Introduction

In March 2025, American internet celebrity Speed came to China to broadcast live, and Li Meiyan served as an accompanying interpreter. He caused controversy on the Internet because he repeatedly used the phrase “chick in China” to introduce Chinese women during the broadcast live. “Whether the phrase is insulting and objectifies Chinese women”, Li Meiyan denied having made insulting remarks, using the excuse of language and cultural differences.

We use this recent and representative incident as a starting point to explore the phenomenon of malicious attacks on the Internet that have long been suffered by the entire group of Asian women, extending from the perspective of “Chinese women,” including the hidden oppression within the same cultural context and the persistent hate speech involving different races. One particular phenomenon is worth noting—many Asian women are maliciously attacked without knowing it. Have you ever come across comments like “Asian girls are all well-behaved and cute”? It may not sound malicious, but is it really just a compliment?

The reason for this phenomenon is not only a single structural problem of gender discrimination, but also involves deeper issues at the racial, cultural, and national levels. Asian women have been suffering from a special but unseen hidden storm.

Definition of hate speech and common misconceptions

The vicious attacks on Asian women on the internet are not a sudden or isolated phenomenon, but the result of a long-term accumulation of stereotypes and the interplay of social and cultural structures. Asian women have traditionally been portrayed in Western media as “well-behaved, deeply family-oriented, and overly submissive”. These labels are repeatedly spread and consumed on the internet, reshaping public attitudes and exacerbating implicit prejudice against Asian women in the process.

The general public with non-academic backgrounds often equate hate speech with a single abusive act or a threat of violence. This public perception may, to some extent, reduce the harm and impact of more deceptive hate speech, which is more like a sneaky insult behind someone’s back. For example, Chinese women may ignore non-stereotypical hate speech in English due to language barriers.

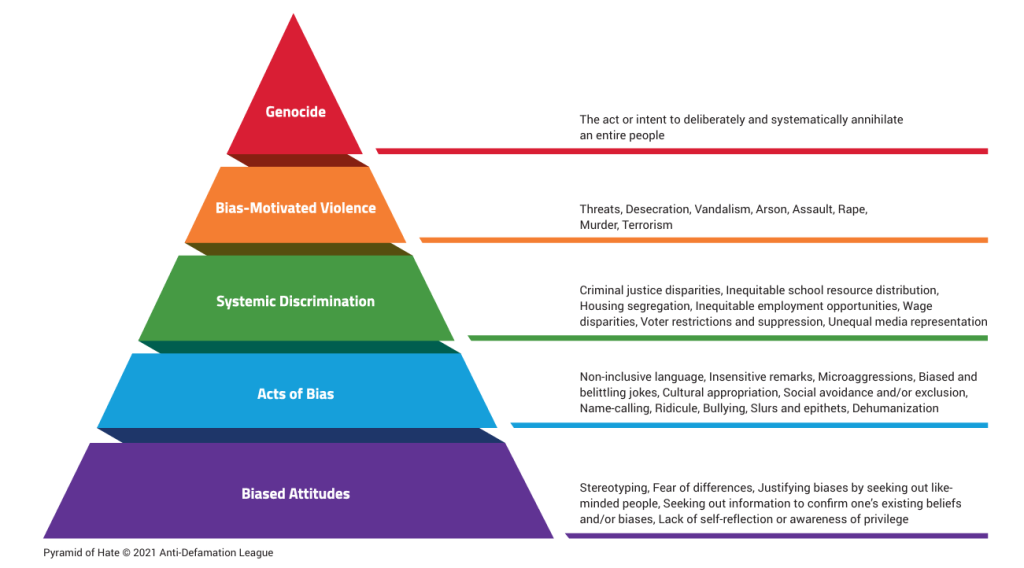

In academic definitions, hate speech is a form of discursive discrimination that targets its objects, deprives them of equal opportunities and violates their rights, much like other acts of discrimination (Gelber, 2019, p5-6). Flew, on the other hand, emphasizes the “institutional harm” of hate speech, pointing out that such speech may cause lasting structural exclusion and fear in society (Flew, Terry, 2021). The public’s one-sided understanding of hate speech does not mean that the malicious nature of hate speech can be concealed. The judgment of whether a joke is malicious or not should be left to the collision of opinions between the sender and the receiver, which will generate a dynamic interactive process and to some extent reach a consensus on “harmfulness”.

Hate speech does not simply use violent rhetoric. It also deprives groups of their dignity and sense of belonging in society. It is through this mechanism that covert malice operates. It reduces Asian women to symbolic stereotypes and often subjects them to malicious attacks from others without their knowledge.

Explicit and non-explicit hate speech

Asian women have long been the object of gaze on social media platforms, and this identity position determines that when the labels “Asian” and “woman” appear in the public eye, they have to passively endure malicious comments from all directions. It is like being at the center of a whirlpool. These malicious comments can be divided into explicit and non-explicit. Explicit malicious comments refer to those direct and offensive comments that are clearly discriminatory and insulting, such as the term “chick in China” that Li Meiyue mentioned repeatedly. and non-obvious maliciousness refers to those expressions that contain humiliating and objectifying meanings hidden without the use of iconic insulting words. For example, when Asian women post videos of dancing or wearing slightly revealing outfits on Tiktok, the comment section often appears with comments like “who would marry a woman like this?” and “it’s to get PR from marrying a white man,” which are expressions of gender oppression and insults.

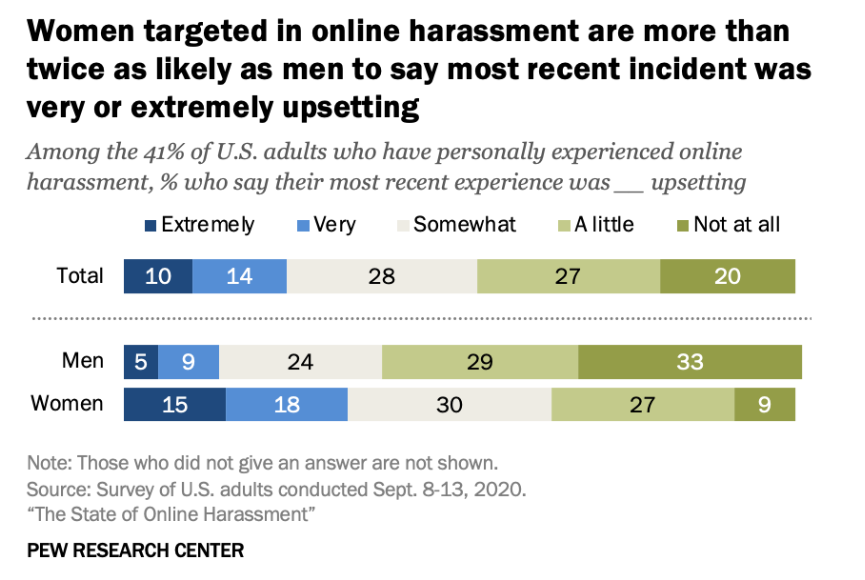

Women and girls reported more hate acts to Stop AAPI Hate than men and boys (62% vs. 29%).13 Women and girls also reported more experiences with intersectional and coded bias than men and boys (13% vs. 6% and 23% vs. 19%respectively)(Stop AAPI Hate Reports,p5),This means that Asian women are much more likely to experience hate incidents than men. A 2021 study by Pew Research Center also shows that”Women who have been harassed online are more than twice as likely as men to say they were extremely or very upset by their most recent encounter (34% vs. 14%).“

However, in reality, it is not easy to distinguish non-obvious malicious speech. Such speech is often disguised as “jokes” or “cultural differences”. The possibility of such speech escaping the monitoring of platform algorithms is higher than that of obvious speech. Even if it appears in the public eye, it is difficult to immediately recognize it as “hate speech”. For example, comments such as “Asian women are very suitable for marrying into the family” or “Asian women are good at housework” may seem like compliments, but in fact they hide gender stereotypes and racial desires. This blurring of boundaries also makes non-obvious malice the most lethal weapon in hate speech, the most difficult to guard against and the most difficult to realize.

How hate speech is filtered and spread by platforms

In China’s social media ecosystem, platforms such as Weibo, Rednote, and Bilibili regulate content to filter out representative hateful content and abusive words to prevent the spread of explicit hate speech. On the surface, this mechanism is intended to protect the targets of attacks, but in reality, it has given rise to a set of linguistic strategies to circumvent platform censorship. For example, words with similar pronunciations are used instead of words that would otherwise be blocked by the platform. These types of “edge-ball” behaviors, which evade platform regulation, will exacerbate the spread of a new wave of hate speech and and attach a new layer of meaning to words that do not originally have a hateful or insulting meaning. This not only deepens the covert nature of hate speech, but also makes its spread within the platform more deceptive and destructive.

Content moderation on platforms often focuses more on “surface moderation” than on in-depth judgment and consideration of word meanings and cultural backgrounds (Roberts, S. T., 2019, Behind the Screen). In addition to the regulatory failure of platforms to govern non-explicit hate speech, the algorithmic recommendation has also played a negative role in promoting the spread of explicit and non-explicit hate speech. For example, during the Youtube live broadcast of IShowSpeed’s China tour, the term “chick in China” was further expanded along with the live stream of the broadcast. The platform did not respond in time when the term first appeared during the broadcast, causing Chinese women to be further hurt after receiving the system-recommended video. This kind of platform’s default algorithm recommendation and lack of content review has left Asian women with almost nowhere to turn when faced with online hate speech and insulting terms, and they are even victimized twice.

The algorithms of platforms for recommending content have a commercial underlying logic. They often prioritize pushing content that is controversial or likely to cause controversy in order to increase views and interactions, thereby amplifying “toxic culture”. Sarah Roberts (2019) also criticized the superficial content moderation of social media platforms, which has resulted in the systematic and long-term neglect of some groups. These mechanisms not only fail to limit the spread of hate speech, but often become its accelerator.

An Asian woman’s way out of non-explicit hostility

In the online space where English is the main language, to break the situation where Asian women have long been plagued by “non-explicit hate speech”, we need to start from the perspective of the attacker and strengthen their media literacy and cultural awareness. Not only should they be bound by morality, but they should also be aware of the wrong behavior they are doing at the social structural level. For the victim group, how to realize that those words that they cannot read, understand, and seem to have no problem with are actually power appropriation and objectification and humiliation, This requires the construction of a complete language support system. Very often, public expression is abandoned because of doubts about whether one is being too sensitive, with thoughts like “the other person probably didn’t mean it that way” or, after being attacked, refuting the comments with “you girls are just too sensitive”.Platforms should develop more localized language recognition systems so that individuals have channels to feedback, seek help and get solutions when they feel uncomfortable or offended.

In addition to technical precautions, a more respectful and inclusive online culture can only be truly established with the long-term support of media education and institutional reforms. Intercultural media literacy courses should be incorporated into public education to raise awareness of the meaning of texts in different contexts. When individuals, platforms and institutions work together, Asian women will truly be respected in cyberspace.

Conclusion

With the rise of women’s consciousness within the Internet, more and more Asian women dare to speak out, from simple users to celebrities, from platform feedback to legal means. Asian women who have been attacked by hate speech are breaking their silence and the unilateral malicious attacks of their attackers. In the public space, the voices of Asian women are gradually becoming more persuasive, and the awareness of Asian women’s equality has been valued in the entire online ecosystem, so that silence is no longer silence.

In short, the most harmful aspect of online hate speech against Asian women is often not the violent cursing or threats of violence, but the neutral language that is couched in everyday vocabulary. Because it “sounds less offensive,” it is more likely to be ignored, more difficult to resist, and even ultimately tacitly approved of by society. The real danger of this kind of discourse is that it quietly normalizes discrimination, making the victim accept this value output and voluntarily cede power.

Solving this problem requires a thorough cultural awakening. We must re-examine the excuse of “joking” and reflect on the power structures behind the language. In order for Asian women to truly be “seen and respected” in cyberspace, we must not only say no to explicit hatred, but also expose the hidden violence hidden in everyday speech to public judgment.

So, the next time you see or hear something that seems fine, but makes you feel uncomfortable, think twice: “Is there really nothing wrong with this?” Sometimes, just being more aware is a form of resistance.

Reference

Gelber, Katharine. (2019). Differentiating Hate Speech: A Systemic Discrimination Approach. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy. Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2019.1576006

Flew, Terry .(2021). Hate Speech and Online Abuse. In Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 91-96

Stop AAPI Hate. (2023, October). Key findings from the 2023 taxonomy report [Report].https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/23-SAH-TaxonomyReport-KeyFindings-F.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2021, January 13). The state of online harassment. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media. Yale University Press.

Be the first to comment