Don’t Underestimate That One Video You Just Watched

Ever noticed how TikTok, YouTube, or Netflix always seem to show you exactly what you’re in the mood for—even when you’re not quite sure what that is? The longer you use them, the more it feels like they truly “get” you. But here’s the twist: are these platforms becoming more attuned to us, or are we slowly adapting to what they want us to be?

This isn’t just about clever recommendations—it’s a subtle form of control. Today’s tech systems—recommendation engines, automation tools, decision-making software—go beyond convenience. They quietly influence what we see, how we think, and sometimes, what opportunities we get (Flew, 2021).

This article takes a closer look at the not-so-obvious ways AI, algorithms, and data systems are shaping our daily experiences. We’ll unpack how they work, what power structures they reflect, and what it takes to make these systems more transparent, fair, and human-focused.

Beyond Sci-Fi: AI as a Global System

When we hear “AI,” most people imagine robots, voice assistants, or something like ChatGPT. But real AI isn’t just a smart piece of code—it’s a vast network built on global labor, massive data sets, and energy-hungry infrastructures.

As Kate Crawford (2021) explains, AI is not magic. It relies on physical resources and social systems. Training a model like GPT takes enormous datasets, thousands of human annotators, and energy-intensive data centers. Behind the sleek interfaces are invisible costs—environmental damage, data labor, and power inequalities.

So no, AI isn’t just a neutral tool—it’s political. Its development reflects who owns the data, who gets to design the systems, and whose interests are being served (Crawford, 2021). If a hiring algorithm is trained mostly on data from Western countries, how well does it understand applicants from elsewhere? Does it replicate old biases—or challenge them?

Instead of thinking of AI as a blank slate, we should see it as a machine that inherits and amplifies the social norms embedded in its design.

Are We Still Choosing, or Just Following the Feed?

Many of us think algorithms help us save time: which video to watch next, which products to buy. But Terry Flew (2021) points out that this is a new form of governance—where behavior is guided and shaped automatically by platforms.

Every scroll on TikTok, every like on Instagram, feeds a profile of who you are. In return, the system delivers what it predicts you’ll engage with. It feels like choice, but it’s pre-filtered, optimized, and subtly nudges you in directions you may not have chosen on your own (Flew, 2021).

And sometimes, the consequences go beyond entertainment.

🎯 Case 1: Hiring by Algorithm

More and more companies are using automated tools to screen job applicants. Systems like HireVue analyze facial expressions, tone of voice, and even word choice to assess your potential. The problem? These systems are often black boxes—and they’ve been accused of unfairly disadvantaging non-native speakers, women, and people with darker skin tones (Raji & Buolamwini, 2019).

🎯 Case 2: The Smart City Dilemma

In some Chinese cities, AI-powered surveillance helps manage traffic and public behavior. But once these systems are tied to social credit scoring, daily activities—jaywalking, smoking, repaying debts—can affect your ability to book transport, access loans, or even get a job (Flew, 2021).

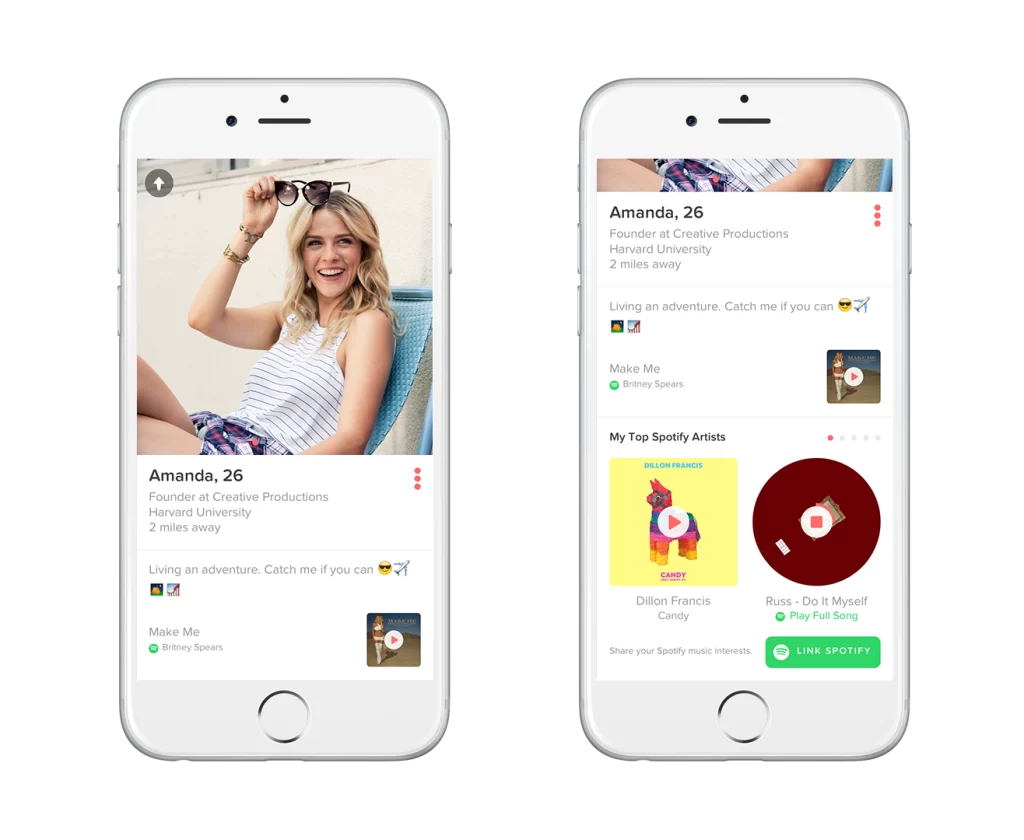

🎧 Spotify: Helping You Discover Music or Trapping Your Taste?

Think about the last time you discovered a new song—was it from a friend, or from Spotify’s “Discover Weekly”? As convenient as it is, Spotify’s recommendation algorithm tends to reinforce what you already like. The more you listen to a certain genre or artist, the more the platform gives you similar content. Over time, your musical world can become smaller without you realizing it.

Researchers call this the “filter bubble” effect. A system meant to help you explore ends up limiting your range. For emerging artists or diverse genres, breaking into your feed becomes nearly impossible if the algorithm doesn’t think you’d be interested. This raises a deeper question: if platforms know us too well, are we still making choices, or just living inside a curated loop?

🧪 When AI Grades Your Future: The Education Crisis

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, students in the UK couldn’t take standard exams. To solve this, the government turned to an AI system to estimate final grades based on past school performance, location, and other factors. The result? Thousands of students—mostly from lower-income or underperforming schools—received much lower scores than expected.

Public backlash was immediate. Critics argued the algorithm had reinforced systemic inequalities by assuming students from historically weaker schools were less capable. After protests, the government scrapped the system and reverted to teacher predictions.

This case is a stark reminder: AI used in high-stakes situations can entrench bias, especially when its logic isn’t transparent or accountable. And when there’s no way to appeal, it’s the students who suffer the consequences.

Bias Is Built In: Why Technology Isn’t Neutral

It’s tempting to think of AI as logical and unbiased—but algorithms often reflect the same prejudices we see in society (O’Neil, 2016).

Take the COMPAS system in the US. Designed to predict criminal reoffending, it was found to label Black defendants as “high risk” far more often than white defendants in similar situations (ProPublica, 2016).

Algorithmic bias is one of the most serious and insidious problems in AI. It shows up in:

- Job screening tools that filter out resumes based on gender, race, or name.

- Credit scoring systems that penalize users based on zip code or purchase history.

- Facial recognition systems that misidentify people of color at much higher rates (Raji & Buolamwini, 2019).

🔍 Problem 1: Black Box Systems

These tools often lack transparency. Even the companies behind them can’t always explain how decisions are made (Pasquale, 2015). That’s a major issue when algorithms are making calls that affect real lives.

🔍 Problem 2: Too Much Power in Too Few Hands

Today, AI is dominated by a handful of tech giants—OpenAI, Google, Meta, Amazon. These companies control the data, the infrastructure, and the development priorities. That means AI isn’t evolving for the public good—it’s being shaped by corporate interests (Crawford, 2021).

Crawford (2021) highlights the hidden cost of this setup: low-paid data workers in the Global South, massive carbon footprints, and unchecked data harvesting. This isn’t just about efficiency—it’s about a digital form of colonialism.

Can We Design Tech That Works With Us?

It’s easy to critique AI. But what if we designed it better from the start?

That’s where the concept of “governance by design” comes in—baking values like privacy, fairness, and inclusiveness into technology at the design stage (Binns, 2018).

For example, Apple’s one-time location access feature is a privacy-friendly design choice. Explainable AI is another push: imagine being told why a system made a decision and how to fix it (Pasquale, 2015).

Some companies are also working on more balanced datasets to prevent systemic bias (Raji & Buolamwini, 2019). Google’s newer image projects, for instance, now include more representation from the Global South.

🧠 Design With Real People in Mind

User-centered AI should account for cultural and linguistic differences. A chatbot that misunderstands urgency or tone because it wasn’t trained on diverse communication styles is a problem.

That’s why participatory design matters—people affected by AI should have a say in how it’s built (Binns, 2018).

🔮 Reimagining AI for the Public Good

What if you could adjust your recommendation feed like a thermostat? Dial down the addictive content and increase diversity? What if public institutions built their own open-source platforms where people could co-design the rules?

Imagine AI systems managed like public utilities—transparent, accountable, and open to citizen input. It sounds idealistic, but it’s not impossible. Participatory models exist in other areas of governance; why not in tech?

As long as AI systems are developed only behind corporate doors, they will serve narrow interests. But if we make space for democratic participation, we may get closer to technologies that truly reflect collective values.

What Can We Actually Do?

It’s not just about tech experts. All of us have a role to play in shaping how AI affects society.

🧭 Step 1: Push for Stronger Rules

- The EU’s AI Act proposes different tiers of regulation based on system risk (European Commission, 2021).

- UNESCO’s ethical guidelines promote inclusive, sustainable AI development (UNESCO, 2021).

- In Australia, ethical AI principles call for fairness, reliability, and transparency (Flew, 2021).

🧠 Step 2: Everyday Actions Matter Too

- Be more conscious of how your data is collected and used.

- Join conversations around tech ethics—online, in communities, in education.

- Support tools and platforms that prioritize privacy and openness.

- Speak up when platforms cross ethical lines.

🧩 Why This Conversation Isn’t Just for Tech Experts

Now, you might be thinking, “Okay, but I’m not a software engineer or data scientist—does any of this really involve me?” And the honest answer is: yes, more than ever.

You don’t need to understand how neural networks are built to have an opinion on how they affect your life. You don’t need to write code to notice that certain videos seem to follow you everywhere, or that you’ve stopped seeing things outside your usual bubble. You don’t need to be an “AI insider” to ask: Who made this decision? Why wasn’t I told? Can I opt out?

The truth is, many of the most important decisions about AI are happening far from the public eye, in conference rooms, cloud servers, and back-end dashboards. But that doesn’t mean they’re beyond our reach. Even small actions—questioning a feature, reading critically, choosing ethical platforms—are part of a larger cultural shift that demands accountability.

In a world where nearly everything is personalized, optimized, and tracked, simply pausing to notice is powerful. And sharing that awareness? Even more so.

🌱 The Everyday Rebellion: Choosing Intention in a World of Automation

It’s easy to let life run on autopilot—scrolling, clicking, tapping through our days. And in many ways, technology is built to encourage that. But sometimes, the most radical thing we can do is simply slow down and notice: Why did this video appear in my feed? Why does this app want my location? Do I even need to know this news right now?

Practicing digital awareness doesn’t mean unplugging entirely or rejecting technology. It means using it with curiosity instead of just convenience. It’s about choosing intention over automation. Because in a world designed to keep us passive, choosing to pay attention is a quiet form of rebellion.

Whether that means adjusting your settings, supporting ethical alternatives, or simply talking to friends about how platforms make decisions—that’s part of governance too. Change often starts with small questions.

Final Thoughts: Take Back the Decision-Making

AI is already intertwined with our lives—from the videos we watch to the jobs we get to how we see the world (Flew, 2021).

That’s why we need to stay aware, stay curious, and ask harder questions.

Tech should work with us, not against us. And the future of AI shouldn’t be decided behind closed doors—it should be open to all of us.

Because ultimately, we’re not powerless. We just haven’t been heard loudly enough—yet.

Reference List

Binns, R. (2018). Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (FAT), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287598

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

HireVue. (2020). AI-driven hiring and candidate assessment. https://www.hirevue.com

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown Publishing Group.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

ProPublica. (2016, May 23). Machine bias. https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

Raji, I. D., & Buolamwini, J. (2019). Actionable auditing: Investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314244

UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137

All image from media library.

Be the first to comment