Imagine waking up to find that your most intimate conversations, secret fears, and private dreams have become commodities, quietly sold behind your back to the highest bidder. Or imagine applying for your dream job, only to find that you’ve been automatically rejected – not because you’re unqualified, but because an unseen digital gatekeeper unfairly judges you based on hidden biases. Algorithms silently orchestrate your online life and, increasingly, your offline life, wielding enormous power with minimal accountability.

While we often talk about artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithms as technological tools, the truth is much messier: these systems reflect us – and if left unchecked, they often reflect our worst instincts. From discrimination and surveillance to repression and exclusion, AI does not invent new problems; It magnifies old problems we haven’t solved yet.

Invisible Puppeteers: Algorithms and Your Digital rights

Algorithms are not just harmless lines of computer code; They are the invisible gatekeepers who decide what you see, who sees you, and how you experience the digital world. Originally designed to simplify choice and enhance the user experience, their opaque and unaccountable nature now poses a serious risk to our privacy and digital rights (Flew, 2021). As he puts it, algorithmic systems now constitute an “infrastructural force” – invisible but vital in shaping everyday life (Flew, 2021).

TikTok, Elections, and Algorithmic Radicalization

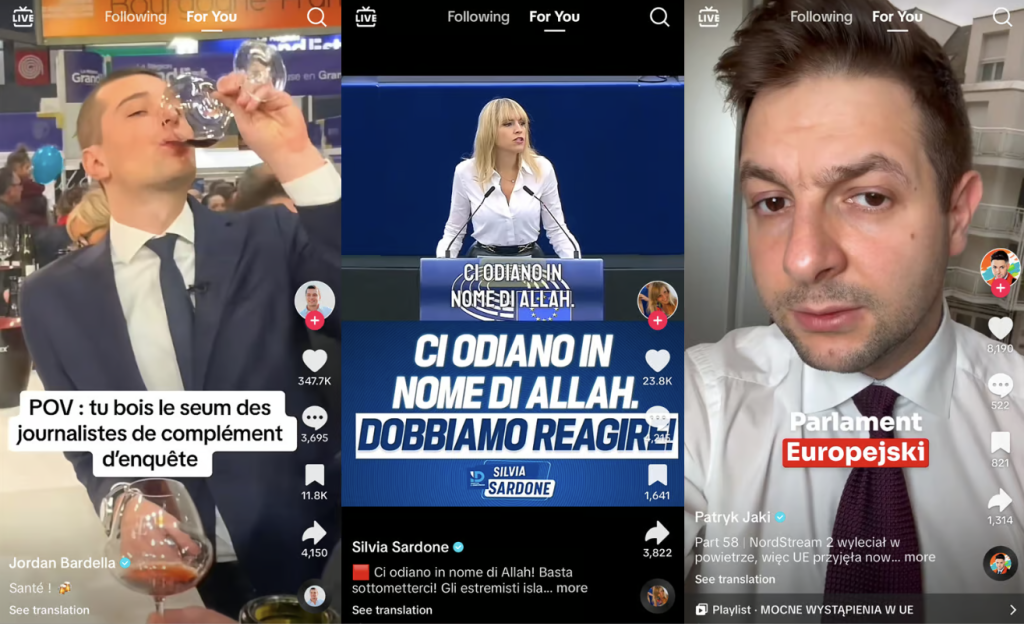

In May 2024, on the brink of European Parliament elections, TikTok’s algorithm was severely criticized following a study by researchers that uncovered evidence of it actively promoting far-right content amongst youths. According to a June 2024 report by Politico, far-right parties across Europe—most notably France’s National Rally and Germany’s AfD—used TikTok’s algorithmic design to rapidly gain traction among young voters. Experts noted that anti-immigration and nationalist messages were among the most widely promoted content, raising concerns that TikTok’s engagement-focused algorithm is fueling political radicalization among users aged 18 to 24.

More worryingly, this algorithmic push correlates with political outcomes – the youth support base of France’s far-right National Rally doubled during the campaign. TikTok claims it is simply “responding to user interest,” but the whistleblower revealed that the platform’s back end has been tweaked to prioritize engagement over neutrality, even if that means fostering divisive and dangerous material.

This case highlights how algorithms not only reflect preferences, but actively shape them. If left unregulated, they may hide behind a veneer of neutrality and push society toward extremism (Crawford, 2021).

Surveillance Capitalism: Turning Our Lives Into Data Goldmine

Behind this lies a deeper problem: surveillance capitalism. The term may sound technical, but that’s what it means. Platforms like TikTok, Meta, and Google make money not by selling you goods directly, but by collecting everything about you (your clicks, likes, even the time you spend looking at photos) and selling that data to advertisers who want to influence your behavior.

Imagine someone silently following you every day, observing what you read, buy, and even feel, and then selling that information to people who want to manipulate your choices. That’s basically what these companies are doing – at scale. They use algorithms to do this automatically, invisibly, and continuously.

Algorithmic Bias and the Reinvention of Inequality

In November 2024, Reuters published a report warning that business leaders were “sleepwalking into AI abuse.” The report highlights how companies are adopting AI tools in recruitment, risk assessment and even performance management without proper ethical oversight. One example is revisiting the Amazon case where their AI-powered recruitment tool showed a bias against women. Although Amazon pulled the tool in 2018, experts believe that similar systems are still widely used across a wide range of industries, and often with little transparency.

As Eubanks (2018) argues, these systems don’t just make decisions—they operationalize inequality, automating the same judgments that have historically punished the poor and marginalized (Eubanks, 2018). Algorithms trained on discriminatory data will perpetuate structural injustices unless they are consciously reorganized with fairness in mind. This is where the subject of this blog hits hardest: When algorithms are unregulated, they don’t just reflect the world – they reflect the world’s worst biases and encode them as objective logic.

AI systems trained on biased historical data can replicate and even amplify discrimination, while decision-makers assume objectivity. Without mandatory audit, disclosure, or diversity oversight, these tools can quietly influence hiring decisions, credit scores, and workplace dynamics in harmful ways (Just & Latzer, 2019).

Who’s Being Left Out of the Conversation?

Who is left out of the conversation? Even worse, the people most harmed by these technologies – women, children, people of color – often have the least say in how these technologies are designed and regulated. Consider TikTok: Young users are inundated with publicity, but are young voices involved in the design of the platform’s protections? In AI recruitment systems, do marginalized job seekers have a say in how these tools are evaluated? Very few.

As Andrejevic (2019) argues, automation tends to hide inequality behind neutral screens. If different voices are not included, then the digital system reflects the same inequities we’ve been trying to get rid of in the real world.

Exploiting Workers at Scale: When Algorithms Become Bosses

One of the most memorable examples of algorithmic power in 2024 is not happening in cyberspace, but on the floor of a warehouse. In August, Amazon’s AI monitoring system called “Time Off Task” was exposed, which automatically tracks employee productivity and issues dismissal notices without supervision. If employees pause for too long (for example, to use the bathroom or catch their breath), the algorithm flags them as underperforming. Pausing for as little as six minutes can trigger an automatic warning or even termination.

In many Amazon warehouses, workers began wearing adult diapers to avoid being labeled “idle.” The success rate of appeals against algorithmic dismissals is only 3 percent because the system rarely involves human reviews. In response, British trade unions sued Amazon for what they called the “dehumanizing management of machines,” and the European Union began drafting legislation to ban fully automated dismissals by 2025.

This is perhaps the clearest example of how algorithms can strip away basic dignity in the pursuit of productivity. They’re not just shaping opinions – they’re reshaping labor, rights, and what it means to be human in the digital economy.

Are Governments Doing Enough? A Look at Regulation

It is worth saying that some governments are trying. The European Union introduced the Digital Services Act (DSA) in early 2025. The law forces big tech companies to explain how their algorithms work, make their systems more transparent and give users more control over their data. Australia has also passed stricter privacy laws for tech companies.

Terry Flew noted that DSA represents a shift from passive enforcement to systematic accountability. It requires platforms not only to remove illegal content, but also to assess algorithmic risks and document how the recommendation system works (Flew, 2021).

But these laws face big challenges. First, tech companies are global and the law is national – how do you get US companies to comply with EU law? Second, companies like Meta and TikTok are very powerful and can resist or delay compliance. Third, there is always a tension between regulating technology and protecting innovation and freedom of expression (Pasquale, 2015).

Deepening the Dilemma: Power, Secrecy, and the Governance Gap

Despite mounting evidence of harm, governance of algorithmic systems remains fragmented and often symbolic. While the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and Australia’s privacy reforms mark progress, they have struggled to keep up with rapid technological change and the borderless nature of platform power. As Flew (2021) puts it, platform regulation increasingly involves asymmetrical conflicts: national legislation, but platforms designed around rules. The tension is especially acute when algorithms are treated as trade secrets, shielded from public scrutiny under corporate confidentiality agreements.

Moreover, the current regulatory model rarely gives users the power to meaningfully challenge the harms of algorithms. Pasquale (2015) warns against “black-box societies” in which opaque institutions gain legitimacy by default – not because they are fair, but because they are unchallengeable. What’s missing is not just better rules, but structural changes that redistribute power across digital infrastructure.

Signs of Hope: Ethical Alternatives and Resistance

While these stories may feel bleak, it’s important to remember that resistance and reshaping are also happening. Platforms such as Mozilla are building transparency tools that allow users to review algorithm recommendations.

In Europe, projects like AlgorithmWatch are driving public scrutiny of platform logic. Meanwhile, labor activists are using algorithmic literacy to challenge corporate practices and propose ethical alternatives, such as “human-machine collaborative” systems that combine automation with human judgment.

These grassroots movements show that if we organize, legislate, and innovate from the bottom up, the future is not entirely out of our hands.

So what can we actually do?

Practical Steps for Change

Solving these problems will require more than passing laws. We need a new way of thinking about how algorithms are built and used. Here are some practical ideas:

- Transparency: Companies should explain in plain language how their algorithms make decisions.

- Accountability: Users should be able to appeal or challenge algorithmic decisions that affect their lives.

- Inclusion: People from diverse backgrounds (especially those most affected) must be involved in designing digital tools.

Your Role as a Digital Citizen

As the role of a digital citizen,this may sound grand and abstract, but you are not powerless. Every time you use the Platform, click “accept” on a cookie, or share personal information, you are participating in the system. By staying informed, asking questions, and supporting groups pushing for better regulation, you’re helping to shift the balance.

Talk to friends. Educate your family. Support politicians and policies that prioritize digital rights. The more we demand fairness, the harder it will be for the tech giants to ignore us.

Where do we go from here? A new vision for algorithmic governance

If we want algorithms to serve the public good, governance must move beyond passive regulation. A proactive framework will combine legal oversight, ethical design and participatory accountability. For example, a public registry of algorithms co-managed by civil society could demystify decision-making logic. The “man in the loop” system must be the default, not the exception, especially in sectors such as hiring, law enforcement, and health care.

As Andrejevic (2019) points out, digital infrastructure not only provides services, but also reshapes the relationship between institutions and individuals. To regain agency, we must embed fairness, diversity, and transparency in the architecture of algorithmic decision-making. This is not just a technical fix; This is a political project.

Algorithms learn from us – let us teach them better

The algorithm will continue to exist. They help organize information, recommend movies, and even drive cars. But if we want them to make our lives better, not just make tech companies more profitable, we have to get involved. We must insist on systems that respect our privacy, treat us fairly, and reflect the diversity of the world in which we live.

If we don’t control algorithms, they will continue to reflect and amplify the worst parts of us. But with the right choices, they can also be tools for justice, inclusion, and equity. The future of AI is not a foregone conclusion. It’s being coded now – and we should all have a say.

References List

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Culture. In Automated Media (pp. 44–72). Routledge.

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1ghv45t

Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms (pp. 79–86). Polity Press.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Pasquale, F. (2015). The need to know. In The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms that Control Money and Information (pp. 1-18). Harvard University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0hch

Politico. (2024, June). TikTok helped the far right build a base ahead of the European elections. https://www.politico.eu/article/tiktok-far-right-european-parliament-politics-europe/

Be the first to comment