Introduction

Have you ever experienced a topic or items that you happened to bring up while chatting with a friend appearing on the front page of the social media platforms just a few minutes later. Or have you ever received any scam calls where they can give the personal information including name, phone and passport number accurately. Also, if you want to use an app, there is always a lengthy privacy policy that must agree to and if you click reject which will be forced to exit the app, thus, most users choose to not read the privacy policy and just clicking agree to use the app. While modern society is seen to be respecting and protecting user privacy, with the spread of surveillance capitalism, users’ privacy and digital rights are gradually disappearing. The digital platforms are gradually becoming entitled to unlimited rights, especially when it comes to collecting private user data, users are always forced to accept privacy and terms of service when suing platforms which has led to privacy becoming commoditized (Flew, 2021). Therefore, this raises a deeper question: when users click agree to the privacy terms, is their data truly protected, or does it accelerate the rate at which it is leaked?

Background: Privacy is gone

“Do you remember how long it has been since you last read the privacy policy carefully? Do you choose to just click agree instead of reading the terms in most cases.”

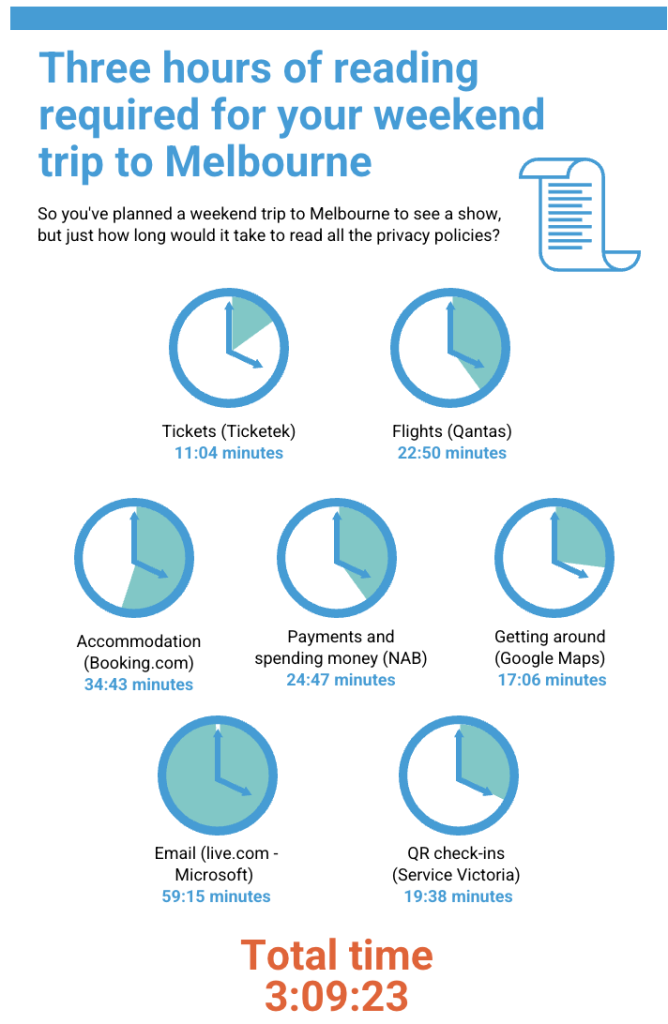

Almost all platforms now force users to accept a lengthy and confusing privacy or terms of service before they can use (Klosowski, 2023), and the users don’t know exactly what they are agreeing to, even if agreeing to the terms only enables the platform to collect users’ data. Owners of social media platforms have complete control over their networks, and the terms of service that users agree to when signing up effectively serve as the platforms’ governing documents (Suzor, 2019). Hence, the lengthy privacy terms of service can be considered elaborate by the platforms. According to research, it has pointed out that there are more than half of privacy policies are poorly readable, with the organization selecting 75 privacy clauses and finding that all averaged around 4000 words taking users around 16 minutes to read, with the longest privacy clause coming from Microsoft which took users about one hour to read (Blakkarly & Graham, 2022), it also leads to the situation of platforms controlling users, for example, users are lack of understanding and choice when agreeing to the terms (Flew, 2021).

The essence of a privacy policy is to inform users the platform or company may collect and use their data, however, some companies do not recognise and privacy protections in their privacy clauses, simply referring to these announcements as privacy clauses (Klosowski, 2023). Because of the title privacy policy, the user believes that by clicking the agree button, all of their private data will be protected, even though the fact that the company and platform are already using and sharing these data. Moreover, Flew proposes that the platform is not an intermediary, it is more like a manipulator controlling what content is visible and what information can be made public which a right that has exceeded privacy terms. We will find that when searching the web in your browser, most of them require you to accept cookies from the website and if you don’t accept this website may stop working. For example, when users create an account, they have already left a digital trail on the internet. Companies collect personal information, interests and location from the platform by using tracking cookies, even if some accounts are private, advertisers and scammers can still easily access the information (Hetler, 2024). Therefore, although many people are concerned about privacy issues in actual use they are forced to compromise with the platforms and provide personal information in exchange for access to the platforms (Flew, 2021). Privacy is disappearing, which we are losing privacy, it is exposing the fact that we are living in a social environment of surveillance capitalism.

We are now living at the age of Surveillance Capitalism

When a suer creates an account on a social media software or platforms, their digital footprints are already recorded. Are you always asked to provide personal information such as name, phone number address, etc. and the privacy terms associated with these are often difficult to understand. While these platforms and companies will alert users to the use of cookie tracking, cookies can also track and analyse users’ online activity without their knowledge, giving users the false impression: The platform is often able to recommend content that interests me (Hetler, 2024). Because viewing countless cookies and agreeing to the terms has become part of digital life, it has pointed out that platforms have simplified complex privacy terms into clickable options, however this simplicity of features and functionality is designed to impact user autonomy (100 days of Product, 2023). Thus, we already live in the age of surveillance capitalism. Surveillance capitalism is a concept created by Zuboff in 2014 which essentially refers to the use of private human experience as free material turned into data to be used on digital platforms for analysis (Laidler, 2019). Zuboff presents that people’s private data has become the last virgin land as there is very little left to commercialise (Kavenna, 2019) and she also mentions in the article that both Google and Facebook’s business models are based on acquiring and accessing users’ personal information, user data is traded in the digital marketplace and surveillance capitalists profit from it (Naughton, 2019).

Return to the ‘click to agree’ section. Nearly everyone either clicks ‘agree’ and begins using the platform and software without carefully reading the policy. Although it might appear that this clause is meant to protect user privacy, do platforms and business actually implement it? It is possible that platforms are hiding data manipulation by using complex language and reducing transparency, in other words, what you believe to be a privacy clause might not actually be one (Klosowski, 2023). While platforms provide us with choices, users have little right of refusal, as many platforms have other ways to locate people even when location information is turned off (Hetler, 2024).

Consequently, platforms now control both the distribution and dissemination of content, while also holding users’ private data. With the aid of AI, some massive platforms with extremely strong privacy regulations have also created complexity and confusion, limited user choice, the potential for random changes to policy and conditions without users’ knowledge, and an unrestricted collection of personal data. Google, Facebook and Amazon can be considered digital giants in the western country, which their control over user data is extremely strong and has less competitors (Srnicek, 2017). These digital platforms’ surveillance capabilities have expanded quickly, and the public has been powerless to stop it, which has resulted in data misuse and privacy invasion.

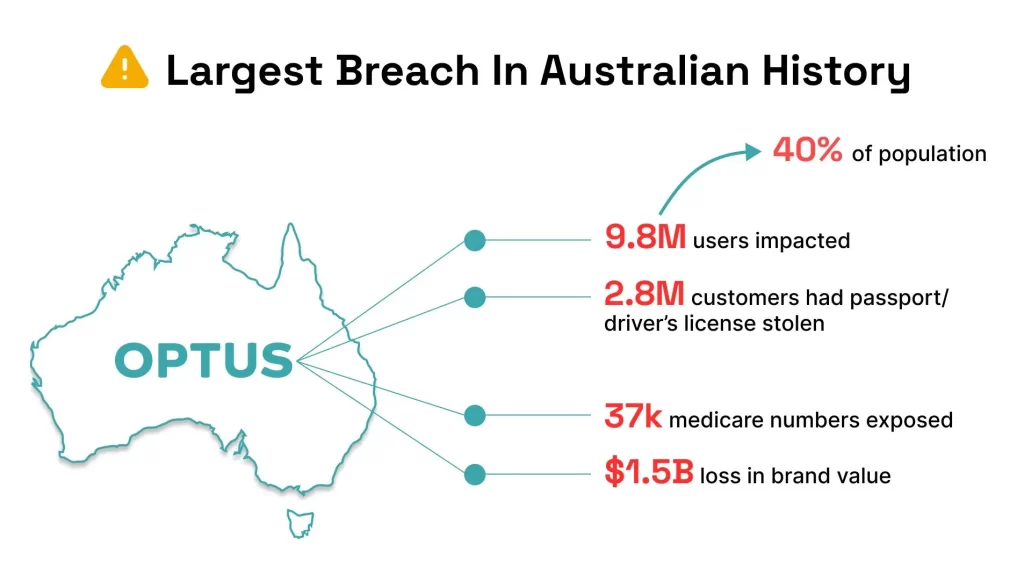

Case Study: Optus data breach & Google deceptive location tracking

In September 2022, Optus, the Australia’s second largest telecommunications company, suffered a data breach that exposed the personal information of nearly 10 million Australians (Vincent, 2024) including passport, driving licenses and medical cards. Each customer was required to consent to the sharing of their personal information for authentication purposes which Optus claimed was required by the company in order to learn more about the customers. What makes it suspicious is that Optus keeps users’ personal information for up to 6 years after collecting it to verify their identity, which Optus still claim is required by law (Ratnatunga, n.d.). While the Optus data breach was ultimately characterized as an act of negligence by an anonymous API and a code error, it has demonstrated that privacy clauses are meaningless if the company doesn’t protect users’ privacy data (Vincent, 2024). It also exposes a flaw in Australia’s privacy laws, where Optus retains data after a user cancels a contract. Australia’s privacy laws only require data retention to be destroyed when the information is no longer needed for its intended use or disclosure, but there is no specific time limit on the length it should actually be retained (Ratnatunge, n.d.). The Optus data breach has been extremely costly for victims, with basic information on almost all users compromised, and the home addresses of at 3.1 million people. it has also prompted the need for the Australian government to strengthen reforms to the Privacy Act and increase fines (Ikeda, 2024). Hence, the Optus incident reveals that users may still suffer a privacy breach even if they accept a privacy policy which has supported Flew’s (2021) statements that the current legal and regulatory environment is highly complicated when it comes to handling privacy data breaches. Users are typically required to share personal information when using the platforms, in addition to the fact that companies or platforms have limitations in terms of self-regulation, and the issue of data breaches has not been fully addressed by GDPR or Privacy Act.

Consider it in the context of your personal experience, have you ever experienced having location access turned off, but some social media platforms are still able to accurately tweet posts within your immediate area? Or you may turn off the location history, but still found that your data was leaked on social media platforms? This is known as some tech giants continue to collect and store users’ location information even if they turned off their location permissions (Bhuiyan, 2023). Google is embroiled in such a scandal. Google users are required to agree to Google’s various terms and conditions before use. According to the research, Google offers users the option to turn off location history, but Google continues to collect, use and store their personal location information through the ‘Web and App Activity’ (ACCC, 2021) mode even the users have turn off, and these settings are enabled by default. Google continues to collect and use users’ personal information even when users explicitly turn off location data and collects it through other modes on top of turning it off, which Google does not clearly specify this information in its privacy policy (ACCC, 2021), and the settings interface and language purposefully try to give the impression that users chose to opt out of tracking. In addition, Google has since been fined 93 million for misleading users for the ongoing collection of their location information, and it will also be required to agree to new policy, such as increasing the transparency of location tracking and informing users when a specific location is being used (Bhuiyan, 2023). Therefore, Suzor presented that platform operators have complete control is supported by the case of Google’s location scandal, which highlights the danger of digital platforms’ privacy clauses that permit platforms to control users’ data even they have the right to refuse. The users’ Agree button does not completely protect the privacy.

What we as users can do to protect our privacy

The issue of data leaks and fake privacy terms has become the most serious social problem in recent society, and these leaks are likely to get worse as AI technology becomes more complex. For instance, there were about 3000 data breaches in the United States in 2024, and a cybercrime group said that they stole the personal information of nearly 500 million people on the Ticketmaster website (Alexis, 2025). These data breaches have led to a decrease in trust in the services of digital platforms by users all over the world, so what can we do to maximise the protection of our private data? First of all, try to refuse to accept platforms’ requests to collect data, especially location information, for example, with iPhone, the user can ask the app not to track activity (Klosowski, 2023). Secondly, it is important to think deeply before signing up for a new account as every platform carries certain risks, and to ensure that personal information is deleted when logging out of the platform (Hetler, 2024). Furthermore, some simple actions to ensure the security of our information include:

Using strong passwords,

Trying not to use public networks,

Disabling location history data,

Avoiding providing unnecessary personal information (Hetler, 2024).

In addition, a system of government intervention or improved laws and regulations is the most direct and efficient way to protect user privacy, and more harmonisation is needed in the laws governing personal data (Lo, 2020).

Conclusion

In conclusion, many people have experienced agreeing to a platform’s privacy terms only to find that their personal information is still being leaked out by the platform or company, or even that the collection and dissemination of a user’s personal information which has led to data becoming commoditized. Platforms and companies have the absolute right to control users’ personal information which has led to a decrease in users’ trust. Clicking agree is not considered consent, and privacy clauses may be purely for show, hence, better laws and regulations are required to prevent data leakage, and simply turning off permissions is insufficient to protect user data.

Reference List

ACCC. (2021). Google misled consumers about the collection and use of location data. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/google-misled-consumers-about-the-collection-and-use-of-location-data

Alexis, A. (2025). Data privacy fears erode consumer trust in digital services. CFO DIVE. https://www.cfodive.com/news/data-privacy-fears-erode-consumer-trust-in-digital-services/742764/

Bhuiyan, J. (2023). Google to pay $93m in the settlement over deceptive location tracking. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/sep/14/google-location-tracking-data-settlement

Blakkarly, J., Graham, D. (2022). Privacy policy comparison reveals half have poor readability. CHOICE. https://www.choice.com.au/consumers-and-data/protecting-your-data/data-laws-and-regulation/articles/privacy-policy-comparison

Flew, Terry. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.

Hetler, A. (2024). 7 common social media privacy issues. TechTarget. https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/6-common-social-media-privacy-issues

Ikeda, S. (2024). Australian Austerities Trace Optus Data Breach to Access Control Coding Error, May Seek Hundreds of Millions in Penalties. CPO Magazine. https://www.cpomagazine.com/cyber-security/australian-authorities-trace-optus-data-breach-to-access-control-coding-error-may-seek-hundreds-of-millions-in-penalties/

Kavenna, J. (2019). Shoshana Zuboff: ‘Surveillance capitalism is an assault on human autonomy’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/04/shoshana-zuboff-surveillance-capitalism-assault-human-automomy-digital-privacy

Klosowski, T. (2023). Here’s What You’re Actually Agreeing to When You Accept a Privacy Policy. Wirecutter. https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/blog/what-are-privacy-policies/

Laidler, J. (2019). High tech is watching you. The Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/03/harvard-professor-says-surveillance-capitalism-is-undermining-democracy/

Lo, D. (2020). Should you know (or care) how your data is being used before you consent? UNSW Newsroom. https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2020/08/should-you-know–or-care–how-your-data-is-being-used-before-you

Naughton, J. (2019). ‘The goal is to automate us’: welcome to the age of surveillance capitalism. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jan/20/shoshana-zuboff-age-of-surveillance-capitalism-google-facebook

Ratnatunge, J. (n.d.). Optus Data Hack: The Dark Side of Invading Social Media Privacy. Certified Management Accountants. https://ontarget.cmaaustralia.edu.au/optus-data-hack-the-dark-side-of-invading-social-media-privacy/

Srnicek, N. (2017). We need to nationalize Google, Facebook and Amazon. Here’s why. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/aug/30/nationalise-google-facebook-amazon-data-monopoly-platform-public-interest

Suzor, Nicolas, P. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.

UNTV News and Rescue. (2022). Google faces lawsuits over deceptive location-tracking practices. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VhGTfSYi2Q

Vincent. (2024). How did the Optus data breach happen and how to avoid it? Corbado. https://www.corbado.com/blog/optus-data-breach

100 Days of Product. (2023). Personal Data in the Digital Ecosystem: A UX Designer’s Reflection on Control and Privacy. Medium. https://medium.com/@oliveren/personal-data-in-the-digital-ecosystem-a-ux-designers-reflection-on-control-and-privacy-91b5f5df5fd0

Be the first to comment