Imagine paying a premium price for a Tesla, only to find that it can’t get into your workplace car park, not because there’s no space, but because it’s seen as a security threat. This is exactly the situation faced by some Chinese Tesla owners — Teslas are banned from the car parks of some government agencies, institutions and state-owned enterprises.

Behind this incident is a growing global debate: How much data should smart vehicles actually collect? Who has the right to access this data? Tesla’s ban in China reveals key questions about privacy, surveillance and data sovereignty.

Why Are Teslas Being Banned?

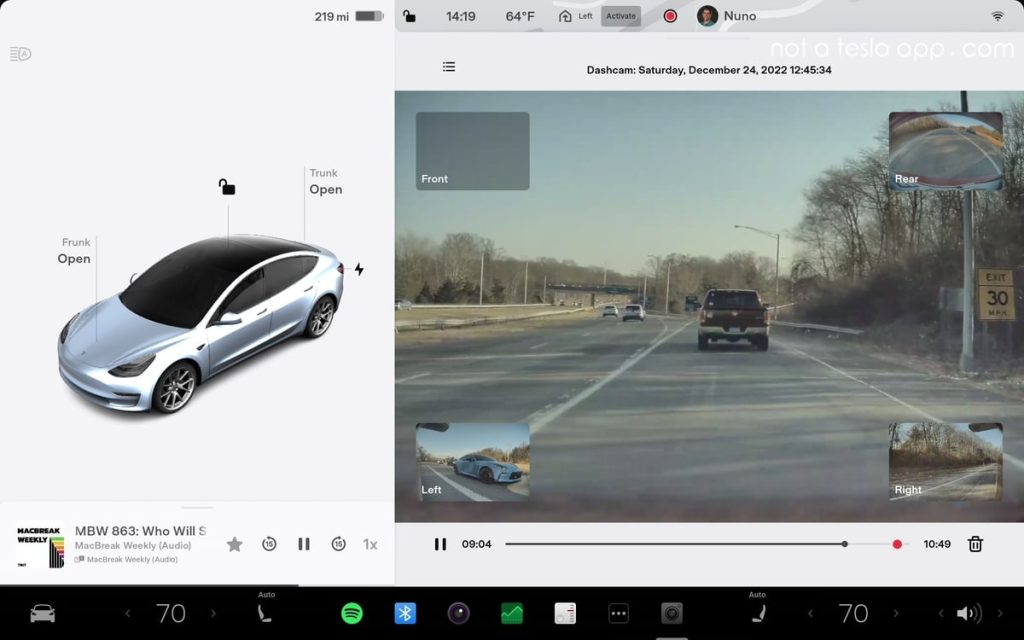

Why is Tesla so popular? In addition to the electric drive and cool appearance, it is more like a “thinking car” — equipped with high-definition cameras, a variety of sensors, as well as powerful data processing and storage systems. It is these high-tech features that make it at the forefront of smart driving. But on the other hand, it is these features that have also raised concerns about data security.

In China, government officials have noted the sensitivity of Tesla’s in-car cameras. While Tesla’s cameras don’t record all the time, they actively record footage of the environment around the vehicle in certain situations, such as when Sentry Mode is on or when using the Autopilot Assist feature. These features were initially intended to enhance security, such as prevention of burglary, obstacle avoidance and road recognition. But the problem is that they can also sometimes inadvertently record footage near government offices or military installations.

The issue sparked a public outcry in 2021. At the time, the Chinese military announced that it was banning Teslas from certain military housing areas for information security reasons. According to Reuters and other media reports, the documents stated that videos captured by Tesla’s external cameras could be uploaded to overseas servers without being screened, which in turn “risked leaking state secrets.” Subsequently, a number of government agencies and state-owned enterprises followed suit by taking restrictive measures to exclude Teslas from their car parks. This decision has left many car owners angry and confused, with some users asking on Weibo, “Who will be responsible for the loss of a car bought at a high price that is not even allowed to enter the unit?”

As Harris (2022) argues, even though there’s no evidence that Tesla gathers more data than what customers agree to in its terms of service, outsiders still don’t fully understand what kind of data Tesla cars collect or how that data is used. This raises the question—who really controls the data: the car owner or the company.

The Bigger Problem: Data, Privacy, and National Security

The banning of Tesla in China is not an isolated incident, what is behind it is actually a big question that the world is experiencing: as our lives become more and more digitised, who should really be in control of the data? You can see that different countries are responding to this challenge in their own ways. In the U.S., national security concerns have led the government to frequently restrict foreign tech platforms like Huawei and TikTok, preventing user data from being controlled by “outside forces”. Ironically, U.S.-based tech giants such as Meta and Google have also long been engaged in deep data mining without the knowledge of their users. For ordinary people, this “double standard” phenomenon has turned “data security” into a distant slogan. In contrast, Europe is more forward-looking in terms of digital rights. The introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) explicitly grants users a series of rights such as “knowledge, consent, access and deletion”, emphasising that users are the true owners of their personal data. This institutional design is an effort to balance the tension between technological efficiency and individual rights. China’s strategy is to place greater emphasis on “data sovereignty” — requiring companies (especially foreign companies) to keep data collected in China local and subject to their own laws. The logic behind these policies is based on national security concerns.

But here’s the thing: as governments impose more and more data controls for the sake of “collective security,” how much room is left for the privacy of ordinary people? While dealing with potential risks, do we have to accept more surveillance and restrictions? This is one of the biggest challenges of today’s era — how do we find a truly fair and reasonable balance between “protecting” and “being protected”?

Key Ethical Issues

The most powerful aspect of smart cars is no longer horsepower, but data capability. As Internet of Things (IoT) technologies become more embedded in the design of new vehicles, cars are now capable of collecting, processing, and transmitting vast amounts of information through interconnected hardware and software systems (Prevost & Kettani, 2020). As our data is increasingly collected, analysed and utilised, a fundamental ethical question surfaces: do we have the right to decide the fate of our data or not?

According to Suzo (2019), user interests tend to be protected only when they match business objectives. However, companies often prioritise minimising their own legal risks and expenses. As a result, global policy responses frequently lead to compromises that overlook or weaken individual user rights. For example, one of the most disturbing is the mechanism of “default consent”. When purchasing a car or activating a system, many users are often asked to accept, in one fell swoop, thousands of words of user agreements that hide complex authorisation clauses. Once you click “I agree”, you may be giving up control of your location, voice and other data. The problem is that most people simply don’t have the capacity or time to understand the legal implications.

This is not just an issue between users and businesses, but a moral challenge for society as a whole to face. We need to re-examine: is what technology can do equal to what it should do? In the absence of a transparent, controllable, user-centred data governance system, the so-called “intelligence” is likely to be nothing more than surveillance wrapped up in the name of convenience. And this is precisely the privacy ethical dilemma that we need to be most vigilant and reflective about in contemporary times.

Algorithms and Platform Power: Who’s “Driving” After Tesla Drives Away?

When discussing privacy, we often focus on whether or not data is being collected, but what’s really more important to care about is: what happens to that data after it’s collected? Who is in control of where it goes and what it is used for? In a smart car like Tesla, once uploaded, the user’s data doesn’t just “exist” on a server. It’s fed to algorithms for system optimisation, feature recommendations, and even risk assessment. The real problem is that all of this happens almost without the user’s knowledge. You don’t know if the system has labelled you an “aggressive user” or a “high-risk driver” based on your driving style, or if the platform has recommended features, adjusted service strategies, or even affected your access to certain insurance policies in the future because of these judgements. We also don’t know if these judgements will affect your access to certain insurance, financial services or technology updates in the future. The algorithmic logic behind these judgements is closed, unexplainable, and impossible to correct or reject.

In other words, even if you are the owner of the car, you are not necessarily the “decision maker”. The moment you get out of the car, another “invisible driving system” is already in operation. It’s not just the flow of data, it’s a set of algorithmic logic that continues to shape the relationship between you and the platform. What’s even more alarming is that this data-driven “automated judgement” will gradually permeate every detail of your interaction with your Tesla. For example, the system may decide to turn on certain features and turn off certain offers without you knowing why. This is a new kind of platform power: not by controlling the product, but by controlling the way users are “seen and defined”.

So the question we need to ask is not just “did Tesla collect the data”, but goes further: how was the data interpreted? Can the algorithm’s judgement be scrutinised? Do users have the opportunity to say “I disagree”? If there are no clear answers to these questions, then even if you are the owner of a car, you may just be a “modelled object” in the platform’s system. In the world of digital driving, you may no longer be in the driver’s seat.

How Can These Privacy Risks Be Addressed?

In the face of these privacy risks, we can’t just be anxious or accept them silently, but we should seriously think about a key question: is it possible for us to guard the control of our data or not? The answer is yes, but the road is not easy, and it requires the triple cooperation of system, technology and public awareness.

First of all, Governments need to consider how regulations imposed on tech companies will inevitably affect individual human rights when designing effective data governance frameworks (Suzor, 2019). Institutional development remains the most fundamental guarantee. Governments not only need to set norms to regulate the data collection and use behaviour of technology companies, but also need to realise from the outset that any data rule is not just a technical specification, but also a redistribution of citizens’ rights. Many countries are already trying to establish their own data governance frameworks, using clearer legal language to define what constitutes “legitimate data use” and what constitutes an infringement of personal privacy. However, the system is only a starting point, the key is to be able to truly implement, and let users know that “I have the right to say no”.

Secondly, businesses can no longer treat “user data” as a default resource. While technological advances are important, they should not come at the expense of privacy. What we’d like to see is a new way of thinking about design: data use must be more transparent, with user interfaces that make it clear what data is being captured, where it’s being used, and how easy it is to opt out. A truly responsible tech product should encourage users to make informed choices, rather than hiding complex settings in layers of menus that silently capture everything about you.

Last but not least, we ourselves cannot be absent from this dialogue on digital rights. Many of us may think, “I’m just an ordinary user, what can I do?” But the truth is, it’s every click of “agree” and every time we ignore a privacy policy that perpetuates this unequal data relationship. We can start by making changes ourselves — by understanding the privacy settings of our platforms, by paying attention to data rights issues, by voicing our concerns on social media. As more and more people start to ask questions, demand transparency, and refuse to acquiesce, the “voice of the user” will become an important force for change. Privacy is never a technical issue, but a social choice.

Conclusion: Technological Progress VS. Personal Privacy

We are living in an era of rapid technological advancement, where convenience and risk go hand in hand. Smart devices have improved efficiency but are also quietly eroding our data sovereignty. We should not reject technology out of fear, nor should we give up privacy in the pursuit of innovation. Ideally, the future should be transparent and controlled: we know how our data is being used, and have the right to choose and withdraw authorisation at any time. Now is a critical time to set boundaries for digital life, and to make technology serve people, not override them.

References

Aman. (2023, March 31). What is Tesla Sentry Mode? Everything you need to know! Tesla Stir. https://www.teslastir.com/what-is-tesla-sentry-mode-everything-you-need-to-know/

Harris, M. (2022). The radical scope of Tesla’s data hoard: Every Tesla is providing reams of sensitive data about its driver’s life. IEEE Spectrum, 59(10). https://doi.org/10.1109/MSPEC.2022.9915627

Prevost, S., & Kettani, H. (2020, January). On data privacy in modern personal vehicles. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Big Data and Internet of Things (BDIoT ’19) (Article 2, pp. 1–4). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372938.3372940

Reuters. (2021, May 21). Tesla cars barred from some China government compounds: sources. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/tesla-cars-barred-some-china-government-compounds-sources-2021-05-21/

Upstream Auto. (n.d.). GDPR. https://upstream.auto/blog/gdpr/

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Be the first to comment