their mission. Regulation should not be done only to avoid legal liabilities, but also to protect society from possible harms. Misinformation, data privacy concerns, and hate speech are enough evidence that current technological structures can be weak and vulnerable to misuse. Embedding diversity, ethics, and transparency in new technologies could make for an effective and reliable use. By designing AI to be human-centered, society can properly adapt and benefit from it.

References

ABC News. (2023, March 18). OpenAI CEO, CTO on risks and how AI will reshape society. [Video]. YouTube.

Anyoha, R. (2017, August 28). The History of Artificial Intelligence. Science in the News, Harvard University. https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/history-artificial-intelligence/

Basham, V. (2023, February 16). Allen & Overy integrates ChatGPT-style chatbot to boost legal work. The Global Legal Post. https://www.globallegalpost.com/news/allen-overy-integrates-chatgpt-style-chatbot-to-boost-legal-work-1735539269

Buchanan, B. G. (2005). A (Very) Brief History of Artificial Intelligence. AI Magazine, 26(4), 53. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v26i4.1848

Chowdhury, R. (2023, April 6). AI Desperately Needs Global Oversight. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/ai-desperately-needs-global-oversight/

Elliott, A. (2019). The Culture of AI: Everyday Life and the Digital Revolution. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P., & Rock, D. (2023). Gpts are gpts: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.10130

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?. Technological forecasting and social change, 114, 254-280.

Fullerton, K. (2021, October 18). New AI Watch report: 2020 EU AI investments. European Union. https://futurium.ec.europa.eu/en/european-ai-alliance/blog/new-ai-watch-report-2020-eu-ai-investments

Future of Life Institute. (2023, March 22). Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter. https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

Hirsch, Jeffrey M., Future Work (February 14, 2019). University of Illinois Law Review, 2020 Forthcoming, UNC Legal Studies Research Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3334667.

Kitchin, R. (2014). The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications.

Littman, M. L., Ajunwa, I., Berger, G., Boutilier, C., Currie, M., Doshi-Velez, F., … & Walsh, T. (2022). Gathering strength, gathering storms: The one hundred year study on artificial intelligence (AI100) 2021 study panel report. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.15767.

McClure, P. K. (2018). “You’re Fired,” Says the Robot: The Rise of Automation in the Workplace, Technophobes, and Fears of Unemployment. Social Science Computer Review, 36(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317698637.

McKinsey & Company. (2023, January 19). What is Generative AI? https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-generative-ai

Megorskaya, O. (2022, June 27). Training Data: The Overlooked Problem Of Modern AI. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2022/06/27/training-data-the-overlooked-problem-of-modern-ai/?sh=5cbf89a9218b

National Geographic Education. (Undated). Industrialization, Labor, and Life. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/industrialization-labor-and-life/

Raskin, A.H. (1955, April 8). Automation Puts Industry on Eve of Fantastic Robot Era. The New York Times. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1955/04/08/93801127.html?pageNumber=14

Roose, K. (2023, February 3). How ChatGPT Kicked Off an A.I. Arms Race. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/03/technology/chatgpt-openai-artificial-intelligence.html?smid=url-share

Routley, N. (2023, February 6). What is generative AI? An AI explains. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/generative-ai-explain-algorithms-work/

Russo, A. (2020, October 20). Recession and Automation Changes Our Future of Work, But There are Jobs Coming, Report Says. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/10/recession-and-automation-changes-our-future-of-work-but-there-are-jobs-coming-report-says-52c5162fce/

Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. (2021). Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2021. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-AI-Index-Report_Master.pdf

Wilson, H. J., Daugherty, P., & Bianzino, N. (2017). The jobs that artificial intelligence will create. MIT Sloan Management Review, 58(4), 14.

Be the first to comment