Imagine this, you’ve just shared a photo of a family gathering on Facebook, set to “Friends only”. A few days later, your colleague mentions the photo over lunch. Confused, you begin to wonder: What is the use of my carefully adjusted privacy settings?

If this scene sounds familiar, you’re not alone. In today’s digital age, most of us share every aspect of our lives on social media, from breakfast photos to professional achievements, from family gatherings to personal opinions. Social media platforms claim that through their privacy settings, we can control who can see this content. But the question is: Do these privacy settings really work as well as the platform claims? Are users really benefiting from this?

Complexity of social media privacy

To understand the complexity of social media privacy, we first need to recognize a basic fact: Social media companies are commercial entities whose primary goal is to make a profit. User data is one of their most valuable assets. As digital rights expert Nicolas Suzor points out in his book Lawless: the secret rules that govern our digital lives, the platform’s business model relies on collecting as much user data as possible and using that data to provide precise AD targeting services. (Suzor, 2019, p. 15)

This immediately raises a fundamental contradiction: How do platforms balance user privacy needs with the commercial imperative of data collection? The answer is often embodied in complex and constantly changing privacy policies and settings that often leave the average user confused and powerless.

Helen Nissenbaum’s theory of “contextual integrity” provides a useful framework for understanding this problem. She believes that privacy is not just about controlling the flow of information, but ensuring that information flows in the appropriate context. When information flows in contexts that do not conform to social norms, our privacy is violated (Nissenbaum, 2018, p. 834). In a social media environment, users may expect photos to be shared only within their circle of friends, but the platform may use this data for advertising purposes, thus undermining contextual integrity.

The reality of privacy settings

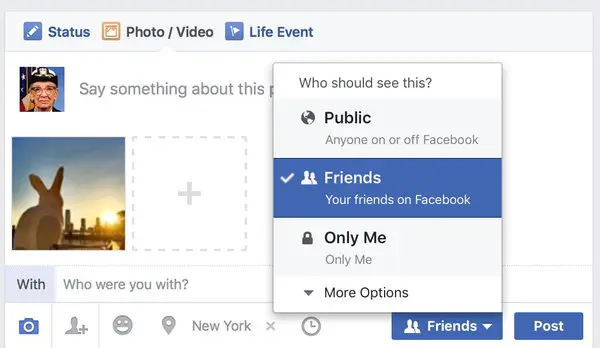

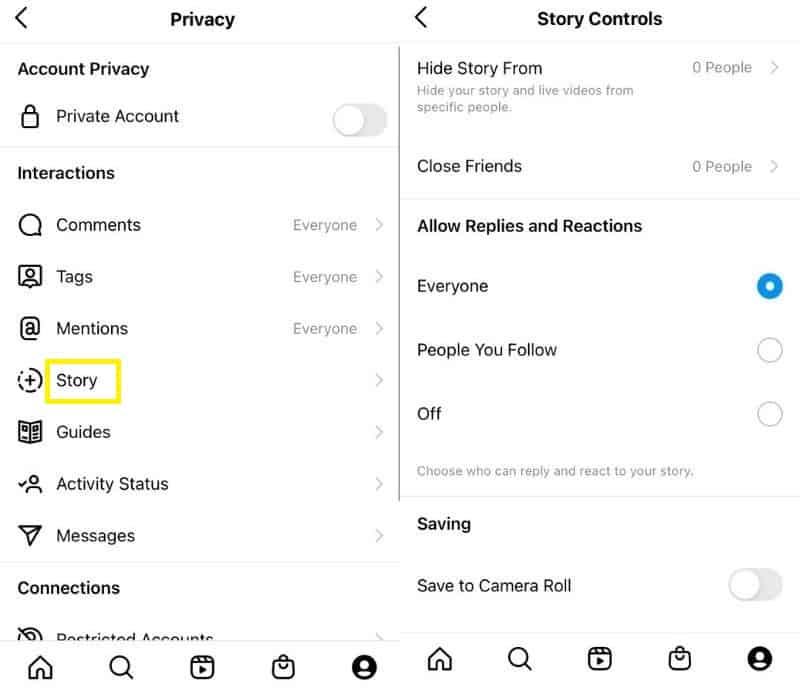

Most major social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok, offer a range of privacy settings. These settings often allow users to decide who can see their posts, who can send friend requests, who can tag them, and so on. At first glance, this seems to give the user plenty of control.

The reality, however, is often more complex. For example, Facebook has had its privacy settings interface modified and “simplified” over the years, but many users are still confused. According to Digital Rights in Australia, although social media platforms provide privacy settings, these settings often default to the benefit of the platform rather than the user and are constantly changing, making it difficult for users to keep up (Goggin et al., 2017).

Moreover, even if users are well-versed in these settings, they have no control over how the platform uses their data for internal analytics, AD targeting, or sharing with third parties. As Terry Flew points out in Regulating Platforms, privacy settings are primarily concerned with information sharing between users, not how the platform uses that data (Flew, 2021).

Case study: Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal

There is no better example of the limits of social media privacy settings than Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal. In 2018, Revelations revealed that data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica obtained the personal data of up to 87 million Facebook users and used the data to create psychological profiles to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Shockingly, the data was collected using a seemingly innocuous personality quiz app called “This Is Your Digital Life”, which only around 270,000 users have actively installed. However, due to Facebook’s API settings at the time, the app was able to access the data of those users’ friends, greatly expanding the scope of data collection.

While users may have carefully set their privacy options, they have no control over how the platform’s API policies allow third-party apps to access their data. The incident revealed a fundamental flaw in social media privacy settings: they primarily focus on visibility between users, rather than how the platforms and their partners use user data.

As Marwick and Boyd point out, privacy is not simply a matter of individual choice, but is shaped by technological infrastructure, business models, regulatory frameworks, and social norms (Marwick & Boyd, 2018, p. 1159).

Privacy challenges for marginalized groups

When we discuss social media privacy, it’s important to recognize that not all users face the same risks and consequences. For marginalized groups – such as the LGBTQ+ community, political dissidents, survivors of domestic violence, and others – threats to privacy can have serious real-world consequences.

In their research, Marvik and Boyd looked specifically at the concept of “marginal privacy,” or how those with less power understand and respond to privacy challenges. They found that for these groups, privacy is not just about protecting personal information, but about survival and dignity. When platforms’ privacy Settings fail to adequately protect marginalized groups, the consequences can be devastating, including harassment, discrimination, and even physical harm (Marwick & Boyd, 2018, p. 1163).

For example, a transgender person may adopt a new identity and name on social media while wanting to isolate that information from certain family members who do not accept their gender identity. However, the social media platform’s algorithms may automatically recommend these family members to follow or add the user, inadvertently “outing” them. In this case, even if users carefully set their privacy options, the platform’s recommendation algorithm may still undermine their privacy expectations.

Design flaws in privacy settings

Numerous studies have shown that the privacy settings of social media platforms have fundamental flaws in their design that limit their effectiveness.

First, most platforms adopt a “public by default” model, meaning that unless users actively change their settings, their content will be visible to a wide audience. This “opt-out” rather than “opt-in” approach benefits the platform because it maximizes content visibility and user engagement, but puts the onus of privacy squarely on the user.

Second, privacy settings are often overly complex and unintuitive. Nissenbaum (2018) states that “the privacy controls provided by platforms are often technical and inconsistent with users’ actual understanding and expectations of privacy” (p. 839). For example, users may understand the concept of “friends” but not necessarily how categories such as “friends of friends” or “connected apps” affect their privacy.

Third, privacy settings change frequently, making it difficult for users to keep up. Facebook is notorious for making frequent changes to its privacy policies and settings, requiring users to relearn and adjust their settings with each change. This “change fatigue” can cause users to give up trying to manage their privacy altogether.

Finally, as Kari Karppinen emphasizes in Human rights and the digital. In Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights.:” Digital rights, including the right to privacy, should be viewed as fundamental human rights, not as an optional feature of consumer services” (Karppinen, 2017, p.98). However, social media platforms often treat privacy settings as a service feature rather than a fundamental right, which fundamentally limits their effectiveness.

The data economy and the commodification of privacy

To fully understand the limitations of social media privacy settings, we need to consider the broader economic context in which they exist: the data economy. In this economy, user data is treated as a valuable commodity, used to predict user behavior, target advertising, and develop new products.

As Terry Flew explains in Regulating Platforms,” The business model of social media platforms is essentially monetizing user attention and data” (Flew, 2021, p.75). In this model, platforms have a strong incentive to collect as much user data as possible and restrict its use as little as possible.

Privacy settings in this context become a balancing tool: they provide enough sense of control to appease users’ privacy concerns, but not so much as to materially compromise the platform’s data collection capabilities. This “superficial privacy” gives users the illusion of control, but in fact fails to address the fundamental issues of data collection and use.

Nissenbaum (2018) describes this phenomenon as a failure of the “notice-and-consent” model, in which platforms obtain formal consent from users through lengthy privacy policies and complex settings, but do not actually provide meaningful privacy protections. When users are faced with complex privacy policies, they often simply click ‘agree’ without reading the content. This ‘notice and consent’ has in practice become a ritual rather than a meaningful privacy protection mechanism. (p. 841)

Privacy implications of algorithms and automation

The algorithms and automated systems of social media platforms have profound implications for user privacy that often extend beyond the confines of traditional privacy settings.

As Kate Crawford highlights in The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence.:” AI and machine learning systems are capable of extracting surprisingly personal information from seemingly innocuous data” (Crawford, 2021, p.8). For example, Facebook’s algorithms can infer a user’s political views, sexual orientation, or health status by analyzing their likes, comments, and browsing behavior, even if the user never shared that information directly.

This “inferred privacy” problem challenges the effectiveness of traditional privacy settings. Users may have tight control over the information they actively share, but not over the information the platform extrapolates from their actions. As Mark Andrejevic states in ‘Automated Culture’, in Automated Media.: “Traditional privacy controls become increasingly irrelevant when automated systems are able to infer our preferences, behaviors, and attributes from our digital footprint” (Andrejevic, 2019, p.50)

Regulation and solutions

Faced with the limitations of social media privacy settings, many experts are calling for more regulation and new approaches to privacy protection.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation represents an important attempt in this direction. The GDPR requires platforms to implement the “privacy by design” principle, which means that privacy protection is considered at the beginning of product design, rather than added after the fact. It also introduced a “right to be forgotten”, allowing users to request the deletion of their personal data.

However, as Safiya Noble points out in A society, searching. In Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism.:” Regulation alone is not enough, we need to rethink the business models and underlying technologies of digital platforms” (Noble, 2018, p.28). Some experts advocate alternative business models, such as subscription or user owned collaborative platforms, to reduce reliance on monetizing user data.

Nissenbaum (2018) proposes “contextual integrity” as a new framework for privacy protection in design, emphasizing that information should flow according to norms in a particular social context. Privacy protection should not only be about controlling access to information, but about ensuring that information flows in the appropriate context (p.845).

Conclusion: Go beyond privacy settings

Back to our original question: Do the privacy settings of social media platforms really benefit users? The answer is complex.

On the one hand, existing privacy settings do provide a degree of control, allowing users to manage who in their social circle can see what. This control is valuable for navigating complex social relationships.

On the other hand, these settings have significant limitations. They focus on content visibility between users, rather than how the platform uses user data. They are often complex and unintuitive. Their default settings tend to benefit the platform rather than the user. They are not up to the privacy challenges posed by algorithmic inference and data analysis.

On top of that, current privacy settings put the onus squarely on the user, requiring individuals to protect their privacy in unequal power relationships. As Suzor puts it: “Treating privacy as a personal responsibility ignores the fundamental inequality of power between platforms and users” (Suzor,2019, p.18).

True privacy protection needs to go beyond personal settings and include strong regulatory frameworks, new business models, better privacy design principles, and a renewed understanding of digital rights as fundamental human rights. Only through this holistic approach can users truly benefit from social media without having to sacrifice their privacy and autonomy.

The next time you adjust Facebook’s privacy settings, remember this: You can control whether your friends see your photos, but the platform is still watching, analyzing, and potentially using your data in ways you didn’t expect. True privacy requires more than the click of a few settings buttons-it requires us to collectively rethink how digital platforms are designed, business models, and regulated.

References:

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Media. Routledge.

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In T. Flew, Regulating platforms (pp. 72–79). Polity.

Goggin, G. (2017). Digital Rights in Australia. The University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/17587

Karppinen, K. (2017). Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95–103). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835

MARWICK, A. E., & BOYD, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1157–1165.

Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Respecting Context to Protect Privacy: Why Meaning Matters. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(3), 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9674-9

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism . New York University Press.

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Be the first to comment