Will people still consent to information being collected when biometric surveillance becomes the norm? Australia's latest privacy reforms have opened up a debate about civil rights and digital system.

Australia’s privacy law reforms learn from facial recognition scandal and superannuation breaches

In November 2024, Australia’s Bunnings Group was accused of breaching the Privacy Act 1988 by secretly using facial recognition technology (FRT) to obtain customer information without their consent at 63 stores in New South Wales and Victoria. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has issued a ruling against Bunnings Group, determining that its practices do indeed violate the Privacy Act and requiring the group to delete all biometric data currently collected.

In April 2025, Australia’s largest superannuation funds (including AustrianSuper and Rest super) suffered a coordinated cyberattack, whose financial data breach led to the destruction of tens of thousands of members’ data, exposing the vulnerability of their data governance framework.

Together, these two cases have catalyzed comprehensive privacy law reform in Australia, demonstrating that today’s privacy framework is inadequate to address the risks posed by an data-driven society. This blog explores whether Australia’s Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024, which will come into force in 2025, will succeed in responding to security and privacy challenges and balancing the fundamental rights of citizens with digital system-driven innovation in an age of technological advancement.

Case Study: Australian Security Privacy Breach

1.Citizen Data Privacy Issues Raised by the Bunnings Group Incident (2024)

- From “security tool” to “over-surveillance”

Between 2018 and 2021, Bunnings deployed facial recognition technology (FRT) in 63 stores, ostensibly to prevent theft and violence, but actually used to collect customer information data. According to an OAIC survey, more than 500,000 customers’ biometric data was collected, and less than 0.3 percent of that was related to security incidents. This data is hidden commercially, used to track consumer traffic patterns for consumer behavioral analysis, and shared with third-party companies. The data is collected simply by posting tiny signs at store entrances, without full consumer consent and without any indication that the data will be retained and utilized for secondary purposes.Bunnings exploits a loophole in the old Privacy Act, claiming that “de-identified” biometric data is not protected by law (user names and addresses are removed). However, the OAIC shows that individuals can be easily identified by cross-referencing AI with data such as customer purchase history. This not only exposes systemic problems with Australia’s old privacy laws, but also highlights the unfavorable regulation of AI technology, which prioritizes corporate interests over those of individuals.

- Traditional “user consent” mechanisms are failing

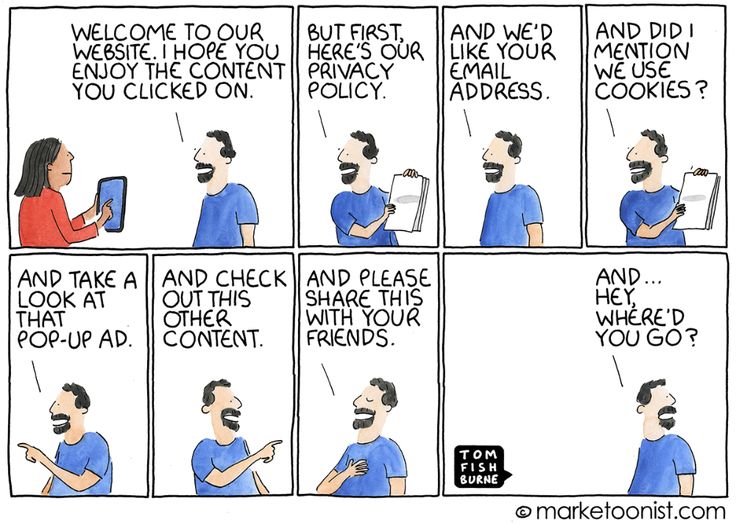

In the digital economy, “consent” is often contained in various types of complex terms that are often opaque, leaving users with the option of passively accepting such complex mechanisms.

In the Bunning Group case, most customers were unaware that facial recognition would record information about their faces, and those who were aware were faced with a mandatory dilemma: either they chose to accept the facial scan or they were required to manually enroll their personal information-ironically, the process of manual enrollment required the Ironically, the manual registration process requires the entry of more personal information.

- Helen Nissenbaum’s theory of “contextual integrity”

Nissenbaum’s theory of “Contextual Integrity“based on privacy norms provides a reasonable framework, as she argues that privacy is not whether information is “made public” but whether it is shared in “the right context” and according to “the right norms”. “In her classic article “Privacy as Contextual Integrity” (2004) and subsequent writings, Nissenbaum suggests that modern privacy invasions are not as simple as they seem. subsequent works, Nissenbaum suggests that modern privacy invasions are often not mere leaks of information, but rather “inappropriate changes” in the way information flows, i.e.:

When a person shares information in a certain context, they have specific expectations about how it will be used. If that information is used or communicated in a completely different context, it violates Contextual Integrity. For example, it is acceptable for a customer to have their face scanned at a security checkpoint, but doing so at a retail checkout violates contextual expectations and turns a protective measure into commercial surveillance.

Helen Nissenbaum

2.Cyberattack on Australian Citizens’ Superannuation Fund (2025)

- Are digital systems too fragile?

April 2025 Australian superannuation funds suffered a major cyber attack, with National Cyber Security Coordinator Michelle McGuinness saying cybercriminals targeted individual accounts holding multiple superannuation funds, with the hack compromising 600 member accounts and resulting in a loss of AUD$500,000 for four subscribers, according to The Guardian, The superannuation funds attacked included Australian Retirement Trust, AustralianSuper, Hostplus, Rest and Insignia, with Rest Super reporting that 20,000 accounts were stolen, including important personal information such as tax file numbers and investment history and other sensitive financial data.

- Limitations of corporate self-regulation

In Lawlessness, Nicholas Susol dissects the platforms’ operating model, detailing how they use terms of service to avoid self-regulatory responsibilities. According to Susol, companies use the ambiguity of the law to maximize profits, treating privacy fines as a “cost of doing business” rather than a deterrent. While a spokesperson for the Australian Superannuation Foundation said citizens can trust their cyber safeguards to retire savers and that the Australian superannuation industry is working together to improve defenses, the spate of cyberattacks reflects outdated cyberencryption protocols, lax multi-factor authentication (MFA) requirements and delayed disclosure by corporations.

- Terry Flew’s critique of self-regulation

In Digital Platform Regulation, Terry Flew suggests that self-regulation is inherently limited, that the adoption of self-regulation by firms is often accompanied by opacity, and that rules that are made by firms and are subject to final interpretation often insulate them from significant liability. For example, the Bunnings Group’s defense that the company only uses facial recognition as a “security measure” and defines FRT as a “neutral tool” avoids detailing when data is stored and to which interest groups the data is exposed. exposed to which interest groups. The case of the hacking of the Australian superannuation fund also exposes the failure of corporate self-regulation, which can lead to a growing crisis of trust among citizens when users are unaware of when their data is being recorded and processed, and when corporations fail to make it clear or even mislead them. The incidents at Bunings and the Australian Superannuation Fund have also exposed the fragility of Australia’s digital systems and raised questions among digital citizens about when companies transparently communicate risks and disclose data.

Are Australia’s privacy law reforms really enough to close the data gap?

In response to the ever-advancing digital systems and the increasing number of data incidents, and in response to the public trust, the Australian Government reformed the privacy laws at the end of 2024 by passing the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act. Key reforms include:

1.Expanding the scope of protection: inclusion of “de-identified data” in the oversight

- Highlights of the new regulation

“De-identified Data” means specific personal information that cannot be directly identified after processing. Many technologies today allow individuals to be re-identified through “de-identification” methods (e.g. by combining various pieces of data about a citizen). The Australian government therefore hopes to bring this type of “de-identified data” within the scope of privacy laws to prevent companies from abusing data on the grounds of “de-identification”.

- Case Matching

Bunnings Group: After 2025, groups will face fines of up to 10% of annual turnover if they record biometric data, even of the “de-identified” type, without the consent of the citizen (Bunnings’ fines are around A$450 million).

Australian Superannuation Fund: Encryption of personal data of foundation members, especially “de-identified” data, with strict access controls to prevent unauthorized re-identification.

2. Limiting data collection: introduction of the “Data Minimisation Principle”

- Drawing on the EU General Data Protection Regulation

The “Data Minimisation Principle” is essentially a data protection principle, meaning that businesses can only collect the minimum amount of information necessary to complete their services. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (collectively GPDR), which came into effect on May 25, 2018, is one of the most stringent data protection laws in the world, with provisions that specify that only the necessary data should be collected and not “over-exploited.” The Australian government has drawn on this principle to push for data privacy law reforms to limit the excessive collection of user data by companies and platforms.

- Case Matching

Bunnings Group: Group can use FRT for security and theft prevention, but user biometric data must be deleted immediately thereafter, and all persistent storage for “data analytics” will be penalized in violation of the law.

3. Enforce dynamic accountability and enhance data transparency

- Key Points Disclosure

Reforms to Australia’s privacy laws mean that businesses are obliged to disclose information about data usage and the logic of data analysis using AI to citizens, and that businesses must publish a summary of the language on how data processing is done to demonstrate compliance, or the OAIC will investigate and impose severe penalties.

- Case Matching

Bunnings: need to explain to citizens how FRT can be used to differentiate between shoplifters and regular shoppers or it will be assessed as excessive surveillance.

Individual rights: Consumers can now challenge the results of automated decisions and have the right to request the deletion of personal data generated by AI and ask for human review.

What exactly is undermining data security?

1. Cost concerns

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has very strict privacy protection requirements, such as the need to: appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO), conduct a high-risk Data Processing Impact Assessment (DPIA), maintain compliance documentation, and respond to user data access. Often Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) do not have a legal team, lack an IT security foundation and do not have the capacity to support the technical and human resources required for compliance. If Australia’s privacy law reforms move towards a “GDPR-level” standard without clearer guidelines or support, it could disproportionately burden smaller players and even prevent SMEs from engaging in AI-related innovations, while larger tech companies remain better resourced to comply.

2. Technical complexity

To truly detect whether a business or platform is violating privacy laws (e.g., harvesting facial information, illegally collecting user data, etc.), manual review of documents is not enough; detecting non-compliant data requires developing various types of software, learning machine models, and developing AI audits; however, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is the legal regulator, and the majority of their staff members are legal specialists rather than AI technologists or engineers. The OAIC currently lacks expertise in this area and does not have a dedicated “technical investigation team” or “algorithmic auditing team”, so it may not be in a position to verify the truth of a company’s claims of compliance.

Conclusion: Towards a brighter digital future together

Data privacy in the digital age requires targeted governance, and different strategies can be adopted to address the challenges of cost and technological complexity. Regulators can simplify compliance mechanisms for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and governments or industry can come together to create funds to subsidize them to encourage innovation. For regulators like the OAIC, upgrading the technology base is key. The government can partner with universities to develop programs such as AI detection systems and facial recognition risk assessment tools, and establish a technical group of data experts within the OAIC to improve its capabilities.

Digital systems have changed the rules of engagement between people and platforms, turning data into a commodity.The Bunnings and Australian Superannuation Fund incidents do not signal a failure of privacy and security reform in Australia, but rather a reflection of corporations prioritizing profits over citizens. Australia’s 2024 reforms to integrate privacy laws into the digital society mark a turning point, signaling progress in increased oversight of data systems, independent audits, and renewed user safeguards, with the hope that citizens and governments will consciously embrace data as a responsibility that needs to be upheld, and work together to move towards a digital future.

Reference

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2025, April 4). Australian superannuation funds hit by cyber attacks, with members losing $500,000. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-04-04/superannuation-cyber-attack-rest-afsa/105137820

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2025, April 4). At least $500,000 lost in cyber attacks on super funds [Video]. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-04-04/at-least-500-000-lost-in-cyber-attacks-on-super-funds/105140462

European Union. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Official Journal of the European Union. https://gdpr-info.eu/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge: Polity Press. (pp. 72–79)

Hoskins, G. T. (2023). Digital Platform Regulation: Global Perspectives on Internet Governance, Terry Flew and Fiona R. Martin (Eds.) (2022). Journal of Digital Media & Policy, 14(2), 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1386/jdmp_00125_5

MinterEllison. (2025, January 29). Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 now in effect. https://www.minterellison.com/articles/privacy-and-other-legislation-amendment-act-2024-now-in-effect

Nissenbaum, H. (2004). Privacy as contextual integrity. Washington Law Review, 79(1), 119–158. https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol79/iss1/10/

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting context to protect privacy: Why meaning matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0030-5

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC). (2024). Facial Recognition Technology Investigation: Bunnings Group. https://www.lavan.com.au/advice/cyber-and-data-protection/Bunnings_Facial_Recognition

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who makes the rules? In Lawless: The secret rules that govern our lives (pp. 10–24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Be the first to comment