“Freedom of speech does not protect you from the consequences of saying stupid shit.” — Jim C. Hines

Introduction

In modern society, people are used to opening social media every day to share their feelings, comment on hot topics, and watch short videos. The seemingly relaxed and enjoyable entertainment life can cause tragedy in the online world. While media platforms bring freedom to people, they also lay the foundation for hate speech and online abuse. When problems occur, everyone is asking: Whose fault is this? Is it the netizens who make malicious comments, or the platform that allows the spread of speech?

From the pink-haired girl who committed suicide after being cyberbullied to the man using social media to launch anti-Semitic attacks on parliamentarians, these incidents have made people reflect on their own words and deeds while blaming the platform for the failure of supervision. This blog will take you to explore the complex relationship between individuals and platforms behind hate speech and online abuse. In cyberspace, how should rights and responsibilities be reasonably controlled?

The Freedom Trap

In the digital media era, individual speech is widely disseminated through online platforms. Benefiting from the characteristics of electronic media that break the limitations of time and space, people can speak freely around the world and express their opinions on various events. However, the “freedom” also increases the possibility that individuals become the source of hate speech and online abuse.

- Hate speech generally refers to derogatory, threatening or discriminatory speech against a specific group or individual, involving race, religion, gender or other identity characteristics.

- Online abuse is the use of digital technology to harass, intimidate or humiliate others, including through social media, text messages or emails.

When hate speech and online abuse continue to ferment, supervision by platforms and government organizations is essential. The platform plays the role of a carrier of different voices, and is naturally responsible for the dissemination process of speech, and reasonably censors and restricts individual voices. It is also a mixture of social and economic interests. So it has a complex influence. If it is not managed properly, it may have the opposite effect.

It is undeniable that social media is not only an intermediary for content dissemination, but also bears the responsibility of governance in terms of content review. The vague definition of its identity leads users to attach special emotions to it. On the one hand, individuals adhere to the right to freedom of speech when creating content, while some of the users’ speech sometimes conflicts with the platform’s regulations. This leads to the platform often facing accusations of violating user rights when combating hate speech.

On the other hand, the platform’s content review standards are usually not public. It is also constantly adjusted according to new practices. The content posted by users will be deleted or even at risk of being blocked. They will find the platform’s practices incomprehensible and intensify the spread of inappropriate speech, thus creating a bad social atmosphere.

As Flew (2021) explained, online platforms face huge challenges between free expression and protecting users from harmful content. In particular, when hate speech spreads rapidly, it not only incites violence, but also encourages discrimination and prejudice. It is also important to note that in the context of inconsistent regulatory standards around the world, different legal provisions and cultural customs will deepen the difficulty of platforms in coordinating public interests.

Perpetrator or Victim? Individual Identity is Ambiguous

“The internet is like a mirror: it reflects who we are, not who we pretend to be.”

In cyberspace, individuals can post information anonymously. People may attack a person or a group of people because of emotional out-of-control and group effects, which can cause great harm to the Internet ecology and the parties involved. Platforms should indeed provide users with the freedom to express their opinions, but this freedom can evolve into extreme hate speech and violent behavior in the case of regulatory errors. Individual prejudices or personal grudges spread in social networks, leading events to completely different outcomes like a butterfly effect.

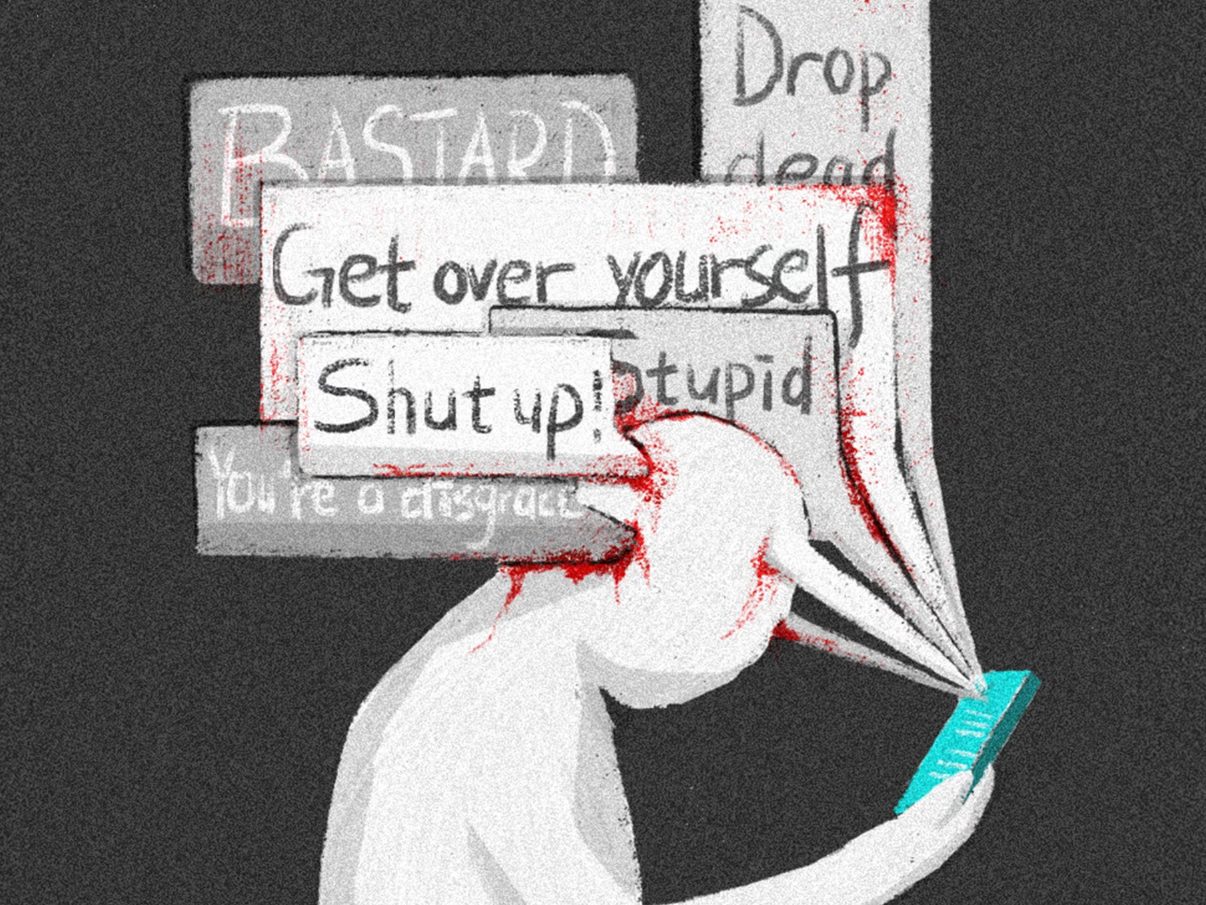

In recent years, a serious incident of online abuse has occurred in China. In July 2022, Zheng Linghua, a 23-year-old Hangzhou girl, shared a photo of herself with her grandfather on a hospital bed with pink hair on social media. She used it to celebrate her admission letter to graduate school. However, netizens misinterpreted and maliciously commented on her hair color, saying that her hair was “improper” and even spread rumors that she had an improper relationship with her grandfather. In the end, Zheng Linghua committed suicide on January 23, 2023 because she could not bear the continuous cyber attacks. During the period, she also tried to collect evidence and seek legal and media assistance to save herself, but the effect was minimal.

In April 2024, a Chinese netizen “Fat Cat” chose to commit suicide because of emotional problems. People ignored the psychological fragility of “Fat Cat” and blamed his girlfriend for the tragedy. As a result, his girlfriend became a victim of online abuse, suffered large-scale malicious comments, human flesh searches, and rumor spread, and could not live a normal life. This incident reflects that netizens can lose control due to herd mentality and emotional catharsis. Then they commit online abuse against strangers.

These two incidents have caused adverse social impacts and reflect the social prejudice against women’s appearance and behavior. Just because of the hair color, an innocent girl’s life was destroyed. And netizens turned sympathy into endless abuse of his girlfriend. There are countless irresponsible individuals who have fueled the flames behind these seemingly absurd incidents. It is important for platforms to regulate speech, but if netizens do not restrain themselves, they may become murderers who push innocent people into the abyss. On the contrary, when dealing with the huge amount of online information, people learn to speak cautiously and be more tolerant and understanding. The tragedy may not happen at all.

Individuals can be both perpetrators and victims of violence. Some individuals use their right to freedom of speech to make offensive remarks. Such groups eventually become the leaders of online abuse, which has a negative impact on society. They ignore the truth of the matter and just treat others as victims of their emotions. The lack of self-discipline and moral sense exposes the risks brought by the platform allowing anonymous and rapid dissemination of information.

I believe that reducing the phenomenon of online abuse requires individuals to be responsible for their own behavior. Individuals should improve their media literacy and emotional management skills and treat online information rationally. At the same time, do not blindly follow the opinions of others and cultivate the ability to think independently and distinguish right from wrong.

Censorship or Protection? The Platform Dilemma

Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have gradually become the core of social communication. In a 2021 report jointly released by the University of Sydney and the University of Queensland, researchers evaluated Facebook’s strategies and effectiveness in dealing with hate speech in the Asia-Pacific region, focusing on how the platform faces the region’s unique language, culture and political context. The study found that Facebook has inconsistent regulations for different countries in terms of content review standards and enforcement. Among them, the Asia-Pacific region has weaker supervision. Moreover, differences in language and cultural understanding have led to the phenomenon of platforms accidentally deleting or missing hate speech. These investigations make us wonder: Who should define hate speech? Are platforms really doing a good job in content review?

In the digital media age, hate speech-related incidents on platforms are emerging in an endless stream. In February 2025, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) arrested and charged a 41-year-old Victorian man. He was charged with sending multiple death threats and anti-Semitic insults to a federal member of parliament through social media. The police seized relevant electronic devices as evidence. The man took advantage of the anonymity of social media to contact members of Congress many times and attack them with anti-Semitism. The lack of regulation on the platform has made it a hotbed for the spread of hate speech.

In addition, the Myanmar military government has created about 700 fake accounts and pages on Facebook since 2013 to spread false information and hate speech against the Rohingya ethnic group. Its purpose is to provoke ethnic and religious tensions and create public opinion support for violent actions against the Rohingya ethnic group. Rohingya refugees filed a $150 billion lawsuit against Facebook in 2021, accusing it of failing to prevent hate speech against them. As the main social media platform in Myanmar, Facebook’s algorithm inadvertently amplified the spread of hate speech and failed to take effective measures to curb the spread of content in time.

As for online abuse, the platform definition also needs to be improved. In March 2025, Canadian anti-transgender activist Chris Elston posted a tweet on X (formerly known as Twitter) targeting an Australian transgender man, using the wrong gender name and mockery. The Australian Electronic Safety Commissioner determined that the tweet violated the Online Safety Act and required the X platform to delete the content. X platform blocked the tweet in Australia, but plans to appeal the order with Elston, arguing that it involves issues of freedom of speech. This incident shows that it is difficult for platforms to find a balance between excessive censorship and the proliferation of harmful content. Freedom of speech does not mean condoning sexism and online abuse. In addition, the platform should protect the privacy of victims and prevent secondary harm.

We can see from these cases that there is still a enormous space for platforms to explore the identity of “censors”. Platform structure sometimes facilitates the spread of harmful content. Matamoros-Fernández (2017) proposed the concept of “platformed racism” by analyzing the social media dissemination process of a racial dispute in Australia. That is, the structural design of social platforms (such as algorithms and recommendation mechanisms) may amplify racist speech. Digital platforms are not neutral media, but participate in the process of content reorganization. Therefore, platforms need to optimize their algorithms and constantly reflect on whether their own structures are creating problems.

At the same time, platforms should get rid of direct harm caused by cultural bias. Carlson and Frazer (2018) found in their study of Aboriginal online identity and the phenomenon of “social media mobs” that platform governance lacks protection for Aboriginal communities and misunderstands their cultural context. “Social media mobs” undermine Aboriginal users’ enthusiasm for participating in online speech by humiliating and harassing them. This shows that social platforms lack cultural sensitivity, resulting in the failure of review systems and governance.

Harmony or Hatred? Co-Creation of Individual and Platform

The spread of hate speech and online abuse is never the result of a single party. They are constantly amplified by the synergy of individuals and platforms, causing serious damage to the network ecology. Under the platform algorithm, users’ offensive speeches are pushed to a wide audience, triggering a chain reaction. Similar comments gathered together form a destructive force.

We can see from individual examples that malicious comments from individual users can form an emotional vortex. The incentives of social platform algorithms make harmful content like, comment and forward, resulting in collective public opinion dissemination. In the process of content dissemination, the platform did not guide the speech to develop in a rational direction timely. The inefficient platform supervision has evolved into tacit approval of violent speech, allowing irrational individuals to vent hatred and anger even more.

Hate speech is not only the product of extreme individual behavior, but also affected by the platform’s review standards, technology and structure. Due to the shortcomings of social platform review standards such as lack of openness and transparency, complexity and difficulty in understanding, and lack of uniformity in the international context, ordinary users cannot understand the formulation of rules in many cases. This in turn makes individuals dissatisfied and difficult to judge whether their behavior is illegal. Some netizens with insufficient cultural literacy or personality defects even take pleasure in challenging the legal boundaries of the platform.

Faced with many difficulties in the online environment, we should realize that the boundaries between individuals and platforms are not clear. Both individuals and platforms should bear responsibility for the adverse effects of hate speech and online abuse. Individuals should improve their awareness of civilized expression and tolerate various cultural phenomena. Platforms should obtain user feedback timely and adjust content output. While ensuring freedom of speech, improve regulatory efficiency, avoid the subjectivity of manual review, improve system algorithms, and formulate mature review policies.

Conclusion

To effectively control hate speech and online abuse, the efforts of individuals, platforms and governments are indispensable. Individuals should respect others, improve their empathy and reflect on their own speech. Platforms should assume social responsibility, improve their algorithmic mechanisms, and find a balance between freedom and control. From now on, we should strengthen the public’s media literacy education, promote cooperation and co-governance between platforms and governments, and jointly maintain public space. Behind the keyboard is not a lawless place. Individuals’ online voices should be based on platform rules and create a healthy online environment.

Reference

Australian Federal Police. (2025, February 7). Victorian man charged after allegedly making death threats and antisemitic comments against federal MP. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/feb/07/victorian-man-charged-after-allegedly-making-death-threats-and-antisemitic-comments-against-federal-mp-ntwnfb

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2018). Social Media Mob: Being Indigenous Online. Macquarie University. https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/social-media-mob-being-indigenous-online

China Daily. (2023, February 21). Death of pink-haired woman underlines threat from cyberbullying. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202302/21/WS63f47e6ba31057c47ebb000e.html

CCTV News. (2024, June 30). “Fat Cat” case triggers cyberbullying: Ex-girlfriend Tan targeted by large-scale online attacks. CCTV News. https://news.cctv.com/2024/06/30/ARTImBPMXIntbPD9b1gt6j3s240630.shtml

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In Regulating platforms (pp. 91–96). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta‐analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137.

Li, X., & Ding, X. (2024, May 20). Her boyfriend killed himself. The internet blamed her. Sixth Tone. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1015186/her-boyfriend-killed-himself.-the-internet-blamed-her.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021, July 5). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Final report to Facebook under the auspices of its Content Policy Research on Social Media Platforms Award. Department of Media and Communication, University of Sydney and School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland.

The Paper. (2023, April 8). Pink-haired girl subjected to cyberbullying: How the media reported it — A recap of the incident. The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_22614224

The Guardian. (2025, March 31). Anti-trans activist tests Australian regulator’s power to remove X post it deemed cyber abuse. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/mar/31/anti-trans-activist-tests-australian-regulator-power-to-remove-x-post-it-deemed-cyber-abuse-ntwnfb

Be the first to comment