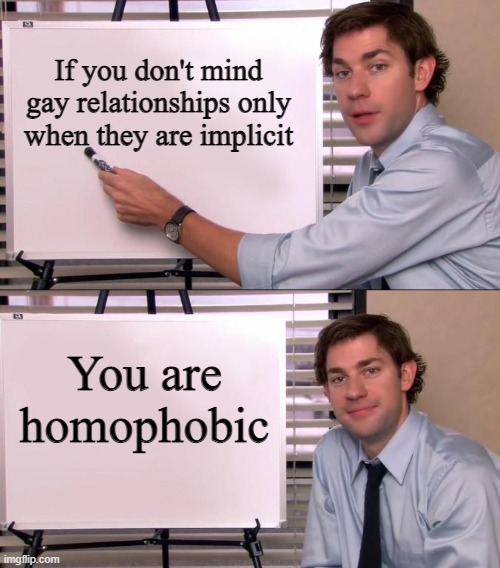

Image from Reddit, retrieved April 2025

Introduction

Have you ever scrolled past a comment like this on social media:“ I have nothing against gay people—as long as they are not too in-your-face”, or “ My best friend is trans, so I definitely do not discriminate against them”. These words sound polite, even open-minded, but are they really harmless?

On the surface, such statements avoid using insulting terms, they sound tolerant, reasonable, even supportive. But look closer, we will find that they quietly draw a line between who is normal and who must stay careful to be accepted. On platforms like TikTok, Reddit and YouTube, jokes and imitations targeting LGBT individuals circulate freely under the excuse of being “just for fun”. These videos are not marked as hate speech and often unconsciously shared by viewers as entertainment content.

Soft hate does not shout and insult directly, but it blends into humor, into reasonableness and everyday speech. That’s what makes it so effective and easy to miss. In this piece, we will break down how such words hurt, how platforms and cultural norms give it room to grow, and what role we unintentionally or not, might be playing in letting it spread.

Some Words Don’t Curse But Still Hurt

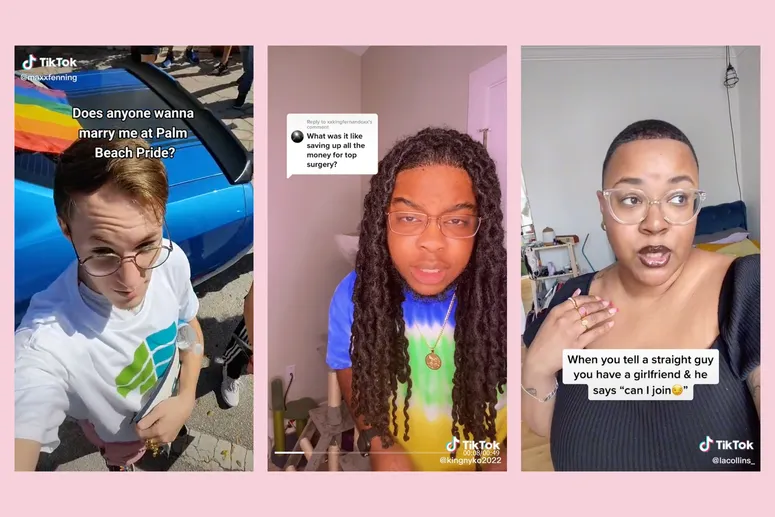

Screenshot from TikTok interface, retrieved April 2025

The harm caused by hate speech does not happen all at once, but seeps in slowly, folding itself into everyday life. As Tirrell (2017) puts it, some words act like “chronic toxins”, not explosive, but continually accumulating negative effects. They changing the capacity of people to participate fully and equally in society (Tirrell, 2017). Compared to blunt attack like “Go back to your country”, statements such as “I support gay people, but let’s not be too loud about it” sound more polite, but often carry a deeper sense of oppression.

These words sound calm and non-hostile, which makes them easier to say, laugh at and spread to more people as ordinary content. But for marginalised groups, these seemingly harmless words still deliver a clear message: if you want to be accepted, you had better keep yourself out of sight first (Tirrell, 2017).

So why are these kinds of comments so common today? It is not just about individual bias, but more important, the real issue lies in how they are woven into platform recommendation algorithms and our daily habits of using social media. Matamoros-Fernández (2017) calls this phenomenon “platformed racism”, noting that when hate speech is wrapped in jokes or satire, it becomes harder to identify as harmful and more likely to be promoted by algorithms. The platforms themselves may not be directly endorsing such content, but their algorithms do favor things that are more likely to spark comments, debates, or shares (Gillespie, 2010; Van Dijck, 2013).

Many users also shield themselves from criticism with phrases like “I was just saying” or “You are being too sensitive”. Once biased remarks are wrapped in the shell of humor, they suddenly seem to be less serious. And over time, instead of being questioned, they are more likely to be accepted and repeated (Daniels, 2009).

So we have to ask ourselves: when these biased jokes keep showing up, are we really joking or have we become accustomed to the bias behind it?

When Prejudice Wears Humour: The Case of TikTok’s Transgender Mockery

On TikTok, transgender creator Dylan Mulvaney drew wide attention for her video series “Days of Girlhood”. She documented her gender journey in a light-hearted and honest way in the hope of gaining more understanding and acceptance. But for some users, her content became material for parody and mockery. They posted videos mimicking her with exaggerated make-up, stereotypical tone of voice and performative gestures, insisting it was all meant to be “funny” or “just self-expression”.

These mimicries may not involve explicit slurs, but they work through entertainment to normalize prejudice against transgender people. As Matamoros-Fernández (2017) notes in her study on platformed racism, easy forms of expression such as short videos make prejudice easier to circulate and harder for platforms to treat it as a problem. Gillespie (2010) further points out that platforms’ algorithms tend to favor whatever draws higher engagement. That means funny-looking hate speech more likely to appear in recommendations than outright attacks, just because it looks entertaining.

In response to this mockery, Mulvaney has responded publicly. She emphasized that this kind of “performative humiliation” is not only emotionally damaging to the transgender people, but also makes hostility toward them feel more socially acceptable. She also criticised these creators of such content and called on platforms to stop using freedom of expression as an excuse for inaction and to take seriously content that does real harm to marginalised groups (James, 2022).

When prejudice shows up on your homepage recommendations, dressed as something harmless, it is harder to recognize and easier to replicate than abuse. As we scroll through and laugh, do we really realise who is actually being mocked?

How Platforms See but Still Do Nothing

Platforms often claim to be cracking down on hate speech, but when it comes to expressions framed as “just a joke”, their response is usually slow or even missing altogether. And it is not because they cannot act, it is that their systems are designed to prioritize what drives clicks and shares, rather than whether the content is hurting people (Gillespie, 2010).

Gorwa, Binns, and Katzenbach (2020) point out that algorithms today do not understand context or sarcasm, but only respond to keywords and the emotional spikes that drive engagement. Combined with platforms’ heavy reliance on automated moderation, many offensive modelling or banter videos are let off easy because they don’t have swear words. Jane (2017) has similarly noted that many attacks are hidden humor, particularly when aimed at women or marginalized groups.

Meanwhile, platforms frequently blur the lines in their content moderation rules, offering little clarity on the boundaries between “cultural attack” and “humorous expression”. This reflects not a technical failure, but a systemic prioritization of engagement over harm reduction, where content that entertains is left unchecked as long as it doesn’t threaten the platform’s own image.

Why Platforms Choose Not to Act: Strategic Silence and Selective Governance

Image:” Diffusion of responsibility, bystander effect illustration. Crowd is witness of act of crime and is doing nothing.” by Virtualmage. Image ID: 47422863. © Dreamstime.com. Retrieved April 2025. Used under editorial license.

What’s revealing is that platforms clearly can act when they want to. During major political crises or public backlash, they swiftly remove content, suspend accounts, and issue policy statements. When the content is wrapped in humor, they often choose to look the other way. But when the content comes wrapped in “cultural satire”, they often choose to look the other way.

For example, in the case of the Super Straight meme incident, strongly transphobic videos were widely distributed on TikTok, and were only partially taken down after an external backlash. Even now, the platform has yet to clearly explain what rules were applied.

What is even more confusing, even if users report this kind of content, it is often impossible to know whether the platform has reviewed it, and what standards were used. This management is invisible, and it helps creators exploit the system. Victims? They are left waiting with no answer.

Uneven Standards?

It is worth noting that platforms’ response standards are not consistent across different countries and events. While platforms are quick to remove sensitive content during geopolitical events, like the 2021 Capitol riot or the Israel-Hamas conflict, they often hesitate or fail to respond when hate is expressed in cultural or comedic forms, especially those targeting LGBT communities or minorities. As Gorwa, Binns, and Katzenbach (2020) point out, these “asymmetric sensitivities” in content governance is not a result of technical limitation, but rather to the deliberate decision about where platforms choose to draw the boundaries of intervention.

What makes this even more confusing is that even though the platforms do publish community guidelines, there is still a lack of transparency about many key details. For instance, users are often left guessing where humor ends and harm begins, especially when no clear criteria are made public. This lack of visible standards leaves users constantly guessing where the red lines are and leaves victims increasingly voiceless in the face of a complaint system that goes nowhere (Suzor, 2019).

When governance inconsistencies are coupled with opaque mechanisms, soft forms of hate content are more likely to survive in the grey zone. And for the public, this kind of quiet tolerance can send a misleading signal, maybe these expressions may not be that serious after all.

Are We Really Not Involved?

Many short videos that seem to be “just a joke” have gone viral not only because platforms do not block them, but also because we ourselves are reposting them and laughing at them. In many comment sections, videos mocking LGBT communities, people of color, or women are not flagged. Instead, they’re met with replies like “So true haha” or “Don’t be so sensitive”. These interactions give the illusion that such content is widely accepted, which in turn drives the algorithms to recommend it to more people.

Over time, we begin to treat these remarks as just part of the Internet, and stop noticing what is wrong with them. The most terrible thing is that when someone says they feel uncomfortable, they are often accused of being too sensitive or of not having a sense of humor. Thus, the person who made the joke avoids responsibility, while the person who speaks up is seen as the problem.

From the recommendation logic of platforms to the videos we casually scroll past every day, many hate speech continue to spread through subtle tone and seemingly harmless interaction. When we comment “haha so true”, we may unknowingly help push that content further. As Matamoros-Fernández (2017) has argued, once user behavior becomes embedded in the structure of platformed racism, they are no longer just personal choices, but become part of a broader system of cultural production, one that platforms actively encourage.

Some people may never say these words, but they do not question them either. Maybe they think it is not their own business or that no one cares anyway. But it is this silence that makes it even harder for platforms to recognize the problem. What is more difficult to spot is that we shift the blame. Sometimes, we feel like others have made us lose our right to free expression. But that feeling is also a form of bias, we stop asking whether the words are harmful, but start accusing others of overreacting. As Jane (2017) puts it, this is exactly what makes humor so dangerous, it turns aggression into entertainment.

Not “Just a Joke”, Real Harm Is Being Done

In an online world where everything can be turned into a joke and all attacks get shrugged off with “Do not take it seriously”, hate no longer comes with angry voices. It wears the mask of humor that pushes people further into isolation.

From TikTok videos mocking trans people to comment sections echoing with laughing emojis, what we are witnessing is not just prejudice. Algorithms are boosting, moderation is missing, but ultimately what makes these contents spread is us, whether we laugh, whether we share, or whether we say nothing at all.

Stopping hate speech is not just about clicking the report button or waiting for platforms to act. It is a matter of judgment, and a quiet kind of responsibility. So the next time you hear “Just a joke”, it is worth asking yourself, are we really okay?

References:

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

James Factora. (2022). TikToker Dylan Mulvaney Gave a Master Class on Dealing With Transphobic Trolls. Them Magazine. https://www.them.us/story/dylan-mulvaney-transphobic-troll-tik-tok

Jane, E. A. (2016). Misogyny Online: A Short (and Brutish) History (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473916029

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Tirrell, L. (2017). Toxic Speech: Toward an Epidemiology of Discursive Harm. Philosophical Topics, 45(2), 139–162. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26529441

Be the first to comment