FemTech is a thriving multi-billion-dollar global industry. It’s a market of technology products, digital services and/or platforms relating to women’s health issues, including a range of apps for tracking menstrual cycles and fertility that are used by millions.

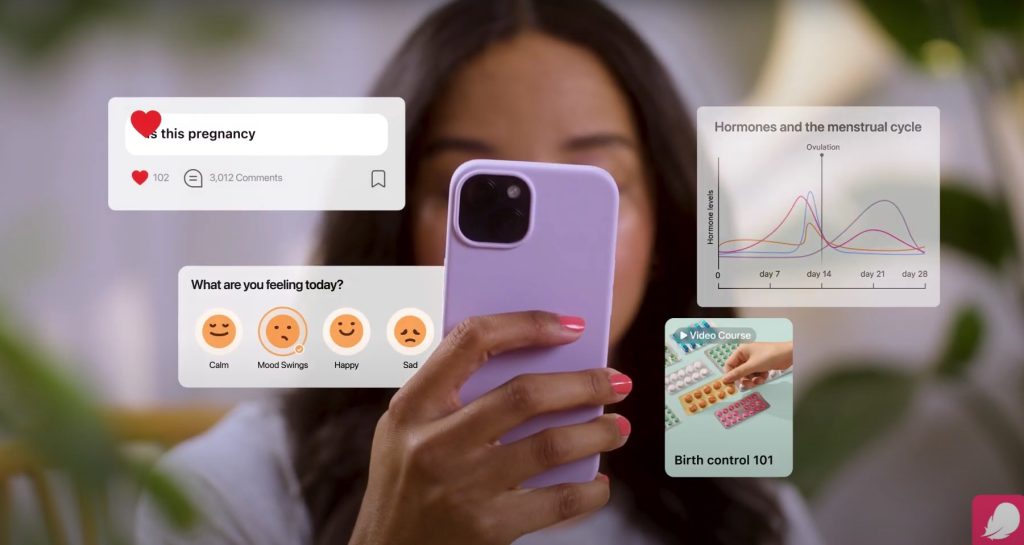

With apps like Flo, Glow, Clue and Ovia, users can log details ranging from their period dates, ovulation and mood, to sexual activity, the course of a pregnancy and even cervical mucus consistency. Proponents tout FemTech tools as a way to address gender bias in women’s medical research and care. Some argue that it’s empowering to be able to manage health data from your personal device. And, in a context where inputting personal data into an app is so commonplace – our whole lives are ‘datafied’ (Van Djick, 2014 in Flew, 2021) – it might seem to be no big deal handing over info about your monthly flow via a little square on your screen.

But are FemTech’s fantasies of female empowerment just that?

Apps and APPs

Recent research from academics at Queensland University of Technology (Hammond & Burdon, 2024) examined the privacy policies of twenty such menstrual cycle tracking apps available in Australia. They found that many apps not only don’t comply with APPs, Australian Privacy Principles, but there is considerable variation and vagueness in their policies and a broad lack of acknowledgement of just how personal, sensitive and intimate this kind of data is.

Questioning the data and privacy practices of FemTech apps bleeds into conversations about broader concepts of ‘digital privacy’ (Goggin et al, 2017) and the power tech platforms have over our most personal data. It prompts concerns about data security and the risk of breaches; about reproductive rights and some scary legal possibilities especially in territories where abortions are prohibited. This reveals blind spots in the way personal health data is governed and protected in our digital society. If left to platform-controlled privacy policies, rather than being subject to more rigorous regulation, it’s clear there could be even more serious harm.

“I Agree”: Your Privacy and Platform Policy

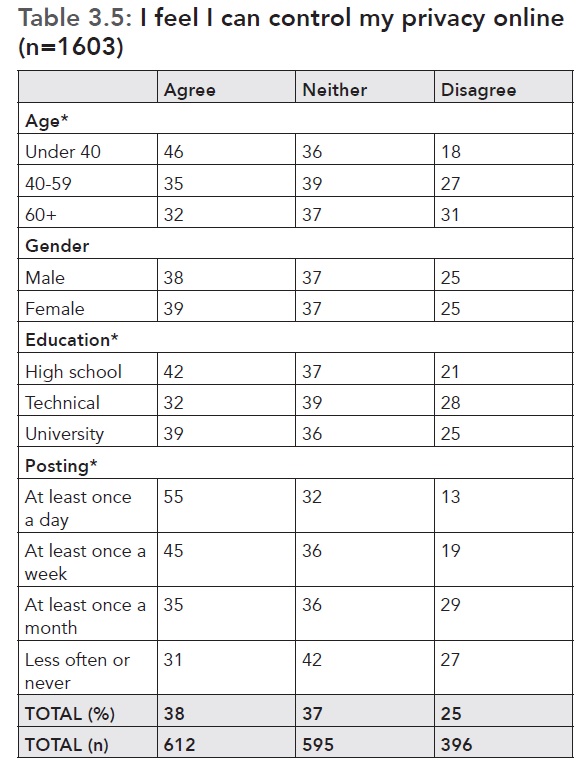

What are our privacy expectations when it comes to the digital platforms we use and our personal data? Scholars such as Terry Flew (2021) note the contemporary reality that much of our personal data ends up under the purview of platforms. Even with national privacy laws, it’s the privacy policies of these platform companies that often seem to define the rules, leading to trade-offs between personal privacy and access (Flew, 2021). Despite widespread acceptance of some level of trade-off, according to the 2017 Digital Rights in Australia Report only 38% of respondents felt that they could control their privacy online (Goggin et al, 2017). This could be partly due to the power asymmetries inherent in terms of service agreements, skewed in favour of platforms, as described by Nicholas Suzor (2019). Privacy policies are similar, in that the platform appears to have the power to define its own terms and they’re often lengthy, vague, legalistic documents that are unlikely to be fully read and understood by users who accept them (Flew, 2021). How many times have we all hit ‘I Agree’ without reading?

In Digital Rights in Australia (p. 16).

What Counts as Sensitive?

The data used by platforms can also be highly personal, as in the case of period and fertility trackers. Helen Nissenbaum (2018) introduces an interesting measure of “contextual integrity” which relates to our ideas or expectations about the ‘appropriateness’ of how our data is treated. She argues for ‘respect for context’, that “consumers have a right to expect that companies will collect, use, and disclose personal data in ways that are consistent with the [social] context in which consumers provide the data” (Nissenbaum, 2018, p. 850). In the case of intimate health data, it seems reasonable to assume an expectation of care around private information consistent with at least some of the norms of the healthcare sector. Unfortunately, research seems to show that the landscape of FemTech apps does not abide by such standards.

Hammond and Burdon’s (2024) research examined the privacy policies of apps including Flo, Clue, Femometer, Ovia and Glow. While they varied, with some offering better protections than others, by and large the research identified a number of ‘deficiencies’ where app privacy policies fell short of the standards of the Australian Privacy Act’s thirteen principles. For example, even though most people would agree that information about menstrual cycles and fertility would be considered ‘sensitive’, none that were available on the Australian Apple App store employed the definition of ‘sensitive information’ that complies with the privacy principle categorisation, which gives health or genetic information a higher level of privacy protection (Hammond & Burdon, 2024, p. 7).

Uninformed Consent and the Illusion of Choice

Hammond and Burdon’s privacy policy analysis builds on earlier research by Katharine Kemp (2023) who also found a troubling number of confusing and misleading claims by popular menstrual and fertility apps. Apps may make consumer-facing claims that they “never sell your personal data to third parties”, and yet, deep in the quagmire of the privacy policy, it may acknowledge that if a platform business is sold, the data it holds becomes an asset of the sale, and therefore can be transferred to the acquiring company (Kemp, 2023).

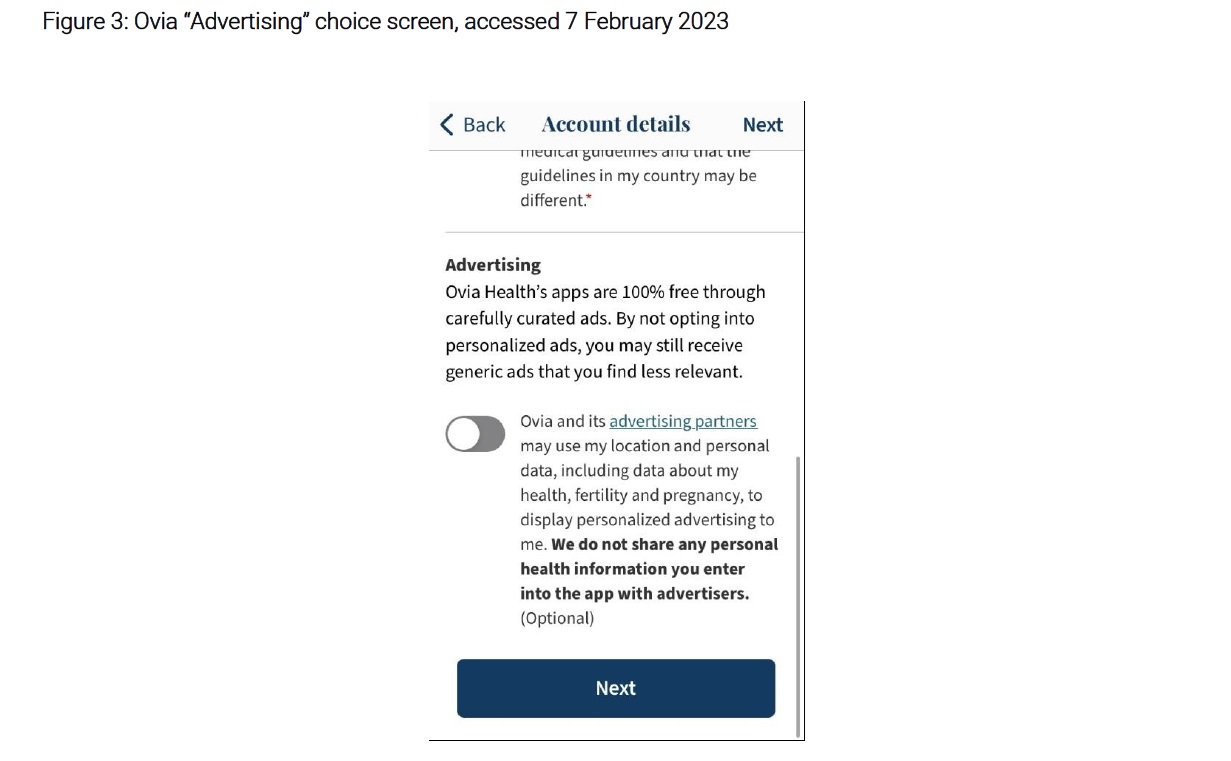

Even in basic interactions with apps it can be difficult to have confidence in individual control over privacy. Kemp uses the example of Ovia which gives users the ‘choice’ of seeing generic or personalised ads. In the one pop-up it claims, “Ovia and its advertising partners may use my location and personal data, including data about my health, fertility and pregnancy, to display personalized advertising to me”, and immediately after, says in bold, “We do not share any health information you enter into the app with advertisers” (Kemp, 2023, p. 15).

As Kemp says, companies control the “choice architecture presented to consumers” (2023, p. 17) including the design and delivery of consumer messaging around the use of their data. It makes you wonder if users can ever truly know what they’re agreeing to.

Breaches and Bugs: Your Data Exposed

It’s one thing to begrudgingly, or obliviously, accept a privacy policy trade-off. But beyond this, how can users be sure their data will be secure? With recent data breaches in the health field such as MediSecure and Genea, concern for the privacy and safety of our most sensitive health data is ongoing. In fact, according to a recent OAIC Notifiable Data Breaches Report, health service providers ranked highest amongst the top five sectors to notify of breaches in the period.

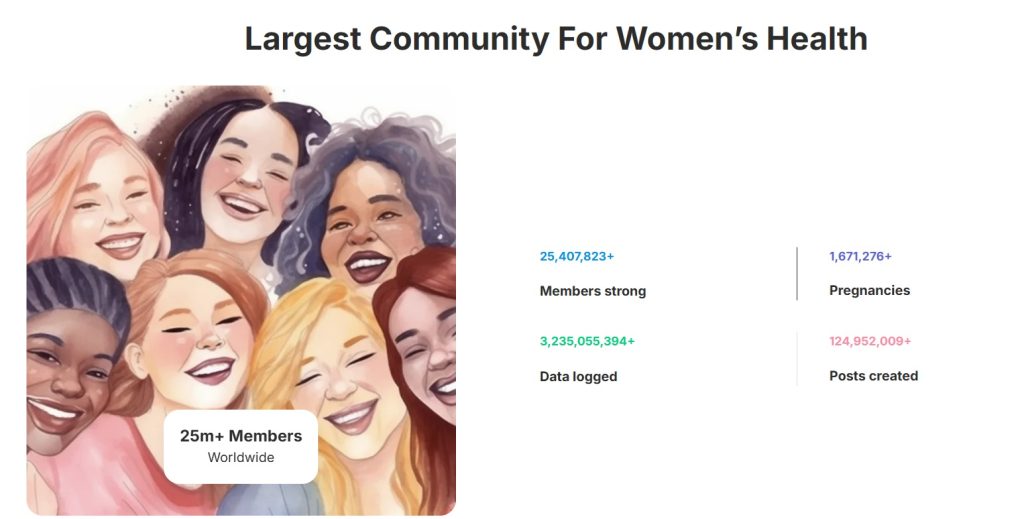

One platform in the FemTech space, Glow, lays claim to more than 25 million members worldwide. In 2024, reports emerged that the personal data of its entire user base had been exposed through a bug in the platform’s online forum. This included first and last names, age, location, user-uploaded photos and the app’s unique user identifier. Not only this, the bug was only addressed by Glow once a security researcher reported the issue to the company. Reportedly, Glow also did not publicly comment on the issue, including confirming whether or not users would be advised, other than to say that the bug had been ‘fixed’.

This wasn’t Glow’s first data-breach-rodeo. In 2016 a privacy loophole left user data vulnerable to third parties via the ‘Connect Partner’ feature. In 2020, an investigation by the California Attorney General regarding the lack of adequate protection of user data led to Glow paying a $250,000 fine. And yet, even after copping this fine, four years later it seemed Glow’s users still couldn’t rely on the platform to adequately protect their data.

Kemp (2023) also takes issue with platform data retention practices and lack of de-identification standards. Her research showed many apps appeared to keep data for lengthy periods under unclear disposal or deletion policies, leaving them more susceptible to breaches. And, while platforms often claim to ‘de-identify’ user data, there was a lack of clarity and enforcement around this being truly ‘anonymised’ versus being simply ‘pseudonymised’, with questions about the ability to easily re-identify such data or identify through aggregation with other data.

Inherently Vulnerable?

Due to the nature of digital platform architecture, they may be inherently vulnerable places for sensitive data. Designed by private companies, they are highly variable, subject to the technical issues around updates, differing levels of encryption and susceptibility to bugs. These apps also typically sit on a user’s personal mobile device adjacent to other “mobile resources” including contact lists, camera, microphone and location information, so it’s not just the data input into the app that could be at risk (Hofmann, 2024).

Reproductive Rights and “Bodily Data”

One of the other challenges for privacy, personal data and platforms is the global nature of digital technologies. The case of menstrual and fertility tracking apps presents unique questions about reproductive rights too, with troubling implications for users in parts of the world where abortion is restricted or banned.

Hammond and Burdon (2024) point to period trackers being part of a ” growing commodification of women’s bodies and their bodily data” (p.10) adding a gendered aspect to the “digital self-tracking” (Flew, 2021) of contemporary life.

Dylan Hofmann (2024) places conversations about FemTech in the context of reproductive rights, bodily autonomy and human dignity more broadly. He notes the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) which recognises the right to make ‘free and responsible’ decisions about having children as well as the right to have access to the “information, education and means to enable them [women] to exercise these rights” (Hofmann, 2024, p.470). He also refers to the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) which recognised “reproductive rights as human rights” including access to reproductive health and “post-abortion care regardless of the regulations in force” (Hofmann, 2024, p.470).

In some ways, perhaps FemTech apps could play a role in access to ‘information and education’ about an individual’s reproductive health, potentially aiding pregnancy prevention or planning. But, when mediated by privately owned platform businesses, this muddies the waters.

Prosecuting Pregnancy: Your Body On Trial

The kinds of specific regulations and laws that apply to medical information, such as HIPAA in the US, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which protects medical information collected by a healthcare provider (Hofmann, 2024), do not necessarily apply to the data collected by platforms such as period trackers.

The consequences of interacting with FemTech apps can also, in some cases and in some places, be extremely serious. In 2022 the US Supreme Court overturned the Roe v. Wade decision removing the constitutional right to abortion in the US and delegating decisions regarding abortion to each State. Abortions are heavily constrained or banned in several states, with some enforcing civil and criminal penalties. This caused understandable concern about whether menstrual or fertility tracking platforms may be obliged to surrender information about users’ pregnancy status to authorities.

US companies, in particular, may be legally compelled to provide this data. According to Lucie Audibert, a lawyer at Privacy International quoted in The Guardian, even if an app is based in, say, Europe and covered by Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), it’s common for European companies to comply with legitimate legal requests from US authorities. There have certainly been past examples where information gleaned from internet browsing history has been used as evidence. In 2017, a Mississippi woman was charged with second-degree murder after seeking medical attention for a pregnancy loss. Her internet searches were used as evidence in the case in attempt to show she sought to induce a miscarriage. An app detailing a user’s pregnancy status, and perhaps geolocation data to show if someone travelled to another state to obtain an abortion, could feasibly be used as evidence to pursue charges, enabling their use as a tool of ‘abortion surveillance’ (Ortutay, 2022).

Fertile Ground for Improvement

The case of FemTech’s period and fertility apps illustrates the need to navigate how intimate health data interacts with platform ecosystems and how privacy regulations are enforced globally. Platform companies seem to routinely escape impactful regulation, or, are not adequately disincentivised for unsafe practices. Considering the power of platforms to make the rules and the limits of individual agency, what can be done about concerns about privacy, data security and the legal implications of using menstrual and fertility apps? Requiring apps that deal with intimate health data like menstrual and fertility information to protect it in line with other health information could be an initial step.

Currently, the onus appears to be on the individual to engage with specific app privacy policies and make risk assessments within their national setting. But there are clearly limits to this. Until platforms are obliged to do more, and more fit for purpose regulations become available, this seems to be the only option. That, or giving FemTech apps the flick in favour of a good old-fashioned paper diary.

REFERENCES

Beilinson, J. (2020, September 17). Glow Pregnancy App Exposed Women to Privacy Threats, Consumer Reports Finds. Consumer Reports. https://www.consumerreports.org/electronics-computers/mobile-security-software/glow-pregnancy-app-exposed-women-to-privacy-threats-a1100919965/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity.

Franceschi-Bicchierai, L. (2024, February 13). Fertility tracker Glow fixes bug that exposed users’ personal data. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2024/02/13/fertility-tracker-glow-fixes-bugs-that-exposed-users-personal-data/

Garamvolgyi, F. (2022, June 28). Why US women are deleting their period tracking apps. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/28/why-us-woman-are-deleting-their-period-tracking-apps

Global Market Insights. (2025) Femtech Market. Retrieved 27/03/2025. https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/femtech-market

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., Bailo, F. (2017). Digital Rights in Australia. University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587.

Goode, L. (2016, July 28). Fertility app Glow warns users of security loophole. The Verge.

https://www.theverge.com/2016/7/27/12299178/glow-fertility-app-max-levchin-security-loophole-issues-fix

Hammond, E. & Burdon, M. (2024). Intimate harms and menstrual cycle tracking apps. Computer Law & Security Review, 55, Article 106038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2024.106038

Hofmann, D. (2024). FemTech: empowering reproductive rights or FEM-TRAP for surveillance?. Medical Law Review, 32 (4), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwae035

Kemp, K. (2023, March). Your Body, Our Data: Unfair and Unsafe Privacy Practices of Popular Fertility Apps. University of New South Wales. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4396029

Lavoipierre, A. (2024, July 18). MediSecure reveals 12.9 million Australians had personal data stolen in cyber attack earlier this year. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-07-18/medisecure-data-cyber-hack-12-million/104112736

Lu, D., Taylor, J. (2025, February 26). Sensitive details of Australian IVF patients posted to dark web after Genea data breach. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/feb/26/genea-data-breach-hack-ivf-patient-details-leaked-ntwnfb

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831-852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. (2025). Australian Privacy Principles. Retrieved 31/03/2025. https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/australian-privacy-principles

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. (2025). Notifiable Data Breaches Report: January to June 2024. Retrieved 31/03/2025. https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/notifiable-data-breaches/notifiable-data-breaches-publications/notifiable-data-breaches-report-january-to-june-2024

Ortutay, B. (2022, Jun 28). Why some fear that big tech data could become a tool for abortion surveillance. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/why-some-fear-that-big-tech-data-could-become-a-tool-for-abortion-surveillance

Suzor, N.P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules?. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives (pp. 10-24). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Totenberg, N., McCammon, S. (2022, June 24). Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, ending right to abortion upheld for decades. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1102305878/supreme-court-abortion-roe-v-wade-decision-overturn

VanScoy, A., Gates, H. (2024, March 18). Growing femtech investment brings solutions to underserved women’s health challenges. Deloitte Blog: The Pulse. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/blog/accounting-finance-blog/2024/femtech-growth-investment.html

Be the first to comment