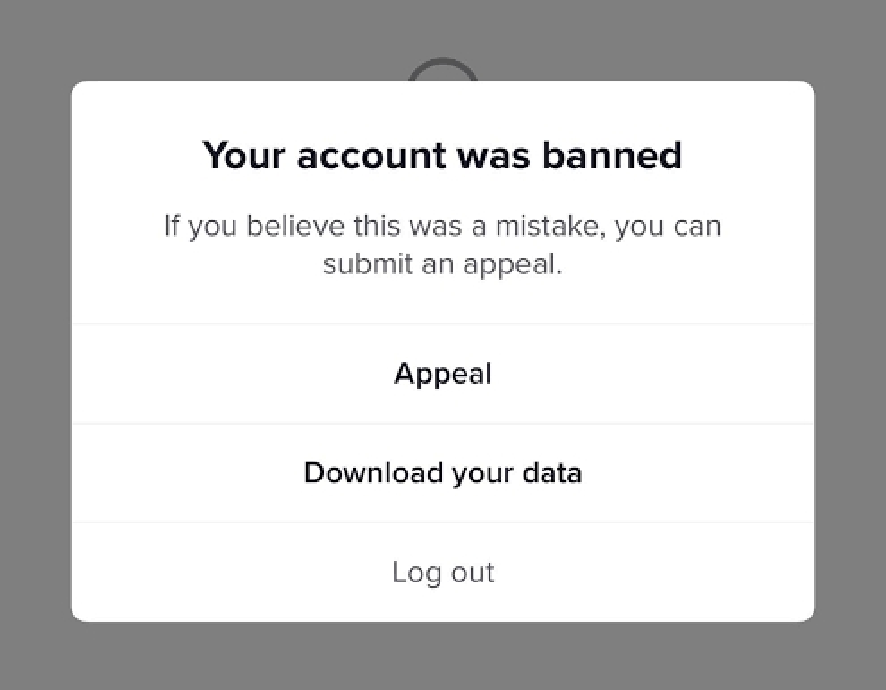

Have you ever been muted, restricted, or even banned on Weibo because you spoke out for feminism or supported the LGBTQ+ community?

Figure1: Source: Rednote post, unknown author (n.d.)

As one of the most influential social media platforms in China, Weibo’s public environment has been getting worse in recent years. Hate speech and hostility are spreading everywhere on the platform, especially against women and minority groups. What’s more ironic is that when you try to fight for the basic rights for these groups, you may be waiting for bans, streaming restrictions, and account blocked, while at the same time, those who post hateful and insulting comments are still active and even trending. Is this a failure of the platform’s censorship system, or is it the algorithm’s intentional bias?

Platforms Are Not Neutral: Terms of Service, But for Whom?

In most people’s opinion, public social media platforms like Weibo, Twitter, and Facebook are supposed to be places where people can express themselves freely. But in reality, every user must click “I agree” before logging in —agreeing to a long and complicated terms of service document. These rules may look like they are protecting users’ rights, but actually, they are legal tools that protect the interests of the company. As Suzor (2019) points out, “terms of service documents are not designed to be governing documents; they’re designed to protect the company’s legal interests” (p.11). When your account is blocked and you turn to the community guidelines for help, you may find that no one from customer service replies, or worse, you receive only cold, automated responses from an AI. It is the moment that you realize something important: it is not the users who have the power to explain the rules — but the platform itself.

What’s more important is that these platforms are not as neutral as they claim to be. On Weibo, many users have noticed that if they change their profile gender from “female” to “male”, the number of views and recommendations on their posts will increase significantly. This shows that the platform’s algorithm has a kind of unconscious gender bias—it treats the “male” identity as more trustworthy and worth spreading. This is not simply a failure of moderation—it is a reflection of how AI systems are designed to serve certain interests. As Crawford (2021) argues, “Artificial intelligence, in the process of remapping and intervening in the world, is politics by other means” (p. 20). What appears to be a neutral algorithm is in fact making political choices about whose voices get amplified and whose are ignored. On Weibo, some extreme male users constantly attack the feminist bloggers they dislike. To avoid the platform’s automatic content detection, they try to “code” their language, turning normal words into symbols of hatred. For example, they use “Quan Shi” (literally meaning “boxer”) as a sarcastic way to refer to feminists, or they create homophones, emoji combinations, or word changes to express their hate indirectly. This is similar to how “Karen” has become a symbol of troublesome middle-aged white woman on Twitter. A simple woman’s name was changed into a sexist label to mock and silence women. These types of speech don’t look rude on the surface, but are actually very toxic and discriminatory. That’s why they often escape the platform’s detection and punishment. Worse than that, there also exists very direct and violent language, like calling women “sow”, which is clearly abusive and sexist. These attacks are not only found in public comments but also happen through private messages, reposts, and online doxing. When the blogger blocks them, these users may even take revenge by exposing the blogger’s personal information such as real name, home address, or photos—a behavior known as “open box” (doxing). This turns online violence into real-life danger. It is just like the Gamergate case, where three women—Sarkeesian, Quinn, and Wu—were harassed, doxed, and forced to leave their homes (Flew, 2021). For the victims, the damage is not only mental, but also physical.

Zheng Linghua’s Death: A Tragedy Rooted in Digital Hate

Figure 2. Zheng Linghua smiling and playing ukulele before facing online hate on Weibo.

Source: BBC News (2023). China: Online abuse and death of a pink-haired girl sparks anger.

Zheng, a 23-year-old Chinese girl, posted a photo of her pink hair and celebrated her success in the graduate school entrance exam with her grandfather on Weibo. However, her photo was later reposted without permission and became a target for many hateful comments. People online used words like “crazy”, “mentally ill”, and “clown girl” to shame her. Some even said, “Girls with pink hair are all abnormal”. Even though Zheng tried to defend herself and reported the hate, the platform did not respond in time. According to the BBC (2023), her death caused a big public discussion about the hate culture on Weibo.The death of Zheng Linghua in early 2023 is not just a personal tragedy, but a powerful example of how hate speech on social media can lead to real-life harm.

This case shows what Crawford (2021) said in The Atlas of AI: “AI systems are ultimately designed to serve existing dominant interests. In this sense, artificial intelligence is a registry of power”(p. 8). Weibo’s basic algorithm and content review system did not protect her personal rights. Instead, they helped make her more visible to attackers because of its mechanism. In this way, the platform actually supported the power imbalance in society. In the report Facebook: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific, Ghoshal et al. (2021) also point out that “Facebook’s definition of hate speech still leaves gaps that allow disempowering content to remain” (p.1). The hate against Zheng is one of these cases—where sexist and harmful comments were not identified and blocked by the system, but continued to spread. Carlson and Frazer (2021) believe that social media “can be used to reproduce power hierarchies and exacerbate unequal power relations” (p. 14). This idea also fits the situation of Zheng. As a young girl who worked hard to succeed, she should have been supported. But because of her appearance and her way of expressing herself, she became a target. She was not hated for what she said, but for daring to say anything at all.

What makes the Zheng Linghua case even more disturbing is not just the hateful comments she received, but how little action the platform took to protect her. This reflects a deeper problem in platform governance. As Flew (2021) argues, platforms are no longer just private companies—they are de facto regulators of online expression. They set the rules for what can be said, who can be heard, and who gets silenced. Yet, their rules are often vague, inconsistent, and hidden from public scrutiny. Most importantly, these rules are not designed to protect vulnerable users but to reduce corporate risk. The failure of Weibo to respond effectively to hate speech is not just a technical problem. It is a reflection of how power is distributed in digital spaces. This means that when users like Zheng seek justice or protection, they are not treated as citizens in a democratic public space but as customers with no real rights. The platform can silence you at any time, but it is not required to protect you when others attack. This imbalance of responsibility and power makes social media platforms dangerous places for women and marginalized groups. If we don’t demand greater transparency, accountability, and fairness, these platforms will continue to amplify hate while hiding behind the excuse of “neutrality”. The algorithm helped these hate contents go further and spread faster. In the end, this tragedy shows how the whole system—platform censorship, algorithm design, comment review, user reporting—failed. Hate is not an accident on the platform. It becomes part of the system. Every click, repost, or like makes hate stronger. Zheng’s death reminds us that hate speech is not just words—it can kill, and platforms’ inaction is also an accomplice.

Platform Governance and the Illusion of Protection

Source: Brent Lewin/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

What’s worse is that Weibo’s traffic system is based on what can be called a “hate economy”. The algorithm prefers extreme emotions and gives more exposure to angry or offensive posts because they make people react and stay longer on the app. This leads to more attacks on women, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized users. The more people click, the more hate spreads. In this digital world, hate speech and the recommendation system change the way people think. They make everything about taking sides, turning gender into a fight. In this way, hate speech is supported, repeated, and amplified. It creates an emotional loop that weakens social unity and makes real discussion more and more difficult.

When women try to fight back against hate speech, their voices are often suppressed by the platform’s invisible and biased moderation system. Even when they are simply responding to private harassment or defending themselves, their comments are more likely to be flagged, deleted, or hidden with a notice like “This comment violates community guidelines”. On platforms like Weibo, power is clearly unequal. Male users tend to receive more exposure, tolerance, and algorithmic support, while women are expected to stay quiet—like traditional housewives whose value lies in obedience and silence. This is not just a bug in the system; it is a feature of the way the system is designed. As Carlson and Frazer (2021) point out, “Social media is not a neutral or necessarily safe space for Indigenous peoples. It can be used to reproduce power hierarchies and exacerbate unequal power relations” (p. 14). The same is true for gender dynamics: Weibo presents itself as an open public forum, but its algorithms and moderation tools actually reinforce existing social inequalities. Instead of empowering all users equally, it rewards those who already hold power and silences those who challenge the status quo.

Breaking the Cycle: Technical and Policy Reforms

But silence has never been the nature of women. Banning them will not erase their voices. Even when told to shut up, women always find new ways to speak, resist, and create. Hate speech is not just words—it creates real emotional pain, mental health damage, and in some cases, leads to tragic outcomes. When intelligent and courageous women are forced into silence, the entire quality of online dialogue suffers. We don’t just lose individual voices—we lose critical perspectives, empathy, and truth. To break this vicious cycle, change must happen on multiple levels. From a technical perspective, platforms should redesign their algorithms to prioritize safety and fairness, not just engagement. Machine learning models must be trained to detect covert hostility, sarcasm-based bullying, and pattern-based harassment, not only explicit slurs. Natural language processing tools can also be used to identify emotional tone and intent. On the level of policy, content moderation processes should become more transparent, appealable, and participatory. One idea is based on community aspect. Some platform users can be allowed to participate in the assessment and form a jury. When your account is blocked, your complaint can be submitted to a panel of judges to evaluate whether it violates community conventions and can be successfully restored, rather than facing cold AI or waiting for the platform customer service that never responds as if it didn’t exist. This “jury of peers” would offer a more democratic approach to moderation and help restore trust.

At the same time, users are not powerless. As members of online communities, we have the ability—and the responsibility—to shape the digital spaces we live in. We can report hate speech, support marginalized voices, share stories that deserve to be heard, and speak out when others are silenced. But action goes beyond reporting. We can create educational content, organize online campaigns, start petitions, and work together to demand better platform rules. Even small actions, when multiplied by thousands of users, can have a powerful effect.When more people refuse to accept hate as “normal,” the platform will have no choice but to listen. Change does not only come from top-down regulation—it can also emerge from everyday digital resistance. Feminist bloggers, LGBTQ+ creators, and ordinary users who refuse to be silenced are already rewriting the rules from the bottom up. Their courage should not be punished or ignored; it should be recognized, protected, and amplified. These voices are essential to a healthier internet—and a more just society.

We also need to recognize that platforms should not just “hear” users—they should respond, include, and reform. True accountability means building open channels where users can give feedback, challenge decisions, and influence policy. It means that platforms must move beyond vague promises and show real transparency in how content is moderated, how algorithms work, and how bias is addressed. After all, the internet was meant to connect us—not divide us through fear and violence. And platforms and algorithms are not separate from society—they are shaped by human choices, values, and priorities. If we want a digital world with less hate, we must actively build systems that do not reward outrage and cruelty, but instead uplift fairness, care, and dignity. That requires not only better technology, but better people behind that technology. Otherwise, hate will remain the loudest voice in the room, while those who most need to be heard are pushed further into silence.

References

References

BBC News. (2023, March 7). China: Online abuse and death of a pink-haired girl sparks anger. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-64871816

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2021). Being Indigenous online. Macquarie University. https://www.indigenousx.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Being-Indigenous-Online-Report.pdf

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. John Wiley & Sons.

Ghoshal, A., Whiting, D., Perera, J., & Ula, M. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. https://globalextremism.org/reports/facebook-asia/

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our digital lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Be the first to comment