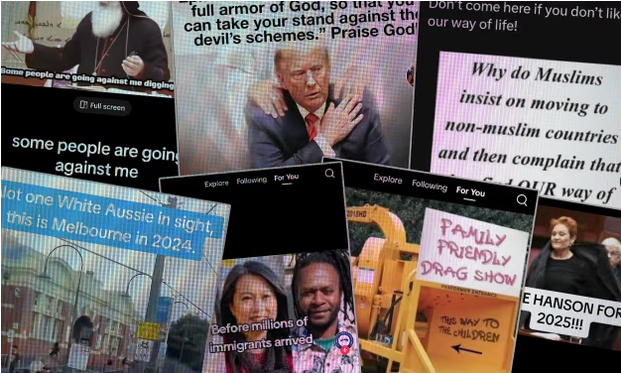

Figure 1. Example of hate and polarising content surfaced on TikTok’s For You page. Source: Josh Taylor, 2024.(https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/27/tiktoks-algorithm-is-highly-sensitive-and-could-send-you-down-a-hate-filled-rabbit-hole-before-you-know-it#img-1).

You enter TikTok anticipating simple entertainment, a trending dance, perhaps a recipe, or simply a funny clip. However, you get a few videos into your “For You” page, and the content begins to shift. Anti-immigrant messaging, hate speech in less blatant forms, and memes mocking an entire community are now appearing. You did not search for them. You did not request them.

And yet, the algorithm delivers them anyway.

Introduction

As TikTok’s global influence expands, so too does scrutiny over the algorithmic curation of content. It has over a billion users worldwide, and to some extent, this should affect the way that people—especially young people—consume information and engage with social and political issues. While the nature of its design favours user engagement and personalisation, it may often promote emotionally appealing content that drives interaction regardless of its factual accuracy or social consequences.

Recent research suggests that TikTok’s algorithm can actively and instantaneously expose users to vitriolic, misleading, and polarizing material—regardless of prior searches or viewing habits (Weimann & Masri, 2023; Meade, 2024). This raises serious questions about how TikTok’s algorithm works, and what it means to automate the delivery of content at this scale. When problematic content is served to users passively and swiftly, it raises questions about the moral obligations, not only for the platform to moderate content but the obligations to design, implement, and amplify, what they previously deemed opprobrious inappropriate or contemptuous content.

Algorithmic Priorities: Engagement Over Ethics

TikTok’s recommendation system does not just react; it is predictive and prescriptive. Many social media platforms blend personal connections and user intent, while TikTok’s “For You” feed is entirely determined by personal algorithmic impressions. The algorithm analyses even the most subtle indicators of interest—such as the time a user lingers on a video, whether they replay it, swipe past, or pause momentarily—to determine what content to serve next. Unlike a chronological or follow-based feed, TikTok’s model quickly builds a behavioural profile and then reinforces it, creating tightly curated content loops.

This loop can spiral quickly. A detailed investigation by The Wall Street Journal highlights the speed and accuracy with which TikTok’s algorithm identifies user interests. In the video How TikTok’s Algorithm Figures You Out (Wells, Horwitz, & Seetharaman, 2021), reporters set up dozens of automated bot accounts and programmed them to linger slightly longer on videos containing particular emotional themes. Within minutes, the app began feeding those accounts increasingly specific, emotionally loaded content—ranging from anxiety and loneliness to political conspiracy and misogyny. Even without explicit searches or interactions, the algorithm pushed each bot deeper into siloed content worlds.

The Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). How TikTok’s algorithm figures you out [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfczi2cI6Cs

This kind of content reinforcement has profound consequences. TikTok’s engagement-focused model prioritises content that provokes emotional intensity, regardless of whether that content is constructive, harmful, or factually accurate. As Andrejevic (2019) describes in his analysis of “automated culture,” algorithmic systems don’t simply reflect preferences—they structure attention and shape perception. What the algorithm amplifies becomes more visible, more influential, and more culturally powerful, irrespective of its ethical or societal implications.

This creates an environment where extreme, polarising, or even hateful content may outperform nuanced or factual narratives. Content that generates outrage, identity-based tribalism, or visceral reactions tends to travel further, be shared more widely, and occupy more space on the platform. In this sense, TikTok’s algorithm doesn’t just serve what users “like”—it trains them to like what it promotes.

The design is intentional. As Safiya Noble (2018) argues in her work on algorithmic oppression, digital platforms embed and reinforce systemic biases under the guise of neutrality. TikTok’s seemingly neutral algorithm is in fact shaped by its underlying commercial logic: the goal is time-on-platform, not user well-being or social cohesion. In this context, engagement becomes a poor proxy for value—and a dangerous one when it comes to content related to race, religion, or politics.

This logic lays the groundwork for what the following case study will demonstrate: hate speech, cultural division, and political propaganda don’t just appear by accident on TikTok—they flourish within the very mechanics of the system.

Case Study: When Hate Goes Viral: TikTok and the Israel-Palestine Conflict

During the escalation of the Israel–Palestine conflict in late 2023, TikTok became one of the most active platforms for real-time commentary, political mobilisation, and emotionally charged expression. While some users shared personal stories and calls for peace, the platform also saw a flood of hate-fuelled content, including antisemitic tropes, dehumanising imagery, and videos promoting extremist viewpoints. For many of these, there was not only a direct user search, but also appeared through algorithm-driven “For You” feed. Outlets such as Sky News and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) conducted investigations into this phenomena and reported that polarising and emotionally volatile videos consistently performed better in visibility and reach compared to videos that were neutral or context-rich.

Figure 2. Screenshots of TikTok videos related to both sides of the Israel–Palestine conflict, illustrating the volume and polarised nature of algorithmically recommended content. Source: Sky News, 2024 (https://news.sky.com/story/is-tiktok-the-new-battleground-for-the-israel-palestine-conflict-13035547).

This trend is indicative of a larger structural issue in how the platform operates. As Andrejevic illustrates (2019), automation on a digital platform doesn’t just distribute content, it also focuses attention on spectacle. In TikTok’s example specifically, the content that is most prone to going viral is the content that is able to generate outrage, a division based on identity, or emotional overreaction. Within this period, content was generated by both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian sides of the conflict, as shown in Figure 2 below from Sky News (2024). Even with opposing sides, both sets of content follow the same amplification logic: they demonstrate emotional content, high visual impact, and are able to be pushed by an algorithmic logic.

Furthermore, how some narratives became amplified while others (e.g., pro Palestinian or pro Israeli accounts) were shadowbanned or muted, illustrates what Noble (2018) calls algorithmic oppression. She illustrates that algorithmic systems are not neutral but code in the values and blind spots of their makers. In this context, TikTok’s amplification behaviours reflected larger political biases leading to online harassment and tensions offline. The approach TikTok took to moderating content around this topic raised concerns not just from users, but from human rights standards pressing for more transparency into the algorithmic systems used.

Figure 3. One Nation leader Pauline Hanson speaks in the Senate chamber at Parliament House in Canberra, Australia, following controversial remarks that were later deemed Islamophobic by the Federal Court. Source: Daily Sabah, 2024 (Court rules against Australian senator for anti-Muslim remarks | Daily Sabah).

Similar processes of amplification have arisen in other cases, too. Video clips about Australian right-wing characters, such as public anti-immigration and Islamophobic commentary from politicians like Pauline Hanson, have emerged as a trend on TikTok, for example. Hanson holds leadership of the One Nation party, and has a lengthy public history of inflammatory comments. Her warning, for example – “We are in danger of being swamped by Muslims” – is quite frightening. Most recently, in 2024, the Federal Court ordered Hanson to take down a social media post that breached Australian racial discrimination law for being anti-Muslim (Figure 3).

Although the content may not always be classified explicitly as hate content under platform policies, it still draws from the same algorithmic logic of engagement: emotionality and high arousal, clear & simple messages, and cultural divisiveness. She is often shared in videos of her political slogan/rallying cry and clad in nationalistic imagery and themes, often against immigration. On TikTok, the same content might quickly enter the recommendation cycle—not because users are searching for hate content—but because the content is sensational and lights a strong emotional reaction, which the algorithm rewards with visibility.

Platform Responsibility and the Limits of Algorithmic Governance

TikTok’s Content Moderation Policies and Their Limitations

Figure 4. Researchers observed a four-fold increase in misogynistic content suggested by TikTok over a five-day monitoring period, indicating the platform’s algorithmic promotion of emotionally charged and harmful material. Source: The Guardian.

Tiktok has developed community guidelines banning hate speech, extremist material, and harassment. On the face of it, these guidelines appear to be a commitment towards creating a safe and inclusive space.However, the platform’s practical enforcement of these rules has faced growing scrutiny. Much of TikTok’s moderation relies on automated systems, which are fast and scalable but often miss the nuance necessary to accurately identify context or intent.

This reliance on algorithmic moderation has led to high-profile failures. For example, a recent Guardian investigation found that social media algorithms—including TikTok’s—amplified misogynistic content significantly during political controversies, with some platforms showing a four-fold increase in such content during targeted campaigns (Townsend, 2024). This suggests not just passive tolerance, but algorithmic prioritisation of material that drives emotional response—even when harmful.

Similarly, Wired reported that TikTok has struggled to effectively detect and remove neo-Nazi and far-right extremist content, which often bypasses filters through coded language, memes, or visual cues (Tufekci, 2023). While the company claims to take proactive measures, the recurring presence of these videos—and their ability to achieve virality—raises serious concerns about moderation infrastructure.

Compounding this issue is the lack of transparency around how moderation decisions are made. Researchers and watchdog groups have consistently pointed out that TikTok’s moderation criteria, appeal processes, and training standards for human moderators remain largely opaque (Just & Latzer, 2019). Without greater visibility into the platform’s internal operations, it becomes difficult to hold it accountable for the real-world consequences of content exposure.

Algorithmic Amplification and Platform Responsibility

A central concern in the governance of digital platforms is the distinction between content moderation and content amplification. While TikTok often frames itself as a neutral intermediary, merely hosting user-generated content, its recommendation engine—most notably the “For You” feed—actively selects and amplifies what users see. This curation makes the platform more than passive: it becomes a powerful editorial force.

Numerous studies and reports have shown that TikTok’s algorithm tends to prioritise emotionally charged and sensational content, including material related to hate speech, extremism, and conspiracy theories. In an investigation by The Guardian, researchers demonstrated how quickly TikTok can “rabbit hole” users into harmful content streams—sometimes in less than an hour—simply based on how long they pause on certain videos (Meade, 2024). The study found that emotionally intense videos—including racist, misogynistic, or xenophobic messages—were disproportionately surfaced by the algorithm, regardless of the user’s intent.

This raises an urgent question of platform responsibility. As Just and Latzer (2019) argue, algorithmic governance not only filters what we see—it actively constructs reality. In this sense, TikTok’s algorithms do not just reflect user behaviour; they shape it by reinforcing specific narratives, identities, and emotional states. When these mechanisms amplify harmful content, the platform bears responsibility not just for what it allows, but for what it promotes.

Adding to the concern is the opaque nature of TikTok’s algorithmic operations. Independent researchers and policy analysts have consistently called for greater transparency in how content is recommended or downranked (Weimann & Masri, 2023). Without clear disclosure of the logic behind algorithmic curation, users remain unaware of how their feeds are shaped—and regulators struggle to hold platforms accountable.

While TikTok has implemented features like “reset your For You feed” and expanded moderation teams, critics argue these are reactive solutions. What’s missing is structural reform: a willingness to scrutinise and redesign the recommendation logic itself. Until then, algorithmic amplification will continue to undermine the platform’s content policies, posing systemic challenges to digital governance.

Conclusion

TikTok is not just a platform where content happens to go viral.It is a space that has been generated algorithmically and exists where visibility is shaped, magnified, and ultimately determined through the logic of the system. While the company encourages guidelines for community engagement that say they work against hate speech and harmful content, algorithmically, it often works against its stated goal (in so far as it encourages what provokes rather than what informs).

As this blog has demonstrated, the platform’s engagement-based model isn’t just reflecting user preferences—it’s manufacturing them. In real-world situations like the war in Israel-Palestine, we saw rapid increases in extreme stories, reframed anew for local audiences, including the cultivation of anti-immigration narratives in Australia. In other words, TikTok’s recommendation engine demonstrates a disconcerting disposition: what is emotionally provocative almost always rises to the top, which has no regard for the social ramifications.

Additionally, the platform’s existing moderation procedures and transparency measures are also inadequate. Disabling or eliminating harmful content and resetting users’ feeds is reactive rather than preventative. Harmful patterns will continue to appear, typically at a pace that prevents moderation, unless and until there are substantive changes to how the algorithm works (for example, friction, transparency, or accountability in curation).

In the end, TikTok’s governance issue is not only a content issue, it’s an issue of power, who controls what people see, and what this means for the future of public engagement. If algorithms are becoming our new editors, then I would argue that platform accountability can no longer be optional and must be developed into the system from the very beginning.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated culture. In Automated Media (pp. 44–72). London: Routledge.

Anti-Defamation League (ADL). (2023). Antisemitic Content and Extremism on TikTok. https://www.adl.org/resources/article/tiktok-ban-feared-antisemitic-conspiracy-theories-follow

Daily Sabah. (2024, March 26). Court rules against Australian senator for anti-Muslim remarks. https://www.dailysabah.com/world/islamophobia/court-rules-against-australian-senator-for-anti-muslim-remarks

Josh Taylor. (2024, July 27). TikTok’s algorithm is highly sensitive – and could send you down a hate-filled rabbit hole before you know it. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/27/tiktoks-algorithm-is-highly-sensitive-and-could-send-you-down-a-hate-filled-rabbit-hole-before-you-know-it

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2019). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Noble, S. U. (2018). A society, searching. In Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (pp. 15–63). New York: NYU Press.

Sky News. (2024, March 26). Is TikTok the new battleground for the Israel–Palestine conflict? https://news.sky.com/story/is-tiktok-the-new-battleground-for-the-israel-palestine-conflict-13035547

The Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). How TikTok’s algorithm figures you out [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfczi2cI6Cs

Townsend, M. (2024, February 6). Social media algorithms ‘amplifying misogynistic content,’ report finds. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2024/feb/06/social-media-algorithms-amplifying-misogynistic-content

Tufekci, Z. (2023, October 12). TikTok’s war on hate speech is failing. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/tiktok-nazi-content-moderation/

Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2023). How algorithms facilitate self-radicalization: An audit of TikTok’s recommendation system. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231225547

Be the first to comment