In July 2022, a 23-year-old Chinese girl named Linghua Zheng posted a photo on the social platform Rednote. In the photo, Zheng, with beautiful pink hair and a smile, with the graduate admission letter in one hand and the ailing grandfather’s hand in the other, telling him the good news. In the post, she wanted to convey her kinship with her grandfather, her thankfulness to him, and her pride in herself. However, the Internet responded to her joy in a cruel way — the post and photo went viral quickly, and strangers flooded her comments, mocking her pink hair, shaming, attacking and spreading rumors about her, calling her a “nightclub girl” and implying that she was “morally corrupt”, and even fabricating in the comments that she had an “improper relationship” with her grandfather. Photos of her warm relationship with her grandfather were maliciously interpreted. The pink hair she dyed to celebrate her success was also seen as a symbol of ” dissolute”, and Zheng herself became the target of an online hate speech.

Although Linghua Zheng has maintained a positive attitude against the negative comments from the Internet, unfortunately, six months after she going through the online violence, she was diagnosed with depression and her physical and mental condition continued to deteriorate, finally, she committed suicide at home on January 23, 2023.

Her passing is truly heartbreaking , but it is also worth thinking about: How do we define “hate speech”? Why SHE suffering this? Are platforms amplifying this kind of violence? And how should we do to deal with these tragedies of the digital age?

Pink Hair? Why Attack Pink Hair?

Although as a poster, Linghua Zheng is not a public figure, nor did she make provocative remarks. She is just an ordinary female college student, expressing the joy of her life in her own way. But why can her pink hair become the focus of online attacks?

Let’s focus on some more conservative areas in China, in their contexts and perceptions, hair dyeing, is often seen as an “immoral” behavior. Dyeing one’s hair in “uncommon” colors such as red, pink or green is often equated with “frivolousness” and “ unruliness”. Perhaps Zheng’s choice of hair color challenged the stereotype of a “normal woman”, so they gave her the title of a “woman of affairs”. In this sense, Zheng ‘s pink hair is no longer just her personal aesthetic choice but rather a symbol of the so-called “bad woman”.

What Is The Real Definition Of Hate Speech?

Many people mistake hate speech for “name-calling” or “threats.” .But in reality, its definition is far more complicated than that.

As discussed by Parekh (2012),hate speech is language that is stigmatizing, humiliating, or inflammatory against a specific social group (such as gender, race, religion, etc.), which causes emotional harm and furthermore excludes that specific social group from the public sphere. (Flew, 2021, p. 115).Not only can hate speech be verbally abusive, but it can also be sarcastic, humorous , or even exist under the guise of “traditional morality.”

Some studies have pointed out that certain platforms, such as Facebook, only pay attention to whether hate speech contains offensive words. In fact, many seemingly “mild” expressions are just as harmful. Although these words do not contain swear words, yet use “gentle wording” to deny the existence and degrade the identity of minority groups, which is more harmful (Aim Sinpeng,2021, P12).

However, in Zheng’s case, we can find that some attackers did not directly use rude language, but used “social morality” to discipline her, making her a “negative model” of “unfilial behavior” ,remarking that she was only “pretending to be kind”. Hate speech is also destructive because the attacked person’s right and space to participate in public life are stripped away(Flew, 2021,p. 117).

Thus, it can be seen that the definition of hate speech is actually very subtle. It can either be clear or appear in an undefended form, thereby causing lasting and difficult damage to the attacked person.

There Is More Than One Killer: Algorithms Have Become Accomplices

Zheng’s post went viral not because of the warmth of familial love or inspirational story that most people assume, but simply because it had received vitriol that incited scorn against her.

Social platforms algorithms recommend and circulate content from specific users, with the basic premise being that the more engagement generated by a person’s post, the more recommended they are to a wider audience. Put simply, the more “controversial” your content, the greater potential to go viral. This is in line with the concept of “toxic technocultures”, which means that platform mechanisms have already implicitly encouraged a digital culture based on shame and novelty (Massanari, 2015, p. 334).Similarly, Matamoros-Fernandez et. proposed the concept of “platformed racism” in their research, claiming that platforms are not neutral, but promote the mechanism of hate speech spreading against specific groups (Matamoros-Fernandez, 2017, p.933).

Looking at Zheng’s case, it was also the irrationality of the algorithm that further fueled the wave of online hate speech against her: a few hateful comments attracted more hostile users, leading to an avalanche of malicious remarks that eventually overwhelmed Linghua’s strong and positive mindset.

how does sexualized humiliation become the norm of network attacks?

It can be found that when Zheng’s pink hair image in the photo was attacked, it soon evolved a more vicious rumor: she had an “improper relationship” with the elderly man in the hospital bed (her grandfather). This groundless rumor is completely out of the malicious association of strangers online. In the photo, she just shows her grandfather her admission letter and holds his hand with smile on her face. It was nothing more than a simple, heartwarming moment, yet for some reason, certain people distorted it through a dirty lens, forcefully fabricating the narrative that Zheng Linghua led a promiscuous private life.

These sexually suggestive or humiliating comments were not random outbursts, but rather the result of a long-established “instincts” influenced by the mechanism of “sexualized shaming” that has been learned and spread in digital culture for a long time. It unconditionally links women’s bodies and emotional expressions to ‘sex’, regardless of their original intent—on the internet, such expressions are often interpreted as acts of ‘flirt’, ‘display’, or ‘impropriety’.

In Doring and Mohseni’s research, through their analysis of failed videos on YouTube, found that even if women appeared in the most common images, they were prone to “gendered shaming” comments, such as “sexy” and “deserved”, based on their appearance or gender (Doring &Mohseni, 2019, p. 260). Such language may seem to be teasing and “joking”, but its essence is to deprive women of their subjectivity—a violent reminder that “you should not be in public space like this”.

Zheng’s “stigmatization” is not because she has really done anything wrong, but simply because her existence is too “eye-catching”–her hair color is too bright and her achievements are too excellent. Her existence is considered “provocative” by some people, so she must be “corrected” and “punished”. In such a digital public space, women who “do not conform” are either understood or “hunted” .

the real psychological damage of online hate speech

The harm of Internet violence is never just from words. It doesn’t become harmless just because there’s no swear words in the comments, or just because the violent attacker is behind a screen. Zheng was unfortunately diagnosed with depression shortly after being bombarded with online comments. According to the South China Morning Post, she suffered from chronic insomnia, loss of appetite and depression, and could not even study and live normally. After a period of recovery, Linghua committed suicide at the age of 23 in early 2023 due to the repeated deterioration of her condition, thought she was being active towards her treatment throughout her illness (SCMP, 2023).

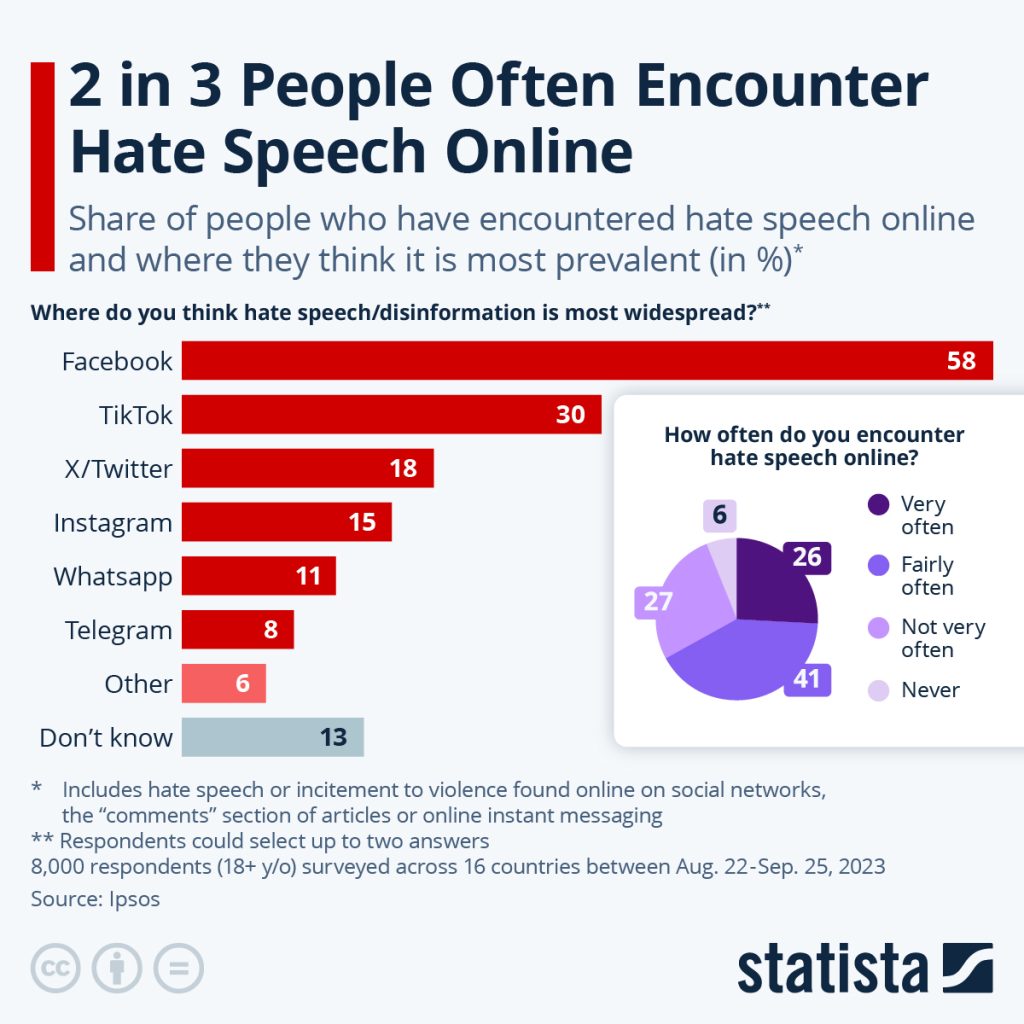

source: (2024, October 21). 2 in 3 people often encounteh online. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/33299/online-hate-speech-encounter

Hate speech is not only verbal violence, but also a form of psychological harm that can continuously erode the dignity of the individual, create long-term anxiety for the victim, self-doubt and social fear (Aim Sinpeng, 2021, p.6). This erosion, though quiet, can be enough to alter course of a life that might have otherwise been beautiful .Hate speech does more harm than that — it can not only silence individuals, but also deprive vulnerable members of a community of the courage to speak out and participate (Flew,2021,p. 117). When a young woman is shamed to death for simply having an unnatural hair color and displaying success, many shining people like her, who could express themselves generously, may choose to remain silent for fear of becoming the next target of hate speech.

Zheng’s leaving was not “too fragile”. She was pushed to the abyss of despair bit by bit by the invisible hand of those who repeatedly stigmatized her and the indifference of the platform. Her death reveals to us a cruel fact: in the seemingly free digital space, some people are not even allowed to express “joy”.

Why do platform moderation systems so often ‘fail’

Most platforms claim that they have community norms and are against hate speech, but in practice, their moderation mechanisms often end up being little more than window dressing — too slow or ineffective. Many victims find that no matter how many times they report or submit evidence to the platform, their response is always “this content does not violate community rules.”

Some studies have pointed out that Facebook faces huge challenges in content moderation in the Asia-Pacific region, especially in the three areas of language recognition, cultural context understanding and human moderation. Sinpeng et cite a number of studies in their report, pointing out that Facebook’s automated system covers less than 40 languages, resulting in many regions where languages and dialects are not recognized at all, and the reach and speed of human moderation is limited (Sinpeng, 2021, p. 3).

Flew et (2021) further pointed out that the automatic content recognition systems of most platforms can recognize almost only the most explicit offensive speech. Forms of attack such as “gendered”, “moralized” or “implied”, such as “How dare she post when she looks like this?” or “ Don’t you think she and her grandpa have a weird relationship? “, although this kind of discourse is not rude, it is full of sexism and humiliation, but is often considered as “safe content” by the platform algorithm. The result is that users who are truly violated continue to report, but there is always no effective response.

When their repeated attempts at justice are met with silence and neglect, they will become “reporting fatigue”—disappointed and powerless to the point of giving up on defending their rights(Sinpeng et al., 2021, p. 38) . If this continues, not only will individuals suffer, but entire communities will experience a “spiral of silence”: the voices that should be protected will be silenced, and the public space will be filled with the voices of the attackers.

Zheng is one of the tragic victims of this process. She also tried to defend herself, responded to malicious comments, and tried to protect herself legally by contacting lawyers for evidence collection, but the platform did not provide justice for her, and the process of Internet evidence collection was extremely difficult. It is not that she did not resist, but that her resistance was never cared about by the platforms.

What can We do?

Zheng’s death is not the direct result of a single bad comment, but the result of a systemic problem: The algorithm’s cold logic, cultural prejudice, and the platform’s failure of inaction. Her story is not only a typical example of cyberbullying, but also a mirror of the digital injustices of our age. Change requires an awareness of the real harm of hate speech, which not only destroys individuals ,but also erodes fairness and democracy in public life (Flew, 2021, p. 117).If we continue to be silent about hate speech, we are gradually making room for the normalization of violence of all kinds.

Figure 3 Illustration of a person screaming with bullets flying out of the mouth as a metaphor for hate speech and aggression. [Stockfoto / Getty Images]

Source:Datta, A. (2025, February 22). Hate speech failures by Meta and X undermine German election [Illustration]. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/tech/news/hate-speech-failures-by-meta-and-x-undermine-german-election/

Zheng used to be just an excellent girl who wanted to share her joy and successful experience with everyone, and her pink hair should have been a symbol of her own characteristics and freedom of expression, rather than a reason for being judged by the group of hate speech. After this tragedy, what we need is not only remembrance, but action—a collective effort to create a digital space that is safer, more compassionate, and truly inclusive. For her, and for the countless others like her who have been swallowed up by hate speech online.

References

Datta, A. (2025, February 22). Hate speech failures by Meta and X undermine German election [Illustration]. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/tech/news/hate-speech-failures-by-meta-and-x-undermine-german-election/

Döring, N., & Mohseni, M. R. (2019). Fail videos and related video comments on YouTube: a case of sexualization of women and gendered hate speech? Communication Research Reports, 36(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2019.1634533

Massanari, A. (2015). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807 (Original work published 2017)

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Michelle De Pacina (2023). Suicide of pink-haired Chinese woman sparks cyberbullying debate. Yahoo News. https://www.yahoo.com/news/suicide-pink-haired-chinese-woman-194335539.html

Flew, T. (2021). Disinformation and fake news. In Regulating platforms. Cambridge: Polity(pp. 115–118).

Fleck, A. (2024, October 21). 2 in 3 people often encounter hate speech online. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/33299/online-hate-speech-encounters/

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney. https://doi.org/10.25910/j09v-sq57

Young Post (2023). Pink hair unites women in fight against cyberbullying in China. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/yp/learn/learning-resources/english-exercises/article/3215295/study-buddy-challenger-pink-hair-unites-women-fight-against-cyberbullying-china

Be the first to comment