You can buy your privacy, and Meta is putting a price on it to users across much of Europe.

Imagine walking into a supermarket and seeing shelves full of “free” goods, but there’s a condition: you have to let the store record your every move. If you don’t want to be spied on, you have to pay €9.99 monthly. This isn’t a dystopian novel — it’s the reality Meta introduced in 2023.

Under its new “pay or consent” model, Meta offers European users two choices: pay a monthly fee for ad-free access to Facebook or Instagram, or continue to use it for free—at the cost of letting Meta track and collect your location, clicks, likes, and swipes, etc., to show you targeted ads.

Sounds fair, right? Not quite.

This model is not just a business strategy, it reveals the dangerous rules of the game in the digital age: your privacy is becoming a luxury that is traded. And this also raises the core question in today’s digital governance: Can your privacy be commoditized? Is privacy a privilege or a human right?

What is Happening?

In November 2023, Meta introduced a new subscription option for people who use Facebook or Instagram and live in the EU, EEA, and Switzerland to comply with EU data privacy rules. Users pay €9.99 monthly on the web or €12.99 on iOS or Android to get an ad-free version of Facebook or Instagram (Meta, 2024). These versions do not use personal data for advertising purposes. The data of users who do not pay will be used to customize personalized ads that appear in their social media feeds.

However, it has still sparked criticism from privacy advocates and concerns from European data regulators. In April 2024, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) issued an opinion stating that platforms offering paid, ad-free alternatives must consider providing additional options that do not compromise user rights (McMahon, 2024).

In November 2024, Meta changed its subscription prices in response to the concerns of EU regulators. It reduces the price of a monthly subscription from 9.99 € to 5.99 €/month or from 12.99 € to 7.99 €/month.

Meta said,

“A year ago, we launched Subscription for no ads in the EU to comply with changing regulatory requirements, specifically the GDPR and the DMA. Offering a choice between a paid subscription and free access to a service funded by personalized ads is a well-established business model and a valid legal consent choice under EU law, as supported by a judgment given by the Court of Justice of the European Union.“

Meta maintains the model to comply with EU law, offering users a real choice. However, does this choice constitute a meaningful choice? Meta may define privacy differently than the public.

Is Privacy a Human Right?

Under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), privacy is a fundamental right. It means the data cannot be collected, processed, or sold without the user’s informed and free consent. Flew (2021) emphasizes that the right to privacy is seen as an inherent human right despite restrictions in practice.

Nonetheless, here things get tricky. If Meta offers a “pay or accept tracking” model, is this consent really freely given? Or is it just a carefully designed trap for freedom of choice?

- · Pricing Pressure: Many users cannot afford to pay a monthly fee, effectively coercing them into surrendering their data. It creates a “privacy tax” that forces people to trade personal information for access.

- · Binary choice: EU antitrust regulators accused Meta of violating the Digital Markets Act, saying that its paid ad-free service constitutes a binary choice for users. It divides users into those who can pay for privacy and those who must hand over their personal information. This exacerbates existing inequalities and fundamentally attempts to change our view of digital rights.

Additionally, Meta still provides personalized advertising to most consumers by collecting data. Platform companies view privacy and data as capital accumulation, and their income comes from selling ads (Suzor, 2019). The large-scale extraction and monetization of personal data is the core business model of big tech companies and countless others. To this extent, the legal relationship between providers and users is the legal relationship between companies and consumers, not the sovereigns and citizens. Legally speaking, it makes no sense to talk about “rights” in these consumer transactions (Suzor, 2019).

Flew (2021) further mentioned that the right to privacy is not an absolute human right but a human right based on a specific social and legal context. In the context of digital capitalism, privacy seems to be challenging to be a fundamental right, but it has become a privilege controlled by technology companies.

Is Privacy a privilege?

The discussion of whether privacy has become a privilege is a commonplace topic. After all, we have accepted too much information collection by companies and governments by default and “lost” privacy. The Guardian pointed out that in 2010, Mark Zuckerberg said that privacy is no longer a social norm, which is probably the reason for changing the default settings of Facebook’s 350 million users to reduce privacy (Montgomery, 2023).

In practice, achieving privacy often requires making choices and creating privileges that make this freedom possible (Marwick & Body, 2018). And Meta’s way of paying for privacy seems to be to change privacy from an ordinary right to a privilege that needs to be purchased. The ability to protect one’s privacy increasingly depends on one’s ability to pay.

Meta believes that paying to avoid advertising can protect users’ privacy, but this is based on Meta user data collection. It recognizes the commoditization of privacy and that privacy is sellable.

As privacy advocacy group and nonprofit NOYB (2023) criticized, this model rationalizes the commodification of personal data and basic right. They argue that Meta’s subscription merely adds a price tag to consent—failing to make it any freer than previous consent models.

It is undeniable that privacy is becoming a luxury.

Users need to give up their data for free and pay for privacy protection, which will exacerbate digital inequality.

The Privacy Paradox

In fact, many people in the digital age have long stopped believing they can have absolute privacy.

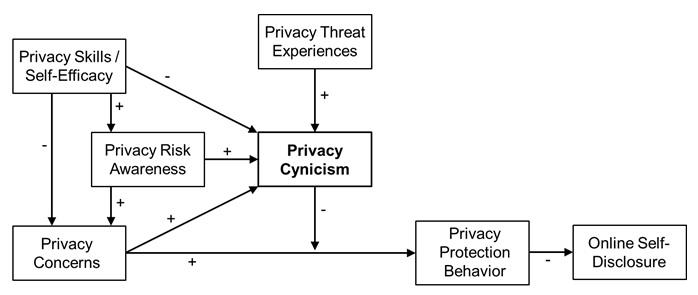

It brings us to the concept of the Privacy Paradox, that is, users are worried about privacy security on the one hand, but are keen to share personal privacy information on the other hand (Barnes, 2006). The privacy paradox has become the norm, and the obvious inconsistency between privacy concerns and actual disclosure has also improved many thoughts.

Hoffmann et al. (2016) introduced that privacy cynicism refers to the user’s uncertainty, distrust, and powerlessness in processing personal data through digital platforms, making privacy protection subjectively futile. It may explain why 82% of American adults in the survey said they were unwilling to pay for an ad-free version of Facebook or Instagram(Statista, 2025).

NOYB (2023) also indicated that only 3% to 10% of people want personalized ads, but 99.9% of people choose to agree.

However, the Meta case has pushed the privacy paradox into a new area. Here, it is not just about carelessness, fatigue, and inability to do anything. Users are forced to choose between money and privacy. It is not a meaningful choice for many, especially young or low-income users. It is more like a privacy paywall. As Max Schrems, Chairman of NOYB, put it:

“Fundamental rights are usually available to everyone. How many people would still exercise their right to vote if they had to pay € 250 to do so? There were times when fundamental rights were reserved for the rich. It seems Meta wants to take us back for more than a hundred years.”

Users may not be able to choose to protect privacy on their own due to economic pressure. Here, choice is an illusion, cynicism is forced, and whether privacy can be protected depends on our (economic) ability.

But in essence, Meta’s business model also presents a paradox about privacy. Meta’s business model has not changed at all. Perhaps paid subscriptions are just a disguised wallpaper for surveillance capitalism. Whether users are willing to pay has no effect on Meta: the ultimate goal is not to get money from 1% of users but to prove that it is reasonable to use the data of the other 99% of users. What users find difficult or tiring to do is to have the right not to be disturbed truly. As Marwick and Boyd (2018) said, network technology has complicated information dissemination dynamics, so most people find themselves constantly negotiating between disclosure, concealment, and connection.

Where is the Regulation?

In the EU, data protection is taken seriously. Under the GDPR, companies need to give informed consent to process your data freely. Moreover, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) is designed to control the power of large technology companies. Meta’s new model claims to comply with GDPR and DMA. After Meta’s paid privacy model was launched, several European institutions also raised new protests.

European Consumer Organization (BEUC) filed a complaint, calling the price “very high” and saying that Meta is using “unfair, deceptive and aggressive practices” while providing consumers with “misleading and incomplete information” (Montgomery, 2023).

BEUC Director General Agustin Reyna said,

“We believe that the tech giant has failed to address the fundamental problem that Facebook and Instagram users do not have a fair choice, and is weakly arguing that it complies with EU law while still pushing users into its behavioral advertising system.”

The European Commission, the EU’s executive body, said the model dose not align with the DMA.

Meanwhile, 28 privacy protection organizations jointly signed an open letter to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), urging it to take action against this model.

Nevertheless, such regulation has yet to get a new, clear answer.

Part of the problem is that digital governance has not kept pace with platform innovation. Laws like GDPR were groundbreaking when they were introduced in 2018, but platforms like Meta have found creative ways to work around them, often exploiting vague language or regulatory gray areas.

Furthermore, while the CJEU has questioned Meta’s “legitimate interest” claim, lengthy proceedings have allowed platforms to continue harvesting data. The lag in regulation essentially acquiesces to the logic of “breaking the law means making a profit.” And even if GDPR fines are already relatively strict, they may only be the price of a cup of coffee for Meta’s hundreds of billions of dollars in profits. Meta paid a huge fine (such as 1.2 billion euros in 2023) but refused to make corrections, passing the fine cost to advertisers, and ultimately users “compensated” by giving up their privacy. At this level, regulation is just a good-looking empty frame, and it has become a tool for platforms to consolidate their monopoly and whitewash their legitimacy.

The question regulators face now is: How can they protect users when powerful platforms redefine consent according to their own terms?

What Should Be Done?

Meta’s model is not unique. Across the digital scape, companies are monetizing privacy. YouTube, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok (McMahon, 2023) are all experimenting with ad-free subscription models. All of this points to a broader trend: companies are realizing that privacy can be sold as a feature, which is changing the nature of digital rights.

They could seriously undermine global efforts to strengthen digital rights, and to minimize the commoditization of privacy, we can consider strengthening digital governance at several levels:

- 1. Regulatory clarity: The regulator must not only react to the latest moves of big tech companies but also anticipate them and set clear rules on what constitutes valid consent and privacy protection.

- 2. Public awareness: Most users are trapped in the privacy paradox, and we need more education and publicity to improve our digital media literacy and privacy security awareness.

- 3. User-centric governance: Legislation recognizes the user’s property rights over data and implements the right to privacy as a basic human right.

- 4. Support for alternatives: enhance the role of third-party institutions, and support open-source tools and platform companies that prioritize privacy.

Conclusion: Privacy Should Not Become Luxury

Meta’s ad-free subscription may seem like a small change, but it represents a deeper shift in how privacy is treated in our digital lives. It uses the rhetoric of “freedom of choice” to cover up rights deprivation and the narrative of “compliant innovation” to dispel regulatory resistance.

When privacy becomes something you can buy, it is no longer a right but a privilege.

Perhaps the commodification of privacy has become a global trend, and we can hardly resist the exploitation of privacy, whether out of privacy cynicism or limited ability. But at least we should not let privacy go from a commodity to a luxury. Even if we cannot avoid privacy being traded, at least we must resist its transformation into an exclusive privilege. How we respond to this moment will also affect the future of digital governance.

As users, we must demand more transparency, better choices, and laws protecting our data. As a society, we must ensure that digital rights are not something you must buy but a fundamental right by default.

We cannot resist the wave but will always remember the lighthouse. Because the question is not just whether Meta can do it, but whether we can only play by their rules.

References:

- Barnes, S. B. (2006). A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v11i9.1394

- Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity.

- GDPR representation [Image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.arin6902.net.au/wp-admin/post.php?post=16793&action=edit

- Hoffmann, C. P., Lutz, C., & Ranzini, G. (2016). Privacy cynicism: A new approach to the privacy paradox. Cyberpsychology, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2016-4-7

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International journal of communication [Online], 1157+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A561120196/AONE?u=usyd&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=3df64beb

- McMahon, L. (2023). TikTok testing out advert-free monthly subscription [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-66941340

- McMahon, L. (2023). EU says Instagram’s paid ad-free option breaches rules [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/clky017yl1jo#

- Meta (2024). Facebook and Instagram to Offer Subscription for No Ads in Europe [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://about.fb.com/news/2024/11/facebook-and-instagram-to-offer-subscription-for-no-ads-in-europe/#:~:text=Originally%20published%20on%20October%2030,in%20a%20user%27s%20Account%20Center.

- Meta logo, EU flag and Judge gavel are seen in this illustration taken [Image]. (2024). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/technology/metas-revised-paid-ad-free-service-may-breach-eu-privacy-laws-consumer-group-2025-01-23/#:~:text=BEUC%20alleges%20that%20Meta%27s%20misleading,a%20binary%20choice%20for%20users.&text=An%20agenda%2Dsetting%20and%20market,never%20fail%20to%20charm%20readers.

- Montgomery, B. (2023). Is Meta’s ad-free service just another way to make people pay for privacy? [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/dec/05/is-metas-ad-free-service-just-another-way-to-make-people-pay-for-privacy

- NOYB (2023). noyb files GDPR complaint against Meta over “Pay or Okay” [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://noyb.eu/en/noyb-files-gdpr-complaint-against-meta-over-pay-or-okay?utm_source=simpleanalytics.com

- People have become more comfortable sharing private information online, says Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg [Image]. (2010). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2010/jan/11/facebook-privacy

- Statista (2025). Share of adults in the United States on monthly amount they would be willing to pay for an advert-free version of Facebook and/or Instagram as of November 2023, by generation [Online]. Retrieved from April 13, 2025, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1428098/us-adults-ad-free-facebook-instagram/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern our Digital Lives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Be the first to comment