How social media, biased algorithms, and weak moderation systems normalize hate speech against women, minorities, and regional identities in Vietnam—and what we can do about it.

Let’s face it—scrolling through social media in Vietnam can feel like walking through a minefield. One moment, you’re enjoying cat videos or food reviews, and the next, you’re hit with a barrage of hateful comments: insults against women, jokes about ethnic minorities, or toxic bias about people from a different region. Many of us don’t care because we’re so used to it, but make no mistake—these words leave “invisible scars”.

This blog dives into the underbelly of online discourse in Vietnam, examining how hate speech—particularly around gender, ethnicity, and regional identity—has become entrenched in digital culture. It explores how algorithms and poor content moderation let harmful narratives spread and offers some ways we can fix this.

What Counts as Hate Speech?

Hate speech isn’t always about slandering or demonizing others. Often, it’s subtler: stereotypes, jokes that ‘punch down,’ or posing as a debate to stir up controversy in a community. More formally, it is defined as speech that incites discrimination or violence based on characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation (Flew, 2021). But in practice, especially on digital platforms, the lines become blurred. What is offensive to one group may be considered harmless fun by another.

Vietnam: Everyday Hate in Digital Spaces

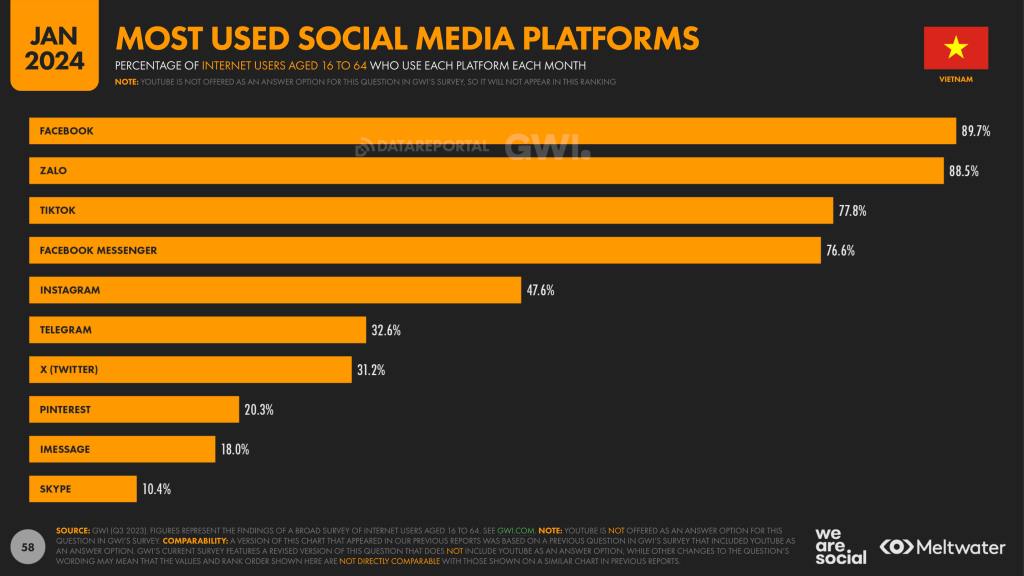

Vietnam is among the countries with the most Facebook users worldwide, with over 70 million users by early 2024 (Kemp, 2024). This online presence is a huge opportunity for social media developers, but it also creates conditions for hate speech. Online hate is not only directed at politicians or celebrities but also at ordinary people. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, you will see it everywhere: in comment sections, viral videos, and forums.

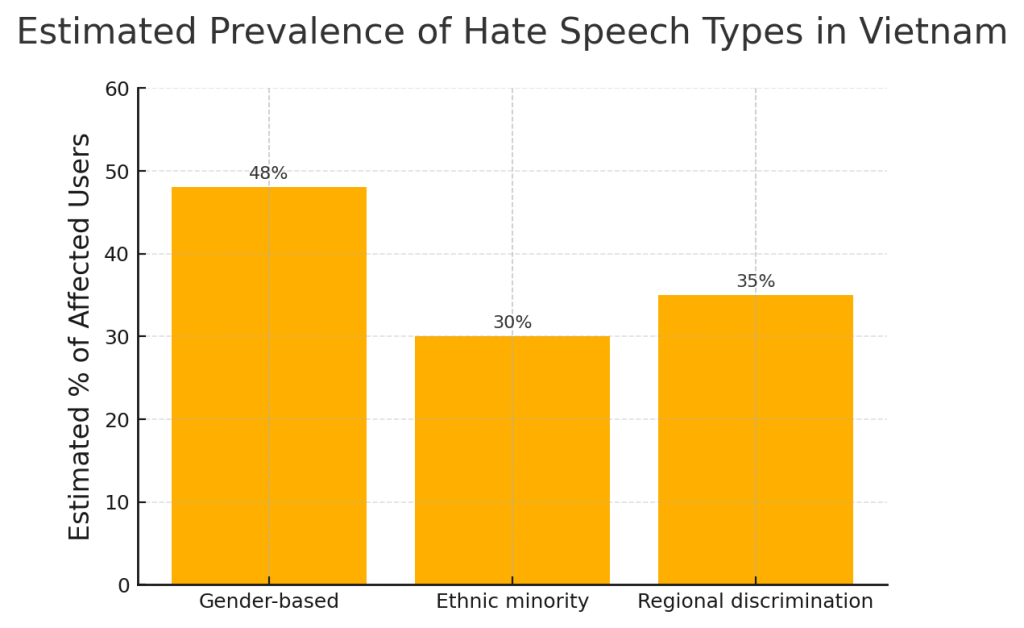

One of the most common forms is gender-based hate. A 2022 survey by the Vietnam Women’s Union revealed that nearly 50% of female users had faced online harassment—including sexual threats, body shaming, and verbal attacks. Influential women, especially those in politics or feminism, face coordinated campaigns to discredit or humiliate them. For instance, when feminist activist Trang Le posted a video calling for stronger gender equality protections in the workplace, she received a flood of toxic replies. Commenters mocked her voice, appearance, and even her personal life—claiming she was “attention-seeking” and “disrespecting tradition.” The video was shared widely, but platform moderation remained silent despite multiple reports.

Ethnic minorities also face online ridicule. Groups like the Khmer, Hmong, and Ede are frequently the subject of demeaning jokes and memes—depicted as ‘backward’ or ‘uncivilized.’ According to a 2023 report by the Vietnam Institute for Human Rights, hate speech against ethnic minorities easily bypasses censors on platforms like Facebook or TikTok.

Regional discrimination is a latent problem online. People from central or northern provinces are often targeted with insults in livestreams or viral posts. Mocking someone’s accent or place of birth may seem like harmless teasing, but if repeated over time, it reinforces real social divisions. A viral Facebook post in 2023 featured a satirical “map” that stereotyped each region with offensive descriptors. Despite public backlash, the post remained up for days and was shared over 100,000 times. VietnamNet (2023) reported an increase in regional hatred in domestic controversies, especially when they involve the origins of famous figures.

Gender-based hate is the most commonly reported (approx. 48%), followed by regional discrimination (35%) and ethnic-based hate (30%).

Sources: Vietnam Women’s Union (2022), Vietnam Institute for Human Rights (2023), VietnamNet (2023).

These are no longer isolated incidents but are increasingly becoming a cultural pattern that is being expressed digitally. It reflects the deterioration of social media etiquette. It is these things that make social media spaces toxic and are breaking people down. Victims often withdraw from the online space altogether, robbing public discourse of diversity, authenticity, and courage.

How Platforms Make It Worse

Let’s be honest: social media platforms are designed to keep us engaged; they don’t keep us safe. Their algorithms don’t care about human emotions and whether something is kind or cruel; they just care about getting a reaction. As for hate speech? That gets a lot of clicks. In Vietnam, this means misogynistic jokes or regional mockery often go viral—not because people support it, but because they react to it.

Studies by Massanari (2017) and Roberts (2019) show that platforms like Reddit, Facebook, and TikTok unintentionally encourage inflammatory content because it tends to be more engaging. Massanari calls this design a “toxic tech culture,” where platforms profit from polarizing content. While community standards are designed to limit hate speech, enforcement is uneven. Vietnamese users report that when hateful comments, especially those targeting women or minorities, are reported, they are often flagged by moderators for temporary recognition and then automatically deleted. The more aggressive the comment, the more likely it will be promoted. In Vietnam, this has contributed to the normalization of hate speech, especially when it is sophisticatedly coded or meme-based.

For example, a series of TikTok trends in 2023 where users mocked rural dialects and minority languages under the guise of “language challenge” videos. These videos were often reposted or duetted for clickbait and were effective, attracting millions of views. Despite harsh criticism from the community, TikTok’s moderation team failed to keep up as these offensive content were disguised in various forms such as music videos, challenges, and entertainment content. In many cases, the trending sound itself was offensive, but it remained accessible in the app’s library for weeks before TikTok’s moderation team discovered the problem or the government intervened.

Faced with mounting pressure, Meta updated its Community Standards in late 2023 to prioritize “context-aware” moderation in Southeast Asia. The company pledged to expand its Vietnamese-language moderation teams and redesign its AI models to better recognize local nuances. By 2025, Mark Zuckerberg announced improvements to its Community Standards with a better, less error-prone appeals system. This will allow users to express their opinions freely across Meta’s platforms and have the right to appeal posts that are not removed without cause. At the same time, the system is developing a more sophisticated way to detect coded hate speech. TikTok has also created content safety teams and updated its rules on behavior that violates its community standards. But experts say policies alone won’t solve the problem. Left unchecked, algorithms will continue to amplify bad things because they simply attract more attention.

The Role of Users and Communities: Beyond Reporting

While platforms and policies shape the digital landscape, we—everyday users—are the ones living it. That means we have more power than we think.

First, users can actively disrupt hate speech by refusing to amplify it. That doesn’t always mean joining in the fray in the comments section. Sometimes it means not sharing that meme, not laughing at that sexist joke, and not promoting content that harms others, even if it’s just “for fun.”

Education also plays a role. Not all hate speech is intentional—especially when it comes to regional stereotypes or common misogyny that have been normalized for decades. Digital awareness campaigns, especially those implemented in schools and youth spaces, can teach the next generation how to spot toxic patterns, understand online accountability, and become constructive digital citizens.

Finally, solidarity is important. Speaking up when someone else is being targeted—especially if you are not the one being harmed—sends a powerful message. It tells platforms, communities, and the aggressors themselves: this is not okay, and we will not turn a blind eye.

Hate speech online is not inevitable. But it is certainly reinforced when people normalize and accept it. There is no accountability for those invisible scars, and they will never heal unless we act.

Balancing Free Speech and Safer Platforms: What Can We Actually Do?

Whenever we talk about regulating hate speech online, the same concern arises: “But what about freedom of speech?” And that is a fair question. No one wants the internet to be over-censored or algorithms to become illegitimate. However, as Suzor (2019) has said, freedom of speech does not mean freedom to harm. Your right to speak ends where others’ right to safety begins.

Hate speech on online platforms often hides behind the slogans of neutrality. But algorithms are not sophisticated enough to analyze that. Left unchecked, hate speech not only persists, but becomes embedded in the fabric of the digital space. It marginalizes the voices of vulnerable groups and distorts public debate. Under the guise of “free speech,” some users use words to harass, degrade, or threaten, and platforms allow them to do so.

This is where Helen Nissenbaum’s (2018) concept of “contextual integrity” becomes so important. Harm is not always about the words themselves, but about the context in which they are said, and the intention behind them. A comment may seem like a joke to one group of people, but to another it may reinforce centuries-old prejudices. Global platforms like Facebook and TikTok cannot ignore these cultural nuances, especially in diverse, multilingual environments like Vietnam.

So What Can We Actually Do?

Fixing online hate isn’t about censoring everything, it’s about building smarter, fairer systems. First, platforms need to do a better job of moderating content. This can be improved by hiring local teams, understanding cultural nuances, and applying rules consistently. That gives users a real right to complain when they are targeted. Second, we need transparency. How do algorithms decide what we see? How are appeals handled? Without answers, accountability is impossible. Lastly, governments need to play a more active role—not by censoring dissent, but by building smart, rights-based regulation. Laws like the EU’s Digital Services Act or Australia’s Online Safety Act offer promising frameworks. These laws don’t ban speech—they hold platforms accountable for risk. They create systems of oversight and transparency, without turning governments into arbiters of truth. Because fixing online hate isn’t about silencing everyone. It’s about creating a space where everyone can speak safely.

Conclusion

We often think of hate speech as something that screams, curses, and chaos. But in modern society, it often happens in a very quiet way. Hate speech now creeps into our daily lives like a seemingly innocent meme or a scathing comment, then disappears into a scroll. But those cuts leave invisible scars on those they target.

In Vietnam, where social media is an integral part of daily life, the impact of unchecked hate speech is growing. It not only damages mental health but also reshapes public discourse. It humiliates women, minorities, and regional voices, eroding democratic participation and trust in the digital community.

Let’s stop pretending that platforms alone can solve this problem. Yes, Meta and TikTok need better policies—and they’re starting to change. However, cultural context, algorithmic transparency, and local enforcement are more than just marketing gimmicks to bolster user trust. Governments must also act, not by blindly policing speech, but by creating smart, rights-based regulation.

And perhaps most importantly, we—the users—must change how we interact. Because algorithms are built on user data. Platform tools use machine learning and AI to analyze them. So it’s not a good idea to choose silence. Speak up when you’re uncomfortable. Refuse to normalize abuse as “just a joke.” Support those who are targeted. Choose empathy over entertainment. Because the price of silence isn’t just personal—it’s collective.

Silence breeds hate. It’s time to start speaking up and act now.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated culture. In *Automated Media* (pp. 44–72). Routledge.

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2018). *Social media mob: Being Indigenous online*. Macquarie University. https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/social-media-mob-being-indigenous-online

DataReportal. (2024). *Digital 2024: Vietnam*. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-vietnam

DevThePineapple. (n.d.). *Hate speech is not free speech* [Digital poster]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CX5yD9LNZ5U/

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In *Regulating platforms* (pp. 91–96). Polity Press.

Getty Images. (n.d.). *Mark Zuckerberg free speech background image* [Editorial use image]. https://nowbam.com/metas-new-years-resolution-fewer-mistakes-more-speech/

GWI & DataReportal. (2024). *Most used social media platforms in Vietnam (Jan 2024)* [Infographic]. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-vietnam

Le, T. (2022). Personal commentary on workplace equality [Video]. Facebook. (Documented in Digital Rights Vietnam archive, 2023)

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. *New Media & Society*, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Meta. (2023). *Community Standards Enforcement Report*. Meta Transparency Center. https://transparency.fb.com/data/community-standards-enforcement/

Meta. (2025, January). *More speech, fewer mistakes: Improving moderation in 2025*. Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2025/01/meta-more-speech-fewer-mistakes/

Meta. (n.d.). *Hate speech policy*. Meta Transparency Center. https://transparency.meta.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. *Science and Engineering Ethics*, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9975-1

NowBam. (2024, January 5). *Meta’s New Year’s resolution: fewer mistakes, more speech*. https://nowbam.com/metas-new-years-resolution-fewer-mistakes-more-speech/

Roberts, S. T. (2019). *Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media*. Yale University Press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). *Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific*. University of Sydney & University of Queensland. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

Social Media Today. (2024, March 6). *Everything to know about Meta’s political content update*. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/everything-to-know-about-meta-political-content-update/737123/

Suzor, N. (2019). Who makes the rules? In *Lawless: The secret rules that govern our lives* (pp. 10–24). Cambridge University Press.

TikTok. (2023). *TikTok launches Southeast Asia content safety hub*. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Technology/TikTok-opens-SEA-content-safety-hub

Tuổi Trẻ Online. (2023, May 9). *TikTokers bị chỉ trích vì video chế giễu trang phục dân tộc thiểu số*. https://tuoitre.vn

Vietnam Institute for Human Rights. (2023). *Digital discrimination report*. Internal policy brief.

Vietnam Women’s Union. (2022). *Survey on online gender-based harassment*. Internal publication.

VietnamNet. (2023, August 12). *Hate speech still rampant on social media*. https://vietnamnet.vn

Be the first to comment