Introduction

Have you ever experienced the following situations in your life: when you go to a restaurant and want to order online, the system asks you to provide information such as your mobile phone number. When you chat with a friend online, you mention an item, and when you open another social media app, you see an advertisement for the related item? This often makes people feel that their privacy is being peeped. On digital platforms, privacy is no longer limited to the content we actively share. In this world full of complex algorithms and usage agreements, we must regard privacy as a public and political issue, not just a personal issue (Nissenbaum, 2010; Suzor, 2019).

What is privacy? How has it changed on digital platforms?

Privacy is usually understood as people’s right to control their personal information. In the past, this meant that we could decide who could see our letters, photos or conversations. But today, privacy has become more complicated. Data is collected almost every moment on digital platforms, such as liking a piece of content, turning on location or clicking a link, and the behavior behind it may also be tracked and recorded. And many times, this tracking and recording is not clearly authorized.

Digital privacy is not only about what we actively share, but also about how the data is collected, for what purpose, and whether we have real choices. As Nissenbaum (2010) proposed, “contextual integrity” means that privacy depends on whether the data is shared in the right social context. But these contexts are often intentionally disrupted by the platform, making it easier for the platform to expand data collection and more difficult for users to protect themselves.

Therefore, many scholars believe that privacy is no longer just a personal issue, it also involves the distribution of power, the principle of fairness and institutional transparency. Survey data from Flew, Martin and Suzor (2019) show that although many users say they care about privacy, most admit that they do not know how to effectively protect it. For example, many people feel uneasy when seeing personalized ads and are concerned about their data being tracked, but few actually change their privacy settings, use encrypted apps, or read user agreements carefully. This shows that a real problem is that caring about privacy does not mean being able to protect it.

What are some common privacy violations in life?

In modern life, many privacy violations are very common, but they involve complex data collection mechanisms and unequal technical power structures. Here are some common scenarios:

First, many platforms collect unnecessary data by default. Many social or life apps, such as XiaoHongShu and WeChat, obtain location, photo album, microphone and other permissions without the user’s knowledge or understanding (Suzor, 2019). In addition, users often inadvertently agree to vague terms in long user agreements, thereby authorizing the platform to collect and use information beyond the expected scope.

Another common thing is the personalized recommendations of many platforms. The platform tracks user behavior and pushes content through algorithms. The classic example is TikTok, which builds data portraits through users’ viewing, liking and staying behaviors, and controls the content that appears in front of users based on this, and even hides the voices of specific groups (Zuboff, 2019; Pasquale, 2015). These algorithmic decisions often lack transparency, and users cannot understand the specific logic and rules behind them.

The third point is that users lack the right to know and negotiate privacy rules. When you use a software, you see a long user agreement that pops up. Have you really read it carefully? In fact, most people do not understand the terms in the service agreement and cannot change the rules. Even if they notice that their privacy has been violated, it is difficult to find a place to complain or appeal (Marwick & boyd, 2018; Karppinen, 2016).

In addition, the collected data can be abused for commercial or surveillance purposes. For example, a photo sent to a friend may be used by the platform for advertising. A location-based use may be recorded and sold to a third party. This kind of contextual destruction is a typical manifestation of the destruction of situational integrity proposed by Nissenbaum (2010).

As Flew, Martin and Suzor (2019) pointed out, although more and more people express concern about privacy, they find it difficult to truly protect themselves due to a lack of relevant knowledge or tools. These realities show that privacy violations in the digital age are often structural, systematic and difficult to see.

Why are privacy and digital rights important?

Many people think that their privacy is important, but in the digital age, privacy is more important than we think. Why? In the digital age, privacy and electronic rights are not just about whether individuals have something to hide. The process of collecting, analyzing and using our data by the platform constitutes an invisible governance that affects our rights to access information, express opinions and participate in social life (Nissenbaum, 2010; Zuboff, 2019).

The core of privacy is not just data security, but human dignity, freedom and right to choose. When we cannot control when, how and who uses our data, we lose control of our own narrative and identity (Marwick & boyd, 2018). This not only puts ordinary users at a disadvantage, but also constitutes unequal structural harm to marginalized groups such as LGBTQ.

The importance of electronic rights lies in that they define whether we can surf the Internet safely, speak freely and be treated fairly in the online world. Karppinen (2016) pointed out that digital rights should be viewed as part of human rights, otherwise platforms will continue to deepen control and opacity in the name of technological neutrality. And Suzor (2019) pointed out that we live under a set of invisible rules today, which are neither democratically negotiated nor accountable. Redefining privacy and digital rights is not just a legal fix, but also a reconstruction of fairness and justice in the digital society.

Case analysis

In recent years, with the rise of artificial intelligence, many electronic platforms have begun to add artificial intelligence-related content to their systems. However, several mainstream platforms have updated their user agreements without the explicit consent of users, and used the content posted by users for the training of artificial intelligence models, which has aroused widespread attention and controversy.

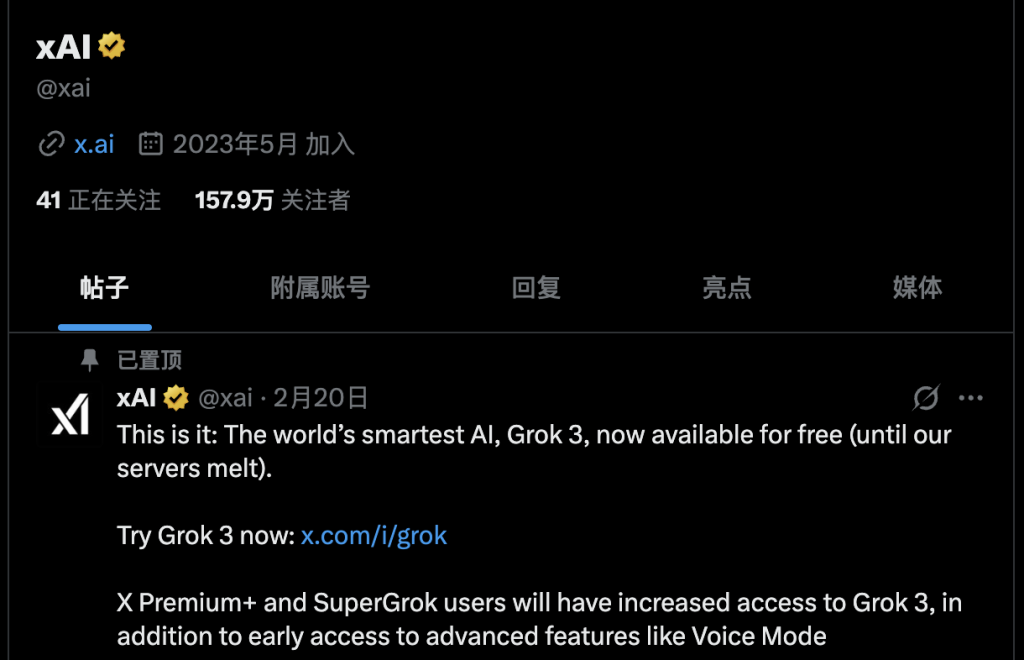

The first example is Twitter. Twitter, now known as X, is a world-renowned social media platform that allows users to post short messages of up to 280 characters and interact in real time through likes, reposts, tags, etc. It has more than 300 million active users worldwide, especially in the fields of politics, news, social movements and celebrity culture. After Elon Musk acquired it, the platform was renamed “X” and plans to expand into a multi-functional platform covering payment, AI and content creation (Sohu News, 2023).

In October 2024, the X platform updated its privacy policy, stipulating that any content posted by users, including text, pictures, audio and video, will be used to train AI models, and the platform has a royalty-free license to users’ content. This change was implemented without explicit notification to users and assumed user consent, leading to a large number of creators deleting their works or canceling their accounts in protest (Sohu News, 2023).

A similar case is Xiaohongshu (red book), a popular Chinese social media and e-commerce platform that combines content sharing with consumer recommendation functions. Users can post notes, including pictures, texts or short videos. Xiaohongshu has more than 200 million monthly active users in China, especially among young women and urban consumer groups. It is not only a platform for sharing lifestyle content, but also increasingly becoming an important channel for brand marketing, aesthetic communication and trend guidance. (Chongqing News Net, 2024).

Recently, Xiaohongshu was exposed for using user-posted content to train its AI model without explicitly notifying users, which has aroused widespread attention and controversy (Chongqing News Net, 2024). Xiaohongshu’s user agreement contains a clause that authorizes the platform to “use user content free of charge, irrevocably, non-exclusively, and without geographical restrictions, including the creation of derivative works.” This clause has been interpreted as allowing the platform to use user-posted content for AI training without the user’s explicit consent. In addition, Xiaohongshu has also launched the AI painting tool Trik, which has been accused of using users’ original works for training without authorization. Many illustrators found that the works generated by Trik were highly similar to their original works in style and composition, and suspected that their works were used for AI training. After discovering that their works may have been used for AI training, many illustrators filed a lawsuit against Xiaohongshu, accusing it of infringing their copyright and privacy rights by using user content for AI training without authorization. In order to express their opposition, many users posted a statement in the post that their content was not authorized to the platform. However, this statement did not prevent the platform from collecting user information. Some users were surprised to find that the AI on the platform would also put this non-authorization statement when summarizing their account information. Many users also chose to cancel their accounts in anger to express their protest, but as more and more platforms introduce AI functions, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find a platform that does not collect user information for AI training.

These incidents show that more and more platforms are blurring the boundaries of user consent. The default of user content being used for AI training reflects the absence of privacy protection in reality and the opacity of the system.

Different countries have come up with different solutions to protect digital privacy

Comparison of digital privacy laws in Europe, China and Australia:

In 2018, Europe introduced the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which is widely regarded as one of the strongest data privacy laws. It gives users the right to access, modify, delete and transfer data. Companies must explain the purpose of data, obtain explicit consent, and report data breaches within 72 hours (European Union, 2016). In practice, GDPR has imposed huge fines on companies such as Meta and Google. But at the same time, some critics point out that its enforcement in small companies and cross-border cases is still problematic.

In China, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) was implemented in 2021. The law clarifies the requirements for data collection, storage and cross-border transfer, including stronger user consent mechanisms and data minimization principles. Companies are required to set up data protection officers and conduct risk assessments before cross-border transfers (Liu, 2022). In terms of shortcomings, some people criticize that the law does not restrict the country’s access to data. Karppinen (2016) pointed out that legal reform should be promoted together with institutional transparency and public trust.

In Australia, the Privacy Act 1988 is currently being revised. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is working to improve enforcement. However, Goggin, Humphry, and Wilken (2017) believe that privacy protection in Australia is still mainly “passive response” and many users are not aware of their rights.

These comparisons show that the awareness of electronic rights and privacy in the world is constantly increasing, and many countries have introduced laws and regulations to protect them. However, there are still problems such as high difficulty in enforcement and room for large companies to circumvent.

Conclusion:

On digital platforms, privacy is no longer a personal choice that we can control, but a structural problem dominated by platform rules, algorithms and commercial interests. From the hidden data collection of WeChat and XiaoHongShu, to the algorithm recommendation of TikTok, to the controversy of X platform and Xiaohongshu using user content to train AI, we can find that users are excluded from important decisions, but bear real privacy risks.

By analyzing the comparison of privacy laws in different countries, it can also be seen that truly effective privacy protection requires not only legislation, but also institutional transparency, user education and platform responsibility.

In the digital society, privacy is not only about what we publish, but also about whether we have the right to decide how to be treated. We need a more fair, open and user-respecting technical environment, rather than just accepting the reality of established rules.

Reference:

1. Chongqing News Net. (2024, March 22). Xiaohongshu’s AI product accused of training on user content; illustrators file lawsuit. Retrieved from https://news.cqnews.net/1/detail/1181504390185254912/web/content_1181504390185254912.html

2. European Union. (2016). General Data Protection Regulation. Retrieved from https://gdpr.eu

3. Flew, T., Martin, F., & Suzor, N. (2019). Internet governance and regulation. In T. Flew (Ed.), Understanding Global Media (pp. 199–215). Palgrave Macmillan.

4. Goggin, G., Humphry, J., & Wilken, R. (2017). Digital rights in Australia. University of Sydney.

5. Karppinen, K. (2016). Human rights and the digital. In C. T. McGarry & M. McLoughlin (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights(pp. 220–229). Routledge.

6. Liu, H. (2022). Understanding China’s Personal Information Protection Law. Asia Pacific Journal of Law and Society, 3(2), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/apj.2022.11

7. Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2018). Understanding privacy at the margins. International Journal of Communication, 12, 1157–1165.

8. Nissenbaum, H. (2010). Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford University Press.

9. Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

10. Sohu News. (2023, September 4). X platform accused of using user content to train AI; creators respond by deleting posts. Retrieved from https://www.sohu.com/a/820585406_121138510

11. Suzor, N. (2019). Lawless: The secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge University Press.

12. Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

Be the first to comment