More and more people are drawn to the idea of flexible work—no clocking in, no office cubicles, no boss watching over your shoulder. All it takes is a car and a mobile app, and you can become a rideshare driver. It sounds like the perfect blend of freedom and dignity. But the reality is far less ideal.

Many drivers soon discover that this so-called “freedom to accept orders” is in fact a relentless, exhausting battle dictated by algorithmic control. As one rideshare driver from China bluntly put it: “I don’t dare take breaks. I’m afraid of missing assignments. It’s like the whole person is led and controlled by the app through the day. (Zhihu, 2024)”. This isn’t an exaggeration—it’s the daily reality for millions of rideshare drivers across China (Wangshu, 2021).

The Rise of Rideshare Platforms

From phone bookings and hailing taxis on the roadside to tapping a screen and getting picked up within minutes, rideshare platforms have fundamentally transformed how we move through cities. Apps like Didi, Gaode, and T3 Mobility (China’s online ride-hailing platform) have significantly improved urban transport efficiency and truly delivered on the promise of “anytime, anywhere” travel.

As of June 2024, China’s ride-hailing sector had reached 530 million users. In that year, the annual orders reached 11 billion (MoonFox, 2024). Rideshare services have become a foundational part of daily urban life, much like public utilities.

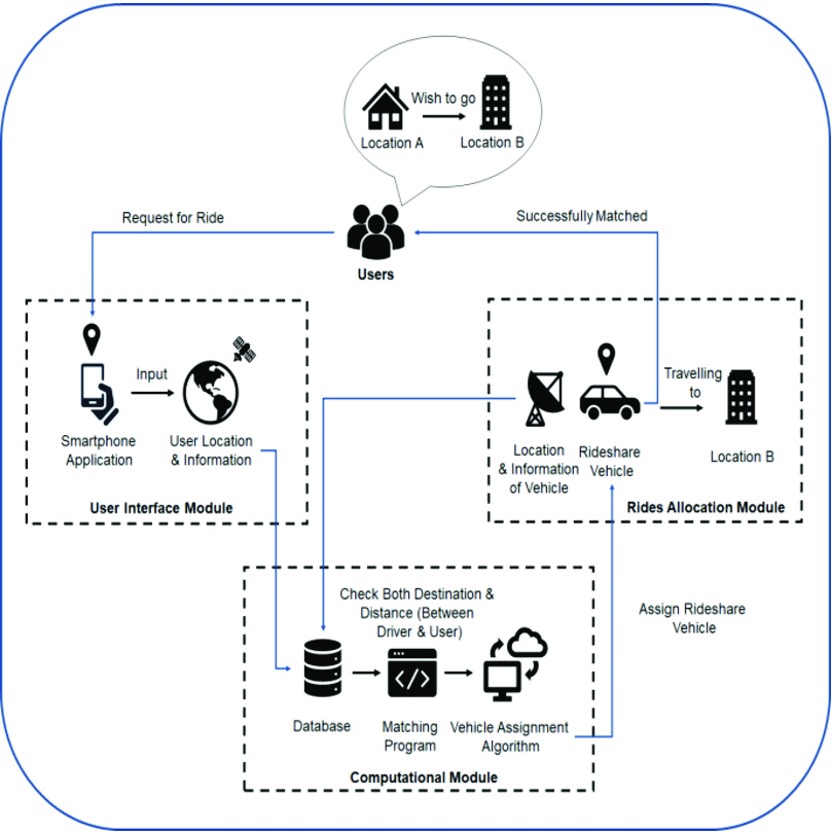

But behind what seems like a simple ride-hailing service lies a shockingly complex technical system (as Figure 3 shows). As soon as you input your destination, the platform takes into account a wide range of real-time factors: rider and driver locations, traffic congestion, driver availability, weather conditions, public holidays and so on. It uses all this to generate the most efficient order match—usually within seconds. This isn’t handled by customer service reps watching from behind the scenes—it’s entirely managed by algorithms that read your behavior, anticipate your needs, and dispatch resources across the city. And we are going to explore this system critically in this post.

Behind the platform’s seemingly friendly interface is a micro-governance system driven almost entirely by algorithms. This phenomenon is referred to as “Algorithmic Governance”—a form of rule-setting and behavior coordination controlled by computational systems. Algorithmic governance refers to a system in which computational processes dominate how rules are made and behaviors are coordinated. It doesn’t merely carry out pre-set human instructions—it continuously analyzes data and autonomously evolves structural logics that shape how users act and interact (Flew, 2021). Simply put, it’s a form of governance in which algorithms replace human oversight, making decisions, allocating resources, and enforcing rewards or penalties without any human in the loop.

From Managing Traffic to Managing People: The Power Behind Platform Algorithms Governance

As intermediaries between passengers and drivers, rideshare platforms use data analytics to automate the entire process—matching supply and demand, optimizing routes, dynamically adjusting prices, assigning orders, collecting feedback, and setting incentive schemes. For instance, Didi’s AI system, known as the “DiDi Brain,” performs a global supply and demand analysis every two seconds to dynamically match passengers with drivers in real time (Tencent Cloud, 2022). It can also forecast ride demand about 15 minutes in advance with an accuracy rate of 85% in specific regions (Qin, et al., 2020). There’s no denying the efficiency of this system.

Through algorithmic governance, platforms have essentially installed a kind of “automated nervous system” into the urban transport grid. They orchestrate a city’s traffic flow in real time, backed by a vast, invisible workforce of digitized labor responding to data-driven commands. But herein lies the problem. The most intelligent feature of algorithmic systems is also the most dangerous characteristic. In this system, it’s not just the traffic being managed by algorithms—it’s also the people.

Whether you accept rides frequently, how quickly you pick up passengers, if you take detours, your customer ratings, your complaint record—everything is logged, quantified, and evaluated. Drivers have no control over which orders they receive, and they’re rarely told how their performance is assessed. The platform presents it simply as “a system decision,” yet offers no explanation of how that decision is made, which is the true logic of algorithmic governance. The algorithm is no longer a tool—it has become power itself.

Meanwhile, passengers aren’t exactly “free” either. If you frequently use the app, have a frequent payment history, and maintain high credit scores, the algorithm may label you a “high-value user”—which sounds flattering until you realize you’re being charged more. Same time, same route, but new users get cheaper rides, while loyal customers “enjoy” algorithmically inflated prices. This is precisely what scholar Shoshana Zuboff calls Surveillance Capitalism: a platform economy where the goal is no longer just to serve users, but to continuously monitor individual behavior in order to build data-driven prediction systems. These systems are not passive; they are engineered to guide, reshape, and even control user actions. Every interaction—how often you hail a ride, how you respond to pricing, how likely you are to file complaints—is captured, analyzed, and looped back into the algorithm to maximize the platform’s commercial interests (Zuboff, 2019).

And this surveillance doesn’t just apply to passengers—it’s even more intense for drivers. From the moment they’re active on the platform, drivers enter a fully monitored environment. The system tracks how fast they accept orders, how long they take to depart, their route choices, service ratings, cancellation reasons—even how long they take breaks. This data builds a behavioral profile for each driver, which the platform uses to decide whether they’re “reliable,” whether they deserve priority orders, and whether they qualify for bonuses. This isn’t performance management in the traditional sense. It’s a data-driven system of behavioral conditioning, where surveillance fuels incentives, and incentives shape how people work. It’s a silent, algorithmic power that rewires labor without ever having to say a word.

Taken together, it becomes clear that the AI systems deployed on these ride-hailing platforms are not merely technological tools—they are deeply extractive systems (Crawford, 2021). Platforms extract labor and risk from drivers, behavioral data and payment intent from passengers, and even public infrastructure and time from the city itself—all ultimately to serve their commercial interests.

Beneath the Algorithm: Trapped, Exploited, and Pushed to Resist

Within the algorithm-driven rideshare system, drivers are undeniably its core operators. Ironically, they are also the most exploited and disempowered group within it.

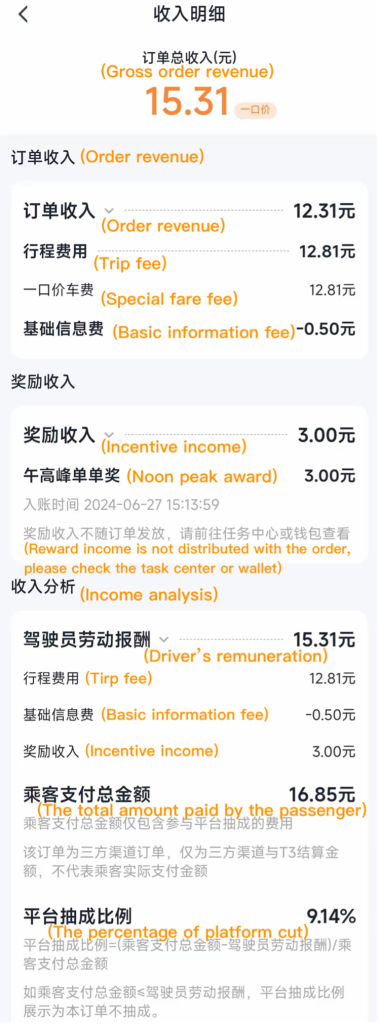

Platforms roll out so-called “incentive policies” that sound like generous reward schemes, but in reality, function as subtle pressure mechanisms.

Want to earn more? Then you must hit the platform’s daily performance targets: for example, complete 30 rides to qualify for a bonus. Behind these targets lie grueling workdays that stretch well past 10 hours (Zhihu contributors, 2023).

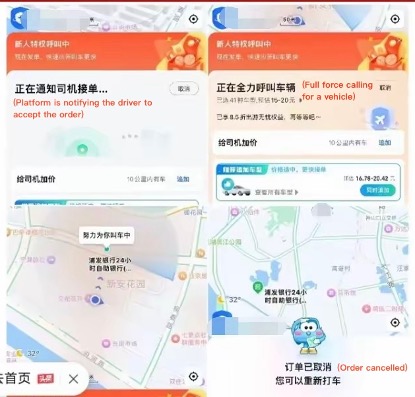

“If you ever slow down, skip an order, or cancel one, the system will start assigning you the farthest rides, the lowest fares—or worse, no orders at all.”

From one hailing driver words in China (Zhihu contributors, 2023)

What’s even more frustrating is that drivers’ rights are also constrained by the platform’s passenger rating system. Unlike Uber—which features a mutual ratingmechanism between passengers and drivers—most Chinese platforms adopt a one-way evaluation system. This means that if a passenger is dissatisfied—or even deliberately leaves a bad rating—the driver’s access to future orders will likely suffer. They may receive fewer assignments, or be left with long-distance rides that offer minimal subsidies. And the real issue lies in the appeal process: drivers often find themselves facing cold, automated AI customer service that delivers templated responses without providing any meaningful resolution. It doesn’t feel like working for a human boss—it feels like reporting to a black-box system: a system that sets the rules, enforces the punishments, and never explains why it does what it does. Such conditions intensify the information asymmetry between drivers and platforms, gradually pushing workers into a more isolated and powerless state. As Parent-Rocheleau and Parker (2022) argue, algorithmic management deprives gig workers of control over their schedules, income structure, and even their ability to advocate for their rights.

However, as the pressure intensified, anger and resistance finally reached a breaking point. In 2022, Didi introduced its “flat-rate” and “special fare” schemes, which effectively reduced driver earnings per ride in exchange for boosting passenger volume. The move triggered long-simmering frustration among drivers. In cities like Hefei and Hangzhou, large numbers of drivers returned their leased vehicles to rental companies and collectively refused to go online on the platform during peak hours—causing widespread ride shortages and transportation chaos.

Industry experts were quick to criticize the platforms: “For the ride-hailing sector to develop in a healthy way, platforms must balance the interests of both drivers and passengers. Favoring one side at the expense of the other is not a sustainable solution.” (Zhihu contributors, 2024)

Drivers’ resistance was not a rejection of technology, but a challenge to the power structures embedded within it. Through their small yet determined acts, drivers have exposed the limits and risks of the current model of algorithmic governance—and compelled us to confront a critical question:

How should we govern the increasingly powerful platforms and algorithms that shape our everyday lives?

What Kind of Algorithmic Governance Do We Need?

In 2022, the Ministry of Transport launched a campaign called the “Sunshine Commission Initiative,” requiring platforms to disclose how fares are calculated and what proportion of revenue goes to drivers. Yet these measures remain focused on transparency of outcomes, without truly addressing the core issues of transparency in how algorithms operate and whether their decisions can be questioned.

By contrast, international frameworks have gone further, emphasizing transparency of the process and the right to human intervention.

For example, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) clearly states that when an automated decision has a significant impact on an individual’s life—such as being banned from a platform, having access restricted, or being subjected to price discrimination—users have the right to be informed, to opt out of fully automated decision-making, and to request human intervention (ICO, 2024). In the context of ride-hailing, this means creating systems that are more humane and transparent—so that passengers and drivers are not subjected to algorithmic decisions without their knowledge or consent. Instead, platforms should offer explainability, accountability, and channels for human support, especially when drivers are unfairly penalized by opaque algorithms that affect their income.

And on the labor rights front, a 2021 court in Amsterdam ruled that Uber drivers must be classified as employees rather than independent contractors. This means the platform has to assume full employer responsibilities—including guaranteeing minimum wages, respecting collective bargaining rights, and regulating working hours (Deutsch & Sterling, 2021).

Algorithms are not neutral—they are instruments of governance and must themselves be governed. What we truly need is a governance framework that has the courage to constrain platform power, and that empowers both drivers and consumers with the rights to know, to participate, and to challenge. To be specific:

- We need a system that no longer allows algorithms to escape accountability. Platforms must not continue to hide behind the excuse of “automatic decision-making,” using it to justify commercial strategies as if they were neutral technical judgments.

- We need a system whererules are not dictated unilaterally by platforms, but are subject to public negotiation, with workers and users actively participating in the design, adjustment, and oversight of algorithmic systems.

- We need a system that returns algorithms to their rightful place—as tools, not as masters.

As Kate Crawford (2021) writes in The Atlas of AI, artificial intelligence is no longer just a technical system—it has become an industrial infrastructure, a mechanism of data extraction, labor control, and profit generation. If left unchecked, it could become the feudal logic of our digital age.

Conclusion

As we’ve explored throughout this piece, the so-called ideals of “flexible work” and “freedom to drive” often amount to little more than technological oppression wrapped in softer language.

The tremendous success of platform economies forces us to acknowledge the power of technology in improving efficiency and connecting resources. But we must also stay vigilant: efficiency must not come at the expense of ethical responsibility, and commercial logic cannot be allowed to replace the need for public accountability.

The advancement of technology should not be a one-sided race, but a negotiated journey shared with the social contract. Governing algorithms is not about stifling innovation—it is about safeguarding human dignity, freedom, and fundamental rights. Platforms must return to their role as service providers, and algorithms must return to their rightful place as tools. Only then can drivers, passengers, and everyday users feel a sense of security and agency in a data-driven world. This is not only the ethical bottom line of technology—it is also a realization of what innovation was originally meant to do: to serve the public good.

Reference

Bakibillah, A. S. M., Paw, Y. F., Kamal, M. A. S., Susilawati, S., & Tan, C. P. (2021). An incentive based dynamic ride-sharing system for smart cities. Smart Cities, 4(2), 532–547. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4020028

China Daily. (2021, September). Ride-hailing companies told to obey rules. Chinadaily.Com.Cn; Luo wangshu. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202109/03/WS61316f29a310efa1bd66d082.html

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.pp.1-21.

Deutsch, A., & Sterling, T. (2021, September 13). Uber drivers are employees, not contractors, says Dutch court. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/dutch-court-rules-uber-drivers-are-employees-not-contractors-newspaper-2021-09-13/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 79–86.

MoonFox. (2024). Insights into the development of the ride-hailing industry in 2024. Retrieved from https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202501141641912513_1.pdf

ICO (Information Commissioner’s Office). (2024, December 11). What are the accountability and governance implications of AI? ICO. https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/artificial-intelligence/guidance-on-ai-and-data-protection/what-are-the-accountability-and-governance-implications-of-ai/

Parent-Rocheleau, X., & Parker, S. K. (2022). Algorithms as work designers: How algorithmic management influences the design of jobs. Human Resource Management Review, 32(3), 100838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2021.100838

Qin, Z. (Tony), Tang, X., Jiao, Y., Zhang, F., Xu, Z., Zhu, H., & Ye, J. (2020). Ride-Hailing order dispatching at DiDi via reinforcement learning. INFORMS Journal on Applied Analytics, 50(5), 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.2020.1047

Tencent Cloud. (2022). Disassemble the Didi brain Ye Jieping talks about algorithm technology in the field of travel. Tecent Cloud; Tencent cloud developer community. https://cloud.tencent.com/developer/article/2078926?from=15425

Wangshu, L. (2021). Ride-hailing companies told to obey rules. Retrieved from China Daily: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202109/03/WS61316f29a310efa1bd66d082.html

Zhihu contributors. (2023, October 10). 6.57 million ride-hailing drivers trapped by algorithms, with no way out. Zhihu. https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/680999464

Zhihu contributors. (2024, March 28). Reflections on the ride-hailing industry from a driver’s perspective. Zhihu. https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/704188034

Zhihu contributors. (2024, October 18). Unity is strength! A ride-hailing platform in one region was boycotted by drivers, leaving passengers unable to get a ride at all. Zhihu. https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/1850750590

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment