Could you imagine that every time when you post online, chat with friends on social media, and even click will be monitored and recorded? Some might think it sounds like a conspiracy theory, but the truth is—it has happened around us before, and it’s still happening now.

In the digital age, we have access to powerful tools for communication, but also facing unprecedented means of surveillance. Since 1969, when the information was sent over the Internet for the first time, user privacy in the digital age has become a hot topic.

There’s no denying that the birth of the internet has greatly improved the efficiency of communication and access to knowledge. However, as we leave traces of ourselves online, the balance between privacy and convenience must be carefully considered.In 1998, the Pew Research Center began to survey respondents about their attitudes toward privacy on the internet, and found that 54% of respondents were concerned about the issue. Twenty years later, this number has risen to 91% (Flew, 2021).

There is one example in particular that stands out starkly as digital privacy concerns continue to grow-PRISM. This surveillance program, once hidden from the public, revealed just how deeply government agencies can reach into our private online lives.

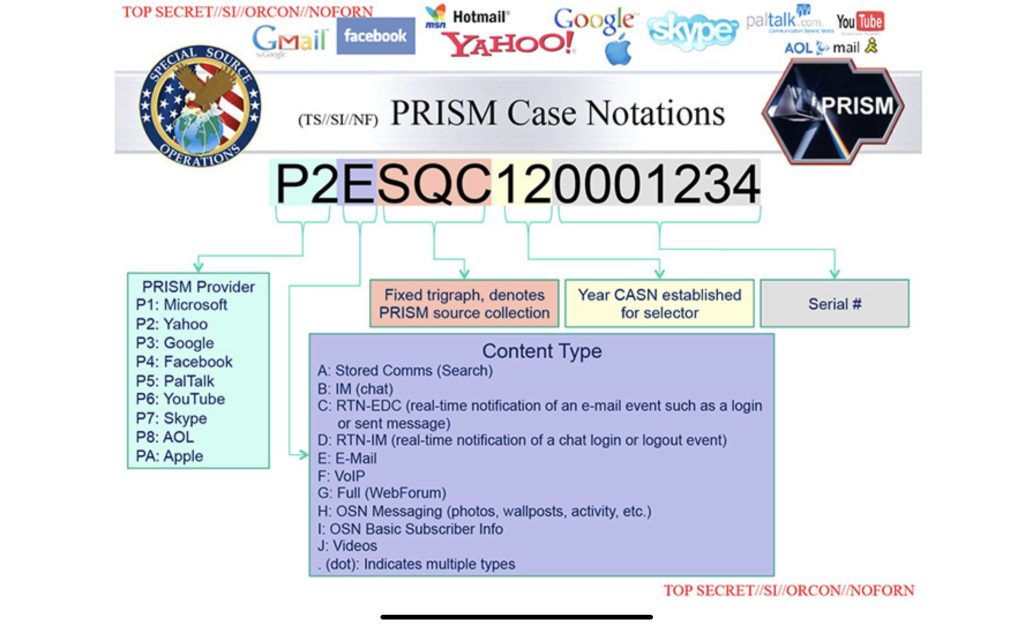

What is PRISM? PRISM is the code for the National Security Agency (NSA) program, which started in 2007 after the passage of the Protect America Act under the Bush Administration. The purpose of PRISM is to collect information on Internet communications from various US Internet companies.

How was PRISM executed? Who will execute PRISM? Through reaching an agreement with Microsoft, Yahoo, Facebook, Google, Paltalk, Youtube, Skype, Paltalk, AOL and Apple, the NSA are able to intercept the communications of the person they designate, including email, messages, etc. In actuality, the collection process is carried out by the Data Intercept Technology Unit (DITU) of the FBI.

Since digital communications data tends to take the least expensive route, and most of the world’s Internet infrastructure is located in the United States. Therefore, most of the world’s electronic communications pass through the United States, which means the NSA is able to intercept any information it wants from all around the world.

Since its official launch in 2007, PRISM was revealed publicly by an NSA contractor, Edward Snowden, by sending a series of classified documents leaked to The Washington Post and The Guardian. Through those leaked classified documents, Edward Snowden showed the operation and processes behind the PRISM program to the public, so we could know the process of how our communications on the Internet are intercepted, stolen and stored without the user’s permission.

Figure 1: The top slide of PRISM program by NSA

The exposure of PRISM represents a turning point in the global conversation around online privacy, surveillance ethics, and digital rights. After this, Internet users started to understand that while enjoying the benefits of technological advances, there are some traps that we should avoid.

There is no doubt that we should embrace technological progress. Therefore, what pitfalls do we face today? Who is responsible? How should regulatory powers be distributed? And how can we protect ourselves in the internet world?

There is no doubt that we need to rely on effective internet regulation and legal frameworks to protect ourselves. However, can the existing laws and regulations truly safeguard our rights? To this day, society still has not reached a consensus on whether the PRISM program itself violates the US Constitution. Opponents of PRISM believe that the program’s extensive information collection model infringes on free speech and the right to privacy, while supporters claim that by using the services provided by these platforms, users implicitly consent to the collection of their data. Therefore, PRISM neither violates the law nor infringes on human rights.

However, undoubtedly, PRISM is a morally flawed program since it intercepts and monitors user information without the user’s authorization. Most notably, the act of concealing this surveillance from users constitutes a serious violation of privacy, which is fundamentally a human rights issue. In addition, since this program involves a huge amount of private communication information, if this data is misused or leaked, it is likely to have very serious consequences.

In fact, the debate surrounding PRISM cleverly reflects society’s deeper concerns about internet governance and information security: Where should we draw the line on data security in an information society? Can internet users truly be aware that their actions leave behind traces and data that can be accessed by others?

When using platform services, we are usually required to register an account and agree to a user agreement, and we usually choose to agree to the terms by simply ticking the box without carefully reading the agreement. In fact, to avoid legal issues related to user data usage, these agreements are often deliberately complex, vaguely worded, or even include hidden clauses (Suzor, 2019). Most users do not carefully read each clause before confirming the agreement, and must agree to the terms in order to use the relevant services. For platforms, it means our personal data is collected, stored, and used for profiling and algorithms, which also raises serious concerns about data misuse and the risk of information leaks.

Have you ever received spam or scam calls? Have you ever wondered how these callers got your phone number — or even your name? The answer often lies in online account registrations.

Flew mentioned another case in Platforms on trial (2018): Facebook user information was leaked and sold to the team that helped Trump run for president in 2016. This incident clearly demonstrates the immense value of personal information in the digital era. In fact, since Facebook was founded, they have apologized publicly countless times for user information leaks, but none of this has prevented the next information leak event. Meanwhile, in China, a country with a 1.4 billion population, the problem of information trafficking has also become increasingly severe. In 2023, Chinese authorities arrested an individual who had sold over 10,000 pieces of citizens’ personal information, earning merely 9,000 yuan (approximately USD 1,300) from the crime (Qing, 2024).

Although compared with the interference caused by the information leakage of Facebook in the US presidential election, the implementation reason of the PRISM program seems to be more justifiable – the NSA claims that PRISM is to avoid more terrorist attacks and protect the American people – but undoubtedly, monitoring and intercepting others’ information without permission is a challenge and infringement on human rights.

From the TikTok Ban event, Facebook hearings, to Apple joining the US AI safety agreement. In recent years, more and more events have shown that governments are increasingly willing to exercise their right to regulate online supervision and information management, although many of these attempts have failed.

As well as this, the rise of fake news is another major reason why there has been such an increase in public interest in information regulation. It can be explained as follows: ‘Fake news’ is often used to refer to news or propaganda that misleads the public with false information in order to achieve political, economic, market, or psychological objectives and benefits by misleading the public with false information. Donald Trump frequently used the term “fake news” in his speeches during the 2016 U.S. presidential election to attack the news that was unfavorable to him when he was campaigning for the presidency.

The decline in public trust in the media is the most direct manifestation of this. In the current United States, the public’s trust in the media is almost based on the political leanings of the media itself. For instance, supporters of the Democratic Party do not believe in the news reports of Fox News, and supporters of the Communist Party generally do not believe in the news reported by The New York Times.

Flew (2018) argues that this is mainly because digital platforms are currently not regulated as effectively as traditional publishers and broadcasters. Existing laws already regulate the content of digital platforms to some extent. However, these laws do not provide sufficient regulation because digital platforms and the companies behind them differ from traditional media in terms of their social responsibility, profit model and purpose. Interestingly, compared with media platforms or companies, some of them still consider themselves as a technology company, which is quite ridiculous since they rely on social media and online interactions as their main source of income.

In fact, such cases of excessive regulation driven by the desire to protect corporate interests are not limited to politically sensitive topics. Suzor (2019) points out in his paper that some companies often use the excuse of protecting users from diverse cultural backgrounds to justify their content moderation policies. However, in reality, these policies tend to protect the company’s commercial interests rather than truly reflect the values of users.

Regarding the issue of network regulation, no matter what countermeasures are adopted, it is essential to first clarify that protecting human rights will be the ultimate goal of all policies and regulatory methods. On this basis, Karppinen (2017) believes that completely unrestricted free speech has been proven to be unfeasible, and Suzor (2019) also suggests that due to the influence of interests, platform regulation cannot be entirely the responsibility of the platforms themselves. Therefore, the self-regulation of enterprises, the participation of the government, the formulation of rules, the participation of relevant stakeholders, and the participation of independent third parties in the regulation are also crucial (Flew, 2018). Multi-stakeholder governance has become the best solution to this problem.

To explain, multi-stakeholder governance is a governance practice that brings together multiple stakeholders to participate in dialogue, decision-making and the implementation of responses to commonly perceived problems. This approach is typically applied to government policies, public health, internet governance, digital rights, and other related issues. The advantage of this structure is that since all relevant stakeholders can participate in decision-making and implementation, the final decision will be inclusive, transparent, and anti-monopolistic. At the same time, since decisions will be made simultaneously by multiple parties, this means that all participants will also bear corresponding responsibilities, which is conducive to accountability and multi-party cooperation. Of course, multi-stakeholder participation also implies greater investment of capital, human resources, and time, and the cycle of decision-making and implementation will also be longer, which is inconsistent with the fast-paced characteristics of the current media.

Furthermore, as Flew (2018) pointed out, it is also crucial to introduce an independent third party to supervise the formulation and management of policies. By establishing a credible third party, it will not only be easier to restore public trust in platforms, media and news, but also make the “black box” transparent and open, thereby encouraging more users to participate in the network and media.

Finally, I believe that technological progress should be a tool for humanity and bring benefits to our lives, rather than restrictions. The birth of the Internet has broken through physical restrictions for us and brought a way to observe the world across time and even space, and we haven’t been able to learn to coexist with this technology well. As a techno-optimist, I am willing to believe that with the emergence of more perfect legal and governance systems, we will coexist peacefully with this technology and observe this world in more ways.

Reference

Digital Lives (pp. 10–24). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flew, Terry (2021). Issues of Concern. Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.

Flew, T. (2018). Platforms on trial. InterMedia, 46(2), 24–29.

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge companion to media and human rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge.

National Security Agency (NSA). (n.d.). PRISM slides [PowerPoint slides]. Internet Archive.

Qing Li. (2024, April 11th). The man bought 10,000 pieces of personal information and sold them for 9,000 yuan, earning him a year in prison. The Paper.Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules? In Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern our

Be the first to comment