Sometimes, just need a seemingly ‘not brain’ comment, and you can wake up after a sleep between thousands of people ‘onlookers judgment’. Your avatar, ID, past comments, and even traces of real life have become the target of the network ‘messenger of justice’. This is not a fictional plot, this is a lot of people really experience the Internet daily.

In an era where everyone can make their voices heard, justice is no longer exclusive to the law, and has become a ‘public carnival’. Some people feel that they are doing justice, but some people are forced to withdraw from the network in this carnival, suffering from anxiety, and even to the end of life.

Why is the ‘fire of justice’ on the Internet burning more and more fiercely? What are we participating in and what are we sacrificing?

Why does online violence erupt so quickly?

On the surface, it seems that we are just ‘seeing injustice’, but why is it that when someone says something wrong, the Internet seems to explode? Why do thousands of people flock to the Internet at every turn, launching curses, exposing themselves to the Internet, and even conducting ‘human flesh searches’?

A. Everyone’s ‘sense of justice’ can easily be incited.

We all want to do the ‘right thing’ and ‘do justice’.

When a ‘seemingly outrageous’ person or event appears on the internet, the first reaction is anger and impulse, rather than thinking about whether it is true or not, and whether it has any context.

B. Platforms like content that is ‘controversial’.

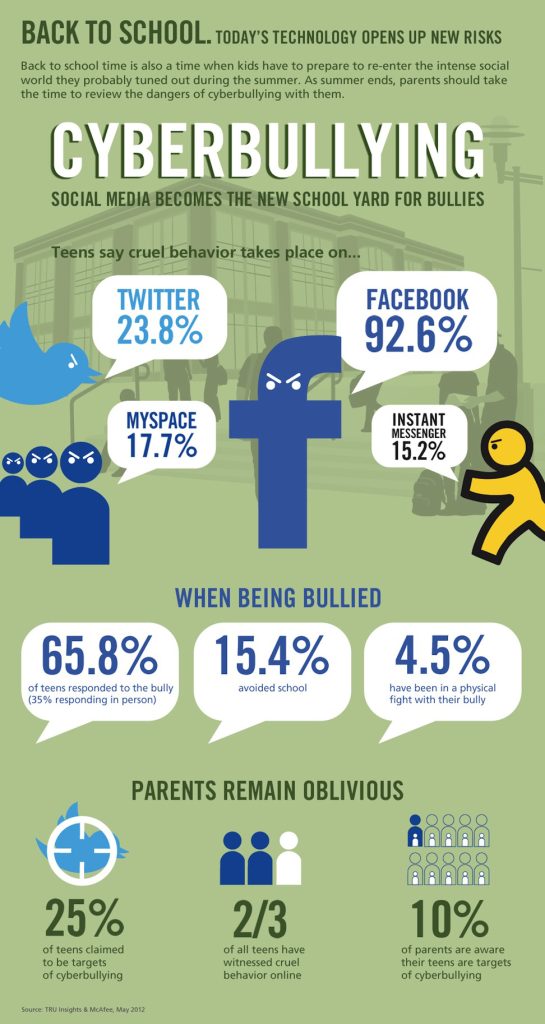

The algorithms of platforms like Weibo, Tik Tok, and X prioritize ‘controversial content’ because:

- Anger and controversy attract more clicks, comments, and retweets.

- The more noise a platform has, the more data it has, the more ads it can sell.

So the more you curse, the more it pushes, the more it pushes, the more people curse – online violence is thus ‘fed’ by the platform.

Academically, this is called the ‘emotional propagation mechanism’: emotional content spreads much faster than rational content, especially anger, fear, and humiliation.

C. Anonymity makes people ‘more courageous’.

Online, people don’t show their faces or names, and the cost is extremely low:

- You will not be held accountable immediately for cursing.

- Delete the account, change the vest and you can continue to curse.

- The group scolding will not be named.

So, many people usually in reality may be gentle and swallowed, the Internet has become a ‘messenger of justice’ or ‘network fighter’.

This is called ‘de-individualization’ in psychology – people in the group will lose self-consciousness, more likely to make extreme behaviors.

D. Cyber violence has turned into a sense of ‘participation’.

Nowadays, many people post comments and retweets not only to express their opinions, but also to ‘participate in a popular event’, ‘keep up with the heat’, or even ‘show that I stand on the moral high ground’. For example, some people have been criticized for being ‘a hot topic’ and ‘keeping up with the heat’.

You’ll find that many people are not trying to actually change anything, but rather are using ‘bashing’ as a way to show their stance. This is essentially consuming other people’s meltdowns to fulfill their own emotions.

Cyber violence is rampant not because people are bad, but because platforms, algorithms, anonymity, and group mentality have amplified ‘anger’ to a dangerous level. Everyone thinks they are doing justice, but they are probably hurting the innocent out of control.

The platform mechanism contributes: anger is more likely to ‘hit the headline’ than the truth.

Platforms are not neutral. They actually ‘amplify emotions’.

Platform algorithms ‘favor’ content that is emotionally charged and controversial, especially angry, abusive, and antagonistic. This is because such content generates a higher interaction rate (likes, retweets, comments), which is the key to the platform’s profitability.

‘Affective bias’ of platform algorithms

According to academic studies (e.g., Papacharissi, 2015; Gillespie, 2018), platforms’ recommendation mechanisms are not neutral technological tools, but are biased.

They are biased to push:

- Content that makes people’s emotions run high (anger > rationality)

- Content that triggers user behavior (retweets, comments, bounties)

- Content that is antagonistic (provokes group conflict)

Twitter, for example, has been exposed as having an algorithm that tends to amplify ‘right-wing anger’ more than the users themselves, and YouTube’s recommendation system often pushes users towards extreme content (Radicalization spiral).

The fire of online violence often comes from users, but platforms provide the wind, firewood, and oxygen.

Once the fire of justice becomes a ‘high-traffic event’, it becomes a tool for the platform to make money, and no longer the justice itself.

Users think they are administering justice, but in fact they are providing the platform with emotional data and interaction indicators.

Emotions, especially anger, are the platform’s most valuable resource. Under such a mechanism, online justice has long been not a contest of ‘right and wrong’, but a traffic show directed by algorithms and performed by anger. We thought we were speaking out, but in fact we have just become part of the platform game.

As Matamoros-Fernández (2017) points out, platform algorithms tend to favor content with ‘high emotional value’, which makes it easier for controversy and attacks to gain traffic, while rationality and explanations are often drowned in the flood of information.

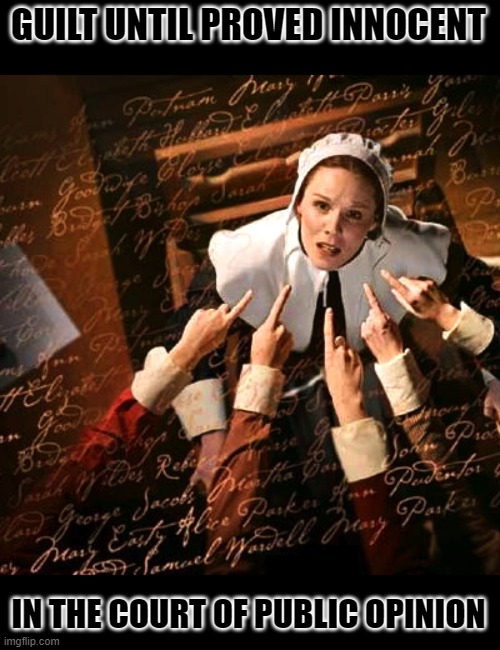

How does a sense of communal justice turn into a ‘digital witch hunt’?

Network justice may start with good intentions, but once it becomes a ‘group action’, it can easily get out of control, go astray, and become a ‘digital witch hunt’.

In this atmosphere, people are no longer pursuing the ‘truth’, but the ‘sense of punishment’, ‘emotional release’, and ‘stand in line ceremony’.

A. What is a ‘digital witch hunt’? It’s not just an Internet buzzword.

You may have come across the term ‘digital witch hunt’ on the Internet.

It may sound like an Internet buzzword, but there’s actually a lot of history behind it.

The term ‘witch hunt’ first came from medieval Europe – a time when many women were accused of ‘witchcraft’.

At the time, many women were accused of being ‘witches’, saying they were conspiring with the devil, casting spells, and harming society.

These accusations were often unsubstantiated, based on rumor, prejudice, or even ridiculous reasons such as ‘she’s too special looking’.

Ultimately, these women are dragged into the square and burned or executed in full view of the public.

This is not justice, it is collective persecution by fear, power, and prejudice.

Today, although we no longer literally ‘burn witches’, the logic of the witch hunt is still alive and well on the Internet.

If a word is said incorrectly or a video is edited and misrepresented, thousands of people will immediately rush up to ‘crusade’, exposing their privacy, scolding them to the point of withdrawing from the Internet, and even forcing them to have a nervous breakdown.

This is a ‘digital witch hunt’:

- No legal procedures

- No evidence requirements

- Only moral emotions and group anger

And you and I every click, retweet, and comment, maybe in this ‘public execution’ added a fire.

The scariest thing about ‘witch hunts’ is that they appear to be about justice – but they are essentially about punishment and exclusion. On platforms such as Reddit, gender-specific groups (especially women) are often the primary targets of digital violence. As Massanari (2017) reveals, Reddit’s cultural and algorithmic structure inadvertently encourages this ‘woman-hunting’ collective harassment.

B. Analysis of group psychological mechanisms:

a. Moral Superiority

People like to prove that ‘I am more moral than you’ by ‘accusing others’, especially on public platforms, it is easier to ‘show justice’ to brush the sense of existence.

For example, if you retweet a post about internet violence and add ‘people like her deserve to die’, you not only express your position but also get a sense of satisfaction that you’re on the side of justice.

b. Sense of belonging

Group attacks will make people feel I’m not alone in the fight, as if they are ‘people’s army of justice’ a member of the emotional hostage but also feel meaningful, and have a sense of participation.

This is like following the trend of ‘cursing’ in a social way.

c. Social punishment pleasure (schadenfreude)

Some people have psychological pleasure in ‘other people’s bad luck’, especially celebrities, the rich, and the privileged ‘collapse’, which will stimulate ordinary people in the heart of repressed emotions.

You online scolding them, in fact, is an opportunity to release their own dissatisfaction with the reality of a kind of ‘safe venting’.

The Real Cost of Cyber Violence

Cyber violence is not something that can be solved by saying ‘just don’t read the comments’.

Its effects on people are all-encompassing, deep, and even irreversible. Real life, mental health, relationships, and professional futures can all be destroyed.

See step by step how it destroys a person:

a. Loss of control

When you’re being called out all over the internet, the biggest fear isn’t ‘someone hates me’, it’s: ‘I can no longer control how others define me, and I can’t even defend myself’.

Some victims say that the most painful thing is not the cyber violence itself, but seeing ‘countless versions of me’ being reconstructed, consumed, and flirted with on the Internet, while they can’t do anything about it.

b. Destruction of social relationships

Many victims are not only attacked online but isolated in reality:

- Friends are afraid to contact her (for fear of being implicated)

- Colleagues begin to distance themselves (fear of risk to the company).

- Schools and organizations are forced to ‘stop the relationship’.

Even after clarification, others may have already labeled them: ‘They seem to have some problems’.

c. Psychological and physical trauma

People who are cyber-violated often experience:

- Anxiety, insomnia, bulimia or anorexia

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

- Depression, and even self-harm or suicidal tendencies

Studies have shown that people who have been cyber-attacked for a long period of time are as traumatized as if they had been violently attacked in real life, and some may even develop an intense fear of being ‘online’.

d. Career and life trajectory permanently altered

Especially for ordinary people (non-public figures), it is very difficult to turn around once ‘something goes wrong’.

They don’t dare to use social media anymore and even change their identity.

Some people even leave the country, change their names, and go off the grid.

The most heartbreaking thing is that after many people are ‘wrongly killed’, there is no public apology and no one is responsible.

As Roberts (2019) points out, content moderation systems are often an ‘afterthought’, making it difficult to stop the spread of online violence in a timely manner. The opaque mechanisms and commercialization priorities of platforms leave little control over the ‘fires of justice’ once they have been ignited.

Cyber violence is not a ‘conflict of opinion’ or a ‘righteous denunciation’, but a total invasion and suppression of other people’s lives. We always think that we are just expressing our positions and opinions, but the victims may have already walked into the darkest corners in real life.

In this era of the Internet, where everyone can speak out and participate in ‘justice discussions’ at any time, we often think we are doing the right thing – exposing problems, denouncing wrongs, and defending fairness. However, too often, those in the name of ‘justice’ siege, in fact, is just another form of violence.

The reason why digital witch hunts are rampant is not because we are evil, but because we are too easily ignited by emotions and wrapped up in collective anger. When thousands of people are in front of the keyboard shouting ‘justice’, who will still care about whether an ordinary person was injured by mistake?

The Internet is a public space, but it is also a public responsibility.

Freedom of expression is never an excuse to hurt others.

If justice is lost, it is no longer justice, but the beginning of disaster.

Perhaps, what we need is not more ‘voice’, but more restraint and wait.

Before pressing ‘send’, ask yourself: is this really justice, or an emotional carnival?

Reference:

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media (pp. 33–72). Yale University Press.

Be the first to comment