Introduction

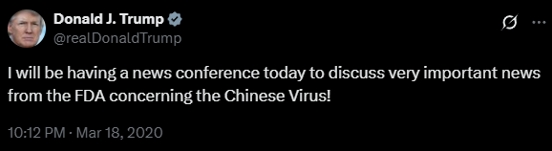

The 2021 Atlanta spa shootings resulted in the deaths of eight people, six of which were Asian women (Honderich, 2021). This tragedy has caused serious concern and panic of anti-Asian hate crimes within the Asian community. A very important thing to figure out is where does this Asian hate come from? President Trump has been referring to COVID-19 as the “China Virus” since 2020, and has used this racially phrase more than once on Twitter and in public appearances (see Figure 2). Although international health officials have intentionally avoided linking geographic locations to the virus, Trump still continues to link China to COVID-19 (Reja, 2021). This association of a virus with a minority group could increase the spread of racism in society. In an interview with Christopher Chan of the Asian American Fund’s Georgia Chapter, we can tell that the Trump administration’s inappropriate speech during the COVID-19 is leaving Asian Americans to suffer consequences (Jung, 2021). This anti-Asian hate speech from America’s top leader has been more widely spread through social media platforms like Twitter, thus turning it into a stronghold of Asian hate. Hostile comments against Asians on Twitter spiked 85% just three days after Trump’s COVID diagnosis (Dwoskin, 2020). In this process, Twitter’s algorithms have played a tool in fueling the growth of hate speech. Dr. Daniel Rogers of New York University suggests that platform’s algorithms recommend increasingly extreme content to users who are interested in hateful content, thereby motivating users with violent tendencies to commit hate crimes (Reja, 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to request popular social media platforms, such as Twitter, to improve their algorithms to reduce the spread of hate speech on the platform in order to protect those minority groups.

What Is Hate speech?

Hate speech is defined as the expresses, encourages, stirs up of hatred against a specific group of people, it generates mistrust and hostility in society, and the victims are unable to relax and live a life without fear and harassment (Flew, 2021). Hate speech would take place in public, both online and offline, and the public can be unintentionally exposed to it (Sinpeng et al., 2021). For major social media platforms such as Twitter, they become a kind of public place that hosts the spread of public discourse. This article argues that Twitter needs to take responsibility for the content of hate speech posted by its users. Twitter defines Hateful Conduct as direct attacks on others based on characteristics such as race, gender, religion, and disability, and it regulates hate speech by reducing its visibility or requiring users to delete posts (X, 2023). This can possibly lead to platforms with unclear regulations on hate speech, overly casual application of rules, and lack of clarity on who and what will moderate the content (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

How Does Twitter algorithm Fuels Hate speech?

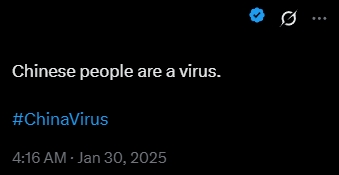

Twitter does not have the power to directly delete inappropriate speech based on respect for free speech, and Twitter’s algorithms do not fully moderate all posts that may involve hate speech. Especially in terms of hate speech against Asians, automated systems can differ on the definition of hate speech, allowing them to avoid regulation (Toliyat et al., 2022). Algorithms also have the potential to increase the spread of hate speech. Users who are exposed to hate speech will be exposed to more hate speech or even join in the spread of speech in future posts, thus reaching an “echo chamber effect” (Wheeler et al., 2023). This has resulted in a large number of racial attacks against Chinese and Asians in #ChinaVirus. What’s worse, we can still see COVID-based hate speech against Asians on Twitter even in 2025 (see Figure 3). This may show that Twitter’s moderation algorithms for hate speech have not improved over the years. According to Hickey et al. (2025), the average number of hate speech posts on Twitter per week increased by 50% after Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, and it is possible that the algorithms are unintentionally promoting hate speech to users who like such content. Twitter needs to pay more attention to how hate speech is spread on its platform and make improvements to its moderation algorithm.

Case Study: Asian Hate During COVID-19 Pandemic

As mentioned above, all discriminatory speech against Chinese and the Asian community in Twitter’s #ChinaVirus can be considered anti-Asian hate speech. As shown in the example in Figure 4 above, the hate speech against Asians in #ChinaVirus is mainly reflected in the strong connection between the virus and Asians, and the belief that Asians “purposely” spread the virus to various countries. Meanwhile, the discriminatory slogan “Go back to China” also represents the denial of the local identity of Asians. Kim and Sundstrom’s research (2014) explain this xenophobia as that some Americans believe that Asian Americans are irrelevant to the U.S. This devaluation is reinforced in times of crisis, with the belief that these “threatening” people don’t belong here. This discriminatory idea thus becomes hate speech on social media platforms in the Information age. COVID-19 pandemics can even further increase prejudice and xenophobia, as evidenced by racist sentiments on social media platforms (Wei et al., 2024). This hate speech also labeling all Asians as Chinese, thereby denying the independence of other Asian peoples. This denial of identity to the victims could undermines their self-esteem (Odağ & Moskovits, 2025).

The exclusion and hatred of Asians caused by hate speech is not limited to the Internet, the attacks have been transferred from online to the real world (Odağ & Moskovits, 2025). Since March 2020 through the summer of that year, there have been 2,120 hate incidents against Asian Americans in the United States (Dwoskin, 2020). It can be argued that the continued spread of hate speech on Twitter increases the risk of hate crimes against Asians and ultimately leads to tragedies like the 2021 Atlanta shootings. For example, in New York City, there was a significant increase in the number of hate crimes against Asians beginning in March 2020, peaking in March 2021, and for every 1% increase in negative sentiment against the Asian community on Twitter, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes in New York City increased by 24% (later adjusted to 16%) in the same month (Wei et al., 2024). Twitter’s algorithms failed to stop the spread of hate speech during the COVID-19 pandemic, and instead made Twitter a tool for spreading extreme racist ideology. As Dr Matamoros-Fernández (2017) argues, the underlying infrastructure of social media platforms has become contributing to racism in addition to growing their economic interests.

What Happened to Anti-Hate Content?

On the other hand, there was little discussion of anti-hate content in the early days of the epidemic, which led to the result that Twitter’s algorithms would not support the spread of anti-hate content to counter hate speech. The frequency of anti-hate keywords was low until September 2020 and only began to rise significantly in February 2021, which could be a response to hate crimes against Asians (Wheeler et al., 2023). It is clear the algorithm tends to spread hate speech on Twitter to evoke racist sentiments thus triggering more users to engage, that is why Asian hate content is shown to more users rather than anti-hate content.

What Needs to Change?

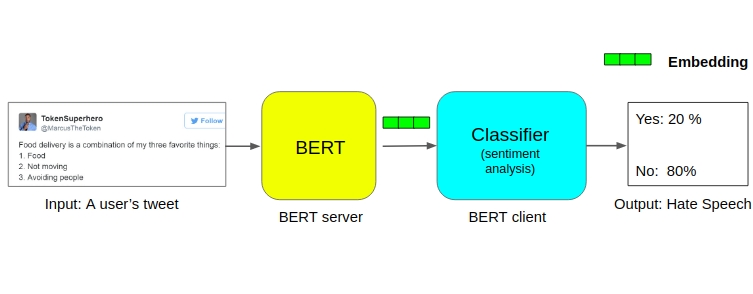

Anti-Asian hate speech is largely linked to Twitter’s content moderation algorithm. So the easiest and most direct way to reduce or even completely eliminate hate speech is to upgrade and improve Twitter’s algorithms. According to recent research by Toliyat et al. (2022), they found that the BERT model performed the best among multiple moderation algorithms in identifying and classifying 1,901 tweets about hate speech. From this social media platforms could build a new set of hate speech moderation frameworks with new algorithms similar to the BERT model, which could be a way for Twitter to improve its moderation algorithms. In addition to this, Twitter should be responsive to hate speech reported by users and provide feedback and results in a timely manner. Users are sensitive to the results of reporting content, and if the platform fails to give users a satisfactory outcome, it can cause them to stop using the reporting function, thus allowing hate speech to go free on the platform. In Odağ and Moskovits’ research (2025) we can learn that users are doubtful and frustrated about the usefulness of the platform’s reporting function, and that the lack of platform support and the echo chamber effect as well as filter bubbles prevent users from engaging in discussions.

To complement the user reporting function, Twitter needs to improve the quality of identification by human moderators, and the platform needs to recognize the role of page administrators as key gatekeepers of hate speech content and support them in improving their regulatory literacy through training and education (Sinpeng et al., 2021). In the case of hate speech against Asians, much of the discriminatory content may be overlooked by administrators due to cultural and linguistic differences, resulting in the fact that even user-reported hate speech may be ignored by the moderation system.

In addition to platform self-regulation, the government can also be involved to a certain extent in the moderation and governance of social media platforms, thereby reducing the possibility of hate crimes occurring. Germany’s NetzDG, which came into force in 2017, requires social media platforms with more than 2 million German users to respond to user complaints by deleting obviously illegal hate speech and other illegal content within 24 hours (Kohl, 2022). This can make social media platforms legally responsible for regulating hate speech and increase the efficiency and accountability of the platforms, thus effectively stopping the spread of hate speech on social media.

Conclusion

All in all, hate speech and baseless accusations against Asians have been spreading on Twitter since President Trump brought up the “China Virus.” This hate speech can cause a very serious mental health issue for the Asian community. Those who publish hate speech deny Asians local identity by motivating public to be xenophobic, and they also undermine the self-esteem and identity of Asians by uniformly labeling all Asians as Chinese. And it has been shown through a series of studies that there is a strong connection between this widely spread anti-Asian hate speech and real hate crimes against Asians.

This article therefore argues that popular social media platforms, such as Twitter, should be held responsible for the spreading of hate speech in order to achieve the protection of the mental health and physical safety of minorities under racist attack. Twitter’s algorithm still hasn’t managed to completely deter the emergence of anti-Asian hate speech until 2025. We therefore advocate that Twitter can improve its moderation algorithm, pay more attention to the reporting function, improve the literacy of its human moderators, and cooperate with government legislation in order to effectively identify and moderate hate speech.

References

Anonymous [@anonymous]. (2020, March 19). Anti-Asian tweet during early COVID-19 outbreak [Tweet screenshot, anonymized by author]. X (formerly Twitter). https://x.com/lmyau1/status/1240321362184400896

Anonymous [@anonymous]. (2025, January 30). Anti-Asian tweet after COVID-19 pandemic [Tweet screenshot, anonymized by author]. X (formerly Twitter). https://x.com/TameDoe/status/1884651936911073491

Dwoskin, E. (2020). When Trump gets coronavirus, Chinese Americans pay a price. The Washington Post.

Flew, Terry (2021) Hate Speech and Online Abuse. In Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 91-96

Hickey, D., Fessler, D. M. T., Lerman, K., & Burghardt, K. (2025). X under Musk’s leadership: Substantial hate and no reduction in inauthentic activity. PloS One, 20(2), e0313293-. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0313293

Honderich, H. (2021, March 20). Atlanta spa shootings: How we talk about violence. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56446820

Jung, C. (H. S.). (2021, March 18). Asian Americans fearful after Georgia massage parlour shootings. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/georgia-shooting-hate-crime-1.5954300

Kim, D. H., & Sundstrom, R. R. (2014). Xenophobia and Racism. Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.2.1.0020

Kohl, U. (2022). Platform regulation of hate speech – a transatlantic speech compromise? The Journal of Media Law, 14(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/17577632.2022.2082520

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/136918X.2017.1293130

Odağ, Ö., & Moskovits, J. (2025). We are not a virus: repercussions of anti-Asian online hate during the COVID-19 pandemic on identity and coping strategies of Asian-heritage individuals. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 48(2), 368–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2024.2362459

Reja, M. (2021, March 18). Trump’s ‘Chinese virus’ tweet helped lead to rise in racist anti-Asian Twitter content: Study. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/trumps-chinese-virus-tweet-helped-lead-rise-racist/story?id=76530148

Rizvi, M. S. Z. (2024, October 15). BERT: A comprehensive guide to the groundbreaking NLP framework. Analytics Vidhya. https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2019/09/demystifying-bert-groundbreaking-nlp-framework/

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final Report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. Dept of Media and Communication, University of Sydney and School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland.

Stevens, A., & Abusaid, S. (2022, March 16). Atlanta spa shootings: 1 year later, families rebuild, await justice. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/crime/atlanta-spa-shootings-1-year-later-families-rebuild-await-justice/63IRIVPFJ5COLN32LCTRLRDNHI/

Toliyat, A., Levitan, S. I., Peng, Z., & Etemadpour, R. (2022). Asian hate speech detection on Twitter during COVID-19. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 5, 932381–932381. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2022.932381

Trump, D. [@realDonaldTrump]. (2020, March 18). I will be having a news conference today to discuss very important news from the FDA concerning the Chinese Virus! [Tweet]. X (formerly Twitter). https://x.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1240234698053431305

University of Michigan School of Public Health. (2022, May 31). Asian American protesters wearing masks and holding signs [Image]. University of Michigan School of Public Health. https://sph.umich.edu/news/2022posts/asian-americans-armed-themselves-during-pandemic-in-response-to-racial-acts.html

Wei, H., Hswen, Y., Merchant, J. S., Drew, L. B., Nguyen, Q. C., Yue, X., Mane, H., & Nguyen, T. T. (2024). From Tweets to Streets: Observational Study on the Association Between Twitter Sentiment and Anti-Asian Hate Crimes in New York City from 2019 to 2022. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26(5), e53050-. https://doi.org/10.2196/53050

Wheeler, B., Jung, S., Hall, D. L., Purohit, M., & Silva, Y. (2023). An Analysis of Temporal Trends in Anti-Asian Hate and Counter-Hate on Twitter During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 26(7), 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0206

X. (2023, April). Hateful conduct policy. X Help Center. https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy

Be the first to comment