Do We Really Know What We’re Agreeing To?

” I’ve read the privacy policy.” Sound familiar? Most of us scroll straight to the “Agree” button just to use an app faster. TikTok, the app you’ve probably spent hours watching, knows more about you than you might think. But have you ever asked what it does with that information?

Digital platforms often hide serious data practices behind long, unreadable privacy documents. While we think we’re giving permission, we might actually be giving up control. This blog post argues that TikTok’s idea of “consent” hides deeper power structures. The platform’s default settings quietly take our personal data and use it in ways we never truly agreed to. In doing so, TikTok represents a larger issue: how big tech companies are shaping the rules of digital privacy without asking real questions — or giving us real choices. Terms of service documents aren’t designed to be governing documents; they’re designed to protect the company’s legal interests (Suzor, 2019).

Saying Yes Doesn’t Always Mean You Meant To

We often assume that by clicking “Agree,” we’re making a real choice. But in many cases, including with TikTok, that sense of choice is just an illusion. Digital privacy isn’t only about whether we give consent—it’s about whether that consent is informed, genuine, and appropriate for the situation. When apps bury details in lengthy terms or rely on default settings, our so-called choices are shaped for us in subtle but powerful ways.

TikTok is a prime example. Social media platforms belong to the companies that create them, and they have almost absolute power over how they are run (Suzor, 2019). The app’s design and policies make it easy for users to share data without realizing it. As Helen Nissenbaum (2015) explains in her theory of “contextual integrity,” privacy is violated when personal information is taken out of the context in which it was originally shared and used for unrelated purposes—like targeted ads or facial recognition. This mismatch between expectation and reality lies at the heart of today’s digital privacy problem.

TikTok’s Consent System: Is It Really Transparent?

Let’s be honest: how many of us have actually read TikTok’s privacy policy? It’s long, full of legal jargon, and written in a way that discourages deep understanding. Most users skip it entirely, tapping “Agree” just to get to the fun part — watching videos. But behind that simple tap, TikTok is quietly collecting a surprising amount of data.

TikTok tracks your location, the device you’re using, how long you watch a video, what you swipe past, and even your facial features and voice. Some of this information is collected even if you’re not logged in. For example, TikTok uses device “fingerprinting” techniques to identify users based on their device settings, hardware, and software — meaning even if you don’t sign up, you’re still being watched. As Karppinen (2017) observes, today’s digital media environment is increasingly shaped by the “structural power” of a few dominant tech platforms whose algorithms determine what we see, what we do, and how our personal data is used.

It’s not just about what data is taken, but how that data is reused. A user might think they’re just watching short videos for entertainment, but TikTok may turn that activity into a detailed behavioral profile to train algorithms or sell targeted ads. These new uses are often completely unrelated to the original reason the data was shared.

This is where Helen Nissenbaum’s theory of contextual integrity becomes essential. According to her, privacy is violated when personal information is taken out of its original context and used in different ways. When you post or scroll through TikTok videos, the context is leisure and connection. But TikTok shifts that context — using the same data for advertising, predictive analytics, or even AI development. That’s not just a technical process — it’s a breach of trust. So, is TikTok being transparent? Not really. It gives the illusion of consent, while quietly repurposing your data in ways that most users wouldn’t expect or approve of if they truly understood what was happening.

Who Owns Your Data?

A major global concern about TikTok is where user data goes once it’s collected. The U.S. and European Union have raised serious questions about TikTok’s ties to China and whether the company transfers user data to servers where it could potentially be accessed by Chinese authorities. Given China’s national security laws, which may require companies to cooperate with the government, this issue raises fears over surveillance and misuse of personal information. TikTok’s global operations highlight what Karppinen (2017) calls a deeper concern in digital governance: “who has the authority and the ability to govern, and in response to what goals?” The answer, currently, is rarely the user.

This issue brings us to an increasingly important concept: data sovereignty. This refers to the principle that personal data should be governed and protected by the laws of the country where the user resides. However, when apps like TikTok operate across borders, your data might be stored or processed in countries with less transparent or weaker privacy protections.

According to the U.S. Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights, users should “expect that companies will collect, use, and disclose personal data in ways that are consistent with the context in which they provide the data” (Flew, 2021). TikTok’s practices of collecting behavioral data for advertising or AI training clearly violate this expectation. This concern over TikTok’s data handling practices reached a peak in 2024. The U.S. government passed a law requiring TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, to sell the app within a year or face a nationwide ban. This move followed years of scrutiny, including executive orders, congressional hearings, and restrictions on government employees using the app. The driving fear? That TikTok could be used by the Chinese government to access American user data or influence public opinion. Here, data sovereignty is seen through the lens of national security.

To respond, TikTok rolled out “Project Texas,” a plan to store U.S. user data on servers located in the U.S. and monitored by domestic firms. Though this plan aims to build trust, critics argue that technical measures don’t resolve deeper concerns about who ultimately controls the company and the data.

Across European countries, regulatory approaches have developed along distinct pathways when handling technology matters. Unlike strategies focused primarily on security concerns, European data protection frameworks place greater emphasis on safeguarding personal information and individual rights. Under comprehensive data protection regulations known as GDPR, organizations must comply with strict requirements governing how user information gets collected, stored, and transferred between regions. During recent years, European oversight bodies initiated multiple examinations regarding potential cross-border data flows involving TikTok, particularly examining whether European user information might be accessible in other jurisdictions. The Irish data authority proposed substantial financial penalties after identifying instances where engineers located outside Europe could access user data, which contradicted established privacy rules. Other nations implemented similar measures – France issued fines related to cookie consent mechanisms while Italy requested detailed explanations about data accessibility by foreign entities.

In addressing these concerns, TikTok introduced a strategic initiative involving localized data management solutions. This involved constructing new storage facilities within European borders and collaborating with regional cybersecurity experts to review data handling processes. While demonstrating compliance efforts, these measures also highlight increasing governmental demands for technology platforms to align operations with local regulatory expectations. Countries are drawing boundaries around data, and TikTok is the latest battleground.In today’s digital world, where your data goes can say a lot about who really controls your rights.

Not Everyone Has the Same Choices

Marwick and boyd (2018) call this problem “networked privacy.” It means your privacy isn’t just about what you do, but also about what people around you do. For instance, you might be careful not to overshare online, but if your friend tags you in a TikTok without asking, your data and image are out there anyway.

The platform’s content recommendation mechanisms, similar to many automated systems, tend to prioritize certain material that amplifies existing societal patterns or generates high engagement. This situation creates particular challenges for minority groups and underrepresented communities. For example, female users from Asian backgrounds might find themselves repeatedly shown beauty-related content reinforcing traditional stereotypes, whereas creators from African descent frequently observe reduced visibility for their contributions.

Two interconnected issues emerge from this reality. First, individuals with limited societal influence become more vulnerable to systemic biases within automated systems. Second, these same groups often lack adequate resources to effectively address such challenges, whether through technical tools, advocacy channels, or public platforms for raising concerns.

Therefore, when discussing digital privacy protections and information rights, it becomes clear that equal conditions don’t exist across different user groups. Creating fairer online environments requires explicit recognition that those most impacted by data practices typically possess the least capacity to influence change. Put simply, meaningful progress demands addressing these imbalances through inclusive policy-making and transparent system design that considers varied user experiences.

Platform Power and the Illusion of Control

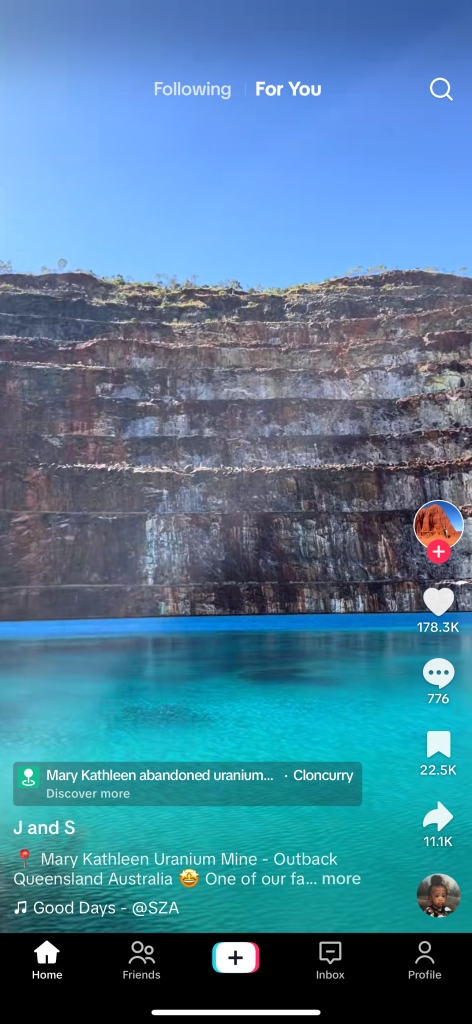

In situations where data collection and automated user categorization occur, it is often the users themselves who hold the least ability to oppose these processes. Platforms like TikTok present interfaces that appear simple and entertaining, yet behind this easy-to-use design lies mechanisms focused on capturing sustained attention—and consequently, personal information. This brings into play manipulative design tactics, that is to say, interface choices that encourage decisions users might not make under normal circumstances, such as permitting expanded data sharing or overlooking privacy customization options. Once user information enters TikTok’s systems, it fuels recommendation algorithms that directly influence content visibility. While the “For You Page” creates an illusion of personal understanding by displaying content matching perceived interests or humor, this effect stems not from genuine user empathy but from calculated measures of user interaction. The platform’s primary goal revolves around prolonging screen time through continuous scrolling and sharing behaviors rather than authentic personalization.

More concerning still, these systems frequently reinforce societal stereotypes through their categorization methods. TikTok’s labeling and recommendation approaches often simplify users into basic demographic groupings—race, gender, physical characteristics, or assumed preferences. To put it simply, these categorizations carry inherent biases. Young Asian women might find themselves directed toward beauty tutorials or passive role scenarios, while Black male users see dance content prioritized over educational or political material. What appears as customized content curation often represents predefined platform assumptions encoded into recommendation logic.

Ultimately, social platforms wield far greater influence than their public narratives suggest. Though marketed as spaces for creative expression, their fundamental operational model follows a data harvesting principle—collecting behavioral information, shaping user habits through algorithmic suggestions, and monetizing engagement metrics while maintaining the illusion of user control.

What Can We Do About It?

Addressing such complex systems requires multi-level interventions involving user awareness campaigns, regulatory adjustments, and corporate responsibility initiatives. First, improving transparency remains critical—platforms should visually demonstrate data collection practices in accessible formats rather than hiding explanations within legal documentation. Imagine interface elements showing real-time tracking of what user information gets collected and its intended usage purposes.

Second, implementing strict data protection laws becomes necessary. Some European countries already enforce regulations requiring explicit consent for data usage and corporate accountability measures. Other regions including Australia should adopt comparable frameworks governing international platforms operating within their jurisdictions, ensuring consistent standards for data handling procedures across geographic boundaries.

Third, we need better digital education. People should learn from an early age that privacy isn’t just a setting — it’s a right. Knowing how to protect your data should be as basic as knowing how to write an email or spot a scam.

Ultimately, the responsibility shouldn’t fall on individuals alone. It’s time to shift the conversation: from asking users to navigate a maze of terms and settings, to demanding that platforms and policymakers design systems that respect our rights by default. Instead of blaming people for not reading the fine print, we should ask: why is the fine print so hard to understand in the first place?

The next time you click “I Agree” on an app like TikTok, pause and ask yourself — is this really your choice, or just the easiest option designed by someone else? “We think we are making choices in our own space, but in reality, we are operating under rules written by someone else (Suzor, 2019). Real privacy isn’t just something platforms let us have. It’s a right we should expect by default — clear, fair, and grounded in trust. If our digital world is built on invisible agreements and complex settings, then it’s not just users who need to change — it’s the platforms and policies too. Because in the end, privacy isn’t a preference. It’s power. And it’s time we claimed it. Privacy shouldn’t be a luxury for the tech-savvy or the rich for the tech-savvy or the rich. It should be a basic right for everyone. And it’s time we made sure the system works that way.

Reference:

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 72–79). Polity.

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting Context to Protect Privacy: Why Meaning Matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

MARWICK, A. E., & BOYD, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1157–1165.

Be the first to comment