AI is getting better at ‘understanding’ you, but is it really helping you?

Have you ever noticed that when you just casually mentioned “fried chicken” to a friend, social media, food delivery apps, and even video sites all started to frantically recommend fried chicken ads to you? You might think – “Oh my god, is AI eavesdropping on me?” In fact, it’s not just eavesdropping, but the algorithm is doing a super predictive analysis of your data.

How does it know you want to eat fried chicken?

The recommendation systems of social media, search engines, and e-commerce platforms are all based on AI and big data analysis. They “predict” your needs in the following ways:

- Keyword & context analysis: You may enter the word “fried chicken” in a chat software, social media, or even a search engine, and AI will recognize this keyword and push relevant ads.

- Browsing behavior: Even if you don’t enter “fried chicken”, if you have recently followed videos or articles related to fried chicken, or stayed on a fried chicken advertisement for more than a few seconds, AI will “judge” that you are interested in fried chicken.

- Location data: If you are near a certain food business district, the food delivery software may actively push discount information about nearby fried chicken stores to you because the algorithm thinks “you may be hungry.”

- Social relationship influence: Has your friend been browsing fried chicken-related content recently? AI may infer that you have similar interests and push similar recommendations to you.

“Convenience” vs. “Manipulation” of AI recommendations

The original intention of these algorithms is to help you find what you need faster. For example, when you want to eat fried chicken, you can place an order with one click, and the fried chicken will be delivered to you in a few minutes. It’s awesome! But at the same time, they are also guiding your choices, and even make you feel that “Is it me who wants to eat fried chicken, or is it AI that makes me want to eat fried chicken?” What’s more frightening is that algorithms may strengthen your consumption habits. For example: you ordered fried chicken once, and the food delivery software started to push more fried chicken shops, and you may not be able to resist ordering it again next time. You browsed a product once, and the shopping website will continue to recommend similar products to you, and you may end up buying a lot of things you didn’t intend to buy. You browsed some negative news, and the social platform may continue to push similar content, causing your mood to be affected.

How do algorithms “shape” your world?

Although these recommendation algorithms can make our lives more convenient, their real purpose is to make users stay longer and consume more, rather than to make you make the most rational decision. Noble (2018) found that Google’s search results will give priority to displaying content that is beneficial to itself, while users’ privacy, personal information and even their “immaterial labor” are used by algorithms for profit. We should learn to distinguish the boundaries between “convenience” and “manipulation” recommended by AI. Algorithms not only affect your consumption decisions, but also shape your cognition, behavior and social order. Just & Latzer (2016) believe that algorithms not only determine what you see online, but also influence how you think and how you make decisions.

You think you are choosing fried chicken? In fact, the algorithm is choosing you!

The behavior of each user may seem trivial, but when thousands of people make similar choices, the “ecology” of the entire Internet will change accordingly. For example, when many users search for a topic, the algorithm will identify it as a hot topic and push it to more people, which will affect news issues, public opinion, and even business decisions. This means that we are not only passive recipients of information but are actually “training” algorithms to continuously strengthen our interests while filtering out information from other perspectives.

This impact goes far beyond social media. On e-commerce platforms, the recommendation system will push products based on the user’s browsing history, giving people the illusion that “this is exactly what I need”; on news platforms, the algorithm prioritizes content similar to the user’s views, causing people to gradually fall into the information cocoon and even further solidify the world view. The reason why AI can accurately predict personal preferences is because it analyzes based on large-scale user data. For example, if you frequently follow fried chicken-related content, the system will automatically push similar advertisements and optimize the push strategy based on your browsing history, likes and comments to make recommendations more accurate.

From a deeper perspective, algorithms not only affect individual decision-making, but also reshape social order. Information screening and recommendation mechanisms will guide group behavior and strengthen specific social norms. Algorithms are not just neutral tools, but an invisible force that shapes social interactions. When an algorithm dominates the information flow, it not only affects individual choices, but also reconstructs social structures. For example, when certain views are constantly strengthened and different voices are blocked intentionally or unintentionally, the diversity of social discussion will gradually be lost, which will in turn affect public decision-making and social order (Hechter & Horne, 2003).

Social Media: An Algorithm-driven Information World

Among all areas affected by AI algorithms, social media is undoubtedly the most obvious (Napoli, 2014). Algorithms not only change the way we obtain information, but also reshape the social and cultural, political ecology, and even influence the democratic process. As Suzor (2019) pointed out, Internet platforms are not just commercial companies, they actually affect the entire social structure by managing information exchange between users. During the 2016 U.S. election, Facebook’s personalized push mechanism has been criticized for pushing political ads and targeted messages. Based on user likes, browsing history and other data, the platform recommends political content that meets its existing interests and positions. This mechanism is very likely to lead to the Echo Chamber Effect, that is, users only have access to information that conforms to their own position, further aggravating political division and social confrontation.

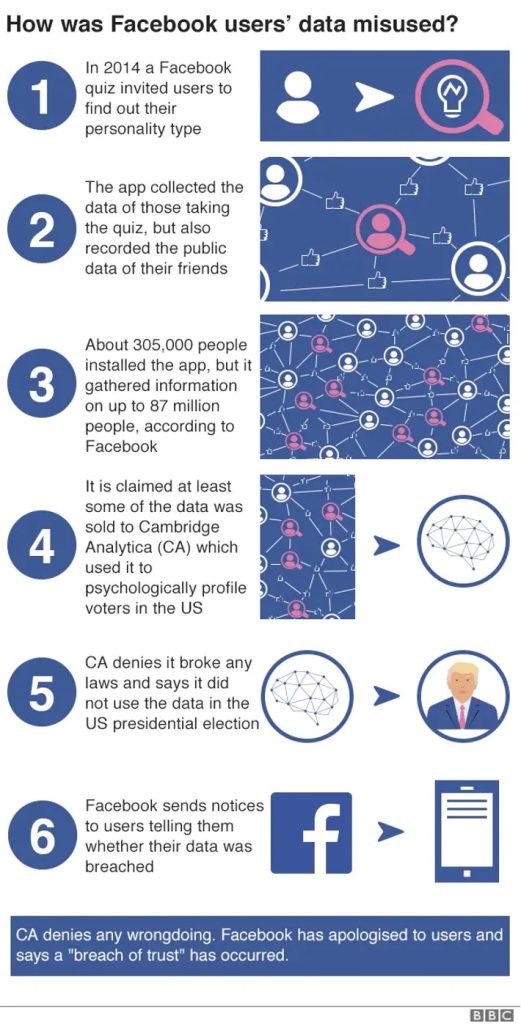

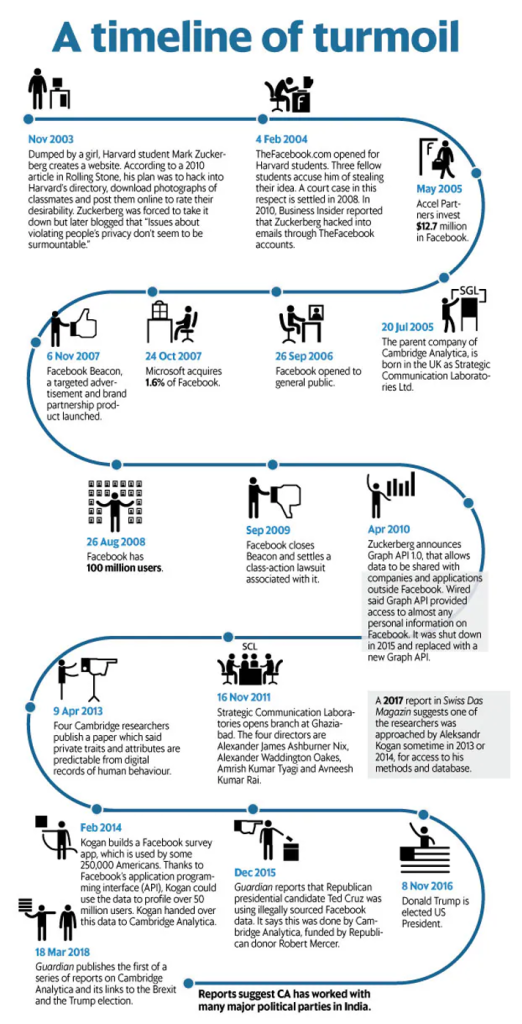

What’s more serious is that some political advertisements and news on Facebook have not undergone strict fact verification and are even misleading or false information. In 2018, the Cambridge Analytica data breach scandal was exposed. The company used Facebook vulnerabilities to illegally obtain about 87 million user data and used this data to accurately place political advertisements to help the Trump team influence voter decisions. Although Facebook denies direct involvement in the manipulation of the election, the incident has sparked strong public doubts about its data management and algorithm transparency. Faced with huge public pressure, Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged the problem many times at a congressional hearing and promised to strengthen data protection and content supervision, how to regulate social media platforms remains a fierce controversy worldwide, with governments and relevant agencies beginning to revisit how to restrain tech giants to ensure they do not harm the public interest (Isaac, 2016). Scholars point out that society is gradually moving towards “platformization” and forming a “platform society” (Helmond, 2015; van Dijck et al., 2018). Among the many platform services, social media is particularly popular. At present, at least 2.7 billion people in the world use Facebook’s applications (including Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger), among which Facebook’s daily active users alone have reached 1.84 billion (Facebook Investor Relations, 2021). Although social media platforms have brought convenience, they have also been strongly criticized for a series of social and economic problems.

As Hongladarom (2020) said, we are entering the era of “surveillance capitalism”, where personal data is collected on a large scale to predict and manipulate consumer behavior. “In addition, the powerful influence of Internet platforms has raised concerns (Helberger, 2020). They not only control the way society communicates but may also manipulate user attention and shape reality through technical means. Critics believe that social media is exacerbating social divisions and political polarization and facilitating the spread of hate speech and false information, thereby damaging public discourse space and democratic systems (Persily & Tucker, 2020). At the economic level, social media platforms have made industries such as retail and publishing increasingly dependent on platform intermediaries. At the same time, they have also been accused of evading taxes and abusing their market dominance and have even triggered antitrust investigations and lawsuits in Europe and the United States (US House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law, 2020).

Algorithm Choice: The Invisible Power Shaping the Internet and User Behavior

Algorithms are the core force that affects the operation of the Internet and user behavior. With the popularity of the Internet, every click, browse, search, and even stay time we will be recorded and learned and analyzed by algorithms. These tiny behaviors continue to accumulate, not only affecting the experience of individual users, but also shaping the information flow and dissemination model at a larger level. Different algorithms make decisions based on this data, deciding which information is recommended, which content is hidden, and may even change the user’s views and behavior.

Algorithms not only affect individual experience, but also shape the development direction of the Internet. It determines what content will be promoted, influences creators’ decisions, and drives specific goods, services, or information into the market. Every interaction between users may trigger unexpected trends at the macro level, thereby changing the network ecology. Therefore, the operation of algorithms not only meets personal needs, but also deeply affects the structure and interaction methods of the entire network.

More importantly, the algorithm screening and recommendation mechanism determines the information we are exposed to, and thus shapes our worldview. It affects our consumer decisions, social interactions, and may even strengthen our beliefs and stances. By constantly “recommending” or “hiding” information, algorithms invisibly shape our cognition. Its impact has far exceeded the technical level and has become an important part of modern network governance.

The double-edged sword of Artificial Intelligence: progress and ethical dilemmas

The rapid development of AI has brought many opportunities, from improving medical diagnosis to optimizing social interactions to improving labor efficiency. However, this technological change is also accompanied by profound ethical challenges, such as algorithmic bias, environmental impact, and threats to human rights. These risks often exacerbate existing inequalities and make marginalized groups more vulnerable (UNESCO).

The impact of AI is not limited to personal privacy leaks, changes in the news ecology, and data abuse, but also involves broader public interests. When technology is dominated by large companies, its application often revolves around commercial interests, such as precision marketing and advertising push, which in turn shapes public expectations of AI. Some people believe that AI is more reliable than humans and can make optimal decisions in key areas such as health, education, and justice. However, Crawford (2021) pointed out that if we only focus on the algorithm itself and ignore its social and environmental impact, we may pay a heavy price. Technological progress is important, but if we ignore its energy consumption, environmental costs, and social costs, we may end up losing more than we gain.

Conclusion: Beware of the invisible manipulation of algorithms

From fried chicken advertising to political elections, from shopping recommendations to news push, AI algorithms are quietly shaping our world, affecting consumption habits, information acquisition, and even political stance. Although they provide convenience, they are not neutral, but are deeply driven by commercial interests. As users, we cannot completely get rid of the influence of algorithms, but we can stay alert and make choices actively instead of being passively manipulated. First, understanding how the algorithm works is key. Adjusting privacy settings can reduce intervention in personalized recommendations; broadening information sources can avoid falling into the information cocoon; in the face of every “precision push”, we should maintain doubt rather than blind trust. At the same time, it is also crucial to learn how to manage a platform. The platform not only affects our communication methods, but also has a profound impact on public culture and users’ social and political life (Suzor, 2019). Facebook’s impact on democracy illustrates the gap between social values and legal regulation. From “fried chicken recommendation” to “political manipulation“, the impact of AI algorithms is far beyond our imagination. Maybe next time, when you see a “just needed” push on social media, you might as well ask yourself – is this what I really want? Or is the algorithm quietly “feeding” my decision?

Reference

Crawford, K. (2021). Introduction. In Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence (pp. 1-22). New Haven: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300252392-001

Facebook Investor Relations. (2021). Facebook reports fourth quarter and full year 2020 results. https://investor.atmeta.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2021/Facebook-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2020-Results/default.aspx

Hechter M, Horne C (eds) (2003) Theories of Social Order. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Helberger, N. (2020). The political power of platforms: How current attempts to regulate misinformation amplify opinion power. Digital Journalism, 8(6), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888

Helmond, A. (2015). The platformization of the web: Making web data platform ready. Social Media + Soci‐ ety, 1(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080

Hongladarom, S. (2020). Shoshana Zuboff, the age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the New Frontier of Power. AI & SOCIETY, 38(6), 2359–2361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01100-0

Isaac, M. (2016, November 12). Facebook, in cross hairs after election, is said to question its influence. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/14/technology/facebook-is-said-to-question-its-influence-in-election.html

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Napoli PM (2014) Automated media: an institutional theory perspective on algorithmic media production and consumption. Communication Theory 24(3): 340–360. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/comt.12039

Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York, USA: New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479833641.001.0001

Persily, N., & Tucker, J. A. (Eds.). (2020). Social media and democracy. The state of the field, prospects for reform. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

UNESCO.org. (n.d.). Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics

US House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law. (2020). Investigation of competition in digital markets. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-117HPRT47832/pdf/CPRT-117HPRT47832.pdf

van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190889760.001.0001

Be the first to comment