Have you ever experienced what seem to be a mundane weekend: you open Instagram, wanting to post a collection of candid pictures on the month of March. Unable to think of an edgy caption to impress your followers, you turn to ChatGPT with the prompt ‘write a witty caption for a March dump post on IG’. After posting the images, you get back on your laptop, browse Netflix, and look for shows to binge on the weekend. Overwhelmed by the abundance of content, you ask ChatGPT for show recommendations. It lists out a couple of shows, including ‘Love Island,’ a show you have never heard of. Intrigued, you ask for the premise, and ChatGPT provides a short description along with links to more information. Hooked, you decide to watch the show.

In just 15 minutes of this seemingly mundane weekend, you have utilized generative artificial intelligence (AI) multiple times. According to an article done by The Washington Post and researchers from University of California, Riverside (2024), it illustrates that a 100-word email generated by ChatGPT once requires 519 milliliters of water, which over a week adds to 27 liters. While it is challenging to quantify how an AI prompt affects water usage, the rapid innovation of AI and its environmental footprint is a rising concern among researchers and environmentalists (Berreby, 2024)

This piece will argue that behind the harmless AI interactions lies a troubling pattern of exploitation that current governance frameworks fail to address. By examining ChatGPT’s AI systems, this piece will explore three critical forms of exploitation: environmental extraction, labor exploitation, and privacy violations. The governance may have fallen short in preventing them, but by understanding the gaps, we can better advocate for ethical AI that enhances humanity instead of exploiting them.

AI and its Risks of Exploitation

To understand the concerns better, let’s examine ChatGPT, an unstoppable innovation which usage has ballooned even in the first two months of its launch with 100 millions users (Milmo, 2023). While AI systems like ChatGPT has improved productivity, enhance the lives of people with disability, optimizing a business’ profit, and many other positive case studies, they come with significant hidden costs. Kate Crawford, in her book “The Atlas of AI” (2021), explicitly argued that AI is an extractive industry that demands energy resources, cheap labor, and data exploitation. But how exactly do AI systems like ChatGPT ‘extract’ said aspects? Let’s break it down one by one.

Environmental extraction & the physical reality of “cloud” computing

ChatGPT’s extensive use of water that was illustrated on the beginning of this writing is not just an abstract concern. The common misconception is that AI systems like ChatGPT runs on cloud technology when in fact, AI requires massive computational power with physical resources such as lithium and batteries to train these large systems in a form of data centers that leads to massive energy consumption and water waste (Crawford, 2021). Due to these physical aspects, training a single model alone can result in over 284,000 kilograms of CO2 and consumes 700,000 liters to cool data centers (Regilme, 2024). Your simple request for Instagram caption may contribute to this environmental impact.

Labor exploitation & the human workers behind the “machine”

ChatGPT’s seemingly machine-driven technology relies heavily on human labor, often performed under exploitative conditions (Crawford, 2021). This exploitation is particularly pronounced in the Global South, creating what Regilme (2024) calls “AI colonization”, where AI benefits primarily the elite Global North at the expense of the workers of the Global South. A particularly troubling example was found by TIME investigations, where OpenAI (ChatGPT’s parent company) outsourced labor workers from the global south like Kenya under precarious working conditions to moderate the system to become less toxic with only $2 per hour pay (Perrigo, 2023). Considering the amount of work revolving disturbing contents they have to moderate, would you think $2 per hour to ensure your interaction with ChatGPT remain safe fair?

Privacy violations: Your data as main source of information

ChatGPT’s training process also involves scraping data from various sources which may include personal data without proper consent due to its Large Language Models (LLMs) that requires huge amount of data training, which raises concerns on privacy violation and exploitation on users’ data (Wu et al., 2024). When you ask ChatGPT for movie recommendations, it drew on this massive dataset that’s likely to include private information. The privacy implications are profound, your data become a resource to be extracted, refined, and sold without little to no transparency. How’s it used? Who profit from it?

Now that you realize you might have been interacting with a system built upon these extractive foundations, you might wonder: why do these risks and concerns remain invisible to users?

AI Governance: Current Global Landscape

You’d think that with such significant impacts on the environment, labor rights, and privacy concerns, there would be clear laws for AI like ChatGPT to operate. The reality is AI governance is a multi-layered effort, involving multiple stakeholders, including and especially the government. Even so, approaches of every nation in implementing regulations on AI may differ.

The EU AI Act, often dubbed as the prime global standard for AI regulations, is a joint effort by the European Commission, European Parliament, and the Council of European Union. The EU AI Act, applied to countries under the European Union, categorizes AI systems by risks levels. On the other hand, the USA has opted for a more decentralized style of regulation, with various agencies and sectors handling different aspects of AI (Anderson et al., 2025). Other countries, especially on the Global South, are actively developing AI regulations, with some aligning to the EU AI Act, and others create national strategies (Reuters, 2023). There are international organizations such as Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and UNESCO that issue frameworks to promote ethical governance and international cooperation (Reuters, 2023). However, it raises the questions of an apparent global governance gap. For instance, what happens when AI systems like ChatGPT is developed in the US, being deployed globally, and contracts third party in Kenya? Which regulations should ChatGPT apply?

Even more concerning is what these frameworks ignore: they prioritize user-facing issues such as bias and accuracy but largely overlook the impacts that are conveniently hidden. For one, issues of the exploitation of workers who perform crucial data labelling and content moderation tasks that occur due to legal grey areas in digital platforms (Regilme, 2024). Neither the EU AI Act nor the US voluntary frameworks require disclosure labor practices, let alone on carbon emissions or water usage, creating regulatory blind spots that resulted in AI governance falling short.

Why Has AI Governance Fallen Short?

Governments have struggled to address these issues and there are several factors, but each of them has its own contradictions.

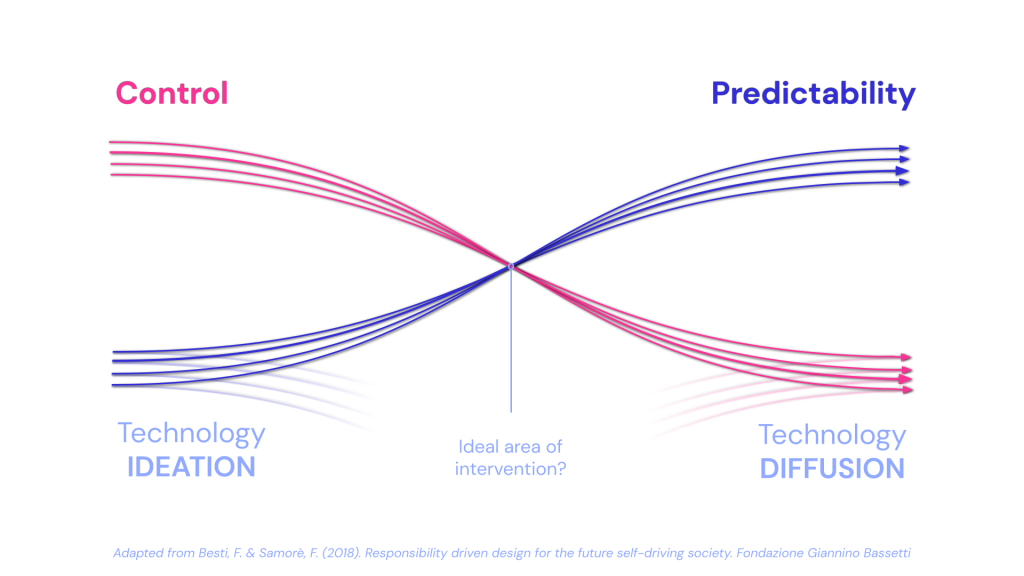

The Collingridge dilemma: Too early or too late

The first apparent factor is AI’s rapid development that outpaces the ability of regulations to adapt. This is a concept introduced by David Collingridge on his book “The Social Control of Technology” (1981), later coined as the “Collingridge’s dilemma”, where we can regulate technologies before we know their harms, but once we know the harms, the technologies would be too embedded in society to easily change.

This dilemma is not unique to AI; it is a common challenge in the governance of any rapidly evolving technology. What makes AI particularly challenging under Collingridge’s framework is its dual nature as both software and hardware. Systems like ChatGPT can be deployed globally within days yet rely on physical infrastructure that takes years to build.

The private sector & profit incentives

Another factor as to why AI governance has fallen short is on the hands of the AI tech companies, who play a central role in AI development. Their decisions are mainly driven by monetization over societal concerns (Chinen, 2023). Even so, they often conceal them as having mitigated societal risks.

Take ChatGPT who champions their mission of building safe AI systems that limit harmful content: they’re doing so on the expense of their Kenyan third-party labor workers. This reveals a troubling disconnect between public messaging and actual practice.

“Black Box” and the limited public awareness

The final factor is our very own limited awareness of AI systems. Public awareness regarding AI literacy is exceptionally important on AI governance. Effective AI governance requires public engagement to understand and scrutinize AI systems (Boakye et al., 2025; UNESCO, 2021). However, how can we be critical of AI systems when it operates as ‘black boxes’, a concept by Pasquale (2015) that refers to AI’s complex machine-learning models as difficult to understand and lacking in transparency? Without sufficient AI literacy, how are users expected to hold technology companies like ChatGPT accountable for their actions or lack thereof?

These factors lay out a series of chicken-and-egg questions: Should AI regulations come before or after technology development? Should economic profit be a priority over societal well-being? Should public awareness of AI precede or follow the transparency of AI systems? These dilemmas are inherent in AI governance, so what tangible solutions should be enforced?

A Vision for Better Governance

With these challenges in mind, what might better AI governance look like? While this writing won’t claim to have all the answers, it is certain that a better future for AI governance should be built upon principles of human-centric inclusivity and sustainability.

Mandatory ethical assessments

A core element is the adherence to ethical principles in AI development and deployment. Instead of vague commitments to “ethical AI”, governance could include mandatory assessments before deploying AI systems like ChatGPT with input from different stakeholders: academia, industry, civil society, and marginalized groups.

While the works of EU AI Act, OECD AI, and UNESCO’s Recommendations of Ethical Intelligence already take step in this direction, there still needs a recognition of the need for context-specific regulations, particularly in the Global South, who are often excluded or even underrepresented in discussion regarding AI regulations which may lead to a widening global AI divide (Boakye et al., 2025).

Environmental transparency and accountability

A better AI governance should also prioritize environmental sustainability that includes assessing and reducing the direct and indirect environmental impact of AI such as carbon footprint, energy consumption, and other environmental consequences of raw material extractions (UNESCO, 2021; Verdecchia et al., 2023).

What if companies had to disclose how much water and energy each AI data center required, just as they report financial costs? Google, Meta, and Amazon has consistently release their annual environmental report, but these didn’t include AI-specific impacts. If only you could see ChatGPT’s environmental cost for every query input, the global society would have put so much pressure on ChatGPT for more efficient systems.

Labor protection across the AI supply chain

Governance should extend the frameworks beyond traditional employment regulations to include all works in the AI supply chain. This means calling for transparency requirements not only to those working in the AI companies, but also the conditions of the outsourced or contracted workers, like ChatGPT’s Kenyan content moderators. Fair compensation, healthcare support services, and maximum exposure to harmful contents should be proposed as industry standard.

Most importantly, better governance requires collaborative effort by government bodies, international industries, and civil society. With that said, where do we jump in in this vision of better AI governance?

Users’ Responsibilities in AI Governance

As users, we have more power than we might think. While we can’t offer a single solution to complex challenges, we can:

- We can empower other individuals with the knowledge about AI usage and its extractive nature and risks.

- Advocate for AI companies to be more transparent with their exploitative practices and demand changes for the betterment of society.

- Use AI systems like ChatGPT more intentionally rather than for trivial tasks.

- Engage in conversations about ethical AI.

Rather than avoiding AI entirely, we should call for a more equitable relationship with these technologies, one that acknowledges and minimize exploitations rather than hiding behind sleek interfaces and clever responses.

The next time you ask an AI for an Instagram caption or movie recommendations, take a moment to consider the hidden infrastructure behind that interaction. Think of the data centers consuming water to generate those witty words or the labor workers moderating data under concerning conditions. By becoming more conscious users, we can push AI that truly enhances humanity rather than extracting from the most vulnerable.

Reference List

2023 Amazon Sustainability Report. (2023). Amazon. https://sustainability.aboutamazon.com/2023-amazon-sustainability-report.pdf

AI Act. European Commission. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

Anderson, H., Cornstock, E., & Hanson, E. (2025). AI Watch: Global regulatory tracker – United States. White & Case. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/ai-watch-global-regulatory-tracker-united-states

Berreby, D. (2024). As Use of A.I. Soars, So Does the Energy and Water It Requires. Yale School of the Environment. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://e360.yale.edu/features/artificial-intelligence-climate-energy-emissions

Boakye, B., Singh, S., Drake, G., Coombs, H., Britton, L., Adams, R., Medon, F., Eitel-Porter, R., & Mokander, J. (2025). How Leaders in the Global South Can Devise AI Regulation That Enables Innovation. Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://institute.global/insights/tech-and-digitalisation/how-leaders-in-the-global-south-can-devise-ai-regulation-that-enables-innovation

Building an accessible future for all: AI and the inclusion of Persons with Disabilities. (2024). United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://unric.org/en/building-an-accessible-future-for-all-ai-and-the-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities/

Chinen, M. (2023). The International Governance of Artificial Intelligence (1 ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800379220

Chui, M., & Yee, L. (2023). AI could increase corporate profits by $4.4 trillion a year, according to new research. McKinsey Global Institue. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/overview/in-the-news/ai-could-increase-corporate-profits-by-4-trillion-a-year-according-to-new-research

Collingridge, D. (1981). The social control of technology. Open University Press.

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI : Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=6478659

Domanska, O. The EU AI Act: a new global standard for artificial intelligence. Business Reporter. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://www.business-reporter.co.uk/technology/the-eu-ai-act-a-new-global-standard-for-artificial-intelligence

For a better reality: Meta 2024 Sustainability Report. (2024). Meta. https://sustainability.atmeta.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Meta-2024-Sustainability-Report.pdf

Google Environmental Report. (2024). https://sustainability.google/reports/google-2024-environmental-report/

Milmo, D. (2023). ChatGPT reaches 100 million users two months after launch. The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/feb/02/chatgpt-100-million-users-open-ai-fastest-growing-app

Papagiannidis, E., Mikalef, P., & Conboy, K. (2025). Responsible artificial intelligence governance: A review and research framework. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2024.101885

Pasquale, F. (2015). INTRODUCTION. In The Black Box Society (pp. 1-18). Harvard University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0hch.3

Perrigo, B. (2023). Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic. TIME. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/

Pranshu, V., & Tan, S. (2024). A bottle of water per email: the hidden environmental costs of using AI chatbots. The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/09/18/energy-ai-use-electricity-water-data-centers/

Regilme, S. S. F. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Colonialism: Environmental Damage, Labor Exploitation, and Human Rights Crises in the Global South. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 44(2), 75-92. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2024.a950958

Reuters, T. (2023). Is AI regulated in Australia? What lawyers should know. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://insight.thomsonreuters.com.au/legal/posts/is-ai-regulated-in-australia-what-lawyers-should-know

Somers, M. (2023). How generative AI can boost highly skilled workers’ productivity. MIT Management Sloan School. Retrieved 7 April 2025 from https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-generative-ai-can-boost-highly-skilled-workers-productivity

UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. S. a. C. O. United Nations Educational. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380455

Verdecchia, R., Sallou, J., & Cruz, L. (2023). A systematic review of Green AI. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1507

Wu, X., Duan, R., & Ni, J. (2024). Unveiling security, privacy, and ethical concerns of ChatGPT. Journal of Information and Intelligence, 2(2), 102-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiixd.2023.10.007

Be the first to comment