U.S., Chinese flags, TikTok logo are seen in this illustration(Picture: Reuters)

As the ban signed by US President Biden is going to take effect, TikTok, with 170 million American users, faces a shutdown. Many users have started looking for alternative platforms, with the most attention focused on another Chinese social media app – RedNote.

On January 13, RedNote topped the download charts in the US Apple store, with over 700,000 downloads. This digital migration is not only about users choosing a platform but also a contest for data domination between China and the US.

The user migration from TikTok to RedNote is blurring the cultural boundaries of digital social platforms. Some TikTok users are trying to find a new sense of community on RedNote, and many RedNote users welcome this as an opportunity for cultural exchange. They even encourage bilingual posts to build bridges for cultural communication. However, as discussions about culture and aesthetic expression intensify, conflicts are inevitable.

While the overall atmosphere in RedNote is friendly, we can still observe that cultural norms and a form of “soft hate speech” are subtly constructing digital cultural boundaries in a mild and reasonable way, viewing expressions that do not conform to mainstream cultural standards as “other”. The article discusses how the influx of “TikTok refugees” to RedNote enables new forms of hate speech through social regulation in the platform and the challenges for cross-cultural platform governance in digital public spaces.

Background and the Phenomenon of Digital Migration

1.1 The TikTok Ban Crisis and Its Geopolitical Context

TikTok, a global short-video platform under ByteDance, has been at the centre of geopolitical tensions and data security controversies since 2020 due to its platform background (Zeng & Kaye, 2022).

TikTok and RedNote apps are seen in this illustration (Picture: Voanews)

TikTok’s opaque algorithms have sparked concerns in the United States about national security and data sovereignty. The U.S. House of Representatives passed the TikTok divestiture bill on March 13, 2024, requiring ByteDance to sell its U.S. TikTok business within six months or face a ban on U.S. websites. On January 18, 2025, TikTok suspended its services in the United States, and the day after the suspension, the U.S. delayed the enforcement of the ban. The “ban crisis” TikTok faces is not only a digital cold war over national security but also a conflict over national data dominance.

As the second-largest country with the most TikTok users, the U.S. has a young creator base (aged 18-24) accounting for half of the total (Duarte, 2025). 700,000 users have opted for a ‘digital migration‘ to the Chinese social media app RedNote, marking a significant escalation in the ongoing digital cold war between China and the United States. For these users, however, this shift is more than just a simple platform swap, it represents a form of “cultural refuge.”

TikTok users are seeking a digital space that allows them to maintain their unique expression styles and cultural identities. As Cunningham and Craig (2019) have pointed out, when the original platform fails to meet creators’ needs and expectations, users actively seek alternative solutions.

1.2 RedNote platform

Rednote, as a Chinese social platform, fundamentally differs from global counterparts like Reddit and X in cultural governance. For instance, Facebook establishes a “value hierarchy” aligned with community standards during content moderation, sometimes prioritizing certain types of speech over others (Neves et al., 2022); Reddit, on the other hand, relies on user submissions and content generated by users, with extensive volunteer-driven efforts to formulate and enforce rules for individual subreddits (Massanari, 2015). Rednote’s platform governance constructs an aesthetic-driven, depoliticized environment through keyword blocking and algorithmic recommendations. The platform is also bound by Chinese data laws, with privacy policies lacking multilingual readability and limited transparency in datafication. Although seemingly inclusive, it inherently imposes implicit requirements on language, aesthetics, and expression.

In other words, Rednote may not be the alternative platform that some TikTok refugees envision, but rather the beginning of a new cultural adaptation dilemma.

Invisible Digital Cultural Boundaries

The cultural governance differences among platforms are not only reflected in content moderation but also in the collective regulation of language choices by user communities. Language regulation has become a norm for cultural expression and the power practises within platforms, forming invisible digital boundaries. As Foucault (1977) argued, discourse and language are not only tools for the production of knowledge but also means to maintain power structures. Language regulation is the primary challenge faced by TikTok users after migration.

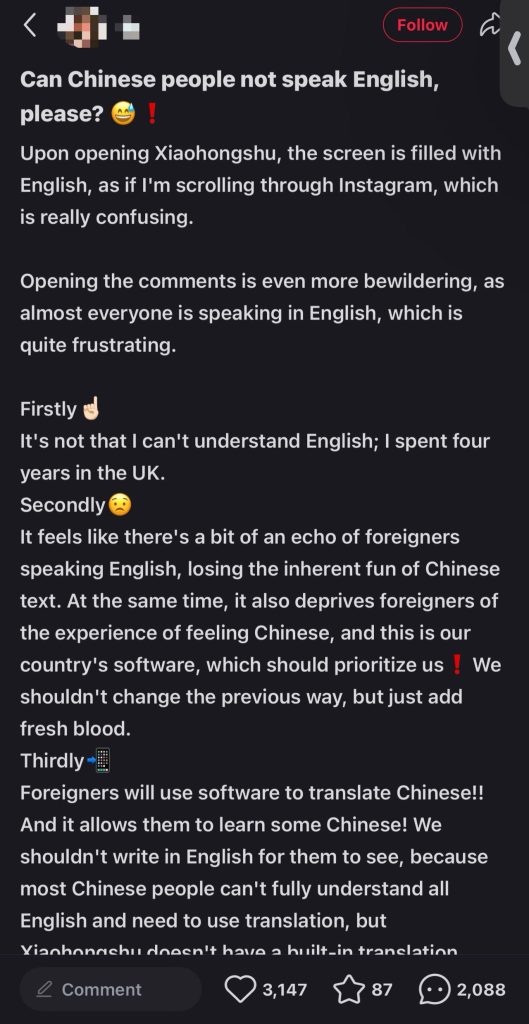

Figure1: Screenshot of the post about advocating for speaking Chinese from RedNote (photoed by Lu, 2025)

Since RedNote maintains only one version of the application, rather than splitting it into overseas and domestic versions, the default language environment is standard Chinese. Within just three days, a large number of TikTok users posted in English on RedNote. Numerous posts and comments advocating for “speak Chinese” were initiated (see Figure 1). These statements were not aggressive but reflected an underlying assumption of “language normativity,” gradually building a platform consensus on “digital language hegemony.”

Language hegemony refers to the dominant position of one language over others in a specific social and cultural context. This dominance is not only reflected in the number of users, and the power and prestige it carries, but also leads to the marginalization of other languages and their speakers (Khan & Sajid, 2024).

Language regulation reinforces the boundaries of the mainstream culture on the platform and marginalizes users of other languages, potentially leading to structural exclusion. Language plays a central role in shaping an individual’s social identity and sense of belonging (Khan & Sajid, 2024). Therefore, on the platform dominated by Chinese, users of other languages may suffer discrimination and marginalization due to language use, thereby losing their sense of belonging and interaction.

On January 19, 2025, just three days later, Rednote launched an automatic translation feature that allows users to directly translate English content within the Chinese interface. The emergence of this platform feature not only demonstrates the technical response to multilingual needs but also implies a market strategy to expand its overseas user base.

Globally, social media platforms face significant challenges in managing cross-cultural communication and multilingual content. Taking ShareChat, an Indian social media platform that supports multiple local languages, as an example, it still encounters issues with inadequate automatic detection and difficulties in manual review when dealing with a large amount of non-mainstream expressions and sensitive topics. ShareChat is tackling these challenges by developing multilingual moderation tools, such as AbuseXLMR, to ensure effective filtering of harmful content while accommodating diverse cultural expressions (Gupta et al., 2022).

Cultural Expectation = Cultural Exclusion?

The collective preference for “aesthetics” among RedNote users, shaped by the platform’s algorithmic structure and governance, has constructed a mild cultural exclusion mechanism.

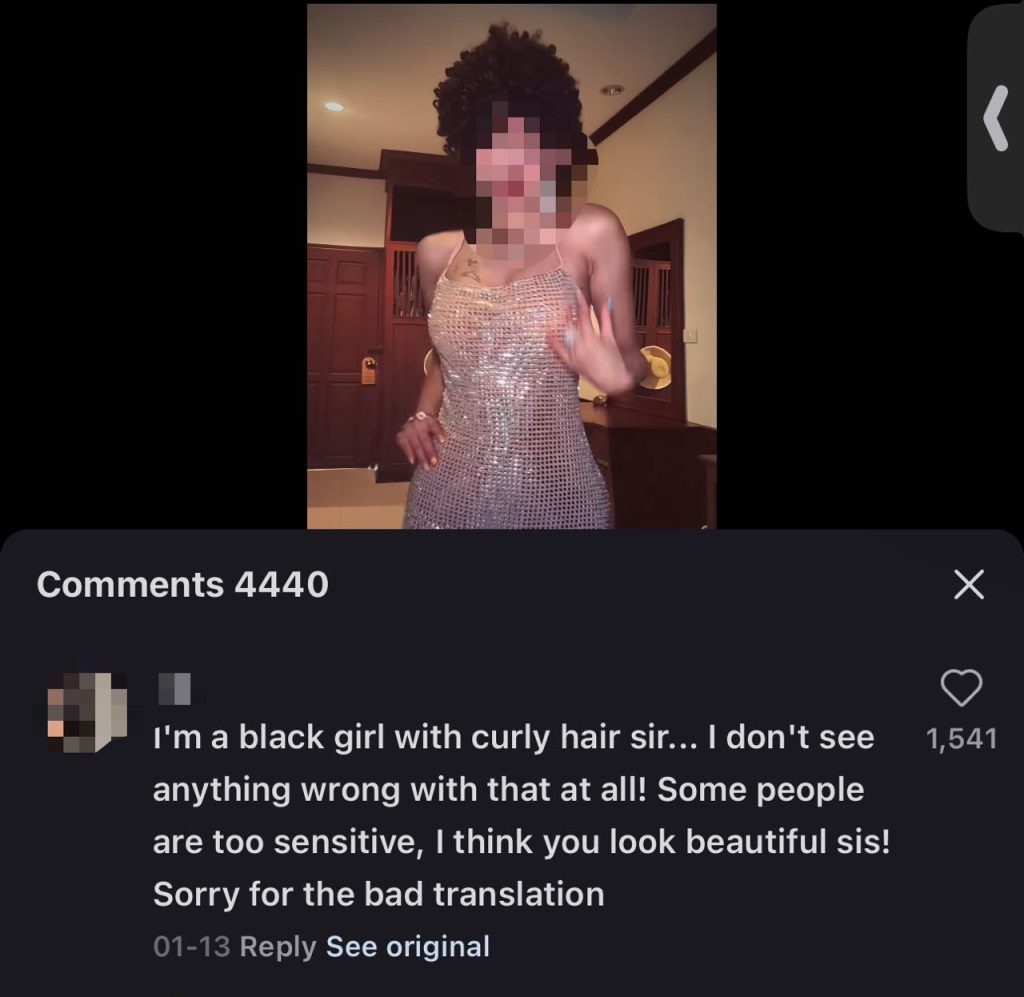

Figure2: Screenshot of the video about blogger dancing wearing big curly hairstyles and comments from RedNote (photoed by Lu, 2025)

On January 16, 2025, a Chinese blogger uploaded a video of herself dancing in a sequined dress and wearing big curly hairstyles in RedNote (see Figure 2). The comments section soon sparked a debate about “racial insensitivity” versus “freedom of expression.” Some users pointed out that the hairstyle might be associated with cultural appropriation from African American culture, while most others rebutted by saying, “You’re too sensitive; she looks beautiful.” The response, though not directly insulting, indirectly denies the discussion space regarding racial cultural expression, historical oppression, and discourse power. Another phenomenon is overseas users uploading selfies and asking “Am I pretty in China?” Some said it’s beautiful, while others give aesthetic advice like “remove your nose ring,” or “Chinese people don’t like tattoos.”

These comments subtly convey the cultural regulation that “standards of beauty should conform to the platform’s mainstream.” The RedNote seems to be a depoliticized entertainment platform, these daily interactions implicitly discriminate through exclusion and irony shaped by the platform’s mainstream aesthetics, language, and style of expression. “Platformed racism” uses algorithmic structures, community preferences, and normative speech to make certain cultures the default narrative.

Under platform algorithms, the default narrative requires cultural differences to prove their legitimacy (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

Subtle unequal treatment and sanitized racist remarks are commonplace and socially accepted (Matsuda, 2018).

Cultural exclusion, though not hate speech itself, provides the possibility for the legitimization of hate speech.

Utilizing humorous Memes as a form of hate speech

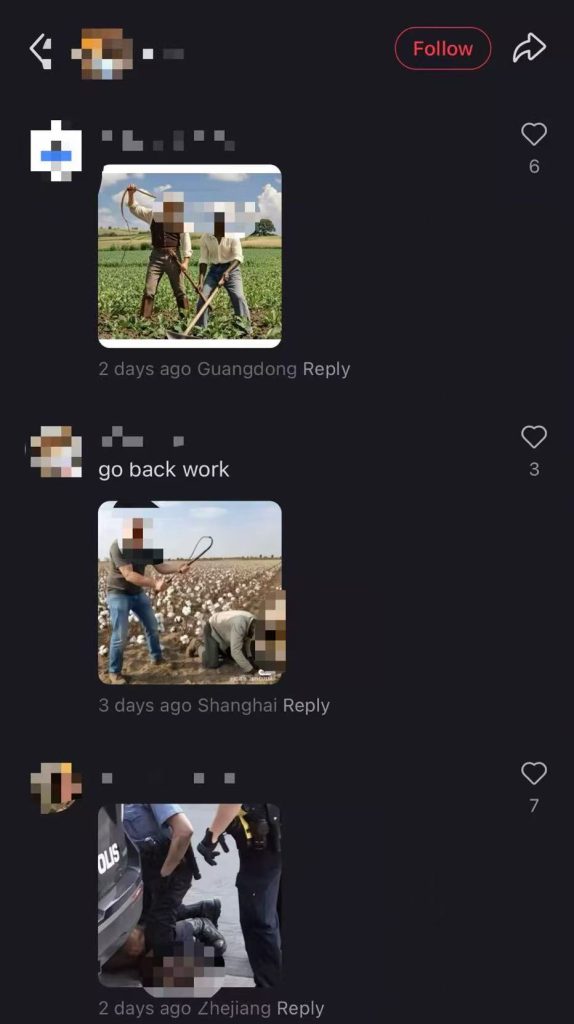

Figure3: Screenshot of the comments about discriminatory memes from RedNote (photoed by Lu, 2025)

On RedNote, many expressions are spread through visual elements such as emojis, memes, and screenshots. In numerous posts featuring selfies by Black users that the author reviewed, the comment sections almost invariably included discriminatory internet memes, such as “Black people picking cotton being whipped by whites.” These memes, with their ambiguous semantics, evade content moderation and continue to marginalize the Black people in the digital space.

Hate speech is not limited to words that offend or hurt emotions but refers to statements that can cause immediate and long-term harm, reinforce and perpetuate existing systemic discrimination, and target marginalized groups (Sinpeng, 2021).

This phenomenon is not unique to China. Australian Football League (AFL) Indigenous star Adam Goodes faced similar subtle hate speech. After performing an Aboriginal “war dance” during a 2015 match, he reignited debates about race and racism in Australia. On Twitter and Facebook, users shared memes comparing him to apes, tagging them with “humour” to bypass moderation. The technical architecture and algorithms of the Facebook platform, driven by economic interests, recommend more content attacking Goodes to users (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

These cases reveal how memes evade platform regulation and content moderation under the mask of “humour,” exposing barriers in platform governance. When hate speech is entertained and visualized, it both obscures the accountability of attackers and weakens the platform’s response mechanisms. As Matamoros-Fernández (2017) pointed out, the design of platform affordances, users’ behaviour in disguising hate speech, and algorithmic recommendation biases collectively contribute to platform-mediated racial discrimination.

How RedNote and its users move towards the future

In the process of globalization, RedNote’s market positioning is changing. In the past, it was a lifestyle platform for China’s middle class, but now it is moving towards a cross-cultural international platform. While this change brings opportunities, it also raises new challenges: how do users and platforms coexist? Can cultural differences be truly tolerated?

“TikTok refugees” are not just ordinary platform migrants, but also groups that are gradually marginalized in the context of RedNote’s digital culture. Their language, expression, and aesthetic orientation are different from that of mainstream communities, resulting in the regulation and discrimination of the platform’s mainstream culture during interaction.

Nowadays, for the cross-cultural platform RedNote, it is necessary to not only delete extreme content but also to establish a mechanism that can identify soft discrimination. For example, in order to deal with harmful speech in multilingual environments, ShareChat in India has developed a multilingual hate recognition system AbuseXLMR, which improves the accuracy of content review through context recognition technology; YouTube has been criticized for demonetizing LGBTQ+ content by default, and has improved its content rating algorithm to enhance the platform’s support for marginal groups’ expressions.

Through these experiences, RedNote can technically build a more refined content review model to reduce cultural exclusion caused by algorithmic bias. Secondly, RedNote needs to establish and update site guidelines or rules, ensuring that users comply with laws and regulations. In addition, establish a user reporting and feedback system to ensure that platform governance can be continuously updated with changes in user behaviour and international norms. Managing such a cross-cultural social platform is a long-term challenge, and we must continue to make efforts in three aspects: laws and regulations, technological innovation and user participation. In this way, structural exclusion can be eliminated in the global digital space and truly build an equal and inclusive public platform for multicultural exchanges.

References

Cunningham, S., & Craig, D. (2019). Creator governance in social media entertainment. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), 2056305119883428.

Duarte, F. (2025, March 25). TikTok User Age, Gender, & Demographics (2025). Explodingtopics. https://explodingtopics.com/blog/tiktok-demographics

Foucault, M., & Deleuze, G. (1977). Intellectuals and power. Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews, 205, 209.

Gupta, V., Roychowdhury, S., Das, M., Banerjee, S., Saha, P., Mathew, B., & Mukherjee, A. (2022). Multilingual abusive comment detection at scale for indic languages. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 26176-26191.

Hu, K. (2025). U.S., Chinese flags, TikTok logo and gavel are seen in this illustration taken January 8, 2025. [Photo].Thomson Reuters.

Khan, S. A., & Sajid, M. A. (2024). Language as a Tool of Power: Examining the Dynamics of Linguistic Hegemony and Resistance. Dialogue Social Science Review (DSSR), 2(4), 233-248.

Lu, Y. (2025). Screenshot of the video about blogger dancing wearing big curly hairstyles and comments from RedNote, 2025. [Photo].

Lu, Y. (2025). Screenshot of the post about advocating for speaking Chinese from RedNote, 2025. [Photo].

Lu, Y. (2025). Screenshot of the comments about discriminatory memes from RedNote, 2025. [Photo].

Massanari, A. (2015). # gamergate and the Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures.” new media & society.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930-946.

Matsuda, M. J. (2018). Public response to racist speech: Considering the victim’s story. In Words that wound (pp. 17-51). Routledge.

Neves, J., Chia, A., Paasonen, S., & Sundaram, R. (2022). Technopharmacology (p. 144). meson press.

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia pacific. Facebook Content Policy Research on Social Media Award: Regulating Hate Speech in the Asia Pacific.

Yang, W. (2025). TikTok and Xiaohongshu, or RedNote, apps are seen in this illustration. [Photo]. Voanews

Zeng, J., & Kaye, D. B. V. (2022). From content moderation to visibility moderation: A case study of platform governance on TikTok. Policy & Internet, 14(1), 79-95.

Zobel, G. (2019). Review of” Algorithms of oppression: how search engines reinforce racism,” by Noble, SU (2018). New York, New York: NYU Press. Communication Design Quarterly Review, 7(3), 30-31.

Be the first to comment