Have you ever noticed that the content you come across on social media is becoming more and more extreme? If you have such a feeling, it’s not surprising at all. Many users have found, to their confusion, that once they like a radical post, there seems to be even more similar content in their subsequent news feeds. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have sophisticated recommendation algorithms behind them. These algorithms will determine what content to present next based on your every like, share, and even the amount of time you spend on a post.

Although these companies claim that their original intention is to let the audience see posts that they are more interested in, does this mechanism unconsciously fuel the spread of hate speech? In Australia, this is not just a baseless assumption. For example, during a recent general election, offensive remarks targeting ethnic minorities flooded social media platforms. Also, false information about the refugee issue once spread wildly online, causing social divisions and controversies.

This blog post will explore how social media algorithms affect the spread of hate speech and use real cases from Australia to illustrate this impact. Finally, it will discuss possible solutions to this problem.

Nowadays, social media platforms use recommendation algorithms to determine the content that users see. Such algorithms are user-data-oriented and aim to provide personalised news feeds. They take into account users’ interests and preferences, such as the content they have liked, the topics they follow, their past interaction behaviours (data on browsing, commenting, and sharing), as well as social connections (popular posts in the friend network, etc.), and filter out the content that “users are most likely to be interested in” from a vast amount of information for pushing (Just & Latzer, 2017).

Essentially, this algorithm mechanism is an engagement optimisation model: the platform continuously learns from users’ behaviours to predict and recommend content that suits their tastes, thereby enhancing user stickiness (Crawford, 2021). For example, every time a user likes or stays to view a certain type of post, it is unconsciously training the algorithm to tend to present more similar content. This design is intended to extend the user’s online stay time so as to maximise the platform’s engagement indicators and the exposure of advertisements (Just & Latzer, 2017; Flew, 2021).

At the same time, it is necessary to clarify the definition and dissemination characteristics of hate speech on social media. Generally speaking, hate speech refers to offensive and derogatory remarks made about other groups based on identity characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and political stance (Sinpeng et al., 2021). Such remarks often carry a strong discriminatory colour and hostility, and their harm lies in attempting to marginalise the target group and deprive them of the right to participate equally in social discussions. It can be imagined that in such a social media environment, hate speech has highly emotional and inflammatory characteristics. They may be filled with posts containing racial hatred or gender discrimination at any time, often triggering strong reactions such as anger or fear among users.

To further illustrate, there are cases around the world where social media platforms have led to disastrous consequences due to algorithms amplifying extreme remarks. For example, in countries such as Myanmar and India, there have been incidents where social media incited violence against minority groups. These incidents have triggered strong criticism from the international community regarding the platforms’ indulgence of hateful content (Sinpeng et al., 2021). It is worth noting that the business models of social media platforms largely influence the algorithms’ tendency to boost hate speech. Mainstream social media platforms mainly rely on advertising revenue as their source of profit, and advertisers often favour platforms that can attract users’ attention for a long time (Crawford, 2021). Therefore, platforms have an economic incentive to maximise user engagement in order to display more advertisements.

Emotionally intense and polarised content (including hate speech), although harmful, often catches users’ attention more effectively and drives interactions. This, invisibly, brings traffic and profits to the platforms (Flew, 2021). Algorithms are not deliberately designed to favour hateful content, but under the rules oriented towards click-through rates and viewing durations, such “high-engagement” posts will be preferentially recommended to users.

Nevertheless, compared with other platforms, TikTok’s recommendation algorithm is particularly aggressive and sensitive, which makes it possibly more prominent in spreading hateful content. Therefore, this article will next focus on exploring the uniqueness of TikTok.

As an international student from China, when I used TikTok in Australia, I deeply felt the power of its algorithm. Once I opened the app, the “For You” recommended video stream on the homepage seemed to be tailor-made for me. With its precise recommendations and the design of endless scrolling, TikTok can easily attract users to immerse themselves in it for a long time. According to statistics, TikTok users spend an average of 34 hours per month on the platform, which is higher than that of other social media, demonstrating its extremely high user stickiness and attractiveness (Idris, 2024).

This algorithm-driven immersive experience has made TikTok the main source of information and entertainment for many young people, and Australia is no exception. More than 8.5 million Australians use TikTok, making it the “default platform” for young people to obtain information (Touma, Bogle, & Evershed, 2023). During my daily browsing, I also found that without the need to follow specific accounts, the TikTok algorithm will continuously push content that interests me based on my viewing time and interaction behaviors. This powerful recommendation engine brings both fun and hidden risks. When the algorithm blindly caters to users’ interests, is it also unconsciously guiding us into an information cocoon and even pushing hate speech in front of our eyes?

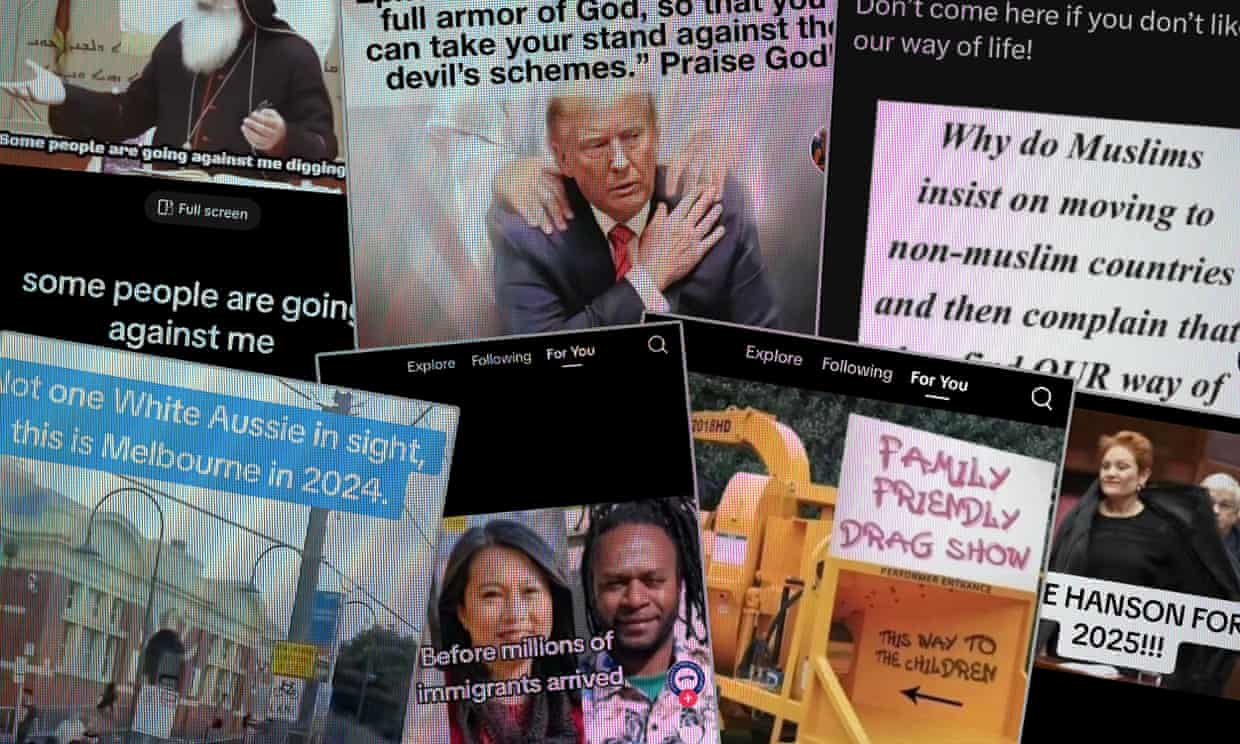

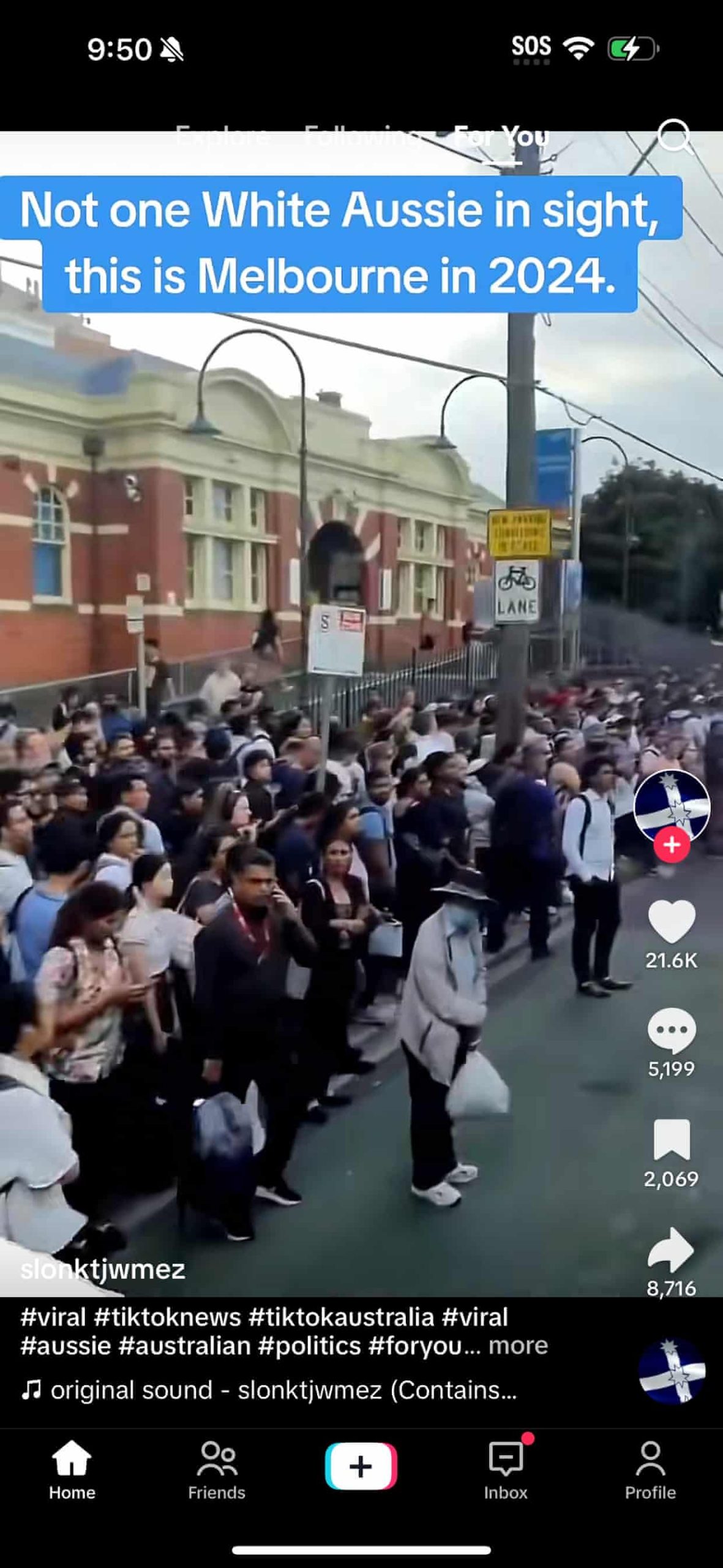

In reality, TikTok’s algorithm does have the potential to boost the spread of extreme or hateful content in Australia. A typical case is the experiment conducted by The Guardian Australia in 2024: Researchers created a brand-new blank TikTok account and observed the recommended feed without liking or commenting on any content. In the first two days, the account mostly saw ordinary content such as daily videos related to Melbourne, the location where it was set, and mobile phone tips.

However, a knife attack incident that transpired in the Sydney suburbs in mid-April marked a pivotal moment. When the experimental account watched several news videos about the incident, TikTok’s algorithm was quickly “activated”—more” videos of conservative Christian sermons began to flood the recommendation page, which then evolved into a continuous stream of conservative content (Taylor, 2024).

In the following three months, even though the user still did not actively like any videos, the algorithm continued to reinforce this tendency: A large number of videos with far-right tendencies appeared on the recommendation page, including content supporting far-right politicians in Australia and former U.S. President Donald Trump, as well as posts with strong anti-immigrant and anti-LGBTQ tendencies. There were even extreme hate speeches inciting violence, such as suggesting throwing drag performers into a woodchipper (Brown, 2024).

This case clearly shows that TikTok’s recommendation algorithm can lead users into a “rabbit hole” full of hatred and prejudice in a very short period. Disturbingly, this transformation is almost entirely based on very few hints of the user’s interests — just by watching the relevant videos, the algorithm inferred that the user might “like” such content and aggressively recommended similar videos.

It’s not just in Australia; the phenomenon reflected in this case has occurred frequently around the world. TikTok claims to have strict policies regarding hateful content, but the enforcement often lags. Research conducted by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford indicates that although TikTok explicitly prohibits harmful content such as hate speech, the implementation is inadequate, and many videos that clearly violate the rules remain on the platform for an extended period (Kumar, 2023).

For instance, during Malaysia’s general election in 2022, many clips related to the ethnic riots in 1969 were widely disseminated on TikTok, triggering hate speech directed at Chinese political parties and leaders of non-Malay ethnic groups. Relevant hashtags trended on the platform for several days (Kumar, 2023). These messages filled with racial hatred attracted significant attention on TikTok, and it even led to the Malaysian government summoning TikTok for discussions and demanding rectification (Kumar, 2023). It is evident that, whether in Australia or other countries, TikTok’s algorithm-driven recommendation mechanism has the potential to expand the reach of hate speech within a short period and expose extreme views to a broader audience.

The above cases highlight the “interest trap” effect of TikTok’s algorithm — once users show even the slightest interest in a certain type of content, the algorithm will quickly increase the frequency of recommending more similar content. I have personally experienced this algorithmic bias: Once, out of curiosity, I watched a complaining video laden with racial stereotypes. In the following days, the home page started pushing more similar complaints and controversial remarks, which greatly bothered me.

This amplifying effect based on interest signals means that users’ initial viewing behaviours (even without liking the content) will be regarded as preferences by the algorithm, thus continuously increasing the exposure of homogeneous content. TikTok’s recommendation algorithm is more proactive and sensitive than those of platforms like Facebook and Instagram. It judges users’ interests based on implicit interactions such as the duration of stay and repeated viewings (Taylor, 2024).

As scholars have said, TikTok’s technical mechanism enables it to “push users towards extreme content very quickly” (Touma et al., 2023). On the one hand, this mechanism ensures that we see content that we are interested in; on the other hand, it also easily traps people in a single information domain, causing them to cycle repeatedly. When it comes to hate speech, the interest trap can magnify people’s inner prejudices: after watching an inflammatory short video, users may be continuously pushed with more extreme remarks and unconsciously form a radical worldview.

TikTok’s algorithm not only takes into account individual interests but also amplifies group-based interaction feedback. On TikTok, videos that receive a large number of likes, comments, and shares are often recommended to more users. The original intention of this design is to capture “trending” content across the entire platform, but it may have a magnifying effect on hate speech.

For international students like me, the content mismatch brought about by TikTok’s algorithm can sometimes be quite impactful. When browsing TikTok in Australia, I often come across content related to China or with an Asian background: some are patriotic short videos posted by Chinese creators, while others are funny videos shot by local Australian users imitating East Asian culture. The contextual mismatch of cross-cultural content under algorithmic recommendations can easily lead to misunderstandings and even conflicts.

For example, when I came across a video from China in Sydney that expressed a nationalistic stance on a certain international event, I felt mixed emotions. On the one hand, this voice was close to my cultural background, but on the other hand, when reading the comments in the Australian context, I often saw the local netizens showing disapproval or even strong opposition. This sense of disconnection made me clearly realise that the same TikTok content being pushed by the algorithm in different cultural circles may trigger completely opposite interpretations and reactions.

Similarly, jokes related to Chinese culture posted by local creators for the sake of humour may seem offensive or even prejudicial to Chinese international students. However, TikTok’s algorithm does not understand these subtle cultural differences and will only continue to recommend similar videos based on interaction data. For international students in a foreign country, seeing content related to their home country being taken out of context and spread on TikTok often makes them feel misunderstood or offended. This experience has led me to reflect: algorithmic recommendations lack cultural sensitivity. When similar content is being disseminated across cultures, the “blind neutrality” of the algorithm may instead deepen ethnic stereotypes and antagonistic emotions. If the platform does not take measures, TikTok is likely to inadvertently act as an amplifier of cross-cultural conflicts.

Facing the issue of algorithms boosting hate speech, TikTok cannot shirk its own responsibilities. TikTok’s official side has repeatedly reaffirmed that its community guidelines prohibit content related to hatred and harassment and has invested a large number of resources to improve the content moderation mechanism. An example would be TikTok claimed that it would invest 2.9 billion Australian dollars globally in the field of trust and security in 2024 and has used AI technology to automatically remove 80% of the content that violates the rules (Australian Broadcasting Corporation [ABC], 2024). The platform also provides some user autonomy options, such as long-pressing a video and selecting “Not Interested” to reduce similar recommendations (Taylor, 2024).

In conclusion, TikTok’s personalised algorithm may unwittingly boost hate speech, especially in multicultural Australia. To tackle this, TikTok should make technical and policy improvements. It could adopt Twitter’s 2023 real-time rate-limiting to kerb hate-content spread and optimise its AI system for preemptive intervention. Australian regulators should expand the eSafety Commissioner’s powers and collaborate with TikTok to set up clear accountability mechanisms. Users, too, should understand algorithms better and use reporting and blocking tools. Only through joint efforts can TikTok stop promoting hate speech, becoming a cross-cultural bridge instead.

References List

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). (2024, October 12). TikTok slashes hundreds of jobs to help boost AI-assisted content moderation. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-10-12/tiktok-slashing-jobs-to-boost-ai-content-moderation/104465606

- Brown, D. (2024, July 27). TikTok’s algorithm is highly sensitive and could send you down a hate-filled rabbit hole before you know it. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/27/tiktoks-algorithm-is-highly-sensitive-and-could-send-you-down-a-hate-filled-rabbit-hole-before-you-know-it

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

- Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

- Idris, I. (2024, August 8). Deceptive trends: The societal impact of disinformation on TikTok. Australian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/deceptive-trends-the-societal-impact-of-disinformation-on-tiktok/

- Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

- Kumar, R. (2023, August 21). Hate speech can be found on TikTok at any time. But its frequency spikes in elections. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/hate-speech-can-be-found-tiktok-any-time-its-frequency-spikes-elections

- Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific (Report). University of Sydney & University of Queensland.

- Taylor, J. (2024, July 26). TikTok’s algorithm is highly sensitive—and could send you down a hate-filled rabbit hole before you know it. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/jul/27/tiktoks-algorithm-is-highly-sensitive-and-could-send-you-down-a-hate-filled-rabbit-hole-before-you-know-it

- Touma, R., Bogle, A., & Evershed, N. (2023, September 18). No campaign spreads through TikTok ‘like wildfire’ as pro-voice creators struggle to cut through. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/sep/19/indigenous-voice-to-parliament-referendum-no-campaign-tiktok

Be the first to comment