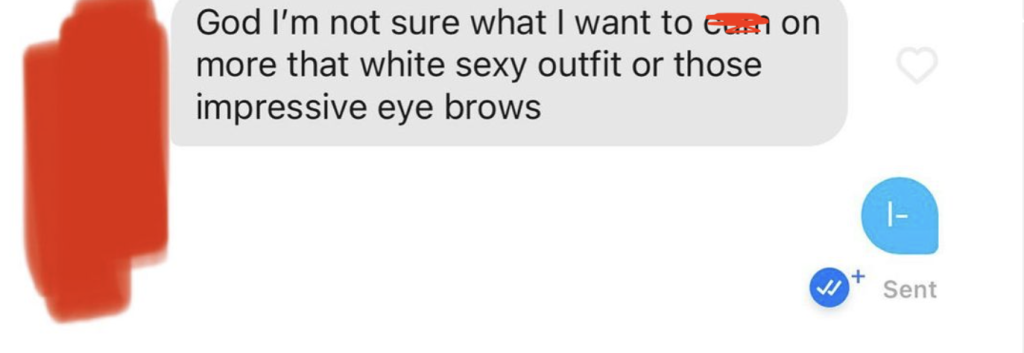

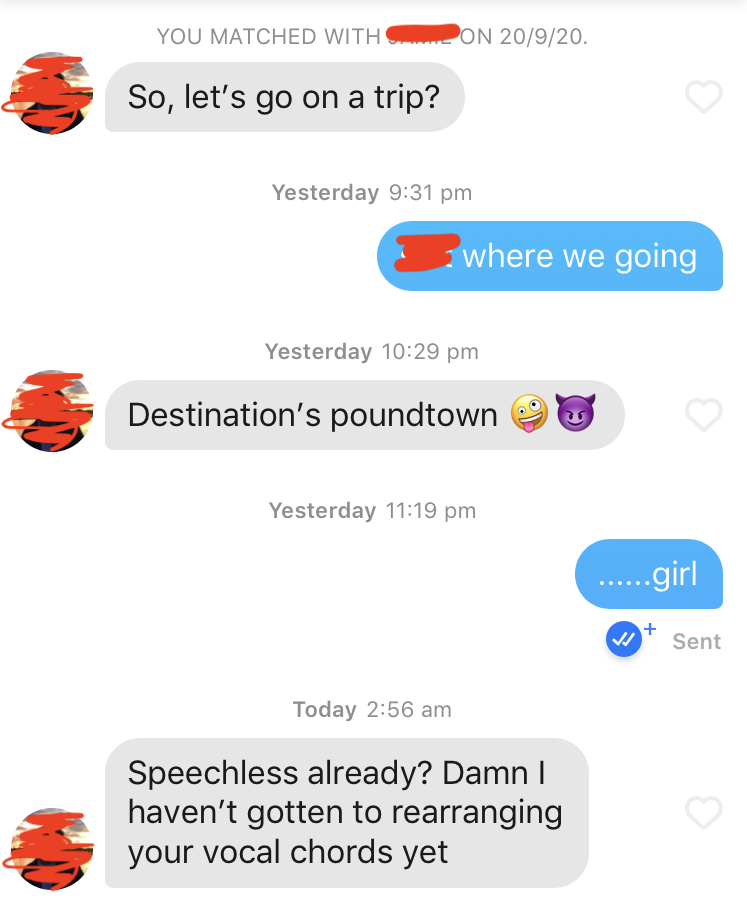

Young women will probably recognise the following scenario: a female friend shows you a screenshot from a dating app. An anonymous man has sent her an unsolicited dick pic, made jokes about raping her on a date, or opened a conversation by asking her “How’s that p***y” (in some extra-special scenarios, it may have a combination of all three!). This man won’t be aware, or won’t care, that he’s done anything wrong. You and your friends laugh, call him a creep, laugh, wonder who raised him to be that way, laugh some more. We find it so funny that we make Instagram pages solely dedicated to laughing at misogynists on dating apps. Why are we laughing?

As much as feminist rhetoric seems to be coming into the mainstream, the fact is that patriarchal societies are sustained by the normalisation of misogyny (Cama, 2021, pg. 334). Nowhere is this more apparent than on social media and dating apps, which have allowed misogynistic discourses, communities and figures to gain social and cultural power through hands-off, passive approaches to content regulation (Massanari, 2016). Dating apps like Tinder provide the ultimate observation deck for how young men perpetuate rape culture and misogyny – and yet, the men who use misogynistic hate speech rarely face tangible consequences for their actions. Sure, women can use the safety features on the app and block men, report men, and complain about men. But chances are, they’ll be back on the app after a three-day ban, or they won’t experience any consequences at all.

This lack of accountability is at the centre of the growing normalisation of misogynistic hate speech, oppressive speech and sexual violence on dating apps. As dating apps like Tinder lack robust frameworks to protect women and are not held directly responsible for the behaviour of their users (Flew, 2021, pg. 85), men can escape accountability for the psychological, emotional and physical harm they cause women through misogynistic hate speech.

Misogynistic Hate Speech and Sexual Violence in the Digital World

We can’t understand hate speech against women without understanding how it manifests online, as it thrives within an online culture that implicitly and explicitly normalises misogyny and violence against women. Flew (2021, pg. 95) defines hate speech as “[stigmatising] the target group by implicitly or explicitly ascribing to it qualities widely regarded as highly undesirable”, through which “the target group is viewed as an undesirable presence and a legitimate object of hostility”.

I would argue that when we talk about misogynistic hate speech online, this definition has to be broadened to include sexually violent and oppressive language, which is far more normalised than physical sexual violence (Gillett, 2023, pg. 204). Forms of online sexual violence against women such as “non-consensual sexting and pornography or online sexual harassment” (Thompson, 2018 pg. 73) ultimately serve the same purpose as hate speech: they cause women psychological harm which is just as tangible as that caused by offline sexual violence, and remind women of their subordinate social position (Richardson-Self, 2017, pg. 264). This hate speech is particularly prevalent on dating apps. For example, a survey of Australian women found that 57% of participants had experienced sexual harassment on a dating app in the last year (Cama, 2021, pg. 335). But considering how ubiquitous misogyny is in women’s lives, many more women may experience sexual harassment and misogyny on dating apps without even registering it as such (Gillet, 2023, pg. 201).

Dating apps also don’t exist in a vacuum – men who engage in misogynistic hate speech are encouraged by the broader context of online rape culture, which refers to a “complex set of beliefs that encourages male sexual aggression and supports violence against women”. Within this culture, “sexual violence against women is implicitly and explicitly condoned, excused, tolerated, and normalized” (Cama, 2021, pg. 336). It seems only natural that within this context, men would expect that they would face little to no consequences for sexually harassing and abusing women online.

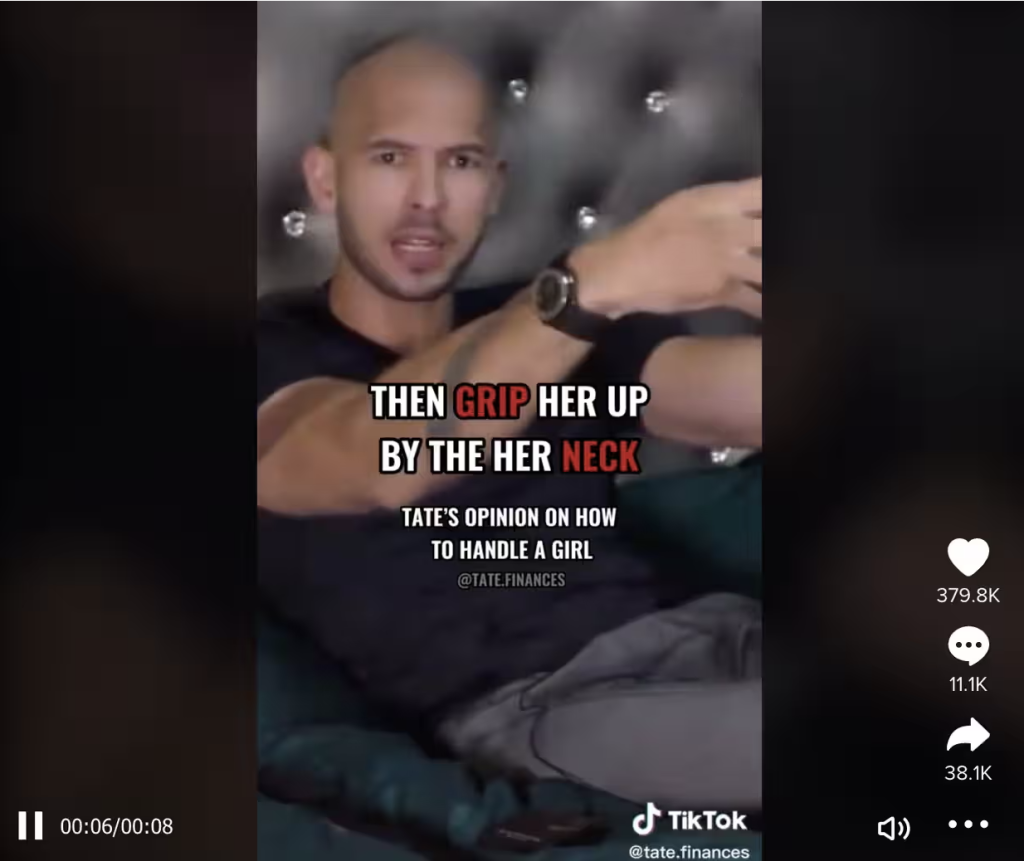

And unfortunately, they would usually be right. Rape culture was able to thrive online in the first place, largely because of the hands-off approach many online platforms take to moderating the behaviour of their users (Flew, 2021, pg. 85). How else would figures like Andrew Tate, who was indicted for rape and human trafficking and said that rape victims have to “bear responsibility” for their attacks, be allowed to become so influential? Figures like Tate may get banned from TikTok or X for a little while, but they always come back, and keep their platform to spread misogynistic rhetoric to (mostly young) men globally. We see the same cycle happening with users of dating apps like Tinder.

Tinder

Tinder exemplifies how user regulation (or a lack thereof) on dating apps enables misogynistic hate speech. Tinder is one of the most popular and profitable dating apps, with 57 million users worldwide (Cama, 2021, pg. 334). It is also widely considered a ‘hookup app’, an image that Tinder has previously played into in its advertising campaigns. As Tinder has become characterised as a hookup app, many Tinder users perceive having a Tinder profile as prioritising casual, detached sexual experiences over meaningful romantic connections (Thompson, 2018, pg. 72). This deliberately disinterested, superficial, apathetic face of Tinder naturally engenders misogynistic hate speech, so much so that social media pages like Tinder Nightmares have been created to satirise and call out misogyny on Tinder specifically.

Clearly, an app that gets so much flak for its misogynistic and sometimes hostile users isn’t doing enough to protect its users from abuse and harassment. The regulatory measures designed to minimise experiences of abuse and harassment on Tinder mostly manifest as safety features that users activate. This includes measures like blocking and unmatching, which Tinder recommends for stopping unwanted communication (Cama, 2021, pg. 341). While blocking will stop communication with an unwanted user, it also deletes evidence of conversations, allowing perpetrators to use the block function to delete evidence and escape consequences for their bad behaviour.

The Tinder Safety and Policy website also outlines their policy for reporting users who violate community guidelines, which can encompass “harassment, threats, bullying, intimidation, doxing, sextortion, blackmail, or anything intentionally done to cause harm”. When a user reports somebody they’ve matched with for any of these reasons, Tinder’s website claims that their team “takes appropriate measures, which may include removing the content, banning the user, or notifying the appropriate law enforcement resources”.

In theory, the reporting feature is an effective way to weed out misogynists on Tinder. But the reality is disappointing, to say the least. Banning, for example, is one of the most common measures employed against users who have been reported for violating community guidelines. However, these bans usually only last a few days, after which offenders will be allowed back on the app without further consequences. Alternatively, when faced with a longer ban, users will face no issues making a new account under a new name or email address (Cama, 2021, pg. 340). Even worse, an investigation by the ABC revealed that Tinder often fails to respond to users who report abusive behaviour altogether, even when the abuse extends to physical harm suffered on Tinder dates, like rape and physical assault.

This is not to say that women should not report instances of abuse, harassment and misogyny, or that Tinder’s safety features are always ineffective. But just as women are less likely to report physical harassment and sexual violence to authorities, women who are victims of misogynistic hate speech are fairly unlikely to report perpetrators. Frankly, it’s understandable that they wouldn’t. Female Tinder users who date men are not blind to the inadequacy of Tinder’s safety features – just as they aren’t blind to the ineffectiveness of police and other authorities in investigating sexual assault and harassment. But as men have been allowed to continue to harass female Tinder users, misogyny has become almost synonymous with women’s usage of dating apps, so women have come to consider misogyny, harassment and hate speech on dating apps “unpleasant but ordinary, expected, and normalised” (Gillett, 2023, pg. 204).

Dating Apps Evade Responsibility as Women Suffer

Tinder isn’t the only dating app, or even the only communication platform, that uses the ineffectiveness of its regulatory frameworks to avoid responsibility for the behaviour of its users. This avoidance of responsibility is characteristic of digital communication platforms, which rest in some sort of legal limbo where they “enjoy all the right to intervene, but with little responsibility about how they do so and under what forms of oversight” (Gillespie, 2018, pg. 272).

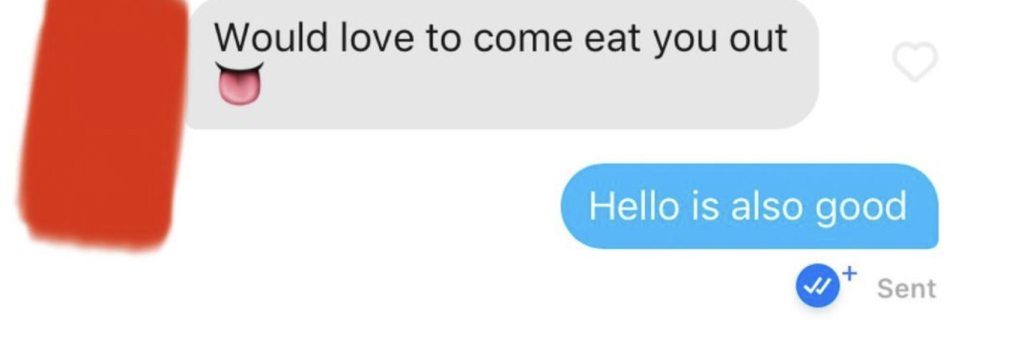

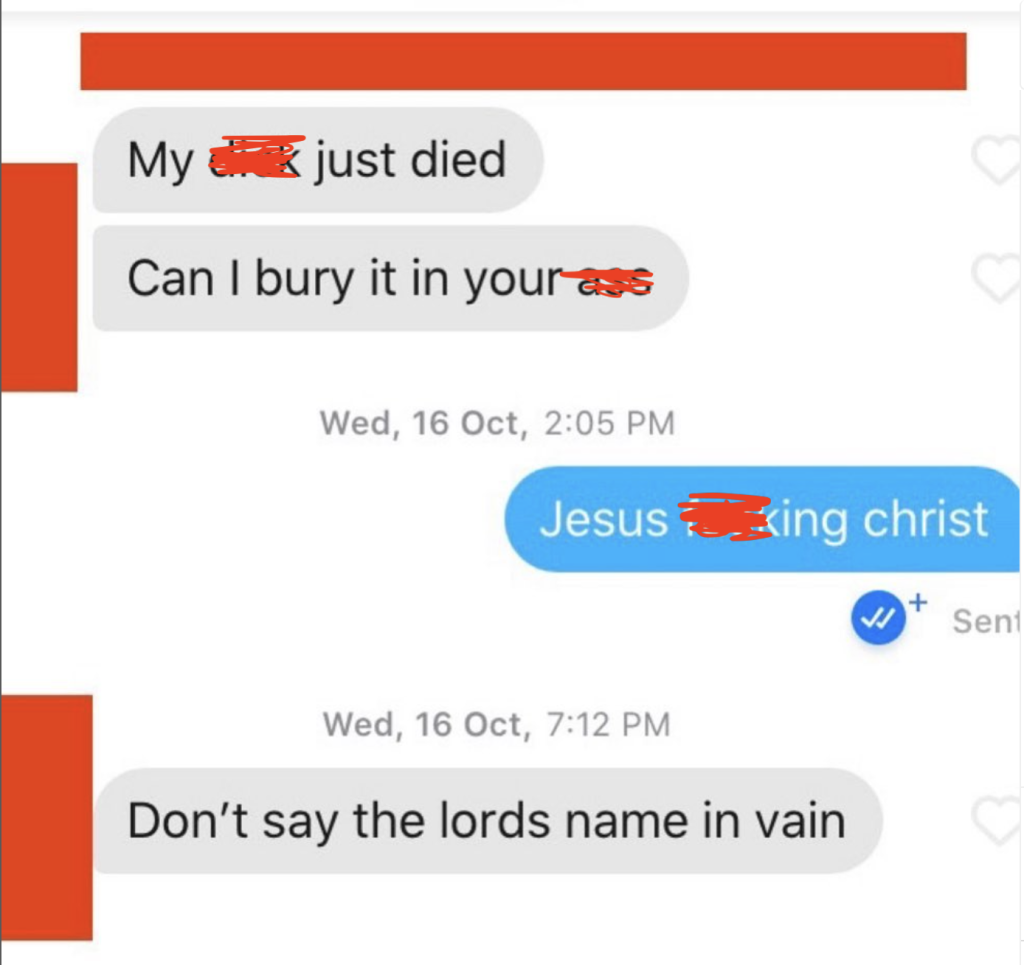

Indeed, platforms can’t be held entirely responsible for how their users behave – in the case of dating apps, the sickness of abuse and harassment against women goes far deeper than issues with safety features. But dating apps also can’t entirely defer responsibility for the spread of misogynistic abuse on their platforms to individual offenders, especially not after it’s become so inextricably linked with the experience of using dating apps. As mentioned earlier, misogynistic hate speech has become so deeply embedded in online spaces that many women use dating apps with the expectation that they will either see or experience misogyny (Cama, 2021, pg. 339). During my brief stint on Tinder, I was one of these women, until one opening message sent me over the edge:

I know you’re wondering how I could resist such a tempting offer, from such a prize of a man. But that was it! I deleted Tinder and my other dating apps, surrendering to the knowledge that I could either use these apps and accept a certain amount of misogynistic abuse, or remove myself from the modern dating scene.

Many women who date men are faced with a similar choice – and if they choose to stay on the apps, they are forced to do their own “safety work” to limit their exposure to sexual violence, abuse and interactions that make them feel “uneasy, uncomfortable or unsafe” (Gillett, 2023, pg. 199). The practices of reporting, blocking, and unmatching profiles, and of vetting the profiles of prospective matches for ‘red’ and ‘green’ flags, are repeated so much that they become habitual, and are “absorbed into the body as a kind of hidden labour” (Gillett, 2023, pg. 201). So women become instruments of the normalisation of their own oppression, forced to constantly regulate, witness and fear sexual violence and abuse (Flew, 2021, pg. 93), while dating apps intervene as minimally as possible.

Unfortunately, mitigating the spread of misogyny on dating apps isn’t as simple as improving safety features. The regulation of misogynistic rhetoric online can only come with the regulation of communication platforms more broadly – which isn’t exactly within the financial or operational interests of platforms, who enjoy minimal governance beyond the regulations and parameters they set for themselves (Gillespie, 2018, pg. 271).

A popular argument against the regulation of communication platforms is that it would undermine free speech and the way the internet was initially conceived; as a utopian, libertarian space where all were free to share their opinions and thoughts without fear of censorship (Flew, 2021, pg. 2). This objection does present an interesting, somewhat valid question to consider when thinking about the regulation of social media and other platforms, a question which I can’t provide a definitive answer to. However, I will say that the people who conceived of the internet in this way were largely straight, white, cisgender men – in other words, the Western world’s only demographic that cannot suffer from hate speech in any meaningful, life-altering way.

Maybe in some version of the future, dating apps and other communication platforms will be held more accountable for the actions of their users. But to limit misogynistic hate speech online, this will have to happen alongside so many other societal shifts; rape culture will have to be diffused in popular discourses, powerful executives in charge of platforms will have to accept accountability for the functions of their platforms, men will have to face consequences for their misogynistic transgressions within and beyond the online sphere. And as a woman who has: laughed along with friends showing screenshots of horrific misogyny, much worse than what was included in this article; who has tired of doing her own safety work; and who sometimes has to deliberately stop herself from thinking about the hate speech suffered by women online to keep from coming to the conclusion that men just hate her and her kind – I can’t see it happening any time soon.

Sources

Andrew Tate to be extradited to UK over rape and human trafficking allegations. (2024, March 13). SBS News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/andrew-tate-to-be-extradited-to-uk-over-rape-and-human-trafficking-allegations/2dpsr9uog

Bonos, L. (2018, December 13). Analysis | Tinder and OkCupid have given up on finding you a soul mate. Their ads even admit it. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2018/12/13/tinder-okcupid-have-given-up-finding-you-soul-mate-their-ads-even-admit-it/

Coma, E. (2021). Understanding Experiences of Sexual Harms Facilitated through Dating and Hook Up Apps among Women and Girls. In J. Bailey, A. Flynn, & N. Henry (Eds.), The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse (pp. 333–350). Emerald Publishing Ltd.

Community Guidelines. (n.d.). Tinder. Retrieved March 30, 2024, from https://policies.tinder.com/community-guidelines/intl/en/?lang=en-AU

Das, S. (2022a, August 6). How TikTok bombards young men with misogynistic videos. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/revealed-how-tiktok-bombards-young-men-with-misogynistic-videos-andrew-tate

Das, S. (2022b, August 6). Inside the violent, misogynistic world of tiktok’s new star, Andrew Tate. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/aug/06/andrew-tate-violent-misogynistic-world-of-tiktok-new-star

Dias, A., McCormack, A., & Russell, A. (2020, October 12). “Predators can roam”: How Tinder is turning a blind eye to sexual assault. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-12/tinder-dating-app-helps-sexual-predators-hide-four-corners/12722732?nw=0

Flew, T. (2021a). Algorithms. In Regulating Platforms (pp. 82–86). Polity.

Flew, T. (2021b). Issues of Concern: Hate Speech. In Regulating Platforms (pp. 91–96). Polity.

Flew, T. (2021c). The End of the Libertarian Internet. In Regulating Platforms (pp. 1–41). Polity.

Gale, E. (2018). Tinder Nightmares . Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/tindernightmares/?hl=en

Gillespie, T. (2018). Regulation Of and By Platforms. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 255–278). SAGE Publications, Limited.

Gillett, R. (2021). “This is not a nice safe space”: investigating women’s safety work on Tinder. Feminist Media Studies, 23(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1948884

Massanari, A. (2016). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Richardson-Self, L. (2018). Woman-Hating: On Misogyny, Sexism, and Hate Speech. Hypatia, 33(2), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12398

Safety And Policy. (n.d.). Tinder Policy Centre. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://policies.tinder.com/safety-and-policy/intl/en/

Suzor, N., & Gillett, R. (2020, October 13). Tinder fails to protect women from abuse. But when we brush off “dick pics” as a laugh, so do we. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/tinder-fails-to-protect-women-from-abuse-but-when-we-brush-off-dick-pics-as-a-laugh-so-do-we-147909

Thompson, L. (2018). “I can be your Tinder nightmare”: Harassment and misogyny in the online sexual marketplace. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517720226

Tweten, A. (n.d.). Bye Felipe . Instagram. Retrieved March 30, 2024, from https://www.instagram.com/byefelipe/?hl=en

Be the first to comment