Figure 1: People are calling for a revolt against Asian hate. From Covid ‘hate crimes’ against Asian Americans on rise by Getty Images, 2021, BBC News (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684). Copyright 2024 BBC.

Have you ever seen discriminatory terms such as “Chinese Virus” or “Wuhan Virus” on social media or in real life during COVID-19? Have you noticed an exponential increase in attacks against Asian Americans across the United States because of these xenophobic comments?

Introduction

The Internet and social media platforms have created a space where everyone can communicate freely, and users can even express themselves anonymously. It is therefore impossible to avoid the existence of harmful hate speech, and social media may accelerate its dissemination.

Hate speech is defined as offensive speech posted by a person who is prejudiced towards a group of people and intends to encourage, incite or provoke hatred against them (Mondal et al., 2017; Flew, 2021). It should be noted, however, that a distinction should be made between hate speech, which is extremely harmful and needs to be regulated, and general insulting speech (Sinpeng et al., 2021), as everyone’s basic right to freedom of expression should be protected even though these words may be offensive to others. It was found by Mondal et al. (2017) that hate speech on mainstream social media platforms is primarily related to race, behavior and physical, with these categories accounting for close to 90% on Twitter. In this online context of massive hate messages, users can easily be influenced to take actions in the real world that could harm specific groups of individuals.

Case Study: Anti-Asian surge during COVID-19

COVID-19 is a highly contagious respiratory disease that was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. It spread worldwide in just a few months, killing millions of people and severely disrupting economies, education and social stability.

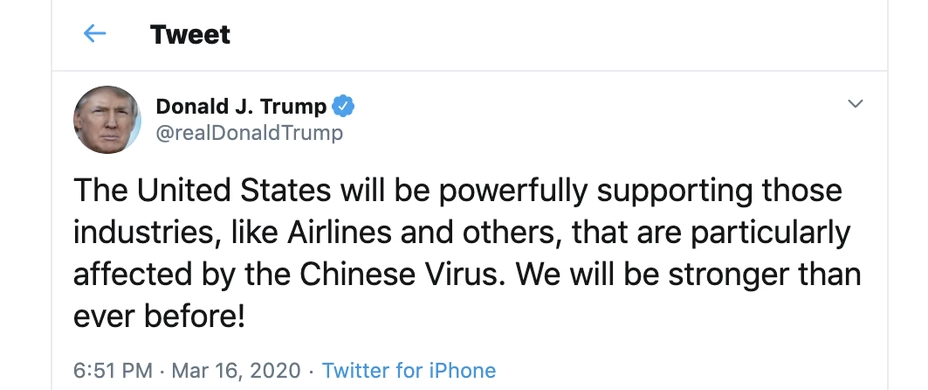

Due to the extreme negative impact COVID-19 has caused on daily life, some Americans have begun to blame China for the virus as it was first found in China and have called it the “Chinese Virus” or the “Wuhan Virus” on social media. Hatred against Asians within the United States increased rapidly, especially when former U.S. President Donald Trump referred to the coronavirus as “kung flu” in a public speech in Phoenix, as well as tweeting about the “Chinese virus” (Figure 2).

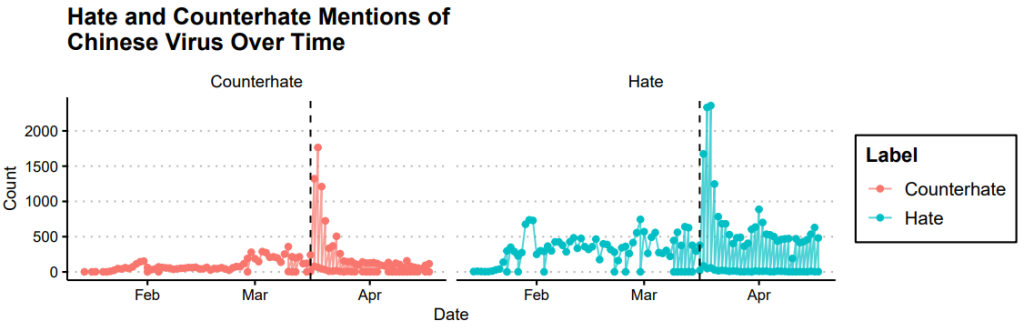

In addition to this, other officials such as Congressman Paul Gosar and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have also used these terms in public, and an 800% increase in such rhetoric in the conservative media by March 9, 2020 (Yam, 2020). According to Kim and Kesari (2021), both hate and anti-hate speech from U.S. Twitter users have surged exponentially due to Trump’s anti-Asian tweet (Figure 3). Therefore, Yam (2020) stated that while anti-Asian attitudes have gradually declined in recent years, these celebrity behaviors have reversed the trend in a few days.

These speeches by U.S. officials and media fit several characteristics of hate speech that should be controlled, such as occurring in a public space, targeting members of marginalized groups in the social environment, and the speaker having certain formal authority (Sinpeng et al., 2021). They blame Chinese and even Asian Americans for the creation and spread of the coronavirus by stigmatizing them as legitimate targets of hostility and implying that they are destabilizing society, and thus may have to be legally eliminated or deported for the development of a better society (Parekh, 2012). In this case, not satisfied with just abusing Asians on social media platforms, some Americans affected by hate speech have, more terribly, begun attacking and victimizing Asians in the real world, threatening to drive them out of the United States.

Stop AAPI Hate, a reporting center dedicated to addressing racism and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AA and PI), showed that a total of 9,081 incidents of hateful behavior were reported from 2020 to 2021, of which 63.7% were verbal harassment and 15% were deliberate avoidance (Braun, 2021). For example, an eighth-grader student from Chesterfield said “I was harassed for being Chinese. I was repeatedly told to ‘f*** off the planet with my viruses’ and that I equaled the virus” (Braun, 2021). It can be seen that such hate speech associates him with the nasty virus and insults him as not an equal member of society.

Even worse than verbalized hate speech is the transfer of hatred into physical action. It was mentioned by Yam (2021) that a report from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism showed that while the overall number of hate crimes in 16 U.S. cities declined by 7 percent, hate crimes against Asian Americans spiked by nearly 150 percent. Cabral (2021) listed a number of attacks on Asians during this period, for instance, an unidentified assailant in New York City hit an Asian American woman in the head with a hammer and demanded she take off her mask. These horrific data and incidents illustrate the significant negative impact of hate speech. However, Sherman (2021) pointed out that the amount of hate crimes is underestimated and that these numbers may only be a portion of the actual incidents because Asian Americans may not report being hurt for various reasons such as fear of retaliation, language or cultural barriers and lack of trust in the police.

The destructive consequences of hate speech

Physical and psychological injuries to the victim

Parekh (2012) indicated that the intimidation of hate speech affects the normal life of the target group and keeps them in a constant state of fear. As shown in the video by BBC News (2021, 1:23), the woman threatened by the hate speech wore a hat, sunglasses and a mask for the interview because she did not want to reveal her identity and endanger her children. Living in such racially discriminatory environments over a long period of time may lead to harmful psychosocial stress and thus have a negative impact on physical health (Yam, 2020). In addition, individuals affected by hate speech can also be seen in the video (BBC News, 2021) attacking Asians in real life, pushing them down or slashing them with knives. These hate crimes not only bring physical harm to the victims, but they may also cause incalculable damage to their mental health, family members, and finances.

Negative social impacts

First of all, hate speech can hinder shared community life and promote discrimination and marginalization. Hate speech is usually an exclusionary, insulting and offensive expression that deepens mistrust and hostility between people and undermines the value of mutual respect in collective life (Parekh, 2012; Flew, 2021). For example, those who said that the eighth-grade student was equal to the virus, as mentioned above, were not only stigmatizing him but essentially disrespecting him and denying his human dignity. In this case, victims may be unwilling to participate in a collective life that is hostile to them and unable to trust others.

Additionally, hate speech can, to a certain extent, lead to serious social polarization and undermine social cohesion. Kim and Kesari (2021) found that Trump’s anti-Asian tweets caused heated debates between hate speech advocates and anti-hate speech advocates, exacerbating tensions between them. This phenomenon can deepen existing internal divisions and is not conducive to stable social development.

Furthermore, Parekh (2012) believed that allowing the spread of hate speech would make the targeted groups feel that the State had neglected their dignity and rights, thereby depriving the State of its authority and legitimacy in their minds. Therefore, receiving hate speech over time can lead to increasing distrust of the targeted minorities towards society and the nation. As Parekh (2012) noted, the important thing is not the consequences of hate speech disrupting public order but its broader long-term impact on marginalized groups and society.

Deterioration of relations between countries

One of the most serious negative effects of hate speech is that it can affect diplomatic relations between certain countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian speakers argued that China created the virus and tried to shift the responsibility, so they attempted to accuse China by calling the virus as “Chinese virus” (Kim & Kesari, 2021). The widespread dissemination of false information through social media platforms has led to a shift in the attitudes of many Americans towards Asians, resulting in increased discrimination and violence (Yam, 2021). Such stigmatization has undoubtedly caused resentment among the government and people of China, who have criticized these speeches as racist and xenophobic. This has to some extent caused tension between the two countries, affecting further cultural communication, economic and technological cooperation between them.

Why and how should hate speech be governed?

When thinking about how to regulate hate speech, one issue that must be considered is freedom of speech. It is the foundation of an equal and meaningful life for human beings, and a necessary condition for being able to drive progressive development in the political and academic spheres and ensure the free flow of information (Parekh, 2012).

Meanwhile, Parekh (2012) also argued that any right should be based on a moral community and be governed by certain regulations in order to ensure the basic interests of all members. Everyone has the right to freedom of speech, especially when social media allows for anonymity, some users are more likely to express their negative feelings that have been suppressed in reality (Mondal et al., 2017), which may include hate speech. Since hate speech promotes hostility and discrimination against individuals or minorities, it should not be protected by freedom of expression as it is aimed at insulting and degrading others and disrupting public order in society. In other words, whether online or offline, in words or images, hate speech should be strictly regulated and controlled.

Hate speech can be governed in the following ways simultaneously. Regarding hate speech on social media platforms, Mondal et al. (2017) suggested strengthening online identity verification and adopting stricter content moderation rules for anonymous posts. The advantage of this is that individuals will need to consider the risk of their real identity being revealed before they post or comment, thus reducing negative messages sent on impulse. In addition, hate speech can be regulated through the establishment of treaty documents or through legal means. For instance, the United Nations secretary, Anthonio Gutteres, signed a document titled “United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech” in 2019, committing to collaborate with traditional and new media to detect and analyze hate speech and promote social cohesion and national security (Agwuocha, 2021). Another example of addressing hate speech and crime is President Biden’s signing of the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, which banned the use of terms such as “kung flu” in the federal government (Cabral, 2021).

While these measures can be effective in controlling and minimizing hate speech, they still cannot reach the root of the problem in changing the minds of individuals who are convinced by disinformation and stereotypes. For this reason, it makes sense to add accurate information about the culture and history of Asians to educational courses, which can promote cross-cultural communication and understanding between races and increase diversity and inclusion.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article discussed the negative consequences of hate speech in our world through the case of the anti-Asian surge in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. It can be seen that hate speech not only appears in textual form on the Internet to harm the victim’s mental health, but it can also turn into real-world hate crime incidents that threaten human lives. In either form, hate speech can have extremely adverse impacts on the lives of individuals, the stability of societies and the diplomacy of nations, therefore, hate speech must be regulated. Language is the bridge of human communication, on which our relationships are built and information is disseminated. It should not be misused to discriminate against others or to incite violence. Only by realizing the responsibility that comes with freedom of speech can we build a world of mutual respect and inclusion, with cultural and racial diversity.

References

Agwuocha, U. A. (2021). COVID-19 induced hate speech and Austin’s speech act theory perspective: Implications for peace building. Proceedings of the International Conference of the Association for the Promotion of African Studies on African Ideologies, Human Security and Peace Building, 10th -11th June 2020. The Association for the Promotion of African Studies, pp. 159-182.

AP Photo. (2021). Hate crimes against Asian Americans: What the numbers show, and don’t. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2021/hate-crimes-against-asian-americans-what-the-numbers-show-and-dont/

BBC News. (2021, March 20). Anti-Asian violence in the US: ‘He slashed me from cheek-to-cheek’ – BBC News [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NcrXOyRncIM

Braun, S. (2021, August 12). Statement: New data shows that Asian Americans remain under attack — Over 9,000 Anti-Asian incidents reported. Stop AAPI Hate. https://stopaapihate.org/2021/08/12/stop-aapi-hate-national-report-3/

Cabral, S. (2021, May 21). Covid “hate crimes” against Asian Americans on rise. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Getty Images. (2021). Covid “hate crimes” against Asian Americans on rise. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56218684

Kim, J. Y., & Kesari, A. (2021). Misinformation and hate speech: The case of anti-Asian hate speech during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i1.13

Mondal, M., Silva, L. A., & Benevenuto, F. (2017). A measurement study of hate speech in social media. Proceedings of the 28th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, HT 2017, Prague, Czech Republic, July 4-7, 2017. Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 85-94.

Parekh, B. (2012). Is there a case for banning hate speech? In M. Herz and P. Molnar (Eds.), The Content and Context of Hate Speech: Rethinking Regulation and Responses (pp. 37–56). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sherman, A. (2021, March 22). Hate crimes against Asian Americans: What the numbers show, and don’t. Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2021/hate-crimes-against-asian-americans-what-the-numbers-show-and-dont/

Sinpeng, A., Martin, F. R., Gelber, K., & Shields, K. (2021). Facebook: Regulating hate speech in the Asia Pacific. Department of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney, and The School of Political Science and International Studies, The University of Queensland. Retrieved from https://r2pasiapacific.org/files/7099/2021_Facebook_hate_speech_Asia_report.pdf

Yam, K. (2020, September 30). Anti-Asian bias rose after media, officials used “China virus,” report shows. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/anti-asian-bias-rose-after-media-officials-used-china-virus-n1241364

Yam, K. (2021, March 10). Anti-Asian hate crimes increased by nearly 150% in 2020, mostly in N.Y. and L.A., new report says. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/anti-asian-hate-crimes-increased-nearly-150-2020-mostly-n-n1260264

Be the first to comment