We all know that social platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have become the main channels for modern people to obtain information. But have you ever thought that the content that seems to be “recommended to you” on these platforms is not so neutral? Especially during the US presidential election, the algorithm does not only tell you what news your friends are watching, it may be secretly influencing your political thoughts, and even make you mistakenly believe that “everyone thinks so.” This is not a conspiracy theory, but a fact revealed by more and more scholars and surveys: AI and algorithmic technology are changing the rules of the political game in ways that we cannot detect. From the 2016 US presidential election that shocked the world, in addition to the fierce confrontation between presidential candidates, the real influence behind voters’ decisions may be the social media they see every day. From Facebook’s recommendation algorithm to political speeches on Twitter, the AI technology behind these platforms is quietly changing the rules of the game in political elections. Companies like Cambridge Analytica use huge user data to accurately push political advertisements on Facebook, quietly manipulating voters’ judgments, and AI uses algorithms to push “micro-targeted advertisements” to millions of users, tailoring a whole set of political propaganda to users (The Guardian, 2018). This behavior sounds like high-tech, but it actually reflects a core problem: AI systems are not just tools, they are new power structures, and they are “invisible governments” that can determine what we see and believe. We are beginning to question again: Are AI and algorithms protecting democracy or redefining it? This article will take you to explore in depth: When algorithms participate in politics, what role do they play? I will analyze these issues in a simple and easy-to-understand way, and combine specific cases to uncover the “algorithmic democracy” hidden behind the screen.

Triple Weapons of Algorithms: Micro-targeted Advertising, Recommendation Systems, and Information Cocoons

How does AI manipulate our political choices? There are three key words that cannot be avoided: micro-targeted advertising, recommendation algorithms, and information cocoons. These three algorithms are like a triple filter, pushing users layer by layer into an information world “planned” by algorithms, and users generally don’t notice it.

1. Micro-targeted advertising: Influencing you like a “political psychologist”

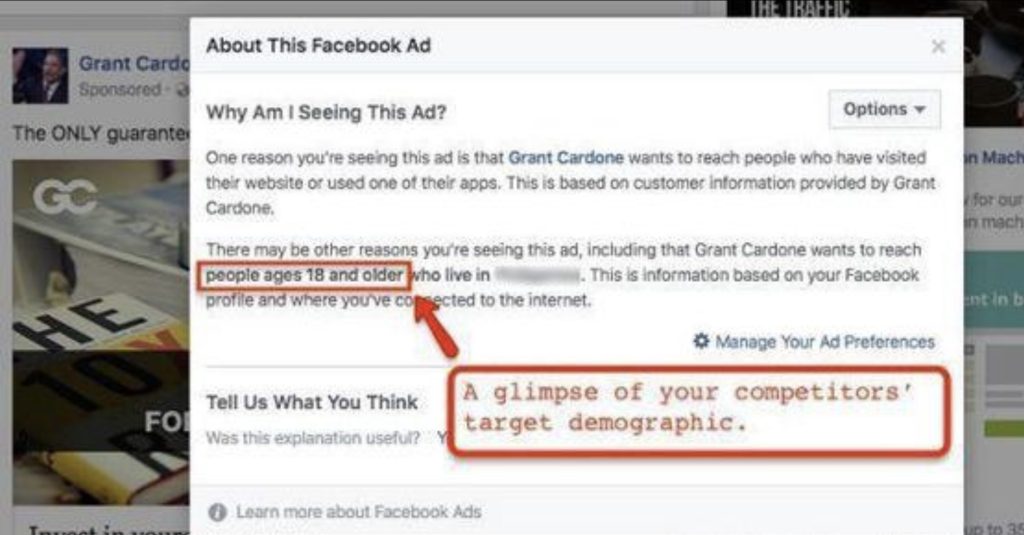

The word microtargeting sounds a bit technical, but the logic of this algorithm is very simple: it is to accurately place advertisements by analyzing your data, and only place content you are willing to see.

Crawford (2021) proposed a very strong metaphor: AI is not a mirror, but a map. Because the map is not the whole of reality, but selectively presents certain places, ignores certain details, and plans the map according to the intention of the cartographer. Similarly, AI systems are also drawing an “information world map” to tell users “what is important and what is not worth seeing.” In the 2016 US election, Facebook’s algorithm drew an “invisible map” of voter bias and psychological reactions based on user behavior. It is not a geographical map, but an emotional map, an interest map, and a political attitude map. Of course, these “maps” are not generated out of thin air, but are constructed through your daily browsing, likes, and comments. Facebook has the sole editing rights of this map and can choose to “zoom in” on a certain area or “ignore” certain voices at any time.

In the 2016 US election, Cambridge Analytica stole the Facebook data of more than 87 million people and used a small psychological test application to roughly determine whether a person is extroverted or anxious, optimistic or fearful. Then they segment users into different “emotional labels” based on these psychological characteristics (Maalsen, 2023). For example: If you are the kind of person who is easily worried about social order? Then you will receive more political content about rising crime rates and immigration threats; if you are the kind of optimistic liberal who is keen on the future development of the country? You will see how a candidate “leads the country back to glory.” These ads are not open to everyone, but are secretly pushed and only shown to you. You think you are “watching the news”, but in fact you are being manipulated. What’s more terrifying is that everyone sees a different version, which makes it impossible for us to discuss the same “reality” at all. The platform uses your data, emotions and behaviors to construct a “political narrative landscape” for itself. This is exactly what Crawford said: AI is essentially a registry of power rather than a neutral tool. Because AI is a “technological myth” built up by a large amount of data, manpower, energy and resources. AI embodies the desires and prejudices of a social-political system. Its essence is an epistemic machinery of knowledge that serves the existing power order, manipulates user thoughts rather than promotes democratic rationality, and is controlled by a few technology giants. In this case, the definition of “what is important, who is seen, and who is ignored” has obvious political orientation and power distribution.

Extended reflection:

Can we still share “a world of public facts”? If everyone’s map is different, can we still have a democratic discussion on a common reality?

2. Recommendation algorithm: The essence of the algorithm is to “cater to emotions”, when emotions become the fuel of election campaigns

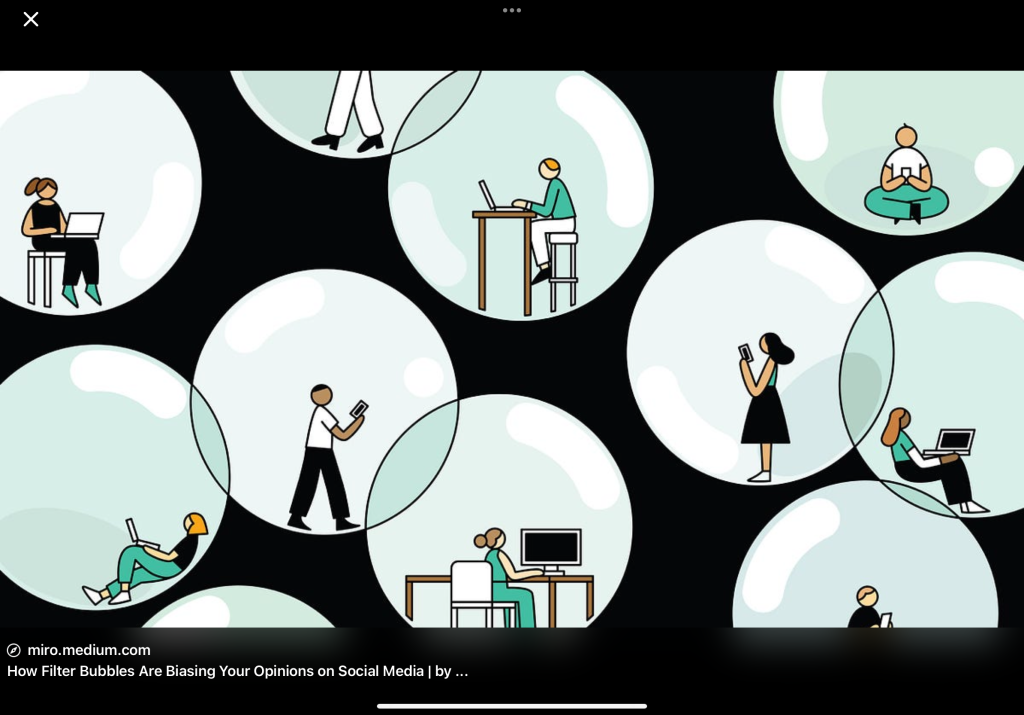

In addition to advertising, the way content is presented on social media is also quietly changing. The posts, videos, and articles that users see are not “random”, but the result of “careful selection” by algorithms. Platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have their own recommendation systems. The ultimate goal of the platform is not to let us see the “best” information, but to keep users staying longer and interacting more. How to do this? The answer is actually not difficult to guess: stimulate emotions. Because humans react most strongly to emotional content-angry speeches, provocative language, and exaggerated headlines. The platform analyzes your reaction and constantly pushes similar content to you. The angrier and more extreme you are, the faster you like, forward, and comment, the more certain it is: you like to see this style, so it continues to push, and the cycle continues. Those objective and neutral content are usually buried at the bottom of the recommendation list because they “will not make you react immediately.” In this way, the information we receive is no longer diverse and balanced, but increasingly emotional and extreme. Just and Latzer (2017) put forward a key point in their article: algorithms are not just filtering information, but constructing “reality.” They call it “reality construction by algorithmic selection.” This means that the platform not only tells you “what others are watching”, but also shapes what you think “the world is like.” Remember what your social media homepage looked like during the 2016 US presidential election? Overnight, effective users lived in a world surrounded by “Trump supporters”, or conversely, only saw news about “Hillary’s corruption” without a neutral perspective. Imagine: If everyone’s news feed is different, then we no longer live in the same political reality. What you see is “immigrants threaten national security”, and what I see is “Russian interference behind Trump”, and we are all sure that what we see is the truth. In this algorithmic world, we are not only becoming more and more extreme, but also losing the basis for discussion.

Example: Conservative and right-wing groups, as well as companies such as Cambridge Analytica, use algorithms to classify voters and then precisely deliver highly emotional content:

- Push fake news about “Mexican crime rates rising” to people who are sensitive to immigration;

- Push the message that “the political system is unfair to you” to the black community to encourage them to abstain;

- Push Hillary’s conspiracy theory of “attacking Christian values” to religious conservatives.

3. Information cocoon: The world you see is not the real world

Information cocoon is not just “not seeing”, but “living in a script written by others for you”.Many people think that the biggest problem with information cocoon is that users cannot see different voices. But the more terrible problem is that users do not realize that the content they see is designed by politicians. The logic of emotional sensitivity makes many people live in a highly emotional political script. And the authors of the script are those big platforms that make money from traffic. Couldry and Mejias believe that this is “automated culture”. Automated culture is not neutral, it is an invisible way of governance (Andrejevic, 2019). When we hand over the acquisition of information to the platform, “citizen discussion” gradually becomes “content consumption”. The platform determines what we see and ignore every day through algorithms. This is an informal form of power. We did not vote to authorize it, but it has been deeply involved in our political life. We have changed from public discussants to Internet users who quietly swipe the screen. When the information filtering system dominated by the platform dominates public discussion, the user’s “citizen” identity will gradually be replaced by “content consumer”. Because the platform turns politics into an emotion-driven attention economy game, and we are the objects that are pushed, manipulated, and classified. So if we give up questioning and intervening in these algorithmic rules, we will slowly give up the core of democratic society—commonality, citizenship, and collective imagination.

When governance cannot keep up with the speed of the algorithm, who will manage such a large platform?

After the 2016 US presidential election, many people began to question: Have social media platforms like Facebook become “invisible political machines”? How should we manage it?

Regulation has failed, and old rules cannot catch up with new technology

Many of the election regulation systems used by most countries are still in the era of radio and television. For example, the Federal Election Campaign Act in the United States stipulates that political advertising must be transparent and funding must be disclosed. But these rules are almost inapplicable to modern social media. Because political ads on Facebook are “invisible” rather than publicly placed, and are only “micro-targeted ads” pushed to specific groups of people. For example, if you are a 20-year-old African-American woman, go to school in the United States, and often like content about social injustice, you will receive a suggestive message of “abstaining for justice.” And her father may be a promotional video of “Trump is the last hope of the country.” Advertising laws cannot control such precise “psychological operations”, and Facebook has always dressed itself up as a “technology platform”. Zuckerberg explained at the hearing that the platform algorithm is not responsible for content, but only helps people “connect”. But in fact, their algorithms determine who sees what and who does not see what. This is no longer a neutral intermediary, but a shaper of reality.

The power of the platform is greater than you think

Platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have greater influence than we think. The platform not only determines which content will become popular and whose speech can be spread, but also directly shapes our worldview through the recommendation mechanism.

So what can we do? From silent users to active citizens

1. Algorithm transparency: users have the right to know “why this is it”

We should promote a basic right: when you see a political content, you have the right to know how it appears in front of you. The platform should mark “recommendation basis” next to each political post or advertisement – for example: “You have recently paid attention to related topics”, “This content is recommended by ×× algorithm”, “Your area is the target of this advertisement”, etc.

2. Political advertisements must be transparent: This is not an “industry secret”, this is a citizen’s right

There is a set of strict legal regulations for political advertising in old-fashioned communication methods such as television, radio, and newspapers: public information such as the funding party, content source, and delivery time. Therefore, we need to promote three public obligations of digital advertising: 1. Who invested? (Who is the investor?) 2. Who is it invested for? (Which groups? Based on what characteristics?) 3. How to invest? (What algorithms and models are used?) Transparency is not about punishing the platform, but about ensuring that we can participate in politics based on the same reality.

In the end: Algorithms are not a scourge, but they must be regulated. Platforms should not be the opposite of democracy. If designed properly, they can become a new space for democratic discussion; but if there are no rules, they will become a tool for dividing society and manipulating cognition. What we want is not a perfect system, but a transparent, responsible system with space for public participation. In a democratic era, even if power is hidden in code, it must be responsible to humans.

reference

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Media (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429242595

Crawford, K., & JSTOR. (2021). The atlas of AI power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2020). Data and the Threat to Human Autonomy. In The Costs of Connection (pp. 153–184). Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503609754-007

Cadwalladr, C., & Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 17). Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Maalsen, S. (2023). Algorithmic epistemologies and methodologies: Algorithmic harm, algorithmic care and situated algorithmic knowledges. Progress in Human Geography, 47(2), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221149439

Be the first to comment