In the contemporary world, artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping almost every sector of society, including healthcare, media, teleportation and education. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation in different aspects of society, including governance, offers both a great opportunity and complex challenges. Consequently, this gives rise to the need for algorithmic governance to make sure algorithms embedded in AI technologies operate appropriately and stay away from prejudice, discrimination, and breaking the law or moral standards (Wang et al., 2024). This includes the use of AI systems to assist, or even automate, government decision-making from policy formulation to service delivery. It is worth noting that the use of AI in governance and businesses often depends on the collection of large quantities of personal data for processing, which introduces a host of privacy concerns and the risk of misuse or illegal access. Further, AI tools can also be used for surveillance in different contexts, which raises concerns regarding individual autonomy and trust. This paper builds on the contested idea about AI by Kate Crawford that “AI is neither artificial nor intelligent” in her book Atlas of AI, to propose the notion that the unchecked nature of AI in facial recognition technology poses a serious threat to public anonymity, civil liberties, and social equity.

Privacy and Surveillance

AI-empowered mass surveillance can limit freedom of expression and association with chilling effects. Governments and corporations all over the world are adopting facial recognition technology as a central way of controlling public space. Sold as a tool for safety and convenience—catching criminals, streamlining airport queues, unlocking phones. However, behind that glossy pitch is a creeping erosion of a simple right most of us have taken for granted: the ability to walk and run anonymously in the streets (Ergashev, 2023). Anonymity is everyone’s right to make their way through life without being tracked. That’s what facilitates the right to protest without the fear of retribution, the right to shop without being profiled, and to be in public space as a human without being made an information point. The greatest concern in current times is the threat facial recognition – enabled by AI and automated surveillance systems- poses a threat to these liberties (Mirishli, 2025). Today, cameras installed in public spaces are linked to databases capable of identifying and tracking people in real-time. It’s allowing your face and your identity to become a permanent ID card, and you might not even know it. To make matters worse, these aren’t humans watching you; they are algorithms.

Figure 1: AI-Based School Surveillance

Source: https://www.campussafetymagazine.com/news/ai-based-school-surveillance/80010/

Without human oversight, AI software scans millions of faces, matches them to databases, and triggers alerts. This kind of algorithmic governance means that decisions about who gets flagged, followed, or targeted are made by machines. This technology, by doing so quietly turns our everyday presence in public into data for the surveillance and control of the public, and with little accountability and disproportionate harm to marginalized communities, risks dragging democratic societies into a culture of permanent monitoring (Mosa et al., 2024). The history of facial recognition systems of bias–misidentifying people of colour, women, and non-binary people–is well documented. You’re statistically more likely to be falsely flagged if you’re Black or brown (Skynews, 2019). A report by Skynews indicates that based on an independent report, of all ‘suspects’ flagged by Met’s police facial recognition technology 81% are innocent. This goes to show that this tech does not remedy inequality but rather automates it in a society where policing and surveillance disproportionately impact marginalized groups.

Winners and Losers

In order to understand who the winners and the losers are during this rise of facial recognition and the decline of public anonymity, it is crucial to understand what the driving force behind the use of facial recognition is. While there are numerous entities pushing for the use of widespread facial recognition, more often than not, the major players are governments, law enforcement agencies, and tech companies (Mirishli, 2025). These major players are, in turn, driven by the singular focus of leveraging the capabilities of facial recognition to pursue their own agendas. It is the governments wanting control, tech firms wanting profits and security firms trying to sell you fear-based solutions. Ordinary citizens, however — particularly those in danger of becoming the focus of over-surveillance — are missing from this discussion (Hynes, 2021). There is rarely public consultation or informed consent, and these systems will be running most of the time. Most people don’t even know they exist, let alone how your data is stored, shared, or used. This lack of transparency is not a coincidence. This is part of a broader pattern of algorithmic governance, where complex decisions are made in secret, in the name of safety, and rarely accessible to scrutiny (Just & Latzer, 2016).

Ordinary citizens are on the losing side because in the event an AI system makes an error or does harm, determining who is responsible can be complex. Is it the data scientists who trained the model, the engineers who deployed it, the policymakers who gave the okay to use it, or the algorithm itself? This is because AI development and deployment can be distributed across different parties, which can compromise the responsibility and accountability of each one (Hynes, 2021). This exhibits one of the challenges of algorithmic governance underscored by the legitimacy of algorithmic governance being undermined. The lack of clarity about accountability often results in a diffusion of responsibility, impairing the ability to learn from mistakes and to come forward with redress to those affected or hindering future occurrences (Mirishli, 2025). That’s not all, loss here can also occur in the form of privacy violations that can result in identity theft, discrimination, damage to reputation, and undermining of trust in the government and in technology.

The Global Context—and a Warning from History

While facial recognition might feel futuristic, there are traces of it in older systems of surveillance and control. Historically, surveillance has never been neutral—it has always reflected the priorities and power structures of the ones who are controlling it. The act of ‘watching’ has never been about just watching but rather about deciding who counts, who’s suspicious, and who calls the shots (Ergashev, 2023). Evidence of this traces to as early as colonial censuses or as contemporary as population registries or Cold War intelligence. The difference in the current age of surveillance is the scale, speed, and seamlessness with which surveillance works, including automation, artificial intelligence, and growing data ecosystems. Beyond just recording your presence, facial recognition identifies, assigns, and traces you in real-time, usually without your knowledge or consent. Once your face is turned into a data point, it is almost impossible to opt-out.

China is a classic example of the popularity of facial recognition technology, so much so that it has become embedded in the state’s governance. There are millions of cameras with AI software in place watching streets, train stations, schools and places of worship. The Social Credit System routinely scores citizens based on their behaviour, leading to outcomes such as travel bans, restricted public services, and other serious consequences (Hussein, 2022). This speaks to the unrestricted circumstances whereby deep learning technology has become increasingly popular following the high resilience to the many alterations that can change the recognition process offered by AI. What’s more striking isn’t so much the technology but how technology has been seamlessly integrated into everyday life — depicted as a tool for order, trust, and modernity. When every step, every face, and every gesture can be traced, dissent is risky. As digital systems govern and, where appropriate, enforce behaviour, this model of algorithmic governance renders public space a controlled zone. As the Western democracies have not yet (massively) adopted such systems, the underlying architecture is being quietly built — with little scrutiny and no public debate at visible levels.

Figure 2: A Chinese national flag flutters near surveillance cameras mounted on a lamp post in Beijing

Source: HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/08/16/data-leviathan-chinas-burgeoning-surveillance-state

The point here is not that technology is not innately dangerous but rather that history suggests there is a need for awareness about technology’s guise of progress under surveillance. Surveillance tools have always been justified in every era as a necessary instrument of public order. But they often ended up repeating past inequalities and cementing power in the hands of a few (Adjabi et al., 2020). AI can automate tasks and provide useful ideas, but we must still employ human judgment and intervention, particularly in regard to decisions that have heavy consequences on people or society. Fully autonomous systems can lead to error, unintended harm and the lack of flexibility under unforeseen circumstances.

Case studies and current situation analysis

A clear understanding can be gained from examining the case studies of Clearview AI, and PimEyes AI companies. Clearview AI, and PimEyes demonstrate the very real consequences that can result when our faces become searchable, scannable and exposed to everyone with the right tools, from a government to a corporation to a perusing stranger.

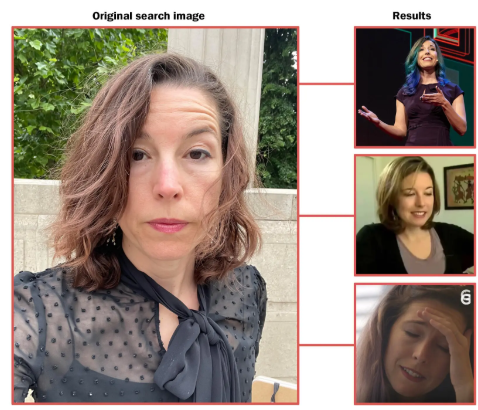

Clearview AI: Surveillance Capitalism Meets Law Enforcement

The business model of photo surveillance startup Clearview AI involved scraping over 20 billion images on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and even news platforms, all without consent. They were then fed into a facial recognition engine that has been marketed to law enforcement agencies around the world — including in the U.S., Canada and parts of Europe. Essentially, the company built a private surveillance tool with the ability to identify almost anyone, anywhere. With a blurry photo from a CCTV feed, police could upload it to a vast, unregulated database of faces, including yours or mine, and get back potential matches without us ever knowing we were part of it.

Figure 3: Scraping the Web Is a Powerful Tool.

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/clearview-ai-scraping-web/

This case presents several critical concerns, including consent and autonomy, where the faces of individuals became public property after being harvested, indexed, and weaponized without their concern in the name of public safety. There is also the issue of algorithmic governance where law enforcement agencies bypass traditional legal process like warrants or oversight by handing over identification power to algorithms. The lack of accountability reflects in some cases to wrongful arrests caused by misidentification, evidencing how automated systems can err. That’s not all, power asymmetry also manifests here since there’s nothing anyone can do to opt out, delete their data, or contest a false match. Concomitantly corporations are making profits and states strengthen their ability to do invisible surveillance.

PimEyes: Facial Recognition for the Masses

Figure 4: The original photo used to do an image search on PimEyes, left, and just a few of its results for the author, Kashmir Hill.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/26/technology/pimeyes-facial-recognition-search.html

While Clearview works in the shadows of law enforcement, PimEyes puts facial recognition in the palms of everyone’s hands who lives on the internet. This Poland based company lets you upload a photo, then searches every blog, website or image board to tell you where else that face has been seen. At first glance, it might seem empowering, like a tool for tracking your digital footprint, but the implications are chilling. For one, something as simple as standing at a protest or a bar no longer means you are anonymous from strangers who can snap your photo and find your identity online. The barrier between the physical and digital-self collapses. Further, the company says it only links to publicly available images, but it does not ask for consent. It also offers no context of where or why these images were posted. This surveillance without government oversight or corporate restraint exhibits the capacity for private individuals to turn facial recognition into weapons against other people, sometimes for malicious, hurtful or predatory purposes (as in, stalking, doxxing or harassment) (Kiene, 2024). Facial recognition is no longer the province of governments: PimEyes serves as a reminder of how it is becoming democratized, producing a world where anyone can spy on anyone else.

Conclusion

Today, the combination of facial recognition with automation and with algorithmic governance risks taking the pattern in a new direction. Without public debate, basic legal safeguards and robust mechanisms of accountability, we run the risk of normalizing a world in which our faces can become passcodes, our movements can be data and our freedoms can be negotiated.

References

Adjabi, I., Ouahabi, A., Benzaoui, A., & Taleb-Ahmed, A. (2020). Past, present, and future of face recognition: A review. Electronics, 9(8), 1188. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/9/8/1188/pdf

Ergashev, A. (2023). Privacy concerns and data protection in an era of ai surveillance technologies. International Journal of Law and Criminology, 3(08), 71-76. https://inlibrary.uz/index.php/ijlc/article/download/38845/39389

Hussein, S. N. (2022). Win-Win or Win Lose? An Examination of China’s Supply of Mass Surveillance Technologies in Exchange for African’s Facial IDs. Pretoria Student L. Rev., 16, 73. https://upjournals.up.ac.za/index.php/pslr/article/download/4506/3890

Hynes, M. (2021). Digital Democracy: The Winners and Losers. In The Social, Cultural and Environmental Costs of Hyper-Connectivity: Sleeping Through the Revolution (pp. 137-153). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/978-1-83909-976-220211009/full/pdf

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kiene, K. (2024). Open-Source Surveillance-Do You Own Your Face?. https://knowledge.uchicago.edu/record/11992/files/Open-Source%20Surveillance-%20Do%20You%20Own%20Your%20Face_-%20Kiene.pdf

Mirishli, S. (2025). Ethical implications of AI in data collection: Balancing innovation with privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.14539. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2503.14539

Mosa, M. J., Barhoom, A. M., Alhabbash, M. I., Harara, F. E., Abu-Nasser, B. S., & Abu-Naser, S. S. (2024). AI and Ethics in Surveillance: Balancing Security and Privacy in a Digital World. https://philarchive.org/archive/MOSAAE-2

Skynews. (2019, July 3). 81% of “suspects” flagged by Met’s police facial recognition technology innocent, independent report says. Sky News; Sky. https://news.sky.com/story/met-polices-facial-recognition-tech-has-81-error-rate-independent-report-says-11755941

Wang, X., Wu, Y. C., Zhou, M., & Fu, H. (2024). Beyond surveillance: privacy, ethics, and regulations in face recognition technology. Frontiers in big data, 7, 1337465. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/big-data/articles/10.3389/fdata.2024.1337465/pdf

Be the first to comment