One of my friends and I often exclaimed “Big data is Horrible!” when we were speaking online. A common situation in social software is that when we talk about a topic, we can see the topic in another platform’s content push. And its impact on our daily lives is not just to make us see more familiar things. Our cognition will also be changed by big data and unknowingly introduced to the path of prejudice and hatred in controversial issues such as gender.

The topic of Horrible big data implies a potential problem that we don’t normally notice – the control of massive digital monopolies over vast amounts of personal data and the wider socio-cultural implications of the opaqueness of the algorithms within (Flew, T. 2021). We attribute this phenomenon to the technology of “big data” because it is not based on conspiracy theories like Area 51 or Lizard Man, but rather on real technological foundations. Research shows that the ability to capture, analyze, and use unprecedented amounts of personal data for various purposes is transforming contemporary economies and societies (Kitchin, 2014; Meyer-Schonberger & Cukier, 2013 as cited in Flew, T. 2021). Thus, the information gathering of users by social media platforms is self-evident.

Is It Really Not Alarmist?

Perhaps some people will question: “I can simply go online and chat with my friends for a few days. Can this reveal anything private about me?” They may think they’re not giving away anything online, but studies have found that users’ habits reveal their preferences. User characteristics can be inferred from restricted data, for example, personal characteristics can be inferred from data that is considered less sensitive. (Park, S., Matic, A., Garg, K., & Oliver, N. 2017) In other words, when a user visits a certain key topic or other topics related to the topic multiple times, the algorithms of the relevant platform will think that the user is interested in this kind of information, to push this kind of information more frequently to achieve the purpose of so-called personalised service, and the phenomenon that the topics people just talked about will immediately appear on the recommendation page. As a result, people’s information behaviour has the characteristics of “fragmentation” and selective exposure (Zhang, X., & Zhang, J. 2022), and the topics that people avoid will gradually fade out of their vision. However, when people are like herded sheep, unsuspecting to follow the recommendation of big data, they do not realise that the so-called personalized push is a black box, and they do not know what terrible things can be born from it.

What’s Horrible About It?

Existing research describes the term black box as a system that operates in a mysterious way, where we can observe its inputs and outputs but not know what is going on. (Pasquale, F. 2015) In other words, the internal data flow of big data algorithms is automatic, and the decisions they make to influence and guide users cannot be directly supervised. And deconstructing the black boxes of big data is not easy, because they are determined by complex formulas devised by engineers and guarded by lawyers. (Pasquale, F. 2015) On top of that, the algorithm is only learned by historical data, and history itself is full of biases. (Noble, S. U. 2018) The formulation of big data itself does not understand the meaning of language, nor the morality of human society. and unfortunately, the public is minimally aware of these shifts in the cultural power and import of algorithms. (Noble, S. U. 2018) They may even feel that this so-called personalized push phenomenon brings some kind of convenience. In the face of the recommendation of the algorithm, people can more easily find their opinion supporters, so they do not care about their information being collected. Even if users care, they lack rights because the legal reality is that social media platforms belong to the companies that created them, and they have almost absolute power over how they are run. (Suzor, N. P. 2019)

As a result, user abduction by big data can happen out of control – big data forces us as users to constantly see what we are comfortable with, tending to form valuable identities and may even resist other different but meaningful information. (Chen and Wang, 2019 as cited in Zhang, X., & Zhang, J. 2022) Therefore, based on people’s opinions being strengthened by big data, people’s prejudice and hatred will also be unconsciously strengthened by the recommendations brought by big data.

Algorithms and Hate Narratives

When it comes to hate speech and attacks, though, all platforms have rules in their technical design that limit the types of content that can be posted and visible (Suzor, N. P. 2019). However, these rules obviously cannot fully prevent the fermentation of public opinion. The social atmosphere formed by biased speech is still rapidly forming under the information cocoon room formed by the automated push algorithm and even breaks the restrictions of the platform to form a subcultural narrative. My friend and I also talk about controversial topics online and discuss them on different sides. Such as gender, social class and ethnicity. Generally speaking, I respect culture and feelings, take the side of the disadvantaged, and challenge the necessity of current norms, while my friend is more inclined to emphasize technology and rationality, defend the status quo, and support traditional values. This may include some biased speech, including attacks on certain groups.

My friend, for instance, was quick to embrace the emerging “new male chauvinists”. Such public opinion first appeared to be dominated by masculinity. In communities keen to discuss technology, the study notes that while the geek culture of male groups promotes deep interaction with niche interests, it also shows a potential bias towards gender and racial issues. (Massanari, A.2017) This opinion argues that men are the vulnerable group in modern society who are oppressed by women. One study noted that in many Reddit discussions, women are portrayed as manipulating men using ‘patriarchal society’ theories for financial and legal gain (Massanari, A. 2017). As the theoretical foundation of the new male power movement, the new male power aims to win the necessary power for men from the oppression of women through the struggle of public opinion. The two real-world cases that my friends and I have discussed are the embodiment of this phenomenon in the Chinese Internet and also show the process of the algorithm for user information characteristics leading the public opinion to the extreme and division.

The Fat Cat Incident and Judge Wang Jiajia Incident: True Stories and Conflicts

First came the tragedy known as the “Fat Cat incident”.

A man named “Fat Cat” and a woman surnamed Tan reportedly met online and developed a romantic relationship offline, as well as financial exchanges. Then both sides experienced emotional ups and downs. Tan tries to separate from the fat cat and calm down for a while, while the fat cat tries to use the money to save the relationship, and after failure, chooses to jump into the river to commit suicide. Since then, public opinion began to denounce Tan as a woman to accepted money but did not obey the wishes of the fat cat behaviour, and spontaneously through the takeaways to the fat cat suicide site for worship. (Chongqing Nanan District Public Security Bureau, 2024)

My friend, like most netizens, believes that Tan tried to extract material benefits from her boyfriend’s fat cat, and induced his suicide by refusing to have a relationship, in line with the narrative of women oppressing contemporary men. On the contrary, the messages I accept and my friends around me believe that money is not enough to be a necessary condition for a woman to agree to a romantic relationship and that women have the right to refuse an emotional relationship.

In the case of Judge Wang Jiajia, a man named Dang Zhijun was injured in a car accident and sued the offender for more than 18,000 yuan in compensation. The trial judge, Ms Wang Jiajia, combined with the opinions of the traffic police and other departments, ruled that the man only supported his claim for compensation of more than 9,000 yuan when he disclosed that the number of days he was hospitalized did not match the actual situation. Leading to the murder of judge Wang Jiajia (CCTV News, 2024).

In this case, my friend and the online tweets he received supported the man’s murderous behaviour, arguing that what he was doing was a “great struggle” by men oppressed by society and women, like a “Promethean” tragic hero. In contrast, the relatively official and my attitude is that choosing to kill someone for the compensation of 9,000 RMB is contempt for the dignity of the law and administrative procedures and has nothing to do with gender or structural inequality.

From these two incidents, it seems that my friend and I live in completely different worlds. We are divided into two kinds of people by automated algorithms. We receive completely different information, public opinion and Peer Pressure from the network world, which shapes the different world in our eyes, but we find it difficult to understand the world that other sees.

The Secret of Mice and Watermelon Being: Information Cocoon Rooms and Gender Narrative Memes

In broader social norms that go beyond specific events, the algorithm continues to reinforce this tendency by judging a user’s stance based on past behavior. Men who frequently visit certain communities are more likely to hold anti-feminist views and support restrictions on women’s rights in real life. (Massanari, A. 2017) On the Chinese Internet, women’s appeals for their rights are regarded by male groups as asking for bride price or related benefits and slut shaming. Many male netizens also stressed the difficulty of reaching marriage and having children under modern pressure under patriarchal norms and attributed men’s spending obligations under social norms to feminism. However, they ignored or denied the potential that women’s independence could also make them break the shackles of traditional patriarchy and further internalized the objectification of women. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to see that other women are hurt by men in society through the Internet, and they also form a fear of men over time. However, the so-called “men’s rights demands” called for by the new patriarchy mentioned earlier have hardly really been heard and discussed by the female community.

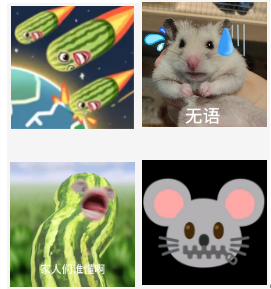

Among them, a relatively visible phenomenon is the meme formed by information cocoon and prejudice, because anti-feminism not only spreads through rational discussion but also strengthens views through meme culture, making them more attractive and spreading (Massanari, A. 2017). This kind of divided gender opposition opinion has also generated specific memes on the Chinese Internet. More representative images are “watermelon being” and “mice”, as shown in the figure:

Some feminists used “watermelon being” as an anonymous image on the Chinese Internet, and then watermelon bars were used to satirize women who actively spoke out, and rats were used by male users to make fun of themselves to express that they were oppressed to the bottom of society by the collusion of women and capital. In the top left corner of the picture, a “watermelon being” hits the earth like an asteroid, symbolizing feminism’s impact on the world order, while in the bottom right corner, a mice’s mouth is locked by a zipper, symbolizing a man’s expression space is locked. These hateful narratives ferment continuously in the closed space constructed by the information cocoon room, forming various subcultural symbols. And such explicit memes also become powerful evidence of the prejudice and hatred brought by the information cocoon. In this case, the concept of Internet users is unconsciously affected by hate speech. People unconsciously accept the worldview shaped by the algorithm and attack those who disagree with them but unfortunately lose the ability to see the problem from another perspective.

Conclusion

Overall, this paper reveals the progression from data misuse to hate speech. That is how “big data” shapes information cocoons and reinforces group bias and hate speech through personalized recommendations. The case study is the embodiment of this phenomenon in gender issues, and how different positions are solidified and polarized by algorithm push. My friends and I, who seem not to be in the same world as me, are like the protagonists in dystopian novels like 1984 or From the New World, who find the world abnormal. They see everything working in the form of anti-common sense and see the contradiction and fragmentation increase, but they have to make themselves part of this grand system. We need mechanisms to break the information cocoon. For example, society should promote cross-group dialogue to reduce algorithmically driven bias. But at least for the more trapped, a quote from last century’s science fiction might still make sense: Knowing where the trap is—that’s the first step in evading it. (Herbert, F. 1965/2021)

Reference

CCTV News. (2024, December 23). Dang Zhijun was sentenced to death! CCTV News. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Cu5MEo50-7HLWt8ty1PBsg

Chongqing Nanan District Public Security Bureau. (2024, May 19). Police report. Chongqing Public Security Bureau.

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 72–96). Polity.

Herbert, F. (1965/2021). Dune (D. Liu, Trans.). Zhejiang Literature & Art Publishing House. (Original work published 1965)

Massanari, A. (2017). Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (1st ed.). NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/9781479833641

Park, S., Matic, A., Garg, K., & Oliver, N. (2017). When Simpler Data Does Not Imply Less Information: A Study of User Profiling Scenarios with Constrained View of Mobile HTTP(S) Traffic. arXiv.Org. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1710.00069

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules? In Lawless (pp. 10–24).

Zhang, X., & Zhang, J. (2022). Formation mechanism of the information cocoon: An information ecology perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1055798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1055798

Be the first to comment