The data battle behind the TikTok ban

“A law banning TikTok has been enacted in the U.S. Unfortunately, that means you can’t use TikTok for now.” (Hamilton, 2025)

This is the official notice that American users saw on the TikTok app on the evening of 18 January 2025, which means that the ban on TikTok has officially been implemented in the U.S. Although the TikTok ban was signed by President Biden in 2024, 170 million American users were still in a state of great anxiety after the news was announced. Some angry young Americans have expressed their strong dissatisfaction with this, describing themselves as ‘TikTok refugees’ and switching to another Chinese social media platform, RedNote.

US officials have emphasised many times that TikTok is inseparable from the Chinese government, and warning that it is used to collect personal data of US citizens to threaten US political stability. This may seem like a national security and political battle between China and the U.S., but it also reveals that individuals have lost control over our personal privacy and data. Users often upload personal information, like comments and share videos with friends on TikTok, treating the platform as our own personal space (Suzor, 2019). However, do you really understand who collects and records such private data? And how will it be used?

It is important to note that the TikTok ban does not guarantee your data autonomy. Rather, it shows the neglected truth: we have become accustomed to surrendering our data autonomy to media platforms or regulators without knowing it. Therefore, we need to recognize that users should become the ultimate judges and beneficiaries of this data privacy struggle, and regain our data sovereignty.

The real issue behind the fight for data sovereignt

TikTok’s experience in the U.S. is not an isolated incident. In April 2025, TikTok faced over 500 million euros in fines after it was found to transmit European user data to China. However, some major US social media platforms have also been heavily fined for illegal use of user data, including Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Obviously, in the face of the increasing competition in the global digital platform, data privacy issues exist in most digital media (Flew, 2021).

However, there is still no social media platform that can truly protect personal data and ensure users can control our own data sovereignty. This is because platforms are reluctant to sacrifice the economic benefits that data brings or increase their governance risks (Nissenbaum, 2015). Ironically, the public relations strategies of most platforms involved in data scandals are very similar. The CEO would first apologize to the public and promise to conduct an investigation to find a solution for change (Flew, 2018). However, with the passage of time, the public will lose their memory, and the platform will not take any further action.

According to Nissenbaum (2015), the risks to data and privacy do not stem from a single company or country, but rather the entire digital media industry should be examined and more regulated governance measures provided. This is because the large technology companies have more power over the use of data due to the large amount of data they hold, while the process is not transparent without accountability mechanisms.

The right of the individual to own our privacy should be a basic human right, but it is in a very vulnerable position today. Therefore, the relevant governance policies need to be developed around the protection of human rights as the core (Karppinen, 2017). As stated in Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations (1948), ‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence.’ This should prevent arbitrary infringements by any company or governments.

From the platform perspective —— How do social media platforms quietly obtain your data?

As usual, you open TikTok on your mobile phone, start swiping up and down the screen, like videos or share them with your friends… This may make you enjoy the fun, but do you know that every action you take on TikTok is precisely recorded and saved in the database as a detailed portrait of you.

According to TikTok’s privacy policy, the personal information collected includes basic information, location information, payment information, historical behaviour, and even personal biometrics. Most of the data that we unconsciously send to the platform is actually the valuable resource that is like oil today (Flew, 2021).

Like most media platforms, TikTok users need to actively submit personal data in exchange for enjoying the platform’s services (Flew, 2021). The platform can recommend content that you may be interested in by analysing your data, which may bring you enough joy. However, the more accurately it can predict user preferences, the longer users will use it, and it can obtain huge profits through models such as embedded advertising. It is undeniable that the main goal of platforms collecting data is to maximise profits (Flew, 2018).

We cannot accuse companies of being profit-oriented, but it does not mean that they can be unethical. The recommendation algorithms and moderation mechanisms used by platforms such as TikTok are considered as ‘black box’, as users cannot clearly understand the operating logic, and even the government does not have absolute access to it (Suzor, 2019). This is the main concern of the American government.

Although TikTok CEO has emphasized that the ‘Texas Project’ can fully protect and store the data of American users in the U.S., the structural power it displays can still determine the behaviour of users (Karppinen, 2017). Users can only accept it passively unless they can abandon the use of TikTok.

From the user perspective – Do you really have control over your data?

Except for being stored on media platforms, our data is most likely to be passed on to third parties in exchange for economic benefits, as this is a highly valuable business resource for companies. This has even led to a widespread trading of personal data, even if some of it is illegal. However, most individuals who should have sovereignty over such data are unaware of it.

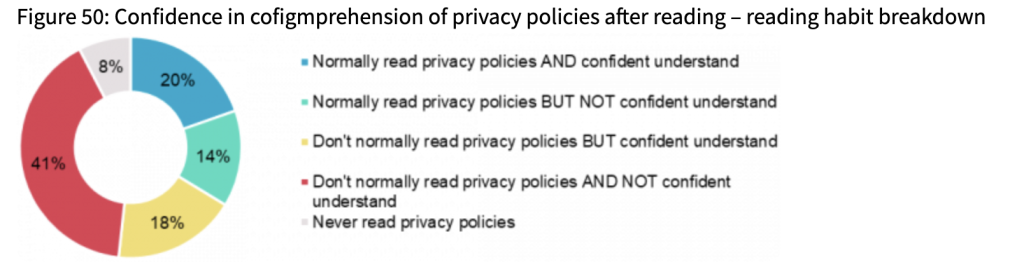

According to a Pew Research Center survey, more than 91% of users feel they have no control over their data and lost confidence on the media platform (Flew, 2021). Furthermore, most people choose to ignore reading the privacy policies or terms of service before using media platforms such as TikTok, as people are unwilling to spend time on them. Research by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner found that only 20% of Australians read privacy policies properly. When this unreasonable default agreement becomes normal, users’ awareness of privacy protection will gradually weaken (Steinfeld, 2016).

According to the theory of contextual integrity (Nissenbaum, 2015) the privacy that users need to protect is not the pursuit of absolute secrecy, but the appropriateness of information in specific contexts. More generally, when users use TikTok to watch videos and share their data, this is just leisurely entertainment time for individuals. However, the platform monitors user behaviour, collects data and even sells it during the same period of time. These two scenarios are completely different, and the cross-border transmission of data is against the user’s original willingness.

The situation is relatively more serious for TikTok. According to discussions in the U.S. House of Representatives, TikTok may be used by its parent company ByteDance to collect data or implant virus software (Lewis, 2024). This is also because the Chinese national intelligence law requires domestic companies to collect information for the government when it becomes necessary (Minges, 2025).

Crucially, even when most users are aware of privacy and data risks, individuals often feel angry but powerless. This is because most people believe that it requires the intervention from a higher authority, or accept the existence of this situation as it seems not to have caused any real actual damage. Furthermore, complex internal appeal procedures within the platform are also a barrier to users protecting our rights (Suzor, 2019).

The Privacy that has been Sacrificed

The TikTok incident has provided us with an important reminder about privacy security. The aim of this article is not to focus on geopolitical risks, but more importantly to identify the systematic privacy crisis that exists in our daily lives. If the TikTok ban continues to be implemented in the U.S., how can other American platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, protect the privacy of their users.

Today, restrictions on specific content and who should be the rule-setter are widely discussed by the public and the media (Suzor, 2019). However, users have no actual influence on the formulation of rules regarding individual privacy and data management. This is because the platform has almost unlimited rights, and users can only protest against the media company’s autocratic power (Flew, 2021).

This power is also reflected in the formulation of service and privacy agreements. The features of such agreements are very similar on different platforms, including lengthy text, complicated or professional legal terminology (Flew, 2021). All of them aim to generate sufficient business benefits. According to research by the Australian Consumer Policy Research Centre (Kearns, 2024), Australians need to spend 14 hours reading all the privacy policies they are faced within one day, which is so unbelievable! Moreover, even if users identify problems, they can hardly raise objections and are only forced to agree. This is because users who passively share data are in a peripheral position compared to the platform (Marwick & Boyd, 2018).

Contrary to the facts, media companies constantly want to hide their true positioning and try to maintain a good image to their users. Although they have the power to control the output of content, they are packaged to the public as simply a technology company (Flew, 2018). By displaying its neutrality, media companies seek to avoid regulation and liability (Suzor, 2019). For companies, there is nothing more cost-effective than protecting their reputations while gaining economic benefits. Fortunately, this appearance is gradually being revealed to the public. The fair access and distribution of data resources is still a key factor for users to legally protect our privacy rights (Karppinen, 2017).

Defend Your Right to Privacy

Depending on the issues we have discussed, you may already be concerned about your data privacy. However, simply uninstalling apps or adjusting privacy settings in the platform cannot be a real solution. What we need is a stronger and more comprehensive regulatory and governance mechanism for individual privacy (Minges, 2025).

Within the background of today’s increasingly serious global privacy crisis, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation can be seen as a relatively strict and comprehensive model. It clearly stipulates users’ rights to access and control their own data, including the right to be forgotten which allows data to be deleted (Karppinen, 2017). This is an example that other regions should follow.

In addition, ‘co-regulation’ and ‘soft law’ can be adopted as effective governance solutions. This means that there could be a third party to formulate and monitor rules after weighing the needs of different stakeholders (Flew, 2018). The advantage of soft law is to help these rules be developed to apply in emerging media platforms, rather than allowing them to exploit loopholes in traditional laws (Flew, 2018).

In an environment where most media platforms are now self-regulated, it is indeed difficult for them to fully develop rules that are satisfied by all stakeholders (Suzor, 2019). Therefore, the role of platforms in the multi-party relationship between users and governments needs to be more clearly and systematically defined, not just for TikTok.

This also requires the alertness of users regarding privacy and data security issues, as well as collective appeals to governments and platforms. Transparency and accountability mechanisms for digital governance will only be improved in this way.

Conclusion

Overall, TikTok’s struggle with the US government is not just a political battle between countries, but also a warning to all of us who use media platform about the vulnerability of our privacy. Simply blocking TikTok may temporarily reduce the threat for American users. However, the systemic crisis that exists on all digital platforms cannot be eliminated.

What we need are more effective privacy protection mechanisms and real control over our own data, not just an option to not use these platforms. This is equally important for users all over the world. Increasing transparency about the use of data by platforms and enhancing existing digital governance laws and accountability mechanisms are fundamental ways to make a positive change. Please remember that data privacy is a basic human right that we should all have, and it is also a responsibility that governments and businesses need to protect and uphold.

References

Adobe stock. (2025). Ethical hacking in action. https://stock.adobe.com/

Allyn, B. (2024, April 24). President Biden signs law to ban TikTok nationwide unless it is sold. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/04/24/1246663779/biden-ban-tiktok-us

Backlinko Team. (2025, March 8). TikTok Statistics You Need to Know. Backlinko. https://backlinko.com/tiktok-users

Davies, P. (2025, April 3). TikTok faces €500 million fine for illegally shipping European user data to China – report. Yahoo News. https://sg.news.yahoo.com/tiktok-faces-500-million-fine-150906554.html

European Union. (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/

Flew, T. (2018). Platforms on trial. InterMedia, 46(2), pp. 24-29.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms (pp. 72–79). Polity Press.

Hale, E. (2025, January 15). TikTok users in US flock to “China’s Instagram” ahead of ban. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/1/15/tiktok-users-in-us-flock-to-chinas-instagram-ahead-of-ban

Hamilton, D. (2025, January 20). How TikTok grew from a fun app for teens into a potential national security threat. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/tiktok-timeline-ban-biden-india-d3219a32de913f8083612e71ecf1f428

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights, pp.95-103. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835-9

Kearns, B. (2024, July 22). Privacy policies would take 14 hours to read each day | CHOICE. CHOICE; CHOICE Australia. https://www.choice.com.au/consumers-and-data/data-collection-and-use/who-has-your-data/articles/managing-your-privacy-report

Lewis, J. A. (2024). TikTok and National Security. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/tiktok-and-national-security

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction (pp. 1157–1165). University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism, Annenberg Press.

Minges, M. (2025, January 23). National Security and the TikTok Ban. American University. https://www.american.edu/sis/news/20250123-national-security-and-the-tik-tok-ban.cfm

NBC News. (2023, March 24). TikTok CEO describes “Project Texas” plan to store U.S. data “on American soil.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHG5VuSkl8A

Nissenbaum, H. (2015). Respecting Context to Protect Privacy: Why Meaning Matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

OAIC. (2020, September). Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey 2020. OAIC. https://www.oaic.gov.au/engage-with-us/research-and-training-resources/research/australian-community-attitudes-to-privacy-survey/australian-community-attitudes-to-privacy-survey-2020

Onysko, J. S. (2024, June 11). The Black Box Algorithm: Driving Interests and Shaping Perspectives in the Israel-Palestine…. Medium. https://joshuanysko.medium.com/the-black-box-algorithm-driving-interests-and-shaping-perspectives-in-the-israel-palestine-edfe6eec1245

PBS NewsHour. (2023, March 31). WATCH: Why a ban on TikTok won’t solve all data privacy concerns. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNRHuFP56Ig

RDNE Stock project. (2020). Defend Your Right to Privacy. In Pexels.

Steinfeld, N. (2016). “I agree to the terms and conditions”: (How) do users read privacy policies online? An eye-tracking experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(B), 992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.038

Suzor, N. P. (2019). “Who Makes the Rules?” In Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives, 10–24. Cambridge University Press.

The Project. (2022). TikTok Privacy Concerns As New Report Reveals How Much Personal Data Is Received From Users. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LCWk_WYKMr0?si=-uESHiu_XVRVJeEs

TikTok. (2025). Privacy and Security on TikTok. Tiktok.com. https://www.tiktok.com/safety/en/privacy-and-security-on-tiktok

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations; United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

Vladislava, B.-K. (2025). Innovative technology governance: hard rules for soft laws. Frontier Economics. https://www.frontier-economics.com/uk/en/news-and-insights/articles/article-i21147-innovative-technology-governance-hard-rules-for-soft-laws/

Weber, R. H. (2021, December 17). Co-regulation – Glossary of Platform Law and Policy Terms. Platformglossary.info. https://platformglossary.info/co-regulation/

Yu, E. (2023, August 25). Twelve nations urge social media giants to tackle illegal data scraping. ZDNET. https://www.zdnet.com/article/twelve-nations-urge-social-media-giants-to-tackle-illegal-data-scraping/

Be the first to comment