Social media platforms provide the space for us to connect and communicate with each other, and they set the rules for participation. –Nicolas P. Suzor

In the digital age, cyberspace has become a private space that hosts personal information, communications and family life. Privacy is a human right, as stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 12 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” According to Nissenbaum’s(2018) principle of respect for context, Internet users, as consumers, have the right to allow companies to use the law in the manner expected of them. According to Nissenbaum’s principle of respect for context, Internet users, as consumers, have the right to have their personal data lawfully collected and used by companies in the manner expected of them. But with the rise of digital technology, the growth of data and the rise of surveillance have made privacy in platformised environments a huge concern. “The most notable examples are the requirement to provide personal information as a condition of access to various online products and services, and the capacity of content aggregators such as search engines and social media platforms to onsell these data to third parties”(Flew, 2021, p. 77). Imagine that the social platform homepage is my community. I am free to decorate my home, create my favourite community atmosphere, and even carry out activities in my home and invite my friends to join. However, during my stay, I find that my home is being monitored by the community and is constantly scanning and backing up my belongings at home, even my important files and private documents that I keep in my safe. This is the state of the digital platform today.

Digital platforms: Master of Digital Information

The legal reality is that social media platforms belong to the companies that create them, and they have almost absolute power over how they are run. — Nicolas P. Suzor

The internet platform was originally established as a platform for freedom of expression.John Perry Barlow “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (Flew ,2021) asserted that through the internet “we are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. being coerced into silence or conformity.” We spend a lot of time every day on platforms like Youtube, Tiktok, X. But little attention is paid to privacy breaches and the platforms’ ability to take advantage of them. But very little attention is paid to privacy breaches and the platforms that profit from them. It is a common problem, such as credit card leakage and theft, personal information being used for non-personal purposes, and the security risks posed by geo-location data collected by platforms (Goggin et al.,2017).

What’s the biggest problem? Digital platforms face a privacy imbalance with their users. Platforms have created private ecosystems with terms and conditions documents that are not necessarily legally rigorous and are set up to make profit. There is an information mismatch between platforms and users, and platforms can take advantage of the rules of the terms of service to infringe on the interests of users. The platforms themselves set the rules (Suzor, 2019, p. 11), “They reserve absolute discretion to the operators of the platform to make and enforce the rules as they see fit.” The lack of accountability and transparency in the management of user data makes it impossible not only to trace the source but also to accurately locate the leaker in the event of a data breach. Social media platforms hide the process of content vetting and enforcement of curation to maintain neutrality, and the platforms operate in a “black box”governance (Suzor, 2019, p. 16). So once personal data is uploaded to an electronic platform, the user loses control over the personal data. The rules and judgements are controlled by the platform.

Figure1:News of The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal

source:Cadwalladr, C.& Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 18). Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election#:~:text=The%20data%20was%20collected%20through,in%20the%20US%20presidential%20election.

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal occurred in 2018, when Christopher Wylie revealed that Cambridge Analytica had collected unauthorized Facebook personal information on millions of US voters to predict the personal characteristics of US voters and target political advertisements. “Sometimes, the bias in moderation is a visible and deliberate policy choice by the platform” (Suzor, 2019, p. 18). The rapid growth of large tech companies has outpaced the response of governing bodies. If it were not for Christopher’s whistleblowing, the outcome of this case would not have come out so smoothly on a platform that is solely controlled by tech companies. A statement from Facebook reveals that the company discovered the information leak in 2015. However, instead of alerting users, Facebook took limited data recovery and protection measures privately. Everything was done before the regulatory bodies reacted, and it is clear that it is difficult for regulatory bodies to effectively enforce the law on this. Such a regulatory imbalance means that the platform holds all the power.

Government management: still working on it

The right to privacy has been taken to be an inherent human right, albeit one that is qualified in practice by other competing rights, duties, and norms. – Terry Flew

When government regulatory agencies struggle to enforce mid-stream, try to get to the root of the problem.2024 On 10 September, the Hon Anthony Albanese MP, Prime Minister, announced that the Australian Government would introduce the Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Bill 2024, mandating 16 as the applicable age for social media, transferring responsibility for protecting minors to the platforms.

The Bill will amend the Online Safety Act 2021 (the Act) to:

– Require age‐restricted social media platforms to take reasonable steps to prevent Australians under

16 years old from having accounts (the minimum age obligation),

– Introduce a new definition for ‘age‐restricted social media platform’ to which the minimum age obligation applies, alongside rule‐making powers for the Minister for Communications to narrow or further target the definition,

– Provide for the delayed effect of the minimum age obligation of no later than 12 months after Royal Assent,

– Specify that no Australian will be compelled to use government identification (including Digital ID) for age assurance purposes, and platforms must offer reasonable alternatives to users,

– Establish robust privacy protections, placing limitations on the use of information collected by platforms for the purposes of satisfying the minimum age obligation, and requiring the destruction of information following its use,

– Provide powers to the eSafety Commissioner and Information Commissioner to seek information relevant to monitoring compliance, and issue and publish notices regarding non‐compliance,

– Impose maximum penalties of up to 150,000 penalty units (currently equivalent to $49.5 million) for a breach of the minimum age obligation by corporate actors,

– Increase maximum penalties of up to 150,000 penalty units for corporate actors for breaches of industry codes and standards, to reflect the seriousness of the contravention, consistent with community expectations, and

– Incorporate a range of other minor measures and consequential amendments to give effect to this.

Video1:Online Safety Amendment Social Media Minimum Age Bill 2024 Second Reading

Source:Jenny Ware MP. (2025, January 07). Online Safety Amendment Social Media Minimum Age Bill 2024 Second Reading[Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYf_x4NYaZQ

MP Jenny ware spoke at the second reading, this is a ban, but a ban must be implemented when the dangers of the ban are far less than the dangers posed by the banned activity. The purpose of this ban is to keep all minors safe from the internet. It also gives parents the right to stop minors from using the internet excessively.

The difficulty in enforcing the bill is that it gives the power of enforcement to tech companies. As previously analysed, companies often consider profit over legality and compliance.TikTok and YouTube have both been penalised for violating children’s privacy.Sherman (2024) notes that TikTok, one of the world’s most popular social media platforms, has been repeatedly accused by the government of illegally collecting children’s data and failing to respond to parental requests to delete their children’s accounts. to respond to parents’ requests to delete their children’s accounts. A survey by the Pew Research Centre found that more than 60% of American teens aged 13-17 use the platform, with more than half of them using it daily. Data is revenue, and it is hard for platforms to give up that revenue under self-regulation.

Similarly, Youtube was fined $170 million in the US for violating children’s privacy. This is the highest fine ever recorded by Coppa and the video streaming site was accused of collecting data on children under 13 without parental consent. The US Federal Trade Commission said the data was used to target adverts to children, in violation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (Coppa).

Different countries have different levels of legislation for privacy. There is the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2018 or Australia’s Privacy Act 1988. The protection of data and human rights is constantly being refined.Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Bill 2024 alone provides additional protection for children in high privacy risk practices.

User: Who is Really Responsible

Access to the Internet or other digital tools, should be seen as a human right in itself, which would create a positive obligation for states to ensure connectivity — Kari Karppinen

A serious issue is that “privacy” as a concept should be about the individual being free from the observation and intrusion of others (Marwick & Boyd, 2018). But living in the digital age makes achieving privacy particularly difficult, with the influence of platforms touching every aspect of life. Platforms collect data and decide what to push based on algorithms. As recipients of information, users get biased by adverts and politics from platforms. Adverts and political messages that are not supported by the platform cannot be seen and gradually disappear from the information flow of the internet. Information is collected, traded, and analysed in exchange for the platform’s biased basic services.

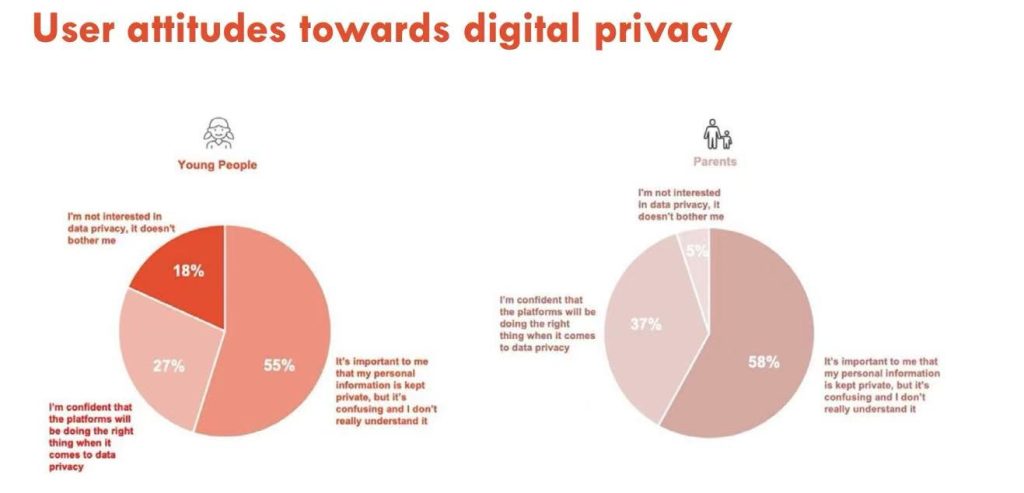

Figure 2:User attitudes towards digital privacy

Source:Humphry, J., Boichak, O.& Hutchinson, J. (2023) Emerging Online Safety Issues –Co-creating social media with young people Research Report. The University of Sydney.https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/31689/USyd_Emerging%20Online%20Safety%20Issues_Report_WEB.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

The good news is that people realise the importance of digital privacy. According to 2023, 55% of young people think it’s important to keep their privacy, and 58% of parents also think personal information is important. Less than 20% don’t care about it. Users realise the importance of holding platforms accountable, and professionals, students, parents and governments can use this to call for a regulatory regime for platforms. Whether the algorithms are transparent and the information obtained follows the principle of contextual integrity. Public organisations, given some real rights to enforce governance over platforms. karppinen (2017) reminds us that human rights must be at the heart of digital governance. This means that access, expression and privacy should be seen not only as features but also as rights. Upholding human rights principles as existing legal norms should represent the normative vision of the information and communication policies that are formed. This is about democracy, freedom and the digital future we want to build.

Conclusion

Figure 3:News of Australia’s social media ban is attracting global praise

Source:Taylor, J. (2025, April 05). Australia’s social media ban is attracting global praise – but we’re no closer to knowing how it would work. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/apr/05/australia-social-media-ban-trial-global-response-implementation

In the digital environment, the security of data relies on the protection of technology companies. At the same time, the concept of digital privacy is gradually becoming clearer and more important to users. States should give third parties the right to digital governance, rather than handing over all rights to digital platforms, which can create an imbalance of power. Australia’s social ban was praised around the world, which is a good start. The excessive rights of the digital platforms make the implementation of this rule unpredictable. As Flew (2021) states, “the right to privacy is not an absolute human right, but one that is grounded in particular social and legal contexts. “The digital future relies on governments, platforms and users to build it together.

References:

Australian Government. (1988). Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

BBC News. (2019, September 05). YouTube fined $170m in US over children’s privacy violation. BBC News.https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-49578971

Cadwalladr, C.& Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 18). Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election#:~:text=The%20data%20was%20collected%20through,in%20the%20US%20presidential%20election.

European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, L 119, 1–88. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 72-79.

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., Bailo, F. (2017) Executive Summary and Digital Rights: What are they and why do they matter now? In Digital Rights in Australia. Sydney: University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587

Humphry, J., Boichak, O.& Hutchinson, J. (2023) Emerging Online Safety Issues –Co-creating social media with young people Research Report. The University of Sydney.https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/31689/USyd_Emerging%20Online%20Safety%20Issues_Report_WEB.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Jenny Ware MP. (2025, January 07). Online Safety Amendment Social Media Minimum Age Bill 2024 Second Reading[Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uYf_x4NYaZQ

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1157–1165.

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting Context to Protect Privacy: Why Meaning Matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Bill 2024 (Cth) (Austl.).

Sherman, N. (2024, August 03). TikTok sued for ‘massive’ invasion of child privacy. BBC News.https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cllyl14mr8lo

Suzor, N. P. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives (pp.10-24). Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, J. (2025, April 05). Australia’s social media ban is attracting global praise – but we’re no closer to knowing how it would work. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/apr/05/australia-social-media-ban-trial-global-response-implementation

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

Be the first to comment