Who is thinking: Human or AI?

With the development of science and technology, AI algorithms have gradually penetrated individuals’ lives and been used in all aspects, significantly changing people’s lifestyles. Algorithms are rules and processes established for activities such as calculation, data processing, and automatic reasoning (Terry Flew, 2021) and are the basis for realizing AI functions. Therefore, it can help people simulate cognitive functions like learning, understanding texts, recognizing pictures, etc. Then, provide people with a more convenient and faster living and learning environment.

AI does not emerge from anything but learns experiences from users’ repeated interaction behavior and continuously improves the data over time to better respond to user needs and even predict potential risks (Terry Flew, 2021). This means that the AI algorithm cannot create knowledge on its own. It must rely on repeated learning of the knowledge or skills experienced and mastered by humans to respond to people’s input. Compared with AI’s powerful integration ability, humans’ learning ability is relatively limited. It is difficult for humans to master all fields of knowledge quickly. Therefore, people increasingly rely on artificial intelligence for fast and accurate decision-making, enjoying almost error-free “answers” and significantly improving efficiency in problem-solving. However, when humans rely too heavily on artificial intelligence, they may fail to recognize its shortcomings, creating a false sense of security (Green, 2021).

In the following sections, I will discuss three points: The potential cost-overdependence of AI algorithms for people in bringing convenience. Challenges in the governance of AI algorithms. Thoughts on the future of AI governance.

Education and AI: Rampant Fraud on Campus

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been used in academia since its development, providing convenience and quick access to information in the education sector. It has also increased concerns about student fraud and other breaches of academic integrity. Chatgpt, an AI tool launched in 2021, has a primary function that includes generating human-like text and interacting with human beings in conversations to help people solve problems practically. In addition, it has over 175 billion parameters, making it one of the most significant language models currently available in the world (Transformer et al., 2022). Since its release, Chatgpt has been known for accurately and quickly performing various linguistic tasks, such as translating text, content generation, and language modeling. These advantages also bring benefits to the education field, such as improving student participation and motivation (Cotton et al.) Therefore, at the beginning, Chatgpt emerged for positive purposes, but due to people’s unreasonable usage, it brought a series of challenges to the education field.

In 2023, two philosophy professors at Feynman University believed that an essay submitted by one of their students was generated using AI. The student’s essay was overly perfect, including complex use of grammar, an unblemished level of thinking, and paper structure. However, the content of the essay was incredibly empty, without context or depth, and some of the statements in the content were even completely wrong. When the professors ran the article through an AI detector, they found a 99% chance that it was written by an AI (Nolan, 2023).

Philosopher David Hume said that “the presence of mistakes in true perfection is the most dangerous signal.” Chatgpt generates content based on original training knowledge without learning other examples. This also means that it can write seemingly convincing content, even a complete book, without any basis, even if the description is primarily illogical (Dehouche, 2021).

Article generated by Chatgpt-3.5(Dehouche, 2021)

When testing the content of the AI against examples from Chomsky’s linguistics, people will find that Chatgpt generates one semantically repetitive sentence out of every ten and that specific sentences are contradictory. For example: “Once you have lost something, you do not have it anymore” (Chomsky, 1965). In contrast, a student needs to think open-mindedly while learning multiple subject aspects and reasonably critique the original knowledge or future trends. Nevertheless, AI is not capable of autonomous thought and innovation. AI’s “thinking behavior” depends entirely on human-created knowledge. The answers it gives after discussions with humans are primarily neutral and uncritical. Therefore, it cannot be a reliable prediction tool and can only be called a “tireless shadow writer” (Dehouche, 2021). Thus, when students rely too much on AI to create or learn and never check or question the content generated, their learning focus will shift from relying on self-learning for innovation to “training AI.” Then, let AI innovate on their behalf, which will ultimately erode their thinking abilities.

Society and AI: The Flaws of Algorithmic Recognition

AI algorithms have been widely used in all aspects of life, and this technology has undoubtedly improved some people’s lives. For a long time, disability associations and the disabled community have been making efforts for their well-being, and they hope that advanced technology can help the disabled community alleviate the harm caused by diseases or other reasons (Whittaker, 2019). Take the application of artificial intelligence algorithms in self-driving cars as an example. For disabled people with limited mobility, traveling has become extremely difficult. Therefore, self-driving cars powered by AI algorithms can benefit disabled people, effectively improving expensive transportation costs and inconvenient issues.

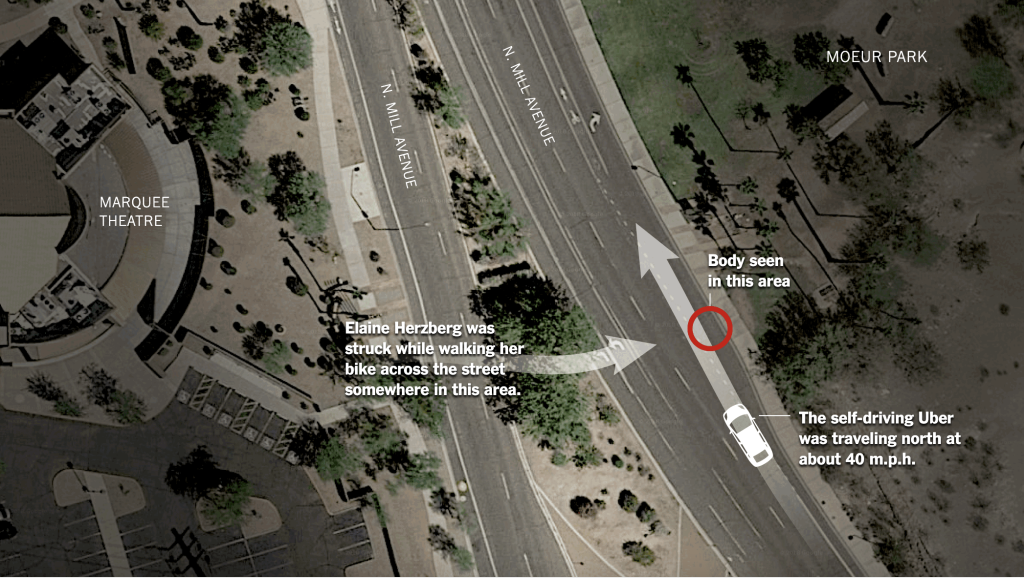

However, technology that could benefit people with disabilities may cause a bigger problem. If the knowledge of training algorithms does not include identifying “other people who use wheelchairs or bicycles to travel,” then they will most likely not be recognized as “pedestrians” (Templeton, 2020). At the same time, when people place too much trust in the solutions brought about by algorithms, it will disrupt their ability to think for themselves, leading to more significant accidents and impacts. In 2018, a woman crossed the street on her bicycle and was killed by a self-driving Uber car. During the police investigation, the police found a driver in the car who seemed distracted at the time of the accident. He did not even put his hands on the steering wheel, stared at the ground with distracted eyes, and appeared to trust algorithms greatly (Griggs & Wakabayashi, 2018).

The scene where the accident occurred (Griggs & Wakabayashi, 2018)

In addition to self-driving cars, people traveling with bicycles and wheelchairs are often run over by “human drivers” who fail to notice them, which means that flaws in the algorithms are not only due to data limitations and lack of training, but also to the fact that the trainer sometimes fails to correctly identify these pedestrians (Templeton, 2020), which confirms that the capabilities of AI are still not entirely reliable. However, people who trust AI algorithms tend to rely on the solutions given by the AI and ignore the importance of self-reflection and critical thinking. After the accident, people may also not feel guilty about what happened to the victim, will only blame the cause of the accident on the error of the algorithm’s operation, and will define it as a low-probability event.

Humans cannot define moral standards for AI because it involves the cultivation of other emotions, such as anger, empathy, and sadness, which stem from human consciousness and cognition. In contrast, AI is not self-aware (Ferrer et al., 2021). Therefore, AI can only partially replace human decision-making or thinking. Taking traffic accidents as another example, when a human driving a car sees a person in a wheelchair slowly crossing an uncontrolled road, most people would choose to slow down or stop too politely. However, the algorithm, not being empathetic, may choose to avoid the emergency after a fast-moving vehicle, causing panic or more severe consequences for the parties involved.

The Challenge of AI’s Governance

Opacity and unpredictability:

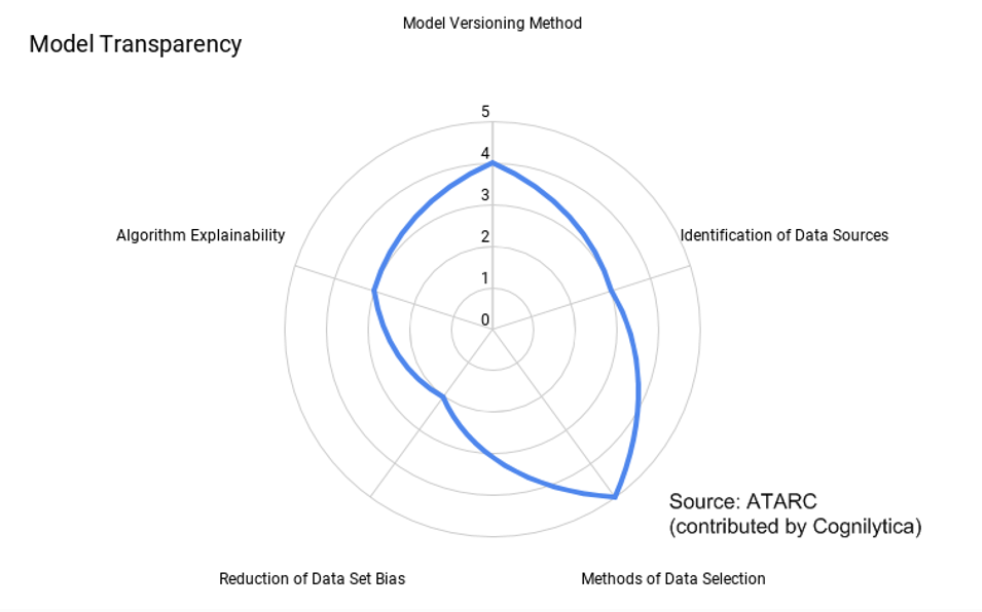

Multi-factor transparency assessment chart” (Schmelzer, 2020)

Keeping algorithms transparent has always been crucial to governance, such as openly scrutinizing algorithms’ design and development process, clearly labeling the sources of data, providing reasonable explanations to users in response to decisions, etc. However, algorithm developers sometimes intentionally keep the algorithms’ data opaque to prevent data leakage triggered by cyberattacks on the system (Carabantes, 2020; Kroll et al., 2016). In addition, most people lack sufficient technical knowledge and are more willing to pay for a quick response, as well as trusting the expertise of AI to help them explain the problem. Therefore, although regulations such as data protection regulations require algorithms to provide explanations of data and decision-making processes, this explanation is not clear and is not enough for the public to understand the principles (Carabantes, 2020).

In addition, since any algorithm decision is derived from the data, any slight input change will affect the final output result, so developers and users cannot fully control the algorithm’s behavior. These decisions made by the algorithm are also unpredictable ( Kroll et al., 2016 ). As a result, the harm caused by software flaws becomes apparent over time, and improving unsafe or discriminatory narratives in algorithms becomes extremely difficult.

Lag in government regulation:

Due to a lack of government understanding of AI technology, thus the regulation has lagged the development of AI. At present, technology companies such as Apple and Google have potent resources and technical information that are sufficient to manage platforms or develop artificial intelligence tools, which have considerably replaced the government’s role in social resource allocation and management (Guihot et al., 2017). Therefore, the inequality between tech companies and governments has led to a slow understanding of AI technology. This results in the government’s inability to promulgate new regulations based on new technologies, and some laws need to be more specific and clear.

As described above, stakeholders in the industry currently have the most cutting-edge development technology, which means that they are deeply involved in and define the standards and regulations for AI algorithms. Raises concerns about the safety of the algorithms, both for people and governments (Hemphill, 2016). This is because people cannot guarantee that in the future, tech companies and politicians in developing AI will thus have more rights and influence. Then, they create new interests and relationships that exacerbate social problems. This allows relevant departments to completely lose control of regulations while exacerbating social problems, such as inequality in social status, rising unemployment, and others. Therefore, the problems caused by regulation have gradually evolved into a significant challenge in the field of artificial intelligence governance.

Thoughts for the Future

In the future, AI will be applied to more areas and have a more significant impact on society. Therefore, it is essential for people nowadays to discover more problems with AI and to manage and improve the potential risks.

Firstly, the government should strengthen its investment in new technologies and explore more related technical talents to ensure the development of science and technology. After that, it should improve management and introduce relevant laws to restrain the control of platforms over algorithms. In addition, since algorithms serve the public, the government can use seminars and other methods to regularly discuss issues with the public or stakeholders, such as algorithm transparency, conduct appropriate science popularization, and collect data from users while alleviating the phenomenon of “over-reliance” preferences, making the application of AI more transparent and democratic.

In response to fraudulent behavior in schools, platforms should limit the number of times students can use AI to answer questions and reduce the amount of content available for generation. In addition, platforms need to collaborate with schools and clearly publish usage rules. When fraud is discovered, the platform has the right to suspend all activities of the relevant account temporarily. Schools should encourage students to monitor academic integrity issues and anonymously report potential fraud, thereby reducing the possibility of plagiarism.

After that, technology developers need to optimize the flaws in the algorithm, consider different types of people during development, openly communicate risks with users, and ensure the experience and fairness of the algorithm.

In the end, the governance of AI algorithms will be a long and complex process. For humans, the battle with technology has just begun.

Reference:

Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 228-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press.

Carabantes, M. (2020). Black-box artificial intelligence: An epistemological and critical analysis. AI & Society, 35, 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-019-00888-w

Dehouche, N. (2021). Plagiarism in the age of massive generative pre-trained transformers (GPT-3). Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 21(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00195

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Polity Press.

Ferrer, X., van Nuenen, T., Such, J. M., Coté, M., & Criado, N. (2021). Bias and Discrimination in AI: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 40(2), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1109/MTS.2021.3056293

Green, B. (2021). The Flaws of Policies Requiring Human Oversight of Government Algorithms (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3921216). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3921216

Griggs, T., & Wakabayashi, D. (2018, March 21). How a Self-Driving Uber Killed a Pedestrian in Arizona. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/20/us/self-driving-uber-pedestrian-killed.html

Guihot, M., Matthew, A. F., & Suzor, N. P. (2017). Nudging robots: Innovative solutions to regulate artificial intelligence. Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, 20, 385.

Hemphill, T. A. (2016). Regulating nanomaterials: A case for hybrid governance. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 36(4), 219–228.

Kroll, J. A., Barocas, S., Felten, E. W., Reidenberg, J. R., Robinson, D. G., & Yu, H. (2016). Accountable algorithms. U. Pa. L. Rev, 165, 633.

Nolan, B. (2023, January 14). Two professors who say they caught students cheating on essays with ChatGPT explain why AI plagiarism can be hard to prove. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/chatgpt-essays-college-cheating-professors-caught-students-ai-plagiarism-2023-1

Templeton, B. (2020, August 5). Self-Driving Cars Can Be A Boon For Those With Disabilities. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bradtempleton/2020/08/05/self-driving-cars-can-be-a-boon-for-those-with-disabilities/?sh=6ca09a814017

Whittaker, M., Crawford, K., Dobbe, R., Fried, G., Kaziunas, E., Mathur, V., Schwartz, O. (2019). Disability, bias, and AI. AI Now Institute.

Be the first to comment