Open TikTok and within seconds, it’s already in your head. A dog that looks just like yours. A stranger joking about your secret insecurities you’ve never even seen before. A political opinion you didn’t even know you had until now. TikTok knows you. It feels personal—like magical.

But there is a dark engine behind that magic—the algorithmic puppeteer pulling strings you can’t even see.

And here’s the thing: Behind TikTok’s viral content is an impossibly powerful algorithm—a computer-driven artificial intelligence system that learns you by watching what you watch. So every second you stay on a video, every swipe, like, and pause becomes a trial of data that TikTok uses to tweak what you watch next. And that’s not just for comfort or entertainment. It’s for control. And the infamous “For You Page” is not only showing what you want; it makes what you like. And while the page may be creator-made for you, it’s really meant for someone else: advertisers, corporations, the whole business model of surveillance capitalism.

But that leads to some bigger questions. Who actually controls what you see now? And what voices are being pushed or buried? Moreover, who’s to blame if platforms like TikTok are shaping our understanding of the world?

Let’s start by looking at why it’s so hard to stop scrolling on your TikTok page.

The Attention Trap: TikTok Turns Your Data into Dollars

We can all admit we have been there before. “I was just going to check TikTok ‘for 5 mins'” and before you know it, an hour has passed by. The app knows more about you than your friends do – what tickles you, what tears you, what’s clicking, what scrolling. This isn’t a coincidence; this is a business plan.

At the heart of TikTok’s FYP magic is a technology called surveillance capitalism. This term is introduced by scholar Shoshana Zuboff to define a system in which “human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data”. (Zuboff, 2019, p.8) Our behavior online – what we watch, what pausing time, what liking points there at most – our very own activities are no longer just of our entertainment but is being mined, analyzed, and sold.

Zuboff explains it best: digital platform like TikTok is “machine intelligence”. After our experience is turned into date, what she calls “prediction products”—

“…anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later … in order to nudge, coax, tune, and herd behavior toward profitable outcomes” (Zuboff, 2019, p .8)

– is ultimately created.

And while it works surprisingly, amazingly well. The more attention you pay to TikTok, the more data gets collected from you. Not only that but it is the stuff you want to be shared: this is what scholars call “data exhaust” —

the invisible trail of information you leave behind as you interact with content. Every scroll, tap, and second spent watching is fed into algorithms to keep you hooked (Lupton, 2016; Neff and Nafus, 2016).

There is no doubt according to the World Economic Forum that the new one is personal data. It is now considered the “new oil” (World Economic Forum, 2011, p. 5), the equivalent to something like capital or work nowadays: valuable resources.

That’s not where it gets weird things murky. And what we think is personal recommendations? It’s actually complex systems created so that they do not help me, but can make me click for as much as possible – for as long as possible. And not just long enough – for as long as possible. What was done for me? But used for me. So next time that perfect video lands in the Instagram feed just when you’re ready to watch it, keep this in mind: it’s not only convenient or fun. It’s also an advanced machine designed for one thing: hooking your attention, turning it into data feed, and then selling that data to whomever wants it most.

The cost of free entertainment? Your attention—and your actions going forward.

TikTok’s Brain Reading as Spying

TikTok’s brain-reading trick isn’t magic—it’s spying. Each tap, scroll, and millisecond of second-guessing is turned into a lab notebook. You’re no longer an interested user but a “data experience.” All of that tracking you do becomes part of your “profile.”

And guess what makes things get really wild here? You don’t even need to be looking at or searching for anything! TikTok’s algorithm doesn’t rely on what you say you are interested in—on your activity. Instead, it uses a model that it creates of who it thinks you are from how you behave. A lot less about what you say you like, and more about what you actually do. The scary part? It’s right. A lot of the time.

In this way, it’s a process of predicting what someone likes and doesn’t like. TikTok is not just a video platform organizing images and movies – it’s doing everything it can to manipulate you to be hooked onto the app. The algorithm is studying what sparks your emotions, what kind of stuff gets the best of you, and then serves up more of it, no matter if it’s good for you or not. It keeps you occupied.

As pointed out by Flew that “by onselling them to advertisers and third parties so as to enable them to better target consumers with their own products and services (Flew, 2021, p.107).” It’s for you to be on the app longer, so more ads can be made and so it can collect more data. That algorithm’s aren’t for you, they aren’t for being fair or open, or even right. They’re built for the amount of engagement that they can get out of you.

That’s why it’s so easy to drift into this black hole of content. Once TikTok has a sense of your patterns, it starts pushing more of the same, reinforcing your tastes and narrowing your view. It’s like living in a funhouse mirror that only reflects the parts of you that are most profitable.

You’re not just using TikTok. You’re training it. And while you’re being entertained, the system is getting smarter, sharper—and better at the gas hogging your hard-earned money.

Who Gets Seen, Who Gets Silenced?

TikTok’s “For You Page” seems to be a playing field that gives everyone equal chance at going viral. And let’s be real, it has launched loads of careers out of nowhere. But behind the scenes, the algorithm doesn’t simply play nice with all of us—this is when it gets hazy.

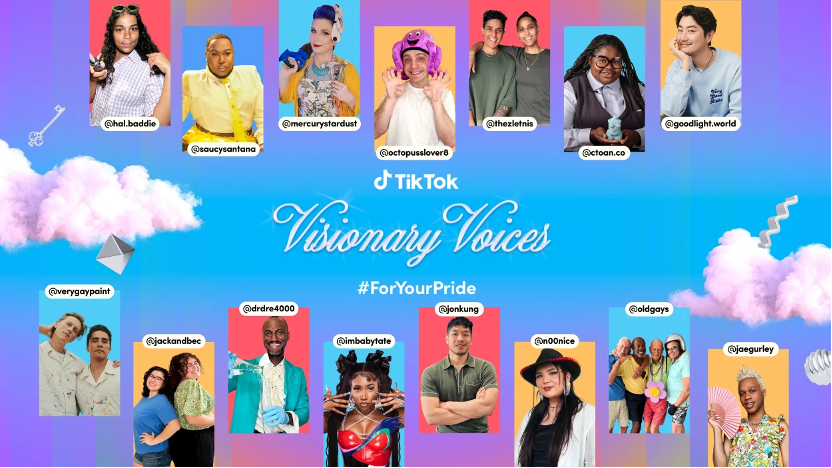

Try posting a status update Black, queer or disabled? The algorithm might just simply ghost you. Despite TikTok’s “For You” utopia, marginalized creators report their content going nowhere—not even an explanation, not an appeal. The Intercept’s 2020 leak confirmed it: TikTok quietly censored “undesirable” faces, from disabled users to the “poor-looking”! Their crime? Failing the platform’s “marketability test”.

This shows how platform governance isn’t neutral—it reflects the values and priorities of the companies behind it. This is so-called “platform politics”, where ‘the assemblage of design, policies, and norms … encourage certain kinds of cultures and behaviors to coalesce on platforms while implicitly discouraging others’ (Massanari, 2017, p. 336). The choices TikTok makes about what content is boosted or buried aren’t just technical—they’re political.

The platform may have said that “it lets everyone have a say,” but in reality, it’s the governing hand that controls who really has a say. This control persistently mirrors the same bias and hierarchy that we see in society: some voices are amplified; other voices are murmured. Meanwhile, users either don’t realize it’s happening at all or feel powerless against it.

And there is no public knowledge on how the algorithm works or why particular videos will appear. TikTok does not provide clear avenues to appeal moderation decisions. It’s done in an absolute vacuum, and this lack of transparency is a form of power, as well.

Why Platform Governance Matters

Right now, you might be thinking: “okay, the algorithm isn’t perfect, but isn’t that just how social media works? What’s the big deal?”

Well, the big deal is that TikTok isn’t just a fun app anymore. It’s where millions of people—especially younger generations (starting as young as preschoolers) —get their news, discover new ideas, establish communities, and even define their identities. When a platform has that much of place in people’s life, that’s when the way it works become important.

I’m here to say that TikTok’s algorithm does more than just put something out there; it shapes experience. It decides for us what we see and don’t see, what we come to believe is popular or true, who gets seen by whom.

“The production of calculated publics [or] the process of algorithmic presentation of publics back to themselves, and how this shapes a public’s sense of itself” (Musiani, 2013, p. 3).

When that power is driven entirely by commercial interests, we have a problem of governance.

The uncomfortable truth here is: TikTok’s algorithm is a “private governor” of public speech. Truth, popularity, and identity for millions of users are arbitrated by a single algorithm—or by a board of shareholders. Imagine if a city mayor operated this way: silencing “unprofitable” voices while claiming neutrality. We’d riot. But when mega humanities do it? We just keep scrolling.

Why we need stronger forms of platform accountability like TikTok? It’s not just about whether a dance video goes viral; it’s about who gets to speak, who gets heard, and who gets left out of the conversation entirely. Especially in today’s world increasingly determined and digitized through virtual reality, we cannot place those questions up to algorithms designed to deliver maximum advertising and minimum consideration for real people.

We need to grant ourselves harder questions. Not just “How will this algorithm work?” but “Whose interests is it being served?” or even worse, “What type of public life is this being created?” Because if we don’t, we sleepwalk right into a world where unseen systems dictate what our ideas and images become, and since we’re so distracted now, we don’t see.

So What Do We Do About It?

By now, it should not be surprising that TikTok’s “For You Page” isn’t about just feeding us fun videos, but rather a system using our data for profit and largely invisible in how it operates. TikTok is actually shaping a shared experience that reinforces the same old inequalities we see in real life.

Surveillance capitalism (TikTok) feeds off everything you like, post, or follow to create an algorithm that pools all information together that can be dug up and turned into money, making it something that is spread across social media platforms. But in doing so, it also reinforces a platform logic that engages over equity, who and how visible over diversity, and growth over responsibility. The platform doesn’t only echo our preference—curating what gets our attention focuses us on what’s most profitable and trends away from what’s complex, uncomfortable, or less “marketable”.

This matters because platforms like TikTok are now where culture happens, where voices rise (or fade out), and where public conversation is increasingly being hosted. And if we want that conversation to be fair, inclusive, and democratic, then we have to start thinking seriously about who’s in charge.

That does not mean shutting down the app or freaking out every time an algorithm changes. But it does mean pushing for more transparency and accountability. It means questioning the idea that “personalized content” is always harmless. And it means realizing that the systems governing our digital lives are not neutral—they’re made, maintained, and rearranged by humans with commercial purposes.

We as users cannot fix it, but we can pay attention, support those creators who stand against the system, and push for stronger platform regulation in the interest of the greater good, rather than an individual’s private goods. After all, if we value a place where everyone can have a say in their online lives regardless of how loud theirs is the loudest coming from an algorithm muttering “keep watching” every few ads.

Reference

- Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

- Lupton, D. (2016). The quantified self: A sociology of self-tracking. Polity.

- Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346.

- Musiani, F. (2013). Governance by algorithms. Internet Policy Review, 2(3), 1–8.

- Neff, G., & Nafus, D. (2016). Self-tracking. MIT Press.

- World Economic Forum. (2011). Personal data: The emergence of a new asset class. World Economic Forum.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment