Image is from BBC News

Introduction

“Rashomon”, a short story written in 1915 by Japanese author Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, presents a murder mystery through four conflicting perspectives. Who is lying? What position does each narrator represent? As the search for truth becomes increasingly elusive, the setting of the story has subtly shifted—from a crumbling gate in Kyoto to the vast, chaotic arena of the digital age. And we, once mere readers of fiction, have become the very people caught in the fog of truth: the users of the internet.

In December 2019, when an unprecedented pandemic swept through every corner of our lives, the screen in front of you likely revealed a multitude of contrasting narratives:

· Official media maintained a calm and restrained tone, even going so far as to dismiss early reports of a viral outbreak in the name of social stability.

· Independent journalists issued warnings, trying to amplify the firsthand experiences of those directly affected.

· Social platforms were flooded with emotional, unverified short videos spreading panic and rumors disguised as “on-the-ground” footage

· In private chat groups and friend circles, some rushed to debunk misinformation, while others proclaimed it was the end of the world.

When major public crises strike, they often unleash a massive wave of digital information—a modern-day Rashomon playing out in real time. As physicist John Archibald Wheeler once famously said, “It from bit”—our world is fundamentally built from bits of information. We cannot exist outside of the media through which information flows, and the digital age only accelerates this entanglement. The question remains: in the flood of conflicting data, fake news, and misinformation, is your sense of reality truly your own—or is it shaped by forces you can’t even see?

How Misinformation Affects Our Lives

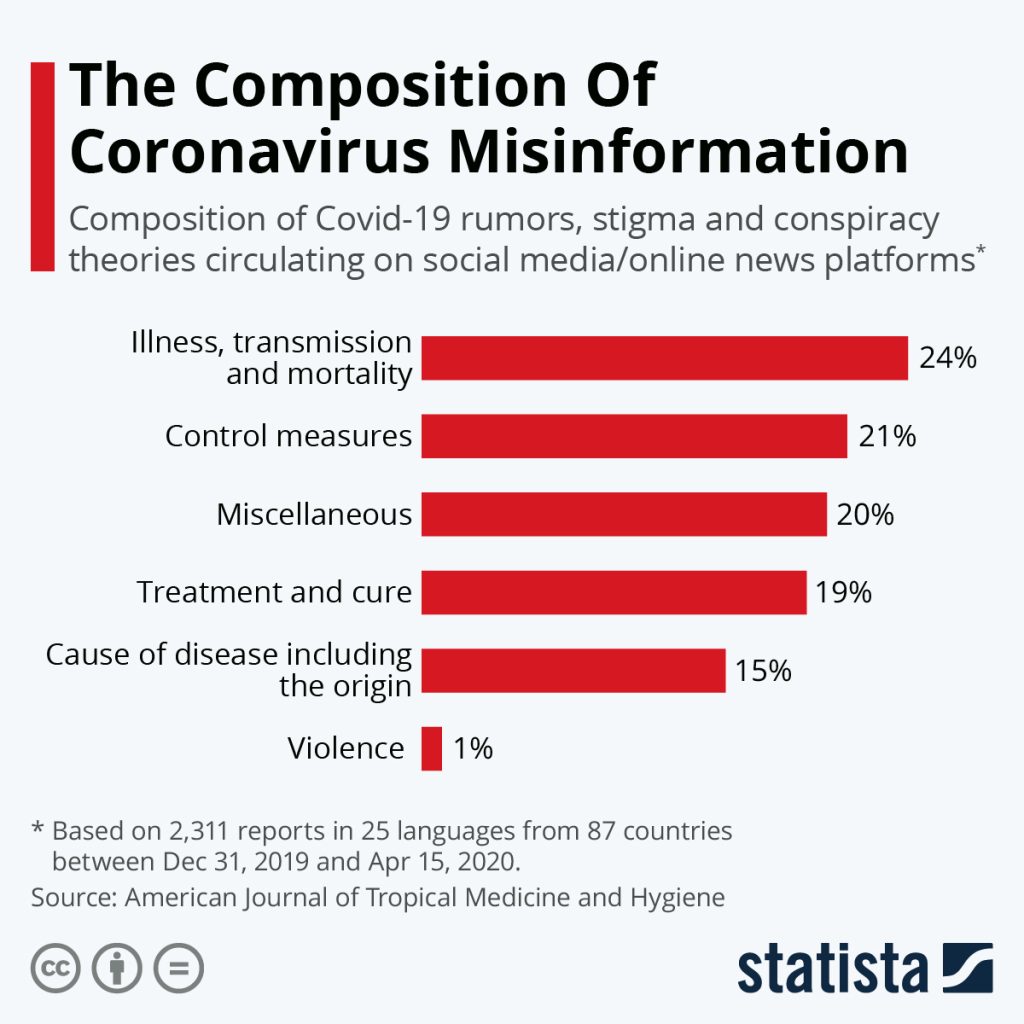

During the pandemic, it became clear that information often spreads faster than the virus itself. Claims such as “vaccines cause infertility,” “Bill Gates is implanting microchips through vaccines,” “Lianhua Qingwen cures all illnesses,” and “drinking cow urine can prevent infection” may sound absurd—but in the midst of a global health crisis, these narratives influenced the beliefs and behaviors of millions.

In the United States, many women chose not to get vaccinated out of fear it would affect their fertility. Conspiracy theories involving Bill Gates led some to reject the COVID-19 vaccine entirely. In China, Lianhua Qingwen capsules were sold out after being labeled as a COVID preventative. In India, some people even resorted to drinking cow urine in the belief that it could prevent infection. These pieces of misinformation led people away from science, delayed timely treatment, wasted social resources, and in some cases, threatened patients’ health and lives.

Source:Statista – “The Composition Of Coronavirus Misinformation” https://www.statista.com/chart/22527/composition-of-covid-19-misinformation/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Beyond public health, the spread of misinformation online can also fuel cyberbullying and hate speech. In China, the widely publicized “Fat Cat suicide case” sparked national outrage when online rumors claimed the man had died by suicide due to psychological abuse from his girlfriend. Angry netizens doxxed and attacked the woman in a campaign of online revenge. However, a police investigation later revealed that it was actually Fat Cat’s sister who had deliberately spread misleading information online to manipulate public opinion against the girlfriend. A personal tragedy was thus twisted into mass hysteria, escalating into widespread online gender antagonism. Some malicious posts even exploited the situation to promote misogynistic narratives.

Most disturbingly, even after the police report attempted to clear the girlfriend’s name, a portion of the public continued to vilify her—choosing to ignore the official facts and instead cling to their initial beliefs. This phenomenon exemplifies what psychologists call confirmation bias—the human tendency to prioritize information that aligns with one’s preexisting beliefs (Livingston, S. & Bennett, W. L., 2020).

Why Is Fake News So Popular?

According to a 2018 study published in Science by MIT researchers Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, false news spreads six times faster than true news. But what makes fake news so appealing and widespread? 10.1126/science.aap9559

In the book Regulating Platforms, several factors are identified as contributors to the rampant circulation of misinformation:

1. The Internet Has Lowered the Entry Barriers to the Media Industry

Unlike the era of traditional media—where a journalist typically had to pursue a university degree in journalism and work for an established newspaper or television station—today’s digital information landscape is marked by decentralization and fragmentation. Now, anyone can start a “news” career by creating a social media account and branding it “XX News.” As the volume of information increases, the quality and credibility of that information become harder to verify.

Many individuals who participate in the creation and dissemination of misinformation do so for economic gain. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, teenagers in Macedonia developed hundreds of pro-Trump, anti-Hillary fake news websites—not because they were politically motivated, but because the advertising revenue was lucrative.

Source: BuzzFeed News – How Macedonia Became a Global Hub for Pro-Trump Misinformation

2. More People Are Relying on Social Media for News

According to a 2024 report by the Pew Research Center, over half of U.S. adults (54%) get news at least occasionally from social media platforms. Media scholar Terry Flew (2021) argues that this trend partially stems from a growing distrust in traditional media.

This erosion of trust has been building for years. A 2016 Gallup poll conducted during the U.S. presidential election found that public confidence in mainstream media had dropped to a record low of 32%. In China, following the deadly Urumqi fire on November 24, 2022, the silence from state-run media outlets triggered widespread public anger. Citizens were forced to turn to independent blogs and social platforms to piece together what had happened.

[Source: foreignpolicy.com]

When traditional media is no longer perceived as a credible authority, the public turns to a broader, more diverse range of information sources—however unreliable they may be.

3. The Nature and Mechanics of Social Media Platforms

Social media platforms are designed to encourage rapid information diffusion through features like likes, shares, and comments. False news is often more dramatic, emotional, or sensational—making it more “shareable.” Algorithms are programmed to prioritize engagement, so they push content that is trending, controversial, or emotionally charged, often without regard to its source credibility.

Additionally, the rules governing what content gets amplified are determined by the platforms themselves, not legal standards. Users have little power when disputing content decisions, as the platform holds the ultimate authority. In this environment, misinformation thrives.

But why do people still enthusiastically share unverified content?

Terry Flew (2021) suggests that for many individuals, consuming news isn’t just about seeking truth—it’s also about seeking identity affirmation. For example, when a food delivery worker sees a post criticizing exploitative delivery platform policies, they are more likely to engage emotionally and share the content before verifying its accuracy. In these moments, the need to express frustration and assert group identity can outweigh the desire for factual precision.

AI Is Rewriting History Through Misinformation

On April 2, 2015, a popular film critic on Weibo with over two million followers, Projectionist of Theater No. 3, published a post titled “I Survived an Online Attack.” In it, he described the cyberbullying he faced after criticizing a TV drama featuring a prominent celebrity. But what truly terrified her wasn’t just the wave of online abuse—it was what happened afterward.

The Weibo profile page of Projectionist of Theater No. 3. Image sourced from Weibo.

When he later searched his name on the AI chatbot DeepSeek, she discovered that the AI had synthesized online rumors and malicious misinterpretations of his original post into a seemingly objective but deeply inaccurate summary of his actions and words. In his post, he wrote:

“The rise of AI has given me a new fear of cyberbullying. AI has become a bulletin board of history. Its ‘objectivity’ unintentionally turns rumors into historical records—blurry, unerasable, and dangerously misleading. In the age of AI, a single individual’s innocence is now the smallest unit of history.”

In recent years, multiple research reports have warned that advancements in artificial intelligence are exacerbating the spread of misinformation and fake news.

One academic paper published in the ACM Digital Library pointed out that large language models like ChatGPT and DeepSeek can generate massive amounts of text that mimic human writing. These tools can be weaponized to produce persuasive fake information, posing a significant risk to information-heavy platforms and applications. ACM Digital Library

In February 2025, Reuters reported on a UK study which found that AI-generated fake news could even trigger financial crises. According to the research, generative AI is capable of creating false stories about the safety of banks, causing mass panic withdrawals and threatening economic stability. Reuters

“A lie told a thousand times becomes the truth.”

——Joseph Goebbels

Ancient Chinese wisdom echoes a similar sentiment through the idiom “If three people repeat a lie, it starts to sound like the truth,” warning that repeated hearsay can create false realities.

Today, AI can aggregate and reframe massive amounts of content with incredible speed—creating a powerful platform for telling stories and shaping narratives. The problem lies in the asymmetry between how easily people receive information and how difficult it is to verify it. In this imbalance, AI becomes a dangerous accomplice in spreading falsehoods, amplifying disinformation with a veneer of credibility.

Political Propaganda and the Global Information War

Have you seen headlines about Donald Trump vowing to “go after the media” if he returns to power? The Guardian once referred to the Trump era as a “transformational moment for the media”—a time of reckoning that tested the very foundations of democracy. When mainstream media narratives begin to lose objectivity, public trust in democratic ideals begins to erode, and a collective anxiety over truth and manipulation takes root.

The headline about Trump on the homepage of The Guardian, image sourced from The Guardian.

According to Livingston and Bennett (2020), the crisis of legitimacy faced by authoritative institutions is at the core of today’s chaotic information landscape. When politicians weaponize the media for electoral gain—distorting facts and using selective reporting to attack their opponents—information ceases to serve the public good. It becomes a tool of power. In such a world, media no longer holds power accountable; instead, it attempts to shape public opinion. And that takes us one step further away from true democracy.

Have you also noticed the rhetorical battles between Western and Eastern media outlets—accusing, distorting, manipulating—each side vying to control the ideological narrative? It is not merely reporting anymore; it is a global contest for influence, disguised as journalism.

“Disinformation is the world’s most powerful weapon. It travels at the speed of light and costs almost nothing.”

——Richard Stengel

Perhaps disinformation can yield short-term ideological victories. But the consequences of those lies—social division, distrust, and institutional decay—are only beginning to unfold. Regardless of the country, people in any democracy deserve to know the truth about the world they live in. After all, no one likes being kept in the dark.

The Role of the Public in the Turbulent Information Age

In a chaotic jungle of mixed truths and falsehoods, what role should we—the ordinary members of the public—play?

“To be misunderstood is the fate of the speaker; to avoid misinterpretation is the responsibility of the listener.” ——Projectionist of Theater No. 3

In the face of today’s overwhelming and often contradictory digital world, we must develop the ability to discern fact from fiction—and the patience to wait for the full picture to emerge. We should refrain from attacking others online before the truth is clear, and above all, resist becoming creators or spreaders of rumors ourselves.

Reference

Flew, T., Iosifidis, P., Meese, J., & Stepnik, A. (2024). Digital platforms and the future of news: regulating publisher-platform relations in Australia and Canada. Information, Communication & Society, 27(16), 2727–2743. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2023.2291462

A Brief History of the Disinformation Age: Information Wars and the Decline of Institutional Authority. (2020). In The Disinformation Age (pp. 3–40). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108914628.001

Silverman, C. (2016, November 3). How Macedonia became a global hub for pro-Trump misinformation. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo

Pew Research Center. (2024, March 28). Social media and news fact sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

McCammond, A. (2016, September 14). Public confidence in media falls to all-time low in 2016. Politico. https://www.politico.com/blogs/on-media/2016/09/public-confidence-in-media-falls-to-all-time-low-in-2016-228168

Kuo, L. (2022, November 28). Chinese media is silent on the protests. That could backfire. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/28/china-protests-beijing-ccp-xi-jinping-urumqi/

Spitale, G., Caselli, T., & Tonelli, S. (2023). Challenging assumptions in automatic detection of misinformation: Comparing human and machine performance. Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’23). https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581318

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Zhou, J., Zhang, Y., Luo, Q., Parker, A. G., De Choudhury, M., Goyal, T., Peters, A., Mueller, S., Väänänen, K., Kristensson, P. O., Schmidt, A., Williamson, J. R., & Wilson, M. L. (2023). Synthetic Lies: Understanding AI-Generated Misinformation and Evaluating Algorithmic and Human Solutions. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581318

Stengel, R. (2019). Information Wars: How We Lost the Global Battle Against Disinformation and What We Can Do about It (1st ed.). Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated. https://sydney.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=cdi_globaltitleindex_catalog_348043421&context=PC&vid=61USYD_INST:sydney&lang=en&search_scope=MyInst_and_CI&adaptor=Primo%20Central&tab=Everything&query=any,contains,Information%20Wars:%20How%20We%20Lost%20the%20Global%20Battle%20Against%20Disinformation%20and%20What%20We%20Can%20Do%20About%20It&offset=0

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Be the first to comment