You may have experienced this scenario: you are chatting with a stranger on a social media platform and casually ask “where are you?” But on the Chinese Internet, this question becomes redundant because your location is already automatically displayed.

In mid-2022, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) issued a new regulation requiring platforms to display users’ IP location to safeguard public interests and information authenticity. Chinese social platforms such as Weibo, Douyin and Rednote have responded and started to display users’ IP location by default. This is not an optional feature for users, as the platform does not need to obtain users’ consent to disclose their IP location (Liu, 2023). That is to say, every word spoken by users on the network, every account created, has an “address signature.” This sounds like a bit of transparency to the anonymized network, which can maintain the order of the Internet, but meanwhile, it also makes a subtle change in China’s cyberspace: users are no longer “some netizens” who have never met, but “people from somewhere.”

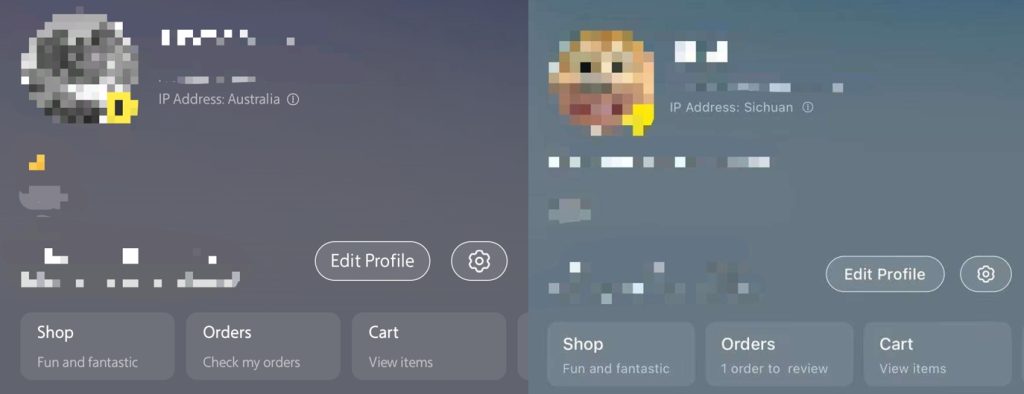

The users’ home pages show the IP address

This not only changes users’ expression, but also their sense of identity in the online world. Because your identity is no longer just a representation of yourself, instead, your speech and opinions become a projection of “geographical location, belonging place” and even “standpoint.”

As societies adapt to the digital age, the boundaries between public and private space in social platforms are increasingly blurred (Suzor, 2019), we must ask whether this is really just “information transparency”? Or a more systematic and robust form of digital surveillance that is quietly taking effect? What is the position of our privacy and digital rights?

“Do you want to be seen?”

It is undeniable that the display of IP location has made cyberspace more and more like real society, and users are no longer in a real anonymous state on social media, but also imperceptibly strengthen the labeling and prejudice of identity.

Many are “self-censoring” – worried that “what they say represents the whole region” and “others will be misunderstood because of their IP location”, worried about “being labeled”, and even subjected to cyberbullying and cyber manhunt. While this kind of self-censorship is not new, the forced disclosure of IP location has further reinforced this pressure, and the original diverse voice is gradually replaced by “cautious” and “homogenous”.

All of this, without asking users’ opinion, completely bypassing their right to choose. They are automatically disclosed and classified geographically, which is an “established fact” promoted by regulators and platforms.

Perhaps, before the goal of “safer and more harmonious” cyberspace arrives, making user information “more transparent” comes first. Privacy is no longer just about “what to hide,” but “who decides when and how to expose us.”

The question is, before all this began, was anyone ever asked:

“Do you want to be seen?”

Who Makes the Rules?

So, who decides that users must be “seen”?

Obviously, the answer is, as we mentioned at the beginning of this article: the state sets the rules, and the platforms enforce them.

In fact, disclosing IP location is not an isolated policy of China, but a process of its progressive digital governance.

- 2015: The CAC issued the “Internet User Account Name Management Provisions”, proposing the principle of “Real-name registration behind the scenes, voluntary disclosure up front”(Article 5), requiring Internet users to register an account after real identity information authentication.

- 2017: Internet Forum Community Service Management Provisions came into effect, which stipulates that “if users do not provide real identity information, network operators shall not provide relevant services for them (Article 8).” This is widely seen as a sign that China is fully implementing the online real-name system.

- 2022: Internet User Account Information Management Provisions further required the platform to display IP location forcibly (Articles 12, 13). After that, Internet celebrities with a certain number of followers must display their real names in the profile interface.

The celebrity’s profile shows his real name and IP location

The governance logic at the heart of this series of measures is clear:

So that every voice can have a corresponding “real identity”, so that every speech can be traced to the source.

It’s a top-down governance model where users don’t really participate.

- You can’t choose whether or not to display your IP location.

- You can’t refuse to bind the account to real-name information such as mobile phone and ID card.

- Similarly, you can’t refuse the platform agreement – otherwise you won’t be able to use the services it provides.

This exposes a deeper question: Are digital policies and governance taking into account users’ privacy and digital rights?

All of this is based on order, security and accountability, but in practice, users’ space for expression is also potentially compressed. The cost of free speech is greatly increased, and the possibility of anonymous expression and easy communication is reduced.

There seems to be no room for opposition to a digital policy based on the “public interest.” This governance mechanism ignores the diversity and complexity of users and the digital world. In this game of privacy versus surveillance, users’ rights are being marginalized.

Perhaps we should revisit such digital governance, which is not a neutral deployment, but a hybrid of technological governance and authoritarianism.

Right or Duty?

Proponents of disclosing IP location argue that it is a beneficial digital policy. It can enhance online accountability, combat rumors, clean up bad information and improve credibility. However, in this logic, privacy no longer seems to be users’ right, but becomes a responsibility – you must first hand over personal information to qualify as “trusted.”

Before that, privacy was a right, and the choice of whether or not personal information was made public depended on the user, who could decide whether to disclose, how much to disclose, and to whom. Because of this, there is the privacy paradox – on social media, users are concerned about privacy security on the one hand, and actively disclose personal private information on the other hand – because the choice is in their hands (Kokolakis, 2017).

But now, with the forced disclosure of IP location, this choice is being taken away. Privacy seems to have become a duty, and disclosure an obligation to obey rules and disclose information in exchange for “trusted speaking” before entering the digital society and having digital rights.

Privacy is a “passport” you have to pay. Users have to accept being seen before they can speak.

At the same time, problems related to this policy have also emerged.

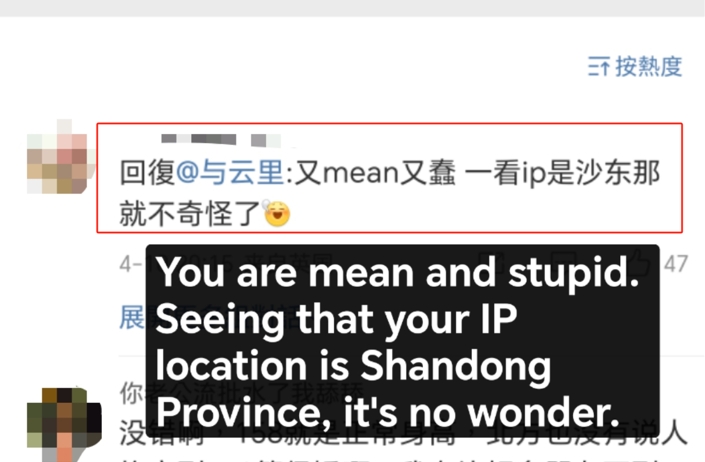

Regional discrimination

Regional discrimination is a common form of cyberbullying and hate speech in China. The disclosure of IP location amplifies the risk of discrimination on the Internet based on location alone, making it easier for attacks on stereotypes to find targets and discourage people from speaking out. Because an individual’s opinion can be perceived as representing the majority of his/her IP location, it leads to people attacking each other’s IP location instead of having a calm, rational debate. And this may further increase the potential risks of cyber manhunt (Liu et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2023).

If the IP location is shown as a province of China, some people will make judgments and attributions directly based on geography.

If the IP location is shown as other countries, the problem can be more complicated. Some people will therefore be questioned whether they are “foreign forces” or “have other purposes”.

Mechanisms that are supposed to protect users have instead become tools to amplify bigotry and hatred. Many people have been scolded because of IP location; being attacked for geo-tagging; because it is not in the “mainstream public opinion zone”, it is suspected of “ulterior motives”. Such location-based judgments can exacerbate discrimination, silence voices, and discourage participation. Rules designed to purify the web have instead raised new prejudices and rivalries.

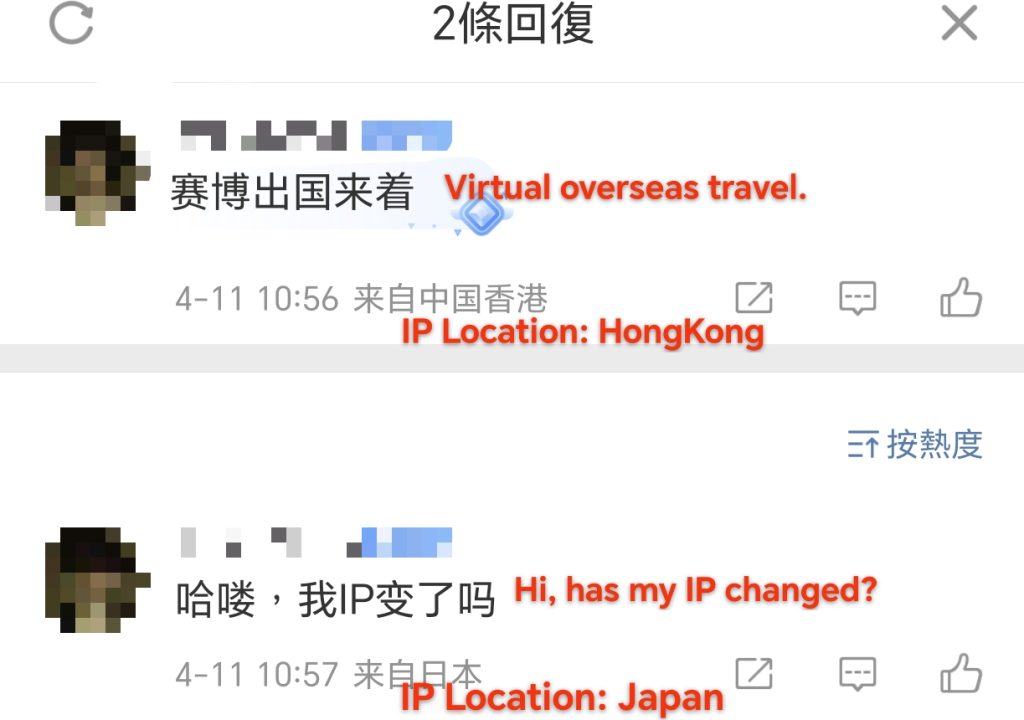

Counterfeit IP and grey industries

In addition, the grey industry of modifying IP location and setting up virtual IP is also quietly growing. For a certain amount of money, users can use a VPN or other IP proxy tool to change their IP address on a social platform, either to protect their privacy or to evade surveillance (Figure 5). These actions are more likely to introduce a new risk: using a low-quality VPN or third-party tool may expose users to a larger data breach. Ironically, in order to be “transparent,” the platform pushes the IP location to be displayed; but users are forced to “disguise” for security. The policy intended to clean up the online environment has ended up giving rise to new forms of digital identity manipulation and deception.

A user use the tool to quickly change the IP location

The mechanism that was supposed to protect you turned out to be the tool that limited you. We have to think:

When “privacy” is no longer a right you can claim, but an obligation you must surrender, what are we really losing?

Who is Going to Empower?

There is always a game between digital governance and users’ privacy and digital rights.

The chilling effect suggests that surveillance is a political disincentive that prevents people from exercising their right to freedom of expression due to fear of risk or pressure from authority (Zhu, 2024). When the disclosure of IP location becomes a mandatory rule, the expression of users is in a difficult trade-off between “self-protection” and “being seen”. The anonymity of cyberspace is gradually deteriorating, and personal privacy is gradually being violated. Surveillance is not abstract; it is changing the way we behave. So the question is not just “whether IP location should be disclosed”, but, in the process of formulating digital policies and conducting digital governance:

Who decides what privacy and security are? Where are their boundaries? Who really represents the interests of users? And who can empower users?

Some regions around the world have attempted to emphasize user initiative on privacy and rights in digital policies and governance. For example, the European Union’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) specifies the rights of users as digital subjects:

- Users must explicitly consent to the collection and use of data and have the right to withdraw their consent at any time.

- Users have the right to delete, modify, migrate their data and to object to the processing of any personal data relating to their particular circumstances.

General Data Protection Regulation

This mechanism emphasizes a fundamental principle: the user has the right to choose. “Where are you?” under the GDPR framework is a question you can answer, it’s not a label you have to disclose.

Empowerment is not a slogan, but means that users can have a respected voice and controlled choices in the formation of rules, disclosure of information, and definition of rights.

If we can’t decide how we’re seen online, how can we really be digital citizens?

Maybe, in this game, we can find a balance.

An individual’s relationship with privacy is largely determined by their environment and social dynamics (Marwick & Boyd, 2018). In China’s digital context today, we can still ask this crucial question:

Why can’t I decide whether to let people know where I am?

Words in the end

Game and balance

In today’s digital world, where new digital technologies are closely linked to economic power relations and governmental and regulatory structures, individual rights also form a central issue in digital policy. Digital policy is not simply a choice between freedom and non-freedom, but rather a balancing of multiple values, interests, and goals to construct different governance models (Karppinen, 2017). For Chinese Internet users, the disclosure of IP location is not only a line of gray print on a social platform, but also reflects a deeper question:

Can users have real and concrete rights in digital governance?

Of course, this is not a problem unique to China, and there is a pervasive tendency to deprive already fragile digital rights in the name of security, “trust,” or anti-corruption, even when those policies are oriented toward legitimate, rational goals (Buttarelli, 2017). If there is no room for negotiation in such a system, consent becomes a forced act, and privacy becomes a conditional privilege. Therefore, while the legitimacy of digital governance should be determined by its purpose, it should also consider the digital rights of users. We are not against technology, and we are not against governance. Instead, as we get used to the “must consent”, we ask for another possibility:

Do we have any alternative to the Terms and Privacy Policy?

The declaration alone does not mean that digital rights can be realized in practice (Karppinen, 2017), and how to find the optimal solution between privacy, security, digital rights and digital policies, and find the balance between governance and empowerment, on the premise of respecting users’ privacy and digital rights, rather than at the expense of them, will remain an ongoing issue.

References

BBC News Chinese. (2017, June 1). 全面实名后还有隐私吗——中国网民看”网络实名制” (Will there be privacy after comprehensive real-name system? – Chinese netizens see “online real-name system”).https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/chinese-news-40056223

Buttarelli, G. Privacy matters: updating human rights for the digital society. Health Technol. 7, 325–328 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-017-0198-y

Central Government of People’s Republic of China. (2022, June 27). Internet User Account Information Management Provisions. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-06/28/content_5698179.htm

Cyberspace Administration of China. (2017, August 25). Internet Forum Community Service Management Provisions. https://www.cac.gov.cn/2017-08/25/c_1121541921.htm

Cyberspace Administration of China. (2015, February 4). Internet User Account Name Management Provisions. https://www.cac.gov.cn/2015-02/04/c_1114246561.htm?nsukey=YiepddNs2hikwN1XLTIqA+r7wdieRk3Y59fXi/EUUde

European Parliament and Council of the European Union (Ed.). (2016). General Data Protection Regulation GDPR. https://gdpr-info.eu/

Fang, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2022, May 16). 揭开”IP代理”灰色产业链:16元包月”环游”全国?小心泄露个人隐私 (Reveal the “IP agent” grey industry chain: 16 yuan monthly “travel” around the country? Be careful about giving away your privacy). Shenzhen Evening News. https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20220516A05PGY00

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

Kokolakis, S. (2017). Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon. Computers & security, 64, 122-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002

Liu, S. (2023, November, 2). 中国互联网平台实施前台实名制 (China’s Internet platforms implement real-name system at the front).联合早报(LIANHE ZAOBAO). https://www.zaobao.com.sg/news/china/story20231101-1447253

Liu, Y. C. (2023). Analysis of the Legality of the Platform Disclosing the User IP Territory. The Law, 11(5), 4313-4319. https://doi.org/10.12677/OJLS.2023.115612

Liu, Y. L., Wu, Y., Li, C., Song, C., & Hsu, W. Y. (2024). Does displaying one’s IP location influence users’ privacy behavior on social media? Evidence from China’s Weibo. Telecommunications Policy, 48(5), 102759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2024.102759.

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International journal of communication [Online], 1157+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A561120196/AONE?u=usyd&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=3df64beb

Ma, Y., Zhou, Q., Tag, B., Sarsenbayeva, Z., Knibbe, J., & Goncalves, J. (2023). “Hello, fellow villager!”: Perceptions and impact of displaying users’ locations on weibo. In IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 511-532). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42286-7_29

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules? In Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern our Digital Lives (pp. 10–24). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Zhu, Y. (2024). Privacy cynicism and diminishing utility of state surveillance: A natural experiment of mandatory location disclosure on China’s Weibo. Big Data & Society, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517241242450

Be the first to comment