Across South Korea, young men are turning to online forums like DC Inside to express frustration around gender equality — and increasingly, that frustration is taking the form of misogyny.

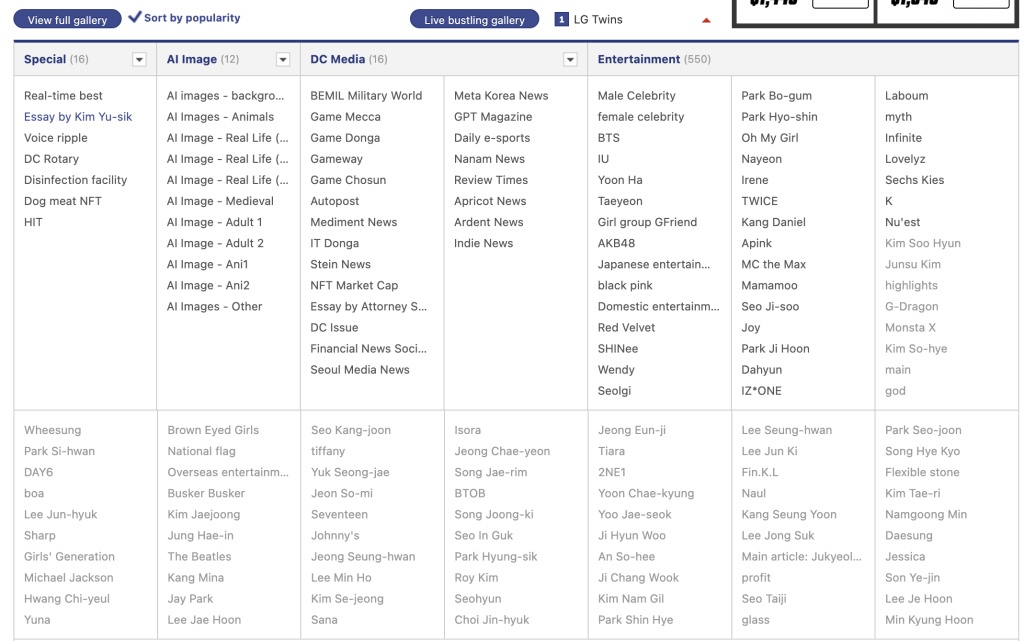

Launched in 1999, Digital Camera Inside (DC inside) is the most-visited website in South Korea as of Feburary 2025 (Similar Web), originally a digital photography forum for the local Korean market. The platform has since evolved into one of the country’s most influential and chaotic online spaces. It now hosts thousands of anonymous ‘galleries’(sub-forums), covering everything from memes and fandom discourse to civic and political commentary, all with minimal moderation.

While some galleries remain light-hearted, others have become breeding grounds for hate speech and incel rhetoric. One such space, the now-removed “feminism gallery“, received heavy public criticism and was eventually shut down by DC Inside due to the volume of extreme and harmful content. A space created not to support feminism but rather a space to mock, attack, and satirise feminist ideas and figures.

South Korea’s rise in anti-feminist and misogynistic rhetoric reflects deeper systemic issues around hate speech and online harm, where its regulations and platform governance reveals it is shaped by cultural bias, limited legislation, and underdeveloped platform governance. This raises urgent questions about the responsibilities platforms hold and whether current models of self-regulation are sufficient — or if deeper systemic issues in governance and platform design must be addressed. This blog post argues that self-regulating platforms, driven by engagement-focused algorithms, are failing to address culturally embedded forms of online hate speech, highlighting the need for stronger, culturally responsive digital governance.

The Cultural Roots of Online Misogyny in Korea

While misogyny isn’t exclusive to South Korea, the rise of outspoken anti-feminist online communities suggests there are deeper, locally specific tensions fueling it.

South Korea offers a particularly sharp lens for understanding how cultural resentment can turn into online hate. The country’s mandatory military service for men, paired with the increasing academic and professional success of women, has led to a perception among some young men that feminism is no longer about equality — ‘it’s an attack on men’ (Chen & Kwon, 2022). This has given rise to a vocal and emotionally charged anti-feminist backlash, particularly visible online.

Yet, data from The Economist’s 2024 Glass Ceiling Index contradicts these beliefs. South Korea ranks last among OECD countries for gender equality, with some of the worst scores for wage equality and political representation. This reveals a disconnect between perception and reality. While some men believe feminism is overreaching, the data shows that gender inequality remains deeply rooted in Korean society.

In this climate of emotional frustration and cultural misperception, digital platforms have become more than just forums for discussion. They become amplifiers of resentment and incubators of hate speech. This is why South Korea provides a compelling case study for examining the intersection of cultural context, platform design, and weak moderation — as seen through platforms like DC Inside.

Defining Hate Speech in a Korean Digital Context

Hate speech is commonly defined as speech that “expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, or sexual orientation” (Parekh, 2012, p. 40). While useful as a baseline, this definition focuses narrowly on incitement — often missing how hate speech operates more subtly in coded, culturally embedded forms.

Sinpeng et al. (2021) provide a more critical and context-responsive definition of hate speech: speech that “discriminates against people on the basis of their perceived membership of a group that is marginalised, in the context in which the speech is uttered.” This approach shifts the focus from incitement alone to systemic harm and marginalisation, making it more useful for platform regulation and policy-making.

In societies like South Korea, where patriarchal values shape both digital culture and institutional governance, this broader lens better explains how misogynistic rhetoric becomes normalised and why platforms must be held accountable for enabling it.

Flew (2021) expands on this by highlighting the real-world harms of online hate. From Gamergate to the Christchurch mosque shootings, he shows that hate speech, when left unchecked can escalate beyond offence into violence and long-term social damage. His framework reinforces the need to regulate based on harm, not just offence.

Parekh’s (2012) definition, while foundational, doesn’t fully account for the coded misogyny present in Korean digital spaces. As Jinsook Kim (2018) explains, users often hide hate behind slang and humour such as “femi-bug” or “soybean paste girl” which dehumanise women while avoiding moderation. These expressions enable hate to thrive beneath the surface.

How Platform Design Amplifies Gender-Based Hate

The persistence of online misogyny in South Korea isn’t just about individual users — it’s also a product of how platforms are built. As Crawford (2021) and Just & Latzer (2017) argue, platforms are not neutral spaces. They reflect corporate priorities, political bias, and the power structures of those who create them.

Algorithms on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and DC Inside don’t just show what’s popular — they curate and amplify content that drives engagement. What drives engagement? Outrage, spectacle, and emotionally charged content. This means misogynistic posts are not just tolerated — they’re rewarded.

This is what Just & Latzer describe as “governance by algorithms”: repeated exposure shapes what users see, value, and believe. One anti-feminist video leads to another; one hostile gallery leads to more. Over time, users are pulled into feedback loops that reinforce extreme views.

The result is not just exposure — it’s radicalisation, normalisation, and desensitisation. Harmful content becomes familiar, casual, and harder to recognise — often framed as humour or satire.

A clear example is the rise of anti-feminist YouTube channels like Man On Solidarity, which has gained a large following through emotionally provocative and misogynistic content. This shows how platforms are not just failing to regulate harm. They’re incentivising it.

How This Digital Culture Came to Be

In 2010, a new online forum called Ilbe — short for Ilgan Best Jeojangso or “Daily Best Archive” — emerged as a curated spin-off from DC Inside. Originally created to showcase the platform’s most popular posts, Ilbe quickly transformed into one of the most infamous corners of the Korean internet. What began as a content aggregation site evolved into a hub for far-right, anti-feminist, and ultra-conservative users. It intensified the misogynistic discourse already present on DC Inside, turning scattered resentment into a radicalised, tight-knit community built on trolling, hate speech, and ideological extremism.

By 2014, Ilbe had amassed over 100,000 registered users, reflecting not only its broad reach but also its resonance with disillusioned young male users. Its emphasis on “absolute” free speech and anonymous participation created fertile ground for a cultural incubator — one that helped shape and spread harmful narratives still visible in mainstream Korean digital culture today.

Many misogynistic slang terms still circulating today have roots in Ilbe-era culture:

- 삼일한 (samilhan) — “women must be beaten every three days”

- 김치녀 (kimchi-nyeo) — “kimchi bitch”

- 보밍반 (bomingban) — “banning out,” referring to the practice of banning users who reveal they are women.

These terms, often disguised as humour or satire, justify gender-based hostility by caricaturing Korean women as vain, selfish, or manipulative (Jinsook Kim, 2018). Misogyny wasn’t just tolerated in these spaces — it was gamified and embedded into the culture of participation. This coded, casual hatred gave rise to coordinated attacks on women, including doxxing, harassment, and cyber witch-hunts.

This reflects a broader issue in South Korea’s online culture, where platforms — particularly those that are anonymous and emotionally charged — enable hate speech to flourish. In the absence of strong moderation or culturally responsive governance, these platforms don’t just tolerate misogyny; they structurally enable and normalise it.

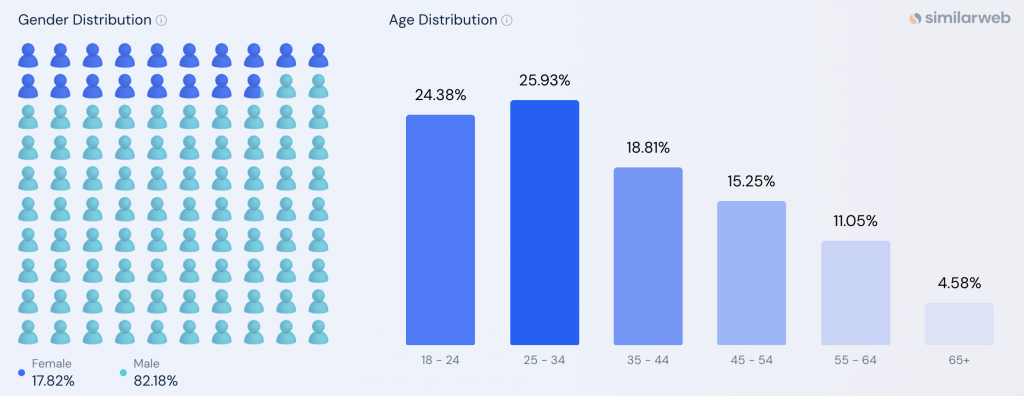

Data from SimilarWeb shows that over 82% of DC Inside users are male, with the largest age group being 25–34 years old. This reflects the platform’s ongoing appeal to young men — the demographic most associated with South Korea’s online anti-feminist backlash.

Gaps in Governance: Why Regulation Fails to Address Online Gender-Based Hate

Misogynistic hate speech in South Korea is not simply the result of individual user behaviour — it reflects deeper structural failures in law, culture, and platform governance. Despite growing public concern, South Korea still has no comprehensive hate speech law. Existing legal tools, such as defamation or sexual harassment statutes, apply only to cases involving individual victims and are not designed to address group-based online hate (Kim, 2024). As a result, misogynistic attacks on feminists and gender-based slurs often fall through regulatory cracks.

A 2019 report by the Human Rights Commission of Korea shows the consequences of this gap:

According to the Youth Awareness Survey, approximately 7 out of 10 youths were exposed to hate speech (68.3%). The most common hate speech was related to women (63.0%), followed by sexual minorities (57.0%). 82.9% of youth who were exposed to hate speech came across hate speech on the Internet. — particularly across social media and platforms like YouTube.(Human Rights Commission of Korea, 2019)

Despite this, legal and policy responses remain fragmented and poorly enforced.

Policy gaps are compounded by weak institutional enforcement. The Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC), South Korea’s primary media regulator, technically prohibits discriminatory content — enforcement is vague and inconsistent. Researchers have criticised the KCSC for disproportionately censoring feminist content while allowing misogynistic speech to remain (Kim, 2024). . This reflects a broader institutional imbalance, where content moderation systems reproduce the same patriarchal biases they should be regulating.

As Kim (2024) explains, Korea’s regulatory shortcomings are not just legal — they’re cultural. Efforts to regulate online misogyny often face backlash framed as protecting freedom of expression. Many believe gender discrimination is no longer an issue, and President Yoon’s administration has pushed to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality under the claim that feminism has gone “too far.” These cultural and political attitudes shape how regulation is resisted, misapplied, or ignored.

Together, these structural gaps — weak laws, vague enforcement, and cultural backlash — create a digital environment where misogyny thrives. Platforms like DC Inside and YouTube profit from emotionally provocative content, while institutional actors fail to intervene. Without stronger regulation and culturally responsive governance, hate speech is not just tolerated — it is enabled and normalised.

Conclusion

This blog has examined how misogynistic hate speech in South Korea stems not just from individual users, but from a broader system of platform design, weak regulatory frameworks, and culturally biased moderation. Through the case studies of DC Inside and YouTube, it explored how algorithmic amplification, the absence of comprehensive hate speech laws, and uneven enforcement enable anti-feminist rhetoric to thrive online. Drawing on scholars like Crawford (2021), Just & Latzer (2017), and Sinpeng et al. (2021), it argues that self-regulation is no longer sufficient. Effective governance must address cultural context, structural bias, and the algorithmic systems shaping digital discourse.

References

Chen, H., & Kuon, H. (2024, March 8). Young, angry, misogynistic, and male: Inside South Korea’s incel problem. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/south-korea-incel-gender-wars-election-womens-rights/

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1ghv45t

Flew, T. (2021). Hate speech and online abuse. In Regulating platforms (pp. 91–96). Polity Press.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Kim, J. (2018). Misogyny for male solidarity: Online hate discourse against women in South Korea. In J. Vickery & T. Everbach (Eds.), Mediating misogyny (pp. 135–157). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6_8

Kim, M. (2024). Online gender-based hate speech in South Korea. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 38(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2023.2295093

National Human Rights Commission of Korea. (2019). A report on hate speech.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin.

Similarweb. (2025). Top websites ranking in Korea, Republic of. https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/korea-republic-of

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F., Gelber, K., & Ralph, N. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

The Economist. (2024, March 7). The glass ceiling index. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/glass-ceiling-index

Be the first to comment