Introduction

In today’s digital age, the Internet has become part of our daily lives. Every day we wake up and use our mobile phones or laptops to communicate, study, work or fill our leisure time, all these operations are inseparable from the Internet. But just like every coin has two sides, the Internet brings us convenience but also hides a lot of dangers and harms such as cyber violence, malicious attacks and speech which we have heard a lot about. These ‘electronic garbage’ not only pollutes the online environment but also may cause discrimination, conflict and violence in reality society.

From Facebook, Twitter to WeChat, and other social platforms around the world, each platform has been experimenting with different approaches to platform governance and moderation. Some have been criticized for strictly deleting posts and restricting freedom of speech, while others have been criticized for being lazy and ignored, leading to a proliferation of problems.

This article will talk about the causes and effects of hate speech, as well as the case study of Meta’s changes on censorship, to see if we can find a balanced method to make the Internet both free and safe for every user.

Definition of hate speech

In most instances, hate speech is recognised as regulable in international human rights law and in the domestic laws of most liberal democracies. To be regulated, hate speech must harm its target to a sufficient degree to warrant regulation. So knowing the definition of hate speech is very crucial for the prerequisite of the hate speech regulation.

Hate speech has been defined as speech that ‘expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation’ (Parekh, 2012, p. 40)

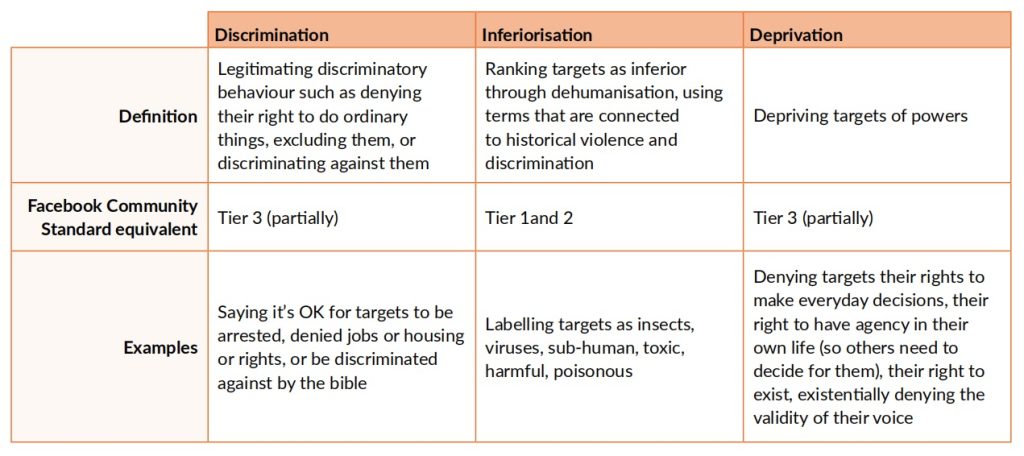

There is the three tiers defined in Facebook, 2020 Community Standards, Objectionable Content: Hate Speech.

Source: Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific. P12

Firstly, the speech must be posted to a ‘public’ platform, where it is possible for other users to be inadvertently exposed to it. In other words, purely private conversations or messages should not be surveilled and regulated. On Facebook, for instance, anything other than purely private conversations or ‘direct messages’ can be regulated as ‘public speech’. (Sinpeng, P11)

Secondly, speech must target systemically marginalised groups in the social and political environment. Non-systemically marginalised groups (most of Western liberal democratic states, for example, white, i.e. Anglo Saxon or Caucasians on the ground of their race, or men on the ground of their gender) ought to not to be able to claim the protection of hate speech regulation. And we should also consider the purpose of the speech. If the purpose of the speech is to criticize discrimination, and raise public awareness, or if it is used in critical journalism practices, academic research, it may not be considered hate speech. Systemic marginalisation is taken to mean pervasive, institutionalized exclusion presenting in patterns and practices that are perpetuated in, and through, ostensibly neutral institutional principles, e.g. racism, sexism, ageism and discrimination against the disabled. (Sinpeng, P11)

We should also clarify the sources of speech ‘authority’. Whether it is delivered from formal institutions such as managers, or police officers who possess power granted by the system; or amplified through actions such as liking, sharing and commenting by informal authority. Apart from these two, there is also structural authority in which racist or sexist speech is granted environmental support.

The speech needs to be an act of subordination that interpolates structural inequality into the context in which the speech takes place. In doing so it ranks targets as inferior, legitimates discriminatory behaviour against them, and deprives them of powers. (Sinpeng, P11)

Facebook’s current censorship system tends to focus on regulating extreme and violent speech, but some discriminatory expressions are very subtle. For example, some people may say that LGBTQ+ individuals can easily choose and change their gender identity and sexual orientation. Such statements are arrogant and dismissive, as they deny the life experiences and identity recognition of this group, and also attribute to the dangers of conversion therapy and human rights violations. (Sinpeng, P12)

Case study of Meta’s changes in content rules

In January 2025, Meta announced significant changes to its content review policy in order to balance free speech with responsible platform management. These changes included dropping the third-party fact-checking program, introducing community ratings, and adjusting its treatment of political content. Despite Meta’s claims that the changes are intended to promote open discussion, the removal of fact-checking and the relaxation of restrictions on hate speech raise serious concerns. Allowing more offensive and discriminatory speech could lead to a proliferation of hate speech on the platform and even affect the stability of society. (Joel, 2025)

The meta platform states that by December 2024, they will be removing millions of pieces of content every day. While these actions represent less than 1% of the content generated each day, they believe that 1 to 2 out of every 10 of these actions may be wrong (i.e., the content may not actually violate their policies). (Joel, 2025)

Zuckerberg described Meta’s content review system as a return to its mission of “making the world more open and connected“. While “connecting the world” has been a core goal of Meta since 2014, it was initially more about expanding the size of its user base than facilitating the exchange of political views. (Andrew, 2025) Zuckerberg explained these changes in censorship rules in a three-hour interview with longtime right-wing viewer Joe Rogan. That is, freedom of speech should be absolute, and social platforms should have no role at all in determining what can and cannot be shared in their apps.

His current emphasis on “connecting everyone” is somewhat misleading; in fact, Meta’s primary goal has always been commercial growth and market dominance. From this perspective, the latest policy change is more of a strategic shift than a return to philosophy, and contradicts Meta’s commitment to content review over the past decade. (Andrew, 2025)

For example, in 2015 Zuckerberg praised Facebook’s role in supporting the LGBTQ+ community, while today’s ease of hate speech rules seems contradictory, and after the Charlottesville shooting in 2017, he promised to make Facebook a platform where “everyone feels safe,” but the new rules could run against that promise. The new rules could renege on that promise. (Andrew, 2025)

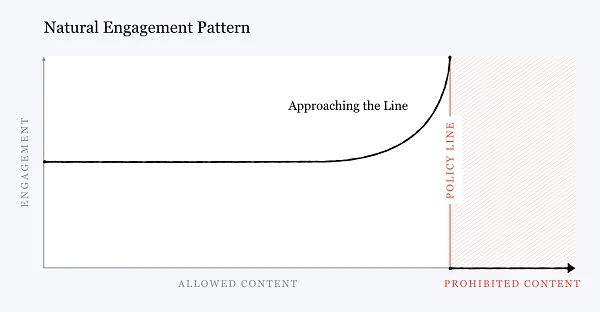

In 2018, the U.S. election controversy prompted Meta to emphasize preventing abuse of the platform and limiting the distribution of content that is close to violating the law but not fully so. Zuckerberg has noted that this type of content tends to receive a higher level of interaction and must therefore be controlled. However, the latest censorship rules appear to contradict past statements and undermine Meta’s previous commitment to content review and contrary to its previous promises and missions. (Andrew, 2025)

Whether community notes, which are successful in some ways and fail in others, are a substitute for third-party fact-checking in terms of responsiveness and performance. The main flaw in community notes remains its reliance on political consensus to display notes (i.e., note contributors with opposing political views need to agree that notes are necessary) to ensure the neutrality of display notes. Independent analysis suggests that such an agreement will never be reached on many of the most divisive issues, and therefore most of the notes on these key issues will never be shown. This could mean that political misinformation, which could gain more momentum under a Trump administration, spreads farther in Meta’s app than it does on X. (Andrew, 2025)

Since 2021, Meta has reduced the amount of civic content (e.g., posts about elections, politics, or social issues) based on user feedback, but that approach was fairly straightforward. Now, Meta plans to apply a more personalized strategy to bring back political content on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. This means that civic content from people and pages you follow will be sorted based on explicit signals (such as “likes”) and implicit signals (such as viewing post) just like any other post. The platform will also recommend more political content and give users more control over how much of that content will appear on their news pages. On the one hand, this approach better matches the user’s personal preferences and on the other hand, improves engagement by providing content that the user has clearly expressed interest in. (Joel, 2025)

Meta‘s change in content rules shows how decisions taken in the name of promoting freedom of speech can reinforce inequality expression and lead to worse forced silences—especially when made by platforms with global reach but limited external accountability.

Solution on moderation of hate speech

In view of these problems, it is clear that content management cannot be accomplished by technical managers alone. So, what would a more balanced, responsible approach look like?

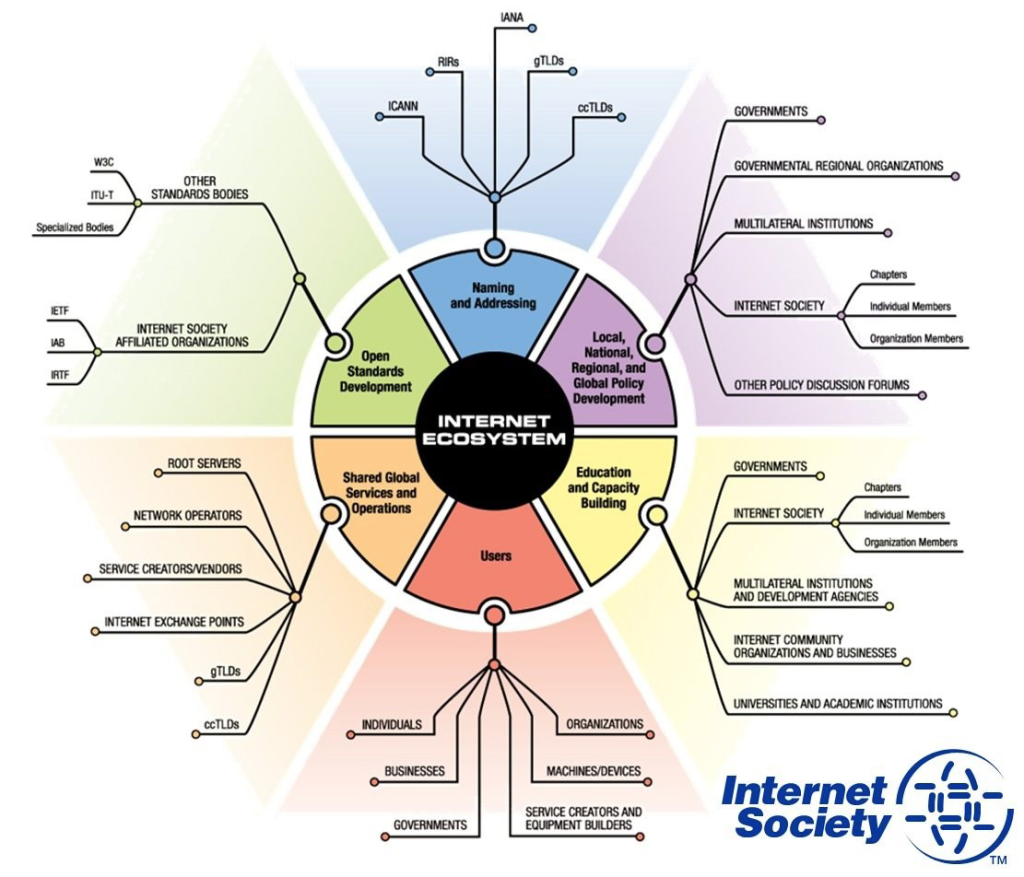

A multi-stakeholder approach is needed to address online hate speech and victimization. The multi-stakeholder approach is a toolbox, not a single solution. Many people talk about ‘the multi-stakeholder model’ as if it is a single solution. But in reality there is no single model that works everywhere or for every issue. Instead, the multi-stakeholder approach is a set of tools or practices that all share one basis: Individuals and organizations from different realms participating alongside each other to share ideas or develop consensus policy.

Platforms should invest in better review tools, improve artificial intelligence algorithms and train human reviewers to recognise cultural and contextual nuances. In addition, transparency in content review policies can help build trust between users and platforms.

Community engagement is another key factor. Platforms can empower users by providing clear complaint mechanisms and allowing community participation in review decisions. Some platforms have experimented with community-based auditing, but some users have reported that the response time is not very timely and the results of the audits are not satisfactory.

Governments and policymakers can also play an important role in regulating cyberspace. Regulation can help curb hate speech, but it must be aimed at protecting freedom of expression, not stifling diverse opinions. Digital platforms must achieve the right balance if they are to remain secure and at the same time open to all users.

Online hate speech and harm will not disappear overnight, but there are ways to improve the situation:

The definition and impact of hate speech differ from region to region, depending on different cultures, languages, social contexts and political statements. So It is important to work closely with protected groups to more accurately define hate speech in specific contexts and cultures, and provide multi-language training modules to help content review teams better identify and respond to such expressions.

In addition, it is crucial to improve review accuracy by optimizing dialect detection algorithms. Platforms should invest in AI tools capable of detecting hate speech with greater accuracy. These tools must be designed to understand context, cultural nuances, and linguistic variations to differentiate between harmful content and legitimate discourses. For example, dialects such as ‘Bisaya, Maguindanao and Marano’ in the Philippines have low recognition rates in mainstream language censorship models and need to be optimized. (Sinpeng,p27)

In the meantime, transparency is the key to boosting public trust and improving the fairness of content review. building regional trust agencies, such as Digital Rights Watch founded in Australia, can encourage the government, platforms, and CSOs to engage in hate speech governance together, rather than letting a single section unilaterally decide on censorship models and rules. This is similar to the European Union’s model of multi-stakeholder approach, which helps to develop a fairer and more effective hate speech governance strategy.

Platforms should actively involve users in content regulation while ensuring that community-based initiatives are fair and effective. Users must have straightforward ways to report hate speech, with prompt responses from moderation teams. Platforms should implement systems that provide feedback on report outcomes, demonstrating accountability in content review processes. However, issues such as delayed response times and inconsistent enforcement must be addressed to ensure effectiveness and fairness.

Laws aimed at curbing hate speech should be designed to hold platforms accountable while ensuring they do not stifle legitimate discussions. Governments must strike a balance between fostering an inclusive digital environment and protecting freedom of expression. The establishment of regional monitoring programs can strengthen the regulation of hate speech. Based on the experience of the European Union, we can promote multi-stakeholder approach among governments, platforms, and organizations to ensure fairness and consistency in preventing hate speech.

Through these efforts, we can endeavour to make online platforms that both promote freedom of speech and effectively contain the dissemination of harmful content.

Conclusion

The early advocates of free expression strongly argued that the Internet is a platform for freedom of speech. In his ‘Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’, John Perry Barlow (1996a) asserted that through the internet ‘we are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity‘. However, the large-scale circulation of hate speech and other forms of online abuse shows that this kind of free speech absolutism needs to be considerably modified in the current legal, regulatory, and business environment.

The critical question now is whether platform companies themselves can be relied on to moderate their content in the public interest or whether the problem points in the direction of government involvement. (Flew, 2021)

Meta’s adjustments in hate speech management actually reflect the tech platform’s longstanding struggle between commercial growth and social responsibility. The core business model of social media relies on user activity and interaction data, and content that is aggressive, emotional or even polarizing tends to bring higher user engagement. And easing content censorship may allow platforms to attract more traffic, increase advertising revenue and drive commercial growth.

While from the perspective of platform responsibility, reducing interference in hate speech could have serious consequences. Social media has become an important forum for public opinion on political and social issues, and once harmful content is not effectively controlled, it may exacerbate social division and even trigger violence in reality. In addition, it is doubtful whether Meta’s move can truly “promote open discussion”; while less censorship may allow for the expression of more diverse viewpoints, if the platform lacks an effective balancing mechanism, the voices of powerful groups may suppress the voices of vulnerable groups, leading to a deterioration in the environment for discussion, and some users may even be afraid to express their views due to fear of attack, which will consequently lead to a decline in the diversity of discussion and freedom of expression.

In summary, Meta’s adjustment may bring short-term commercial gains, but there are mistakes in terms of social impact and long-term development. If the platform fails to find a reasonable balance between free expression and content censorship, it may finally be counter-productive, failing to facilitate healthy public discussion and facing greater external regulatory pressure.

References

Andrew Hutchinson (2025, January 12) Everything You Need To Know About Meta’s Change in Content Rules. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/everything-to-know-about-meta-political-content-update/737123/

Flew, Terry (2021) Hate Speech and Online Abuse. In Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, p. 91

Flew, Terry (2021) Hate Speech and Online Abuse. In Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, p. 94

Global Partners Digital & Digital Rights Watch. (2021, November). Joint submission to the Online Safety (Basic Online Safety Expectations) Determination 2021 [Submission document]. Digital Rights Watch. https://digitalrightswatch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Global-Partners-Digital-Digital-Rights-Watch-Joint-Submission.pdf

Internet Society (2016) Internet Governance: why the multi-stakeholder approach works.https://www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2016/internet-governance-why-the-multistakeholder-approach-works/

Joel Kaplan (2025, January 7) More Speech and Fewer Mistakes. https://about.fb.com/news/2025/01/meta-more-speech-fewer-mistakes/

Parekh, Bhikhu. (2012) “Is There a Case for Banning Hate Speech?” In The Content and Context of Hate Speech: Rethinking Regulation and Responses, edited by Michael Herz and Peter Molnar, P40. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final Report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. Dept of Media and Communication, University of Sydney and School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdfLinks to an external site.

Be the first to comment