You’ve probably been in a situation where a child opens YouTube to watch a cartoon and an hour later unknowingly clicks into a strange, even disturbing video. Sometimes it’s a conspiracy theory interspersed with a Minecraft game, sometimes it’s a spoof of Peppa Pig, with bizarre images and outrageous content. Behind all of this, there’s often an unseen “driver” – Algorithm.

My brother is a living example. About a fortnight ago, I walked into the living room and saw him brushing an animated video on Jitterbug, which looked quite normal. But then I swiped down a few recommendations and suddenly the content started to get weird, and there were even conspiracy theories about “humans being manipulated”. He didn’t actively search for these things, but just followed the recommendations and kept scrolling. This scene gave me the creeps and my mom also began to worry. This got me thinking: What are children exposed to online daily? Who is manipulating their attention? And more importantly – what can we do about it?

Next, I want to explore how algorithms and AI systems can silently influence and shape children’s digital upbringing. Together, we’ll look at how platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and even the highly popular Xiao Tian Cai (Little Genius) smartwatches in China, collect data on children, make personalised content recommendations, and unwittingly push them into a world of harmful, even false, information. This is not just a question of “screen time”, but a deep-rooted issue involving platform governance, digital rights and child protection policies.

Small Eyes, Big Data — Children and the Privacy Trade-Off

Let’s start with the most basic, yet most overlooked question – where does the data come from? Where does their privacy go?

You may never thought about the fact that every click, every second, and every swipe your child makes on the internet doesn’t just happen quietly. These actions are recorded by the platform and turned into a string of data. And then what? This data is packaged and analysed to create a “user profile” of the child: who likes watching dinosaurs? Who is interested in blind boxes? Who tends to click on stimulating content? Then, adverts, video recommendations, and games to entice…… are precisely “fed” to them (Livingstone & Third, 2017).

- Children’s data leaks are a growing problem(Picture:SECRSS)

The most disturbing thing is that all this often happens without the knowledge of parents and children. You think your child is just watching a cartoon, in fact, their data has long been quietly “run away”.

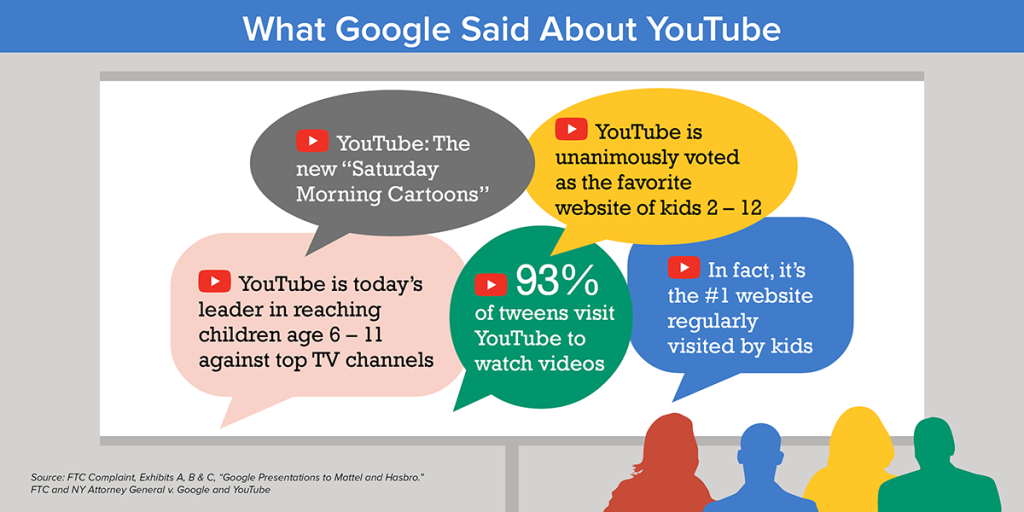

This is not alarming: in 2019, YouTube was heavily fined $170 million by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for illegally collecting data on children under the age of 13 (Federal Trade Commission, 2019). They used cookies to track children’s viewing behaviour and used this data to target advertising. To put it bluntly, they were making money by treating children as “mini-customers” – children who didn’t even know what the “I agree” button meant.

- It highlights YouTube’s awareness of child-directed content on its platform, with the company knowingly serving targeted advertisements on these channels despite being informed that the content was aimed at children and the platform’s violation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). (Picture:FTC)

There are similar issues in China. Remember the Little Genius Phone Watch? Many parents saw it as a “digital age security blanket”, but a few years ago it was exposed as having serious privacy issues. Media investigations revealed that not only were these smart devices collecting children’s location, voice, call logs and even behavioural tracks, but the level of encryption of this information was “virtually non-existent” (Tencent News, 2025). If the data is stolen by hackers or misused by platforms, the consequences are unimaginable.

Some might say: there are laws, aren’t there? True, COPPA in the U.S. and the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in China set legal baselines (Lyu & Chen, 2022). Sounds reasonable, right? But here’s the thing – the pace of technological development is way ahead of regulation. Platforms are coming up with all sorts of ways to “play”, and regulators are lagging behind in their response, and enforcement is often difficult.

In this digital age where data is king, we can’t help but ask: kids, is there a real sense of “privacy”? Or, if the platform’s default is that every user is a “can be analysed, can be recommended, can be monetized” data unit, are those who are still young, cognitively shallow children not from the outset in the most vulnerable position of the digital ecology?

Ultimately, the issue of privacy is not just about “a piece of data being stolen”, but about how children will grow up, make choices and express themselves in an algorithm-driven world. If even their attention in childhood is “predetermined” by platforms, how much real autonomy will they have as adults?

The Algorithm Knows Best? — AI Governance and the Illusion of Choice

How does a child go from watching Peppa Pig, slipping and sliding, to clicking on a video that says “the earth is flat” or “the new coronavirus is fake”? It may sound like you skipped ten episodes, but the answer is simple: algorithms.

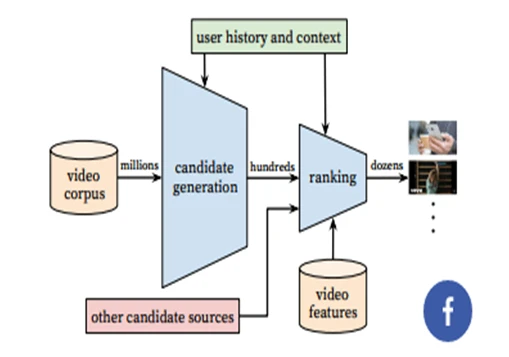

- This diagram shows the architecture of YouTube’s recommendation system, which retrieves and ranks a small number of recommended videos before showing them to the user. (Picture:infoq)

The platform’s algorithm doesn’t “judge” whether the content is appropriate or not, it just looks at click-through rate, viewing time and user reaction. And if outrage, speed, and shock increase watch time, that’s what gets pushed (Noble, 2018). Over time, children are pushed into an increasingly biased stream of content – a rabbit hole carefully mined by the algorithm.

Don’t get me wrong, we don’t see algorithms as “evil masters”. Algorithms don’t make value judgements; they can recommend quality content such as scientific experiments, artistic creations and historical stories. Maybe it’s even more informative than the Science Channel you watched as a kid. When I was a kid, if I wanted to find some interesting learning resources, I would either watch the “Popular Science Channel” on TV or browse through the children’s encyclopaedia in the Xinhua bookstore. The content was small, the updates slow and the choices limited. Nowadays, kids can just click on an app and there’s a huge amount of content waiting for them – interesting and interactive, and it’s really hard not to be jealous.

But the problem is that the primary goal of the platform’s algorithm is not to “educate” people, but to “engage” them. The more exciting the video, the faster the pace, the more exaggerated the style, the more likely it is to be recommended. As the laugh-out-loud factor increases, the plot becomes more outrageous, step by step pushing children into a world of curiosity, false and even harmful information.

Do you remember the “Elsagate” incident ? There were a lot of videos that looked like they were for children, with Spider-Man, Frozen, and Peppa Pig on the cover, but the content was fighting, kidnapping, and even implied violence or sexual innuendo (Bridle, 2017). The algorithms don’t “understand” the content, they just know – it’s clicked, it’s watched, it’s got a good retention rate, so they keep pushing it.

- The “Elsagate” incident exposed the serious risk of children being exposed to inappropriate content online, raising concerns about the responsibility of platforms, the regulation of content and the need to strengthen the protection of young viewers. (Picture:Guancha)

There are similar problems in China. For example, Douyin (TikTok’s sister app) has a “teen mode” that appears to have very strict controls: time limits, content filtering and identity verification. Sounds safe, right? But in practice, kids can break through the defences in minutes by setting the system time and logging in with their parents’ accounts. Once in “adult mode”, the recommended stream immediately switches to another world: live plastic surgery, fast weight loss, reward anchors, even mixed with some soft porn (Zhang & Feng, 2023). This content is not for children, but the algorithm does not care about your age, only your click rate.

- The algorithm is not “bad”, it just “doesn’t know you are a child”.

- In its eyes, there is no difference between “children” and “adults”, only “user labels” and “traffic conversion”. It will not ask “Are you ready”, it will only ask “What else do you want to see”.

So when children unknowingly slip down the rabbit hole created by the algorithm, the question is no longer “Is this video good”, but rather – is the whole recommendation mechanism designed as a “braking system” for children? Are there any boundaries? Is anyone really responsible?

Behind the Fun: What Kids Really See Online

We often say that it’s OK for children to watch “cartoons” and “funny videos” on the internet. But the question is – is what they see really just “cats and dogs”?

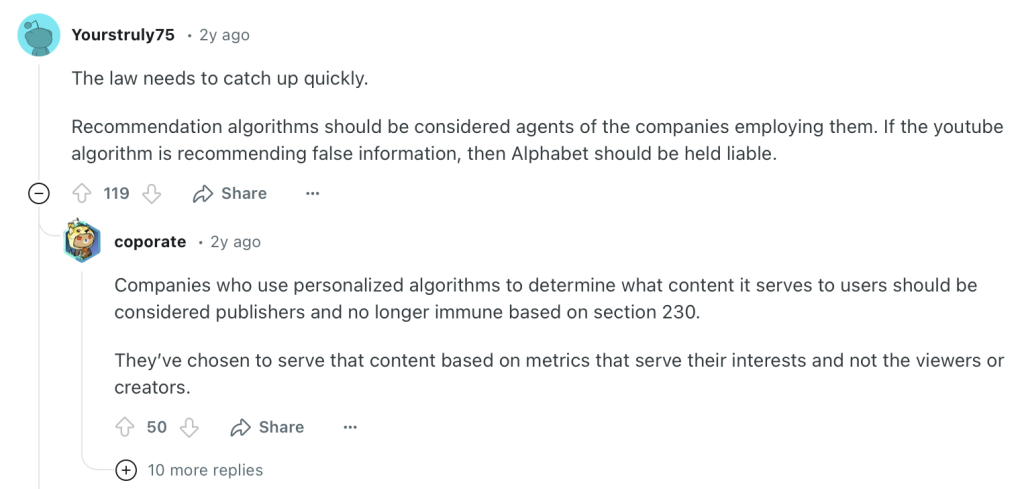

- The BBC World Service video “Bad Science: AI used to target kids with disinformation on YouTube” exposes how YouTube’s algorithm can promote misleading or harmful content to children, including conspiracy theories disguised as educational or entertaining videos.

- Discussion about this vedio on Reddit (Picture:Screenshot from Reddit)

For example, The Atlantic reported that some children, while watching Minecraft game videos, unknowingly clicked into the QAnon conspiracy theories, such as “the government is using 5G to manipulate people”, “COVID hoax” and so on (Zadrozny & Collins, 2021). It’s not something a child is actively looking for, it’s something an algorithm delivers with precision.

- So what we used to worry about was, “What are kids going to see online?”

- And now it’s more appropriate to ask, “What is the internet planting in our children’s minds?”

It’s a reality we have to face: algorithms don’t tell children what’s real and what’s biased; they just tell them – what else do you want to see and I’ll give you more.

This is not something that can be solved by saying “set teen mode”, it’s a long-term battle about education, platform responsibility, algorithm transparency and digital literacy. It may only take a few swipes for a child to fall down the algorithmic rabbit hole, but we need to do much more to get them out.

What Needs to Change?

We can’t expect a ten-year-old to understand “what data rights are”, just as we can’t expect them to understand nutritional labels in order to plan their meals. In this digital world of information overload and complex recommendations, it’s irresponsible to leave children to fend for themselves.

Of course, parents and teachers are still important, but we also have to admit that this is not a problem that can be solved by “guarding the children”. This is a systematic project that requires the joint participation of the platform, the government, the education system, technology developers and even society as a whole.

If the platform misuses children’s data and allows content to spread, the consequences can’t be limited to “criticism and education”. A truly effective sanction mechanism should make the platforms pay a substantial price, whether in money or reputation. Otherwise, platforms will never change and will only include “child protection” in their annual reports rather than making real changes.

At the same time, we need to make “media literacy” part of basic education, so that children can learn to spot online rumours, understand the logic of algorithms and judge the truth of information, just as they learn to read and write. More importantly, this is not just a matter for children – adults need to learn together, because this algorithm-driven world is our shared habitat.

- Many children browse Youtube and other websites independently. (Picture:Pinterest)

Don’t let algorithms be the director of your child’s childhood

We often say that “children are the future”, but the truth is that they are already living in a future world woven by algorithms. Our real task is not just to “protect” them from being misled, but to help them develop a sense of trust in the world.

The world is not perfect, but it should at least be about rules, responsibility and humanity. No matter how powerful the algorithm, it should not be the “director behind the scenes” of a child’s development.

What we need to do is draw clearer lines of responsibility, promote a more transparent recommendation mechanism, but also let more adults into the “workings of the world” to build real consensus. It is only when we get serious about these seemingly technical but really valuable issues that children will be able to come out of the rabbit hole and return to a path of growth where they have the right to choose, the power of judgement and hope.

References

Bridle, J. (2017, November 6). Something is wrong on the internet. Medium. https://medium.com/@jamesbridle/something-is-wrong-on-the-internet-c39c471271d2

Federal Trade Commission. (2019, September 4). Google and YouTube will pay record $170 million for alleged violations of children’s privacy law. Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2019/09/google-youtube-will-pay-record-170-million-alleged-violations-childrens-privacy-law

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Livingstone, S., & Third, A. (2017). Children and young people’s rights in the digital age: An emerging agenda. New Media & Society, 19(5), 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816686318

Lyu, H., & Chen, X. (2022). The Personal Information Protection Law of China and its implications for children’s privacy online. Journal of Law & Technology, 39(2), 214–231.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The need to know. In The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information (pp. 1–18). Harvard University Press.

Tencent News. (2025, March 1). Smartwatches for kids leak sensitive data: Experts call for urgent regulation. Tencent News. https://tech.qq.com/article20250301

Zadrozny, B., & Collins, B. (2021, January 16). YouTube’s algorithms help spread conspiracy videos to children. The Atlantic.https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/01/youtube-algorithms-qanon-kids/617686

Zhang, Y., & Feng, Y. (2023). Teen mode or trapdoor? Examining algorithmic bypasses in Chinese short video apps. China Digital Times, 45(3), 101–117.

Be the first to comment