1. The Xiaomi SU7 Incident: A Tragedy of “Smart” Technology Out of Control

In the spring of 2025, a tragic accident involving Xiaomi’s SU7 autonomous vehicle resulted in the deaths of three young women.

Figure 1: Xiaomi SU7 car accident pictures

Although the cause of the crash remains under investigation, the incident has attracted intense public attention—particularly regarding whether the car’s “intelligent assisted driving system” was active at the time, and whether a technical malfunction or algorithmic misjudgment may have contributed to the crash.

It can be noticed that this tragedy is not an isolated case. Similar fatal incidents have occurred with other autonomous vehicle manufacturers, such as Tesla and NIO.

What shocked the public was not only the sudden loss of life, but also a deeper, more unsettling question: Can we truly trust artificial intelligence? When AI becomes the invisible driver behind the wheel, do we still have the right—or even the sufficient ability—to question or override its decisions?

Before we can meaningfully discuss the technical limitations or ethical responsibilities of AI systems, we must first confront a fundamental truth: algorithms are not neutral. They never have been.

2. Algorithms Are Not Neutral: From Tools to “Participants”

Tarleton Gillespie (2014) stated that algorithms are inevitably reflected the values of their designers, so it cannot be viewed as neutral or unbiased technological tools. Since the designers are shaped by social norms and power structures, so the algorithms are “the power of culture”.

As Dallas Smythe(1977)point out that consumer’s attention as commodities sold to advertisers and marketers over decades, in the digital era, this theory has been amplified: AI powered platforms, like Xiaomi, record consumer’s behavior, collect and analyze them to maximize their income. The data that supposedly lay within individuals or in the public commons were effectively appropriated and recoded as private capital or assets (Birch & Muniesa 2020, Pistor 2019, Sadowski 2020), The platforms defined the personal data that were produced through cookies and trackers as abundant and free for the taking.

figure 2: The Definition of Algorithms

Algorithms do construct reality. As Shoshana Zuboff (2019) contends in her theory of “surveillance capitalism,” AI operates within a predictive economy whose goal is not only to forecast the future, but to control it—from consumer behavior to political inclination.

Decisions made by autonomous vehicle is not just to brake or accelerate but also balancing the critical factors among “risk tolerance,” “efficiency optimization,” and “commercial liability”, which all affect real human lives, ultimately. The recent controversy surrounding Xiaomi’s SU7 highlights the urgency of critically examining whether AI systems truly serve the public interest—or primarily the profit motives of private corporations.

3. Who is Co-Driving with AI? — The Ideological Apparatus of Symbiosis

Microsoft’s CEO, Satya Nadella, has suggested that the ideal relationship between humans and AI should be a “co-pilot” model. He emphasizes we should treat AI as smart, behind-the-scenes teammate who helps you write, think, and get stuff done; however, we MUST stay in the driver’s seat. Whether it’s at work or life, never let AI taking over, but instead teaming up with it for a smoother ride. But this ideal story, too, needs to be critically examined.

Figure 3: Microsoft previews unified AI “Copilot” initiative

Back in 1971, philosopher Louis Althusser argued that ideology works not by force, but by getting us to willingly participate. This idea is surprisingly relevant today. The story of ” co-pilot ” might just be a new form of soft control. AI can manipulate people’s decisions through subtle heuristics and biases. Moreover, these subtle influence strategies can potentially impact on decisions, people feel that they are making autonomous choices, however, those choices may not align with their own interest.

As a result, people are increasingly predisposed to rely on Algorithmic when addressing difficult, thorny issues, especially in the field of autonomous driving. The drivers believe that they’re still in control when using AI—like it’s just a smart tool. However, they end up handing over those quick, instinctive judgments—like assessing real-time risk—to the system.

As Dubber et al. (2020) pointed out that the displacement of human judgment and the deterioration of conditions for its exercise are all too familiar. AI does not involve “thinking”, it potentially tames humans into perfectly compliant, machine-compatible decision units.

4. Platform Logic: Who Do Algorithms Serve?

The Xiaomi SU7 isn’t just a car; it’s a “mobile gateway” into the entire Xiaomi ecosystem. It collects user data, runs AI systems, and seamlessly connects with Xiaomi’s IoT products. This kind of control over hardware, software, content, and services is what we call vertical integration. By taking charge of key elements like the operating system, smart devices, and app stores, Xiaomi has successfully tapped into user data and traffic. This gives them a major role in shaping the rules of the game and puts them in a powerful position within their own ecosystem. So, today’s AI-driven platforms, from Xiaomi to Tesla, are no longer just passive vehicles, they are active agents shaping our behaviors.

As we discussed above, algorithms are not neutral. This brings us to a bigger question: when AI systems are built and deployed by private companies for profit maximizing purpose, can we still trust their decision-making public-minded? Who decides and how decides the definition of “safe”? Is the car’s braking and accelerator threshold based on optimizing user safety, or is it quietly balancing that against minimizing legal and financial risk of the platforms?

Today, Barbrook and Cameron’s famous critique of the “Californian Ideology” is more relevant than ever. Covered by the free-market slogans and tech utopianism, today’s AI industry highly promotes their innovations, but rarely talk about the consequences. And when machines make life-and-death decisions, that silence becomes dangerous.

Figure 4: Apple Park

Source: https://apple-store.ifuture.co.in/blog/apple-headquarters-apple-park/

5. The Triple Challenge of Algorithmic Governance: Institutional Silence

5.1 the challenges of Legal and Ethical: Can Algorithmic Decisions Be Contested?

Mounting controversies around algorithms of legal or ethical implications in recent years have caused public concerns. It may derive from corporate secrecy and complexity of algorithms. Frank Pasquale (2015) referred to this phenomenon as “black box society”.

On the one hand, algorithmic functions are often extremely complex and may involve millions of interdependent values or parameters. The rationale behind their decision-making processes can be difficult for humans to interpret, making it challenging for the public to fully understand or scrutinize these decisions. On the other hand, platforms protect their proprietary interests by share little information about their algorithms. The lack of transparency further exacerbates public distrust.

In the Xiaomi SU7 accident, the public had limited access to information about how the vehicle’s intelligent driver-assistance system functioned and made decisions.

When the incident occurred, the vehicle—operating under the Navigate on Autopilot (NOA) mode—failed to respond effectively within the short time window before the collision. Although the system detected the obstacle approximately two seconds prior to impact, control was handed over to the driver only one second later, placing considerable pressure on the driver to react almost instantaneously.

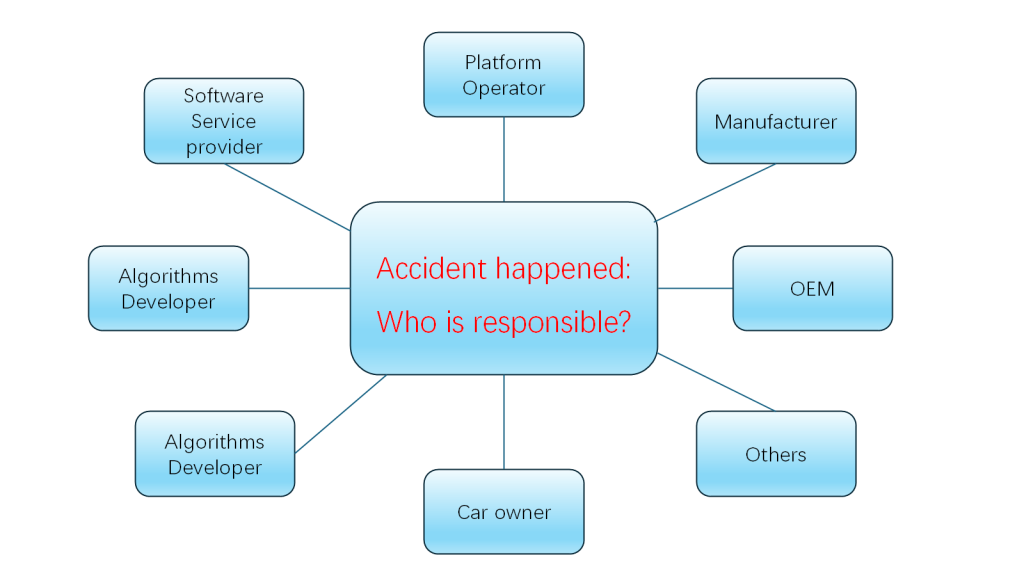

figure 5: Who is responsible?

After the accident, the company emphasized that the collision took place after the driver had taken over control, thereby shifting the narrative focus onto user error, rather than making reflection on the inherent limitations of the automated system. This aligns with the logic of “technological utopianism” and the notion of “tool innocence” described by Barbrook and Cameron (1996).

Furthermore, the system’s “black box” nature, as the root cause, conceals not only its operational logic but also the company’s ambiguous delineation of technological boundaries and its lack of accountability in public discourse.

5.2 Accountability in Question: Who is responsible for a machine’s decisions?

Zuboff (2019) pointed out, algorithms are not “naturally generated” but are purposefully designed by humans to achieve specific goals. Therefore, systems based on algorithmic design and the liability issues that may arise should not be fictitious as “no man’s land”, but should be clearly attributed to the developers, deployers and users of the algorithmic model.

The Xiaomi SU7 accident in 2024 not only raised technical questions but also challenged the existing institutional responsibility mechanism.

Although the legal responsibility of L2 assisted driving still mainly belongs to the driver according to current legal provisions, the design and operating characteristics of intelligent driving systems may in fact affect driving behavior.

For example:

- How long does it take for the system to identify obstacles and issue warnings?

- Is its computing power sufficient to cope with complex or extreme road conditions?

These questions all point to the potential liability of AI system designers and operators.

Therefore, establishing a clear and dynamic legal responsibility allocation mechanism to cope with the new responsibility structure of “distributed decision-making” of AI systems has become an urgent task for the legal system.

5.3 The Impact on Human Behavior: Are We Still Capable of Judgment?

Human being tends to lose their capacity for critical thinking due to their long-term dependence on AI decision-making systems. For instance, drivers highly rely on the “optimal route derive from navigation systems, algorithm regard as “reasonable” to replaces our own sense of judgment.

This phenomenon illustrates a trend that individuals are outsourcing their thinking to algorithmic systems. Wherein human is coded to computational logic. The algorithm is not merely a tool- it becomes an authority. So, people will not choose to question or override algorithmic.

This behavioral shift may have profound and long-term influence on the governance and education. If individuals are not encouraged to interrogate, contextualize, or object algorithmic authority, the foundation of autonomous thinking may erode. The challenge is thus not only technological, but also philosophical and pedagogical: how do we maintain human agency?

6. Why Humans Must Always Make Final Decision?

People often say, “AI is unstoppable,” but frankly, that shouldn’t be the case. The tragic Xiaomi SU7 accident reminds us that technological progress must never come at the cost of human life.

Satya Nadella repeatedly reminds us that AI should be a “co-pilot,” not a replacement for humans. He is right in spirit. But this is not just a technological issue; it raises deeper societal challenges that force us to rethink how we govern, how we educate, and how we define accountability. No matter how advanced AI becomes, we must ensure that humans always have the final say, especially when lives are at stake.

Because the fact is: Technology can assist, but it cannot determine what’s right.

AI can predict, optimize, and analyze, but it cannot bear the responsibility of its decisions. It cannot understand love, compassion, or the full depth of human values.

Although this blog post was written with the help of AI, every idea, every reference, and every word choice were mine—carefully revised and refined to reflect my own voice. As my father told me: “To give up thinking is to give up freedom.” In an age dominated by algorithms, keeping our minds sharp isn’t just a personal choice. It’s our last line of defense for human dignity and life.

figure 6: Who make final decision?

References:

Althusser, L. (1971). Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. In L. Althusser (Ed.), Lenin and philosophy and other essays (pp. 85–126). Monthly Review Press.

Baker, P. (2019, July 16). I think this guy is, like, passed out in his Tesla. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/16/magazine/tesla-autopilot-crashes.html

Barbrook, R., & Cameron, A. (1996). The Californian ideology. Science as Culture, 6(1), 44–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505439609526455

Bogert, E., Schecter, A., & Watson, R. T. (2021). Humans rely more on algorithms than social influence as a task becomes more difficult. Scientific Reports, 11, Article 8028. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87584-5

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. J. Boczkowski, & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society (pp. 167–194). MIT Press.

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage.

McChesney, R. W. (2013). Digital disconnect: How capitalism is turning the Internet against democracy. The New Press.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

Smythe, D. W. (1977). Communications: Blindspot of Western Marxism. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory, 1(3), 1–27.

Uzair, M. (2021). Who is liable when a driverless car crashes? World Electric Vehicle Journal, 12(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020062

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment