Introduction: When Tate comes back with his hate speech

‘Women are men’s property’. This is what Andrew Tate said on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and YouTube. He is a British-American former kickboxer and reality television star, who is also notorious for his aggressively misogynistic rhetoric. He posts some disturbing views on insulting and abusing women with millions of social media followers, including an extensive range of teenagers.

As a result, multiple social platforms banned him for spreading hate speech about gender. However, Elon Musk reinstated Tate’s account on Twitter(X) in the name of ‘Free Speech’, which entitles everyone to express their opinions on the platform.

But when a person harms others while exercising their right to freedom of speech, should the platform also protect them? By doing this, is the platform protecting people’s freedom of speech, or is it indulging the hate speech of some individuals?

This blog will use Tate’s return as a case study to explore how digital platforms, especially Twitter, amplify hate speech and online harms in the name of free speech.

What is Hate Speech and Online Harm?

What is ‘Hate Speech’? Bhikhu Parekh (2006) offers a definition that it is the ‘speech that expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation’.

Although hate speech is often violent and emotional, language itself does not incite public violence. Parekh (2006) further identifies its three key features that it is directly against a group based on irrelevant features, stigmatizes the target group with highly undesirable qualities, views them as an unwelcome presence, and ultimately positions them as a legitimate object of hostility.

It will exacerbate mistrust and hostility in the society and deprive the human dignity of the targeted groups. As a consequence, victims find it difficult not only to participate in the collective life, but also lead autonomous and fulfilling personal lives.

As Carlson and Frazer (2018) observe in their research on Indigenous Australians, local people who participated in this research describe social media that operated not within a neutral space, but a multi-layered terrain of cultural beliefs and practices, community relationships, hostile interactions and exposure to harmful materials. Under such unequal backgrounds, hate speech based on racism can not only cause verbal abuse but also discrimination, marginalization, and even escalate to problems in the real world, such as personal safety issues.

Meanwhile, Brison (1998) suggests that ‘verbal assaults’ can cause ‘psychic wounds’, constituting continuous and long-term injury.

These harms may not always be visible, but they are real and actually harm the physical and mental health of victims and even affect their normal life.

Based on these, we can now turn to see the case of Andrew Tate and ask: Do his arguments belong to hate speech?

Andrew Tate: Disguised Misogyny on platforms

Andrew Tate was a British-American kickboxer and reality television star with millions of social media followers. Meanwhile, he is also ‘absolutely a misogynist’ and labels himself as an ‘alpha male’. ‘Alpha male’ is to promote dominance, control, emotional detachment and misogyny in digital masculinity cultures. His words are often filled with verbal abuse, violence and contempt for the autonomy and other rights of women.

‘Women belong in the home, can’t drive, and are a man’s property.’

‘My woman obeys me. She has to.’

‘If you’re not gonna listen to your man… what are you with him for? To argue?’

These arguments regarded women as someone who should be controlled by nature and obey men, and devalued women as a whole based on gender, which is completely consistent with the first characteristic of hate speech Parekh proposed–‘identity attack’.

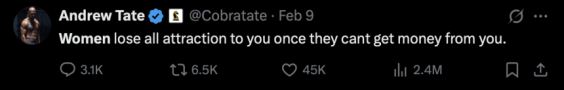

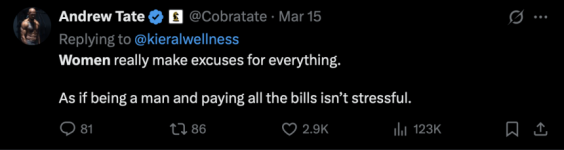

Through the tweets, comments, videos and interviews, Tate always stigmatizes women just like the second feature of hate speech, and labels women’s normal participation in social activities, expression of emotions, and pursuit of freedom as unfaithful, greedy and fickle.

Even more worrying is Tate’s promotion of violence.

“It’s bang out the machete, boom in her face, you grip her up by the neck, ‘WHAT’S UP BITCH’.”

Tate even posts instructional videos online and guides followers to attend his paid courses ‘Hustler’s University’ and ‘War Room’. During the lessons, he teaches followers to respond to women with verbal abuse and violence when accused of cheating. Such arguments advocate violence and may even induce others to imitate. It aligns with Brison’s concept of ‘verbal assaults’, which may lead to psychic wounds of fear of men and even long-term harm for women.

Source: Pexels (Photographer: Kaboompics.com)

Beyond physical control and violence against women, Tate even attempts to deprive women of their political rights.

‘Women shouldn’t be allowed to vote. All of the world’s problems go away.’

He attributes the world’s problems to women’s participation in politics, attempting to justify hostility and exclusion toward women.

More worse, Tate’s misogyny was not only tolerated but also repackaged and amplified by his followers. His content was edited by a large number of fans with popular music and memes, spreading rapidly and widely on social platforms with 11.6 billion times viewed. Just like Matamoros-Fernández (2017) observes, hate speech was cloaked via humor to avoid detection. This mode may not directly mention or involve misogyny, but rather hide it behind humor, making it normal and difficult to detect.

Platform Amplification and Culture — Twitter (X)

In 2022, after being unanimously boycotted by the majority of netizens, platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube banned Andrew Tate for promoting hate speech–misogyny. On the contrary, Twitter (X) under the leadership of Elon Musk restored Tate’s account later in the name of ‘free speech’. It represents the public and clear attitude and stance of Twitter for granting hate speech visibility and legitimacy, effectively reinstating the influence of Tate on social platforms.

The rapid resurgence and spread of his misogynistic content can be largely attributed to the algorithmic recommendation mechanism of the platform–Twitter. The algorithm will take priority of content with high interaction (likes, comments and shares) rather than high-quality content. However, extreme speech, sensational posts and controversial opinions are more likely to trigger emotional reactions, identified as ‘high engagement’ by the algorithm. As Bucher and Helmond (2017) argue, platforms adapt their interfaces to users largely based on economic interests.

Even worse, Musk launched the ‘Content Creator Sharing’ plan. According to this plan, users can monetize through views and interactions. Under such conditions, extreme speech and aggressive content are not only allowed but also rewarded. There is no doubt that Tate’s content is so extreme that aligns with these features and the commercial model mentioned above very well.

However, the algorithm does not operate neutrally. According to Matamoros-Fernández (2017) and Massanari (2015), platforms import popular cultural biases into the algorithm, producing and amplifying platform racism and toxic technocultures, and shaping unique platform culture.

To sum up, such transformations of Twitter’s algorithm have not only weakened the ethical responsibility of platforms but also formed distinctive platform cultures. Influenced by this platform culture, users are allowed to spread hate speech with few barriers, protected in the name of ‘free speech’. It is the platform that amplifies hate speech, which may also trigger a question about the ethical responsibility of platforms.

Free Speech Is Not Freedom to Harm: Platform Moderation and Responsibility

Although the algorithm of Twitter amplifies and accelerates the spread of hate speech, the new regulatory rules of free speech under the leadership of Elon Musk play a greater role. He disbanded the ‘Trust and Safety Council’ and laid off a large number of content review team members, further weakening the protection of users. It leaves a loose moderation system heavily relying on the algorithm with significantly reduced human review. However, Roberts (2019) argues that most of the social media content uploaded needs human intervention to be appropriately screened, especially videos and images.

As Roberts said, this paradigm was a business decision on the part of the social media corporations themselves instead of technological necessity or other factors. With loose moderation only based on the algorithm, Twitter has restored previously banned accounts, such as Tate’s, despite their hate speech in the past. In doing so, Twitter has increased the risks of hate speech to a large extent with a 50% rise in hate speech and 70% more likes, placing its commitment to openness above user safety.

According to Article 19 of the UDHR, free speech means that everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without inference and freedom of expression, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas regardless of the kinds of media in the world. However, this right is not unlimited. ICCPR later amends this by stating that the exercise of these rights may be subject to certain restrictions in order to respect others’ rights and reputation and maintain public order. Therefore, free speech is not absolute, particularly when it infringes on others’ dignity.

Just like Massanari (2015) said in her analysis of Reddit, platform cultures are often saturated with a rhetoric of ‘freedom’ that conceals structural power and facilitates the spread of hate.” It applies to Twitter very well, where claims free speech against moderation and indulging hate speech are not actually maintaining the rights of free speech, but to attain currency and profits from great influence.

It is platforms that have both the right and the responsibility to moderate content that is likely to pose clear harm to users, especially young people and vulnerable groups. Protecting the rights of free speech cannot be at the expense of harming others’ dignity and safety. Platforms must make strict moderation policies with strict implementation and effective implementation.

Platform Governance Is a Choice: Twitter & Meta, YouTube

Not all platforms condone Tate’s hate speech. Twitter has reinstated his account in the name of free speech, while Meta (including Facebook and Instagram) and YouTube have banned his account decisively, forming a sharp contrast.

Regarding Tate’s hate speech, contrary to Twitter, Meta has taken surprisingly swift and decisive action to ban his accounts on both Facebook and Instagram due to violating the policies of the platforms about hate speech and dangerous individuals. Then, YouTube also terminated Tate’s channel for the same reason, deleted multiple videos related to him and banned him from uploading content through other channels, prohibiting him from all aspects and channels. Unlike Twitter, these platforms have the same attitude towards Tate’s hate speech–intolerance.

When comparing how platforms handle the amplification of their algorithm of themselves, the contrast is more obvious. On Twitter, Tate’s content can be allowed to spread with loose moderation, only based on the algorithm that prioritizes high engagement and controversy rather than any ethical consideration. He can even make profits from the ‘Content Creator Sharing’ plan of the platform. On the contrary, Meta and YouTube use similar mechanisms, combining human review and artificial intelligence to identify and remove content that violates the standards of the platforms. Moreover, Meta uses the algorithm to reduce the visibility of illegal content, effectively limiting its spread to a large extent.

These decisions reflect not only the direct attitudes of platforms but also their different governance philosophies. Twitter advocates free speech only depended on the currency and high engagement, even at the cost of harming users. In contrast, Meta and YouTube consider more about ethical responsibility and public order that they aim to create communities with diversity, inclusion and respect, based on protecting user safety.

Platforms are not neutral in that they shape public discourse by the content they allow, ignore and delete. How to govern the public discourse is the choice of platforms. Twitter chose the reach, while Meta and YouTube chose the ethical responsibility.

Conclusion: Governing Hate, Preventing Harm

The case of Andrew Tate’s account reinstated on Twitter is a typical and meaningful case study of not only how platforms amplify hate speech, but also how the algorithm and governance choices influence the spread of hate speech.

Twitter has decided to restore Tate’s account in the name of free speech, mostly to make profits by his influence, seeming like a neutral stance. It allows hate speech to spread without any restrictions, making it normal and legal and representing the online harm of hate speech. Unlike Twitter, Meta and YouTube removed Tate’s content and conducted strict ethical moderation, taking priority on user safety rather than economic benefits.

Actually, these different decisions and outcomes are not driven only by techniques–the algorithm, but more by the governance values of the platforms. With the rapid speed of spread on platforms, platform governance is essential that platforms should take the corresponding responsibility to review ethical aspects and protect both the rights of free speech and the safety of users, especially regarding hate speech.

References

Brison, S. J. (1998). Speech, harm, and the duties of authors. In J. Cohen & F. D. Miller Jr. (Eds.), Liberalism and its practice (pp. 127–144). Routledge.

Bucher, T., & Helmond, A. (2017). The affordances of social media platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 233–253). SAGE Publications.

Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2018). Social media mob: Indigenous people and online hate in Australia. Macquarie University. https://research.mq.edu.au/

Massanari, A. (2015). Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1290129

Parekh, B. (2006). Hate speech. In A new politics of identity: Political principles for an interdependent world (pp. 40–60). Palgrave Macmillan.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media. Yale University Press.

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Freedom of speech. Wikipedia. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_speech

Be the first to comment